Rodeo Cowgirls : an Ambivalent Arena

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alvin Youth Livestock & Arena Association

Alvin Youth Livestock & Arena Association Cultivating the Youth of today into Champions of tomorrow Post Office Box 1596 832-250-2688 Alvin, Texas 77512 www.aylaarodeo.org Summer Series Rules 1. CONTESTANT ELIGIBILITY 1.1 Contestant or contestant’s parent/legal guardian, or immediate family must be a current AYLAA MEMBER to be eligible to compete in the AYLAA Summer Series. If you are the guardian of a child, proof of guardianship must be provided. Immediate family is defined by residing in the same household and/or a legal dependent. Lifetime members’ children are only eligible to use their parents’ lifetime membership until the age of 19. Grandchildren are not considered immediate family. o Annual membership fees are $35.00 per family, per year; beginning June 1 and ending May 31. Lifetime membership fees are $200. Organization/Corporate membership fees are $400. o A NON-MEMBER may purchase an entry PERMIT for $10 per week. The non-member will not receive points. If the non-member places in an event, the points for that place will be dropped and given to AYLAA members up to 10 places. 1.2 A copy of the child’s BIRTH CERTIFICATE must be turned in at the time of registration. This includes all previous members. 1.3 Participant must be 19 YEARS OF AGE OR YOUNGER, determined as of September 1 of the previous year. 1.4 A notarized MINOR’S RELEASE signed by at least one parent or legal guardian prior to participating in any event will be required. A legal guardian must have proof of guardianship 1.5 Contestants may NOT be MARRIED. -

78Th Annual Comanche Rodeo Kicks Off June 7 and 8

www.thecomanchechief.com The Comanche Chief Thursday, June 6, 2019 Page 1C 778th8th AAnnualnnual CComancheomanche RRodeoodeo Comanche Rodeo in town this weekend Sponsored The 78th Annual Comanche Rodeo kicks off June 7 and 8. The rodeo is a UPRA and CPRA sanctioned event By and is being sponsored by TexasBank and the Comanche Roping Club Both nights the gates open at 6:00 p.m. with the mutton bustin’ for the youth beginning at 7:00 p.m. Tickets are $10 for adults and $5 for ages 6 to 12. Under 5 is free. Tickets may be purchased a online at PayPal.Me/ ComancheRopingClub, in the memo box specify your ticket purchase and they will check you at the gate. Tickets will be available at the gate as well. Friday and Saturday their will be a special performance at 8:00 p.m. by the Ladies Ranch Bronc Tour provided by the Texas Bronc Riders Association. After the rodeo on both nights a dance will be featured starting at 10:00 p.m. with live music. On Friday the Clint Allen Janisch Band will be performing and on Saturday the live music will be provided by Creed Fisher. On Saturday at 10:30 a.m. a rodeo parade will be held in downtown Comanche. After the parade stick around in downtown Comanche for ice cream, roping, stick horse races, vendor booths and food trucks. The parade and events following the parade are sponsored by the Comanche Chamber of Commerce. Look for the decorated windows and bunting around town. There is window decorating contest all over town that the businesses are participating in. -

For the Love of the Ride You Love to Ride

www.americanvaulting.org 1 For the Love of the Ride You love to ride. Everyday if it’s possible. They do, too. Their legs carry you through training, or hours on the trail. So check their legs daily, treat early and reverse joint damage to keep on riding. Rely on the proven treatment. Go to www.FortheLoveoftheRide.com and tell us about your love of the ride. Every Stride Counts “Official Joint Therapy” of USDF and “Official Joint Therapy” of USEF There are no known contraindications to the use of intramuscular Adequan® i.m. brand Polysulfated Glycosaminoglycan in horses. Studies have not been conducted to establish safety in breeding horses. WARNING: Do not use in horses intended for human consumption. Not for use in humans. Keep this and all medications out of the reach of children. Caution: Federal law restricts this drug to use by or on the order of a licensed veterinarian. Each 5 mL contains 500 mg Polysulfated Glycosaminoglycan. Brief Summary Indications: For the intramuscular treatment of non-infectious degenerative and/or traumatic joint dysfunction and associated lameness of the carpal and hock joints in horses. SEE PRODUCT PACKAGE INSERT FOR FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION. Adequan® is a registered trademark of Luitpold Pharmaceuticals, Inc. ©LUITPOLD PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., Animal Health Division, Shirley, NY 11967.AHD 9560-6, lss. 3/10 EVM 2 EquEstrianVaultinG | Summer 2010 EquEstrian VaultinG COlumNs 5 From the President Sheri Benjamin 6 16 11 Coaching Corner Standing Out Nancy Stevens-Brown 14 Horse Smarts On Quiet, Supple, and Obedient: Frequently Asked Questions Yossi Martonovich 18 Just for Vaulters Core is More! Megan Benjamin and Stacey Burnett 25 Through the Eyes of the Judges 22 28 The Ins and Outs of Composition Suzanne Detol Features 6 Men's Vaulting: The Extreme Equestrian Sport Sheri Benjamin HcertiorseMansFiedHiP For the Love of the Ride 10 AVA Recognizes Life and Longtime Members You love to ride. -

