United Nations Security Council Reform | 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Variable Multipolarity and U.N. Security Council Reform

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLI\53-2\HLI202.txt unknown Seq: 1 22-MAY-12 12:26 Volume 53, Number 2, Summer 2012 Variable Multipolarity and U.N. Security Council Reform Bart M.J. Szewczyk Table of Contents Introduction .............................................. 451 R I. Identifying the Security Council’s Problem ....... 452 R A. Conventional Critiques and Reforms ................... 455 R B. Misdiagnoses of the Council’s Power ................... 458 R C. Misdiagnoses of the Council’s Legitimacy................ 462 R D. Theoretical Limitations of Existing Reforms ............. 466 R II. Interpreting the Security Council’s Purpose ...... 471 R A. Text, Context, and Practice of Article 24 ............... 472 R B. Uncertainty of Law and Power in Complex Orders ....... 475 R C. Empirical Analysis of Legitimacy ..................... 480 R D. Norms of Legitimacy ................................ 483 R III. Inclusive Contextual Cooperation in the United Nations ............................................. 488 R A. Development of Shared Understandings ................. 488 R B. Expected Future Scenarios of the World ................. 495 R C. Reforms for the Security Council....................... 497 R D. Reforms for the General Assembly ..................... 499 R IV. Conclusion ......................................... 500 R \\jciprod01\productn\H\HLI\53-2\HLI202.txt unknown Seq: 2 22-MAY-12 12:26 450 Harvard International Law Journal / Vol. 53 Variable Multipolarity and U.N. Security Council Reform Bart M.J. Szewczyk* One of the fundamental international law questions over the past two decades has been the structure of the United Nations Security Council. In a world of variable multipolarity, whereby changing crises demand different combinations of actors with relevant resources and shared interests, the Council’s reform should be based not on expanded permanent membership—as mistakenly held by conventional wisdom—but on inclusive contextual participation in decisionmaking. -

Security Council Reform STUDENT OFFICER: Cate Goldwater-Breheney POSITION: Assistant Chair

FORUM: Security Council ISSUE: Security Council Reform STUDENT OFFICER: Cate Goldwater-Breheney POSITION: Assistant Chair Introduction What is the UNSC and how does it work? The United Nations Security Council is an organ of the United Nations with “primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security”. Its powers include the establishment of international sanctions and peacekeeping operations, as well as the authorization of military action and investigation of conflicts. It is the only UN body that can issue binding resolutions to other member states – in other words, you have to do what it says. Furthermore, it deals with the admittance of new UN member states and Secretary-General (UN “leader”) candidacies. It is thus a very powerful body within the UN, and has been involved in serious international issues, including the Korean War, the Suez Canal Crisis and more recently the Rwandan Genocide. The UNSC has a complicated set-up. It has 15 members, five of whom are permanent members: France, the UK, the USA, China and Russia (essentially the victors from WW2). These permanent members have veto powers; should they vote against a resolution, it automatically does not pass. Resolutions otherwise require a 2/3 majority to pass, or 10 votes in favour. The 10 non-permanent members are elected for two year terms on a regional basis; the African Group holds 3 seats, the Latin America and the Caribbean, Asia-Pacific, and Western European and Others groups, 2 seats, and the Eastern European group, 1 seat. The presidency of the UNSC rotates monthly. UNSC non-permanent members in 2019 are: Germany, Belgium, South Africa, the Dominican Republic, Indonesia, the Ivory Coast, Equatorial Guinea, Kuwait, Peru, and Poland. -

Responsibility to Protect Or Reform?

12 April 2012 Responsibility to Protect or Reform? The doctrine of Responsibility to Protect is not going to disappear soon — and neither is the question of UN Security Council Reform. As time passes, they are becoming more and more intertwined. But which should take precedent? By Casey L. Coombs for ISN UN Security Council (UNSC) resolution 1973 -- the legal basis for NATO’s six month bombing campaign to enforce a no-fly zone in Libya -- was the first unambiguous use of the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) doctrine. R2P is an emerging international humanitarian and security norm which grants the Council power to intervene if a sovereign state is unable, or unwilling, to protect its population from war crimes, genocide, ethnic cleansing or other crimes against humanity. In 2005, all 191 member states in the UN General Assembly (GA) endorsed the doctrine in principle. After the experiences of the Libyan intervention however, UN members are now torn over how or even if R2P can be fairly implemented in practice. The debate has crippled the UNSC on Syria and according to former UN Assistant Secretary-General Ramesh Thakur, rekindled serious concerns about the need to reform the 15-nation body to bring it into the twenty-first century. The Controversy The NATO air campaign over Libya was a qualified success. Successful in that it fulfilled its R2P obligations of averting what appeared at the time to be the almost certain slaughter of hundreds of thousands of Benghazians at the hand of Colonel Muammar Qaddafi’s army; qualified, however, because NATO went beyond just protecting anti-Qaddafi rebels by supplying them with arms (in contravention of the arms embargo imposed on Libya in resolution 1973) and then actively facilitating the rebels’ eventual takeover of Tripoli. -

Zero Asia Growth for First Time in 60 Yrs?

BHUBANESWAR l FRIDAY l APRIL 17, 2020 l `7.00 l PAGES 12 l LATE CITY EDITION DON’T COLLECT FEES, AICTE WAIT TILL THE END OF LOCKDOWN FULL REFUND FOR CANCELLED FLIGHTS After noting that some institutions are demanding fees from students ■ The Centre on Thursday told airlines to issue full refund for the TELLS ENGINEERING COLLEGES during the lockdown, the AICTE in an advisory said, institutions approved tickets booked during the first phase of the lockdown (March 3-week by it must not insist on the payment of fees till the restrictions are lifted. 25-April 14) for trips in the second phase from April 15 The technical education regulatory body has also told Also, they must withdraw all terminations made during the lockdown. ■ Airlines have so far avoided offering full refunds, extending TIME TO ISSUE FULL REFUND AFTER A institutions not to lay off staff or stop payments of salaries The advisory notes that online classes for current semesters will continue credit vouchers instead. The decision will benefit thousands REQUEST IS MADE BY TRAVELLER CHENNAI ■ MADURAI ■ VIJAYAWADA ■ BENGALURU ■ KOCHI ■ HYDERABAD ■ VISAKHAPATNAM ■ COIMBATORE ■ KOZHIKODE ■ THIRUVANANTHAPURAM ■ BELAGAVI ■ BHUBANESWAR ■ SHIVAMOGGA ■ MANGALURU ■ TIRUPATI ■ TIRUCHY ■ TIRUNELVELI ■ SAMBALPUR ■ HUBBALLI ■ DHARMAPURI ■ KOTTAYAM ■ KANNUR ■ VILLUPURAM ■ KOLLAM ■ WARANGAL ■ TADEPALLIGUDEM ■ NAGAPATTINAM ■ THRISSUR ■ KALABURAGI COMMUNITY SURVEILLANCE Zero Asia growth for first time in 60 yrs? ODISHA TO START Lockdown to burn a `12 lakh crore hole on India’s economy, says SBI Research; FM meets PM to chalk out strategy RANDOM TESTS EXPRESS NEWS SERVICE planned policy responses to it. and use capital controls to bat- @ Hyderabad / New Delhi HISTORIC The Covid-19 crisis is Meanwhile, IMF expects a tle any disruptive capital out- expected to inflict steep declines 7.6% expansion in Asian eco- flows it noted. -