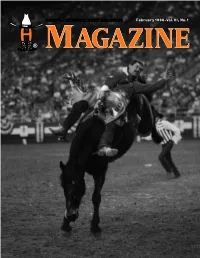

BHM 1998 Feb.Pdf

TTABLEABLE OFOF CONTENTSCONTENTS MAGAZINE COMMITTEE A Message From the President.......................................................... 1 Features OFFICER IN CHARGE The Show’s New Footprint ........................................................ 2 J. Grover Kelley CHAIRMAN Blue Ribbon Judges ..................................................................... 4 Bill Booher Impact of Pay-Per-View — Now and in the Future ................... 6 VICE CHAIRMAN Taking Stock of Our Proud Past ............................................... 8 Bill Bludworth EDITORIAL BOARD 1998 Attractions & Events.......................................................... 10 Suzanne Epps C.F. Kendall Drum Runners.............................................................................. 12 Teresa Lippert Volunteer the RITE Way............................................................... 14 Peter A. Ruman Marshall R. Smith III Meet Scholar #1.................................................................... 15 Constance White Committee Spotlights COPY EDITOR Larry Levy International .................................................................................. 16 REPORTERS School Art ...................................................................................... 17 Nancy Burch Gina Covell World’s Championship Bar-B-Que ....................................... 18 John Crapitto Sue Cruver Show News and Updates Syndy Arnold Davis PowerVision Steps Proudly Toward the Future.......................... 19 Cheryl Dorsett Freeman Gregory Third-Year -

Hallie Hanssen & Ux Kimmitted Ta Fame Lock up $29,089 at Classic

JANUARY 10, 2017 Volume 11: Issue 2 In this issue... • Classic Equine Futurity, pg 18 • No Bull, Jacksonville, FL, pg 29 • CO vs. The World, Denver, CO, pg 37 fast horses, fast news • Fame Fling N Bling, pg 42 Published Weekly Online at www.BarrelRacingReport.com - Since 2007 Hall & Dreaming Of Foose Sweep Isabella Quarter Horses Futurity & Ultimate Texas Barrel Classic Slot Futurity By Tanya Randall Dreaming Of Foose (“Cali”) has come a long way from an ORONA ARTEL unbroke, unraced 2-year-old and started 3-year-old that garnered no TEL ORONA C C S C SI 96 interest as a potential futurity contender to a $26,000 champion. SI 105 The 4-year-old brown mare and her owner and trainer Sharin Hall OUR LI P S A RE SEALE D of Oklahoma City topped both the Isabella Quarter Horses Futu- FOOSE rity and Ultimate Texas Barrel Classic Slot Futurity in Edna, Texas, SI 102 ROYAL QUICK DASH Jan. 5-8. The slot race victory was worth $15,000, while the futurity SU mm ERTI M E QUICKIE SI 101 win paid $9,592 in the $30,000-added event. SI 94 “I bought her sight-unseen off of Barrel Horse World,” laughed SU mm ERTI M E HIGH Hall. “I bought her off a picture—her conformation first and DREA M ING OF FOOSE SI 84 papers second. I told myself that I wanted something so fast that if 2013 BAY FILLY I made mistake she was still going to clock, and that’s what I got.” FIRST DOWN DASH After purchasing the unbroke 2-year-old by AQHA Racing Cham- SI 105 pion Foose out of Hawks Dream Girl, by Hawkinson, from her HAWKINSON breeders Childers Ranch, LLC, of Templeton, Calif., Hall couldn’t SI 99 OH LA PROU D find the filly a ride to Oklahoma. -