Critical Currents No.4 May 2008

critical currents Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation Occasional Paper Series The Quest for Regional Representation Reforming the United Nations Security Council no.4 May 2008 Beyond Diplomacy – Perspectives on Dag Hammarskjöld 1 critical currents no.4 May 2008 The Quest for Regional Representation Reforming the United Nations Security Council Edited by Volker Weyel With contributions by Richard Hartwig Kaire M. Mbuende Céline Nahory James Paul Volker Weyel Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation Uppsala 2008 The Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation pays tribute to the memory of the second Secretary-General of the UN by searching for and examining workable alternatives for a socially and economically just, ecologically sustainable, peaceful and secure world. In the spirit of Dag Hammarskjöld's integrity, his readiness to challenge the Critical Currents is an dominant powers and his passionate plea Occasional Paper Series for the sovereignty of small nations and published by the their right to shape their own destiny, the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation. Foundation seeks to examine mainstream It is also available online at understanding of development and bring to www.dhf.uu.se. the debate alternative perspectives of often unheard voices. Statements of fact or opinion are those of the authors and By making possible the meeting of minds, do not imply endorsement experiences and perspectives through the by the Foundation. organising of seminars and dialogues, Manuscripts for review the Foundation plays a catalysing role should be sent to in the identifi cation of new issues and [email protected]. the formulation of new concepts, policy proposals, strategies and work plans towards Series editor: Henning Melber solutions. The Foundation seeks to be at the Language editor: Wendy Davies cutting edge of the debates on development, Design & Production: Mattias Lasson security and environment, thereby Printed by X-O Graf Tryckeri AB continuously embarking on new themes ISSN 1654-4250 in close collaboration with a wide and Copyright on the text is with the constantly expanding international network. -

Elect the Council Concept Note

Elect the Council Motivation and Proposals Version 4 Towards a legitimate and effective UN Security Council At a time of unprecedented global insecurity and turmoil the world needs a legitimate and effective United Nations Security Council (UNSC). There is little prospect of progress towards this goal in the intergovernmental negotiations in New York that is charged with this process. Elect the Council invites comments on this fourth revised version of its proposals for reform of the UNSC. A final document will be the basis for a global mobilization and advocacy campaign. That campaign will work with civil society partners and academics to advocate for an enabling resolution by two thirds of the member states of the UN General Assembly (UNGA). Elect the Council proposes to do away with permanent seats on the UNSC and the veto and to move towards a system where countries are elected to the Council bound to four technical requirements for candidacy. In addition, global powers that exceed a set proportion of the world’s population, economy and defence expenditure will automatically qualify for seats. As a result, after a 15-year transition the UNSC will consist of 24 elected countries plus the two or three countries that will expectedly automatically qualify due to their size and influence. Eight of the 24 elected countries will be elected for five-year terms and will be immediately re-electable. The remaining 16 countries will be elected for three years but not be re- electable. The current five electoral regions that elect the ten non-permanent members of the UNSC will nominate candidates for election by simple majority in the UNGA in line with current practice although changes to the composition of the regions should be pursued. -

Download Brochure

Celebrating UNESCO Chair for 17 Human Rights, Democracy, Peace & Tolerance Years of Academic Excellence World Peace Centre (Alandi) Pune, India India's First School to Create Future Polical Leaders ELECTORAL Politics to FUNCTIONAL Politics We Make Common Man, Panchayat to Parliament 'a Leader' ! Political Leadership begins here... -Rahul V. Karad Your Pathway to a Great Career in Politics ! Two-Year MASTER'S PROGRAM IN POLITICAL LEADERSHIP AND GOVERNMENT MPG Batch-17 (2021-23) UGC Approved Under The Aegis of mitsog.org I mitwpu.edu.in Seed Thought MIT School of Government (MIT-SOG) is dedicated to impart leadership training to the youth of India, desirous of making a CONTENTS career in politics and government. The School has the clear § Message by President, MIT World Peace University . 2 objective of creating a pool of ethical, spirited, committed and § Message by Principal Advisor and Chairman, Academic Advisory Board . 3 trained political leadership for the country by taking the § A Humble Tribute to 1st Chairman & Mentor, MIT-SOG . 4 aspirants through a program designed methodically. This § Message by Initiator . 5 exposes them to various governmental, political, social and § Messages by Vice-Chancellor and Advisor, MIT-WPU . 6 democratic processes, and infuses in them a sense of national § Messages by Academic Advisor and Associate Director, MIT-SOG . 7 pride, democratic values and leadership qualities. § Members of Academic Advisory Board MIT-SOG . 8 § Political Opportunities for Youth (Political Leadership diagram). 9 Rahul V. Karad § About MIT World Peace University . 10 Initiator, MIT-SOG § About MIT School of Government. 11 § Ladder of Leadership in Democracy . 13 § Why MIT School of Government. -