Special Buyers Guide Pullout

M A Y – J U N E 2 0 1 5 SPECIAL BUYERS The Magazine GUIDE of Rural Telco PULLOUT Management What One Video Streaming Service Has Meant for Rural Telecom Providers, Consumers and the Programs They Watch 20 Homegrown Tech Incubators 24 Local and Lovin’ It 28 RTIME Wraps Up in Phoenix RTMay-June2015.FINAL_cc.indd 1 4/27/15 3:37 PM Communications Technology Media Success in today’s fluid telecom environment requires an experienced partner with laser focus and the GVNW ability to execute communication, technology and media strategies that AD result in sustainable growth. PAGE 2 With offices throughout the country and over 4 decades of experience, the GVNW team has the knowledge, resources and expertise to develop growth strategies, improve operations and maximize the organizational effectiveness for your company. RTMay-June2015.FINAL_cc.indd 2 4/27/15 3:08 PM Communications Technology Media Success in today’s fluid telecom environment requires an experienced partner with laser focus and the FINLEY ability to execute communication, technology and media strategies that AD result in sustainable growth. PAGE 3 With offices throughout the country and over 4 decades of experience, the GVNW team has the knowledge, resources and expertise to develop growth strategies, improve operations and maximize the organizational effectiveness for your company. RTMay-June2015.FINAL_cc.indd 3 4/27/15 3:08 PM In Every Issue 6 FROM THE TOP 8 SHORT TAKES 10 #RURALISSOCIAL 12 CONNECTIONS Your Telecom Information Hub By Shirley Bloomfield 14 PERSPECTIVE Targeted Message -

Friday, May 29, 2020 6:30 P.M

FRIDAY, MAY 29, 2020 6:30 P.M. | STEPHENS CO. EXPO CENTER | DUNCAN, OKLAHOMA 6:30 P.M. ON FRIDAY, MAY 29, 2020 STEPHENS CO. EXPO CENTER DUNCAN, OKLAHOMA Welcome to the 2020 Bred to Buck Sale, With all the changes going on in the world, one thing that remains the same is our focus of producing elite bucking bulls. For over 35 years, we have strived to produce the very best in the business. We know the competition gets better every year so we work to remain a leader in the industry. One thing we have proven is all the great bulls are backed by proven cow families. Our program takes great pride in our cows and we KNOW they are the key to our operation. We sell 200 plus females each year between the Fall Female Sale and this Bred to Buck Female Sale, so we have our cow herd fine-tuned to only the most proven cow families. It is extremely hard to select females for this sale knowing that many of our very best cows will be leaving the program. However, we do take pride in the success our customers have with the Page genetics. There are so many great success stories from our customers, and we can’t begin to tell them all. Johna Page Bland, Office 2020 is a year we will never forget, our country has experienced changes and regulations that we have never seen throughout history. We will get through this, but we will have to 580.504.4723 // Fax: 580.223.4145 make some adjustments along the way. -

===GAME GAB • WEEK THREE LINER NOTES CONTENTS • Pete

===== GAME GAB • WEEK THREE LINER NOTES CONTENTS • Pete Adams/Rob Gallamore, bull riding (revised) • James Cast, bull riding (revised) • Rob Gallamore, tie-down roping (new) • Elan Oliff, steer wrestling (new) ===== DESIGNER NOTES/EMAIL JAMES CAST Keith and Sam, Thanks for last night's show. That was fun. I got a lot of good feedback from Keith and also picked up some ideas from the others who participated. I have streamlined my game considerably! I also converted the cards and charts to PDF to make it easier to share. I like the progress to date and looking forward to getting some play testing done with it. Feel free to share it with others, and they can also have my email address. Now ... I wanted to get this over quickly, because I have an idea for the whole rodeo concept. It's based on the Wrestling card game Book It! You start with a stable of local cowboys and in the course of several events you try to amass enough reputation points to be a top rodeo promoter. Cards would include cowboy cards, venue cards, and special event cards (i see this where you would include chuckwagon, cowboy poker, and other special events to boost reputation). I haven't thought through most of the conceptual pieces yet, but in essence it's a deck building game (right up Sam's alley). ===== ROB GALLAMORE Here you go Keith, this is what my Tie Down Roping Game looks like. I exported it to a pdf this time. I bought Affinity Publisher about a week ago as it was half price. -