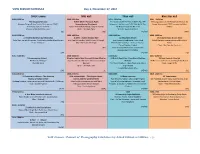

VOW SESSION SCHEDULE Day 1, November 17, 2017

VOW SESSION SCHEDULE Day 1, November 17, 2017 ONGC Lawns SREI Hall Titan Hall Blue Star Hall 1000-1130 hrs 1200-1315 hrs 1215 - 1315 hrs 1245 -1300 hrs The Inaugural Session 7.With Malice Towards None: 11.Launch of the RST Forum by PD Rai, MP 16.Inauguration of the Philately exhibition by Naveen Chopra,Robin Gupta,CS,Governor,CPMG, Remembering Khushwant Release of the Book on Dr RS Tolia by SK Das, Suneel Advani and CPMG curated by Abhai Gurcharan Das,H.P.Kanoria Harish Trivedi/Rahul Singh/ /Syeda Hamid NS Naplachayal and BK Joshi Mishra Release of the First Day cover Chair : Sir Mark Tully Tributes by Well Wishers (SC) (RG) (PT/KR) (RNR) 1140-1250 hrs 1500-1600 hrs 1340-1500 hrs 1300-1400 hrs 1. Hindi Ka Vartman Aur Bhavishya 8.1971 : India's Decisive War 12.Mountain Echoes 17.Victoria Cross: A Love Story Rahul Dev, Suresh Rituparna, Alok Mehta,Baldev Bhai Sharma Maj Gen AJS Sandhu, VSM/Lt Gen TS Shergil, The Changing Landscape : Anup Shah Ashali Verma in conversation with Col DPK Chair : LS Bajpai Maj Gen Shamsher Singh The Decadal Journeys - Askot to Arakot : Pillay Pahar/Shekhar Pathak Chair : Maj Gen Ian Cardozo (AS) State of Indian Mountains: Sustainable Development /IMI/SDFU (DP) (PT/KR) (AS) 1315 -1400 hrs 1330 -1430 hrs 1500-1545 1415-1500 hrs 2.Remembering Shivani 9.Indira: India’s Most Powerful Prime Minister 13.Asia ki Peeth Par : Uma Bhatt/Shekhar 18.Book Launch : One Life IRA Pande ,LS Bajpai Sagarika Ghose with Satish Sharma and Anjali Pathak) PK Basu in conversation with Nagendra Kumar Chair:BK Joshi Nauriyal The Pundit Brothers –Nain Singh and Kishen Chair : Swpn Dutta Chair : Sir Mark Tully Singh Rawat Curated by Lokesh Ohri (DP) SC (PT/KR) (SC) 1410-1515 hrs 1615-1715 hrs 1600-1645 1515 -1615 hrs 3. -

Reforming Multilateralism in Post-Covid Times

ited for A NEW MULTILATERALISM EDITED BY MARIO TELÒ REFORMING MULTILATERALISM IN POST-COVID TIMES FOR A MORE REGIONALISED, BINDING AND LEGITIMATE UNITED NATIONS EDITED BY Mario Telò REFORMING MULTILATERALISM IN POST-COVID TIMES IN POST-COVID REFORMING MULTILATERALISM PUBLISHED IN DECEMBER 2020 BY Foundation for European Progressive Studies Avenue des Arts 46 B-1000 Brussels, Belgium +32 2 234 69 00 [email protected] www.feps-europe.eu @FEPS_Europe EDITOR AND PROJECT SCIENTIFIC DIRECTOR Mario Telò LEADER OF THE PROJECT Maria João Rodrigues, President, Foundation for European Progressive Studies FEPS COORDINATORS OF THE PROJECT Hedwig Giusto, Susanne Pfeil IAI COORDINATOR OF THE PROJECT Ettore Greco COPYRIGHT © 2020 Foundation for European Progressive Studies (FEPS) PROOFREADING AND COPY EDITING Nicky Robinson GRAPHIC DESIGN Triptyque.be COVER PHOTO Shutterstock PRINTED BY Oficyna Wydawnicza ASPRA-JR Published with the financial support of the European Parliament. The views expressed in this report are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Parliament. ISBN 978-2-930769-46-2 PROJECT PARTNERS FRIEDRICH-EBERT-STIFTUNG NEW YORK OFFICE 747 Third Avenue, Suite 34D, New York, NY 10017, United States +1 (212) 687-0208 [email protected] https://www.feps-europe.eu @fesnewyork FONDATION JEAN-JAURÈS 12 Cité Malesherbes, 75009 Paris, France +33 (0)1 40 23 24 00 https://jean-jaures.org [email protected] @j_jaures CENTRO STUDI DI POLITICA INTERNAZIONALE (CeSPI) Piazza Venezia 11, 00187 Roma, Italy +39 -