215269798.Pdf

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

The Following Event Descriptions Are Presented for Your Edification and Clarification on What Is Being Represented and Celebrated in Bronze for Our Champions

The following event descriptions are presented for your edification and clarification on what is being represented and celebrated in bronze for our champions. RODEO: Saddle Bronc Riding Saddle Bronc has been a part of the Calgary Stampede since 1912. Style, grace and rhythm define rodeo’s “classic” event. Saddle Bronc riding is a true test of balance. It has been compared to competing on a balance beam, except the “apparatus” in rodeo is a bucking bronc. A saddle bronc rider uses a rein attached to the horse’s halter to help maintain his seat and balance. The length of rein a rider takes will vary on the bucking style of the horse he is riding – too short a rein and the cowboy can get pulled down over the horse’s head. Of a possible 100 points, half of the points are awarded to the cowboy for his ride and spurring action. The other half of the points come from how the bronc bucks and its athletic ability. The spurring motion begins with the cowboy’s feet over the points of the bronc’s shoulders and as the horse bucks, the rider draws his feet back to the “cantle’, or back of the saddle in an arc, then he snaps his feet back to the horse’s shoulders just before the animal’s front feet hit the ground again. Bareback Riding Bareback has also been a part of the Stampede since 1912. In this event, the cowboy holds onto a leather rigging with a snug custom fit handhold that is cinched with a single girth around the horse – during a particularly exciting bareback ride, a rider can feel as if he’s being pulled through a tornado. -

Shorty's Yarns: Western Stories and Poems of Bruce Kiskaddon

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2004 Shorty's Yarns: Western Stories and Poems of Bruce Kiskaddon Bruce Kiskaddon Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the Folklore Commons Recommended Citation Kiskaddon, B., Field, K., & Siems, B. (2004). Shorty's yarns: Western stories and poems of Bruce Kiskaddon. Logan: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHORTY’S YARNS Western Stories and Poems of Bruce Kiskaddon Illustrations by Katherine Field Edited and with an introduction by Bill Siems Shorty’s Yarns THE LONG HORN SPEAKS The old long horn looked at the prize winning steer And grumbled, “What sort of a thing is this here? He ain’t got no laigs and his body is big, I sort of suspicion he’s crossed with a pig. Now, me! I can run, I can gore, I can kick, But that feller’s too clumsy for all them tricks. They’re breedin’ sech critters and callin’ ‘em Steers! Why the horns that he’s got ain’t as long as my ears. I cain’t figger what he’d have done in my day. They wouldn’t have stuffed me with grain and with hay; Nor have polished my horns and have fixed up my hoofs, And slept me on beddin’ in under the roofs Who’d have curried his hide and have fuzzed up his tail? Not none of them riders that drove the long trail. -

Trunk Contents

Trunk Contents Hands-on Items Bandana – Bandanas, also known as "snot rags," came in either silk or cotton, with the silk being preferred. Silk was cool in the summer and warm in the winter and was perfect to strain water from a creek or river stirred up by cattle. Cowboys favored bandanas that were colorful as well as practical. With all the dust from the cattle, especially if you rode in the rear of the herd (drag), a bandana was a necessity. Shirt - The drover always carried an extra shirt, as 3,000 head of cattle kicked up a considerable amount of dust. The drovers wanted a clean shirt available on the off- chance that the cowboy would be sent to a settlement (few and far between) to secure additional supplies. Crossing rivers would get your clothes wet and cowboys would need a clean and dry shirt to wear. Many times they just went into the river without shirt and pants. For superstitious reasons many cowboys did not favor red shirts. Cuffs - Cuffs protected the cowboy's wrist from rope burns and his shirt from becoming frayed on the ends. Many cuffs were highly decorated to reflect the individual's taste. Students may try on these cuffs. 1 Trunk Contents Long underwear – Cowboys sometimes called these one-piece suits "long handles." They wore long underwear in summer and winter and often kept them on while crossing a deep river, which gave them a measure of modesty. Long underwear also provided extra warmth. People usually wore white or red "Union Suits" in the West.