The United Nations Security Council

Working Paper Series W-2019/2 The United Nations Security Council: History, Current Composition, and Reform Proposals Madeleine O. Hosli Thomas Dörfler www.cris.unu.edu About the authors: Madeleine O. Hosli, Director UNU-CRIS and Professor of International Relations at Leiden University, [email protected]. Thomas Dörfler, Research Fellow at the Chair for International Organizations and Policies at the University of Potsdam, [email protected]. 2 3 Abstract The paper explores how the Security Council has reacted to the changing global order in terms of institutional reform and its working methods. First, we look at how the Security Council’s setup looks increasingly anachronistic against the tremendous shifts in global power. Yet, established and rising powers are not disengaging. In contrast, they are turning to the Council to address growing challenges posed by the changing nature of armed conflict, the surge of terrorism and foreign fighters, nuclear proliferation and persistent intra-state conflicts. Then, we explore institutional and political hurdles for Council reform. While various reform models have been suggested, none of them gained the necessary global support. Instead, we demonstrate how the Council has increased the representation of emerging powers in informal ways. Potential candidates for permanent seats and their regional counterparts are committed as elected members, peacekeeping contributors or within the Peacebuilding Commission. Finally, we analyze how innovatively the Council has reacted to global security challenges. This includes working methods reform, expansion of sanctions regimes and involvement of non-state actors. We conclude that even though the Council’s membership has not yet been altered, it has reacted to the changing global order in ways previously unaccounted for. -

GNP Or GNH: How Realistic Is the Choice? B.K

hi adri 4 D O O N L I B R A R Y June, 2010 & R e s e a r c h C e n t r e GNP or GNH: How realistic is the choice? B.K. Joshi n a recent issue of the Nepali programmes within the nationally and procedures. Unfortunately, it ITimes1, Artha Beed2 has written determined framework. remains a fact that the notion of a thought-provoking column titled GNH as distinguished from GNP is “Himalayan experiments: Can Bhutan The choice, however, is not an easy nowhere on the horizon of possible get it right?” Based on his recent visit one. It would, in fact, mean turning options in India today. No political to Bhutan he says: “The Bhutanese our back on many of the conveniences party has espoused the idea as talk extensively about Gross National that we now take for granted and evidenced by their manifestoes in Happiness (GNH) as a counter to are becoming increasingly addicted the last parliamentary election; market and consumption driven to. These would doubtless include neither does it figure in academic GDP. For instance, mountaineering in the private car/motor cycle/scooter, debates and discussions. On the Bhutan is not allowed, as it has been internet, cable or dish television and contrary a wide consensus seems to deemed that the mountains should mobile phone to name just a few. exist in the country on the notion of be kept as they are. Their conception Artha Beed poses these questions in inclusive growth. The issue therefore of measuring people's happiness the context of Bhutan in the following is can and should the notion of Gross as opposed to consumption or words: National Happiness become the production is unique, and is a counter “While a small population can allow new orthodoxy in development? Is it to western measures of prosperity.” for Singapore-style governance and desirable? Is it possible? If so how? We feel that this sentiment will control, the opening up of information We are posing this question with find resonance in many people access will be difficult to stem.