UK Gender-Sensitive Parliament Audit Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Speaker 1

THE SPEAKER 1. Election of the Speaker: Member presiding Drafting amendments 1A. Re-election of former Speaker Drafting amendments 1B. Election of Speaker by secret ballot Drafting amendments DEPUTY SPEAKER AND CHAIRMEN 2. Deputy Chairmen Repeal, because superseded by SO No. 2A 2A. Election of the Deputy Speakers Change of timing of ballot to reflect existing practice; rafting amendments; clarifications; additional paragraph to reflect existing practice on appointment of interim Deputy Speakers at start of a Parliament 3 Deputy Speaker Rename ‘Duties and powers of Deputy Speakers’ to reflect substance 4 Panel of Chairs Amendment for flexibility to allow Deputy Speakers to chair legislation committees without formal appointment to committee; merger with SO no. 85 MEMBERS (INTRODUCTION AND SEATING) 5. Affirmation in lieu of oath No change 6. Time for taking the oath No change 7. Seats not to be taken before prayers No change 8. Seats secured at prayers No change SITTINGS OF THE HOUSE 9. Sittings of the House Drafting amendments; deletion of obsolete provisions; new language to stop adjournment debates lapsing at moment of interruption 10. Sittings in Westminster Hall Drafting amendments; updating and rationalisation. 11. Friday sittings Amalgamated with No 12 and No. 14: Drafting amendments; removal of clash with SO No. 154 (Petitions); updating 12. House not to sit on certain Fridays Amalgamated with No 11: Drafting amendments; addition of text from other SOs for clarity; amendment to reflect existing practice 13. Earlier meeting of House -

Pay for Chairs of Committees Final Report May 2016

Pay for Chairs of Committees Final report May 2016 PAY FOR CHAIRS OF COMMITTEES FINAL REPORT MAY 2016 Contents Foreword by the Board of IPSA .................................................................................................. 2 1. Our consultation ................................................................................................................ 3 2. Responses to the consultation and IPSA’s position ........................................................... 4 Chairs of Select Committees .................................................................................... 4 Members of the Panel of Chairs ............................................................................... 7 Future adjustments to salary ................................................................................. 12 3. Implementation ............................................................................................................... 14 Annex A – Determination on the Additional Salary for Specified Committee Chairs ............. 15 Annex B – Salaries for Members of the Panel of Chairs since introduction ........................... 17 Annex C – Salaries for Chairs of Select Committees since introduction ................................. 18 Foreword by the Board of IPSA IPSA has a statutory obligation to conduct a review of MPs’ pay and pensions in the first year of each Parliament. This includes a statutory obligation to review the additional salaries that are paid to Chairs of Select Committees, and to Members of the Panel -

Parallel Chambers

PARALLEL CHAMBERS Memorandum from Sir David Natzler KCB, Clerk of the House of Commons, to The House of Commons (Canada) Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs This memorandum will primarily focus on Westminster Hall, the parallel Chamber in the House of Commons, which has been in operation since 1999. Some reference to the operation of Grand Committees will also be included towards the end of the memorandum. WESTMINSTER HALL Overview 1. During the 1998-99 parliamentary session, the House of Commons Modernisation Committee published two reports regarding proposals for a parallel Chamber. Taking inspiration from procedures used in the House of Representatives, Canberra, where certain business was conducted in a parallel (albeit subordinate) Chamber, the first of these reports indicated some of the issues which would need to be addressed if a parallel Chamber were to be introduced, the impact it might have on the House of Commons, as well as some proposals for how it might work practically. The report was agreed to by the House, and the Committee embarked upon a second report to take the proposals forward. 2. The second of these reports, published later that session, reiterated the arguments for a parallel Chamber and outlined proposals for procedure relating to chairing the sittings, sitting hours, and types of Business to be taken, as well as procedure during the meetings themselves. The Report was approved by the House on 24 May 1999. 3. Since the beginning of the 1999-2000 Session, parallel sittings have been held in Westminster Hall and have provided the House of Commons with an additional forum for debate which has created more parliamentary time without increasing sitting hours. -

Standing Orders

STANDING ORDERS PUBLIC BUSINESS 2019 This volume contains the Standing Orders in force on 6 November 2019 Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 5 November 2019 HC 314 TABLE OF CONTENTS Dates when each standing order was passed and amended xiii The Speaker 1. Election of the Speaker: Member presiding 1 1A. Re-election of former Speaker 1 1B. Election of Speaker by secret ballot 2 Deputy Speakers and Chairmen 2. Deputy Chairmen 5 2A. Election of the Deputy Speakers 5 3. Deputy Speaker 7 4. Panel of Chairs 8 Members (Introduction and Seating) 5. Affirmation in lieu of oath 9 6. Time for taking the oath 9 7. Seats not to be taken before prayers 9 8. Seats secured at prayers 9 Sittings of the House 9. Sittings of the House 9 10. Sittings in Westminster Hall 11 11. Friday sittings 14 12. House not to sit on certain Fridays 15 13. Earlier meeting of House in certain circumstances 16 Arrangement and Timing of Public and Private Business 14. Arrangement of public business 17 15. Exempted business 20 16. Proceedings under an Act or on European Union documents 23 17. Delegated legislation (negative procedure) 23 18. Consideration of draft legislative reform orders etc. 24 ii STANDING ORDERS 19. New writs 26 20. Time for taking private business 26 Questions, Motions, Amendments and Statements 21. Time for taking questions 27 22. Notices of questions, motions and amendments 28 22A. Written statements 29 22B. Notices of questions etc. during September 29 22C. Motions and amendments with a financial consequence for the House of Commons: Administration Estimate 30 22D. -

Addendum to the Standing Orders 2 October 2020

ADDENDUM TO STANDING ORDERS PUBLIC BUSINESS 2 October 2020 Reprinted from the Votes and Proceedings of the House of Commons 16 and 21 January, 3 February, 2, 19 and 24 March, 20 May, 2, 4, 8, 10 and 23 June, 1, 20 and 22 July, 2 and 23 September 2020 AMENDMENTS TO STANDING ORDERS 41A. Deferred divisions 119. European Committees 122B. Election of select committee chairs 143. European Scrutiny Committee 149. Committee on Standards 150. Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards 152K. Public Bodies: draft orders STANDING ORDER DISAPPLIED FOR THE DURATION OF THE 2019 PARLIAMENT 122A. Term limits for chairs of select committees STANDING ORDERS DISAPPLIED UNTIL 3 NOVEMBER 7. Seats not to be taken before prayers 8. Seats secured at prayers 38. Procedure on divisions 40. Division unnecessarily claimed 83J. Certification of bills etc. as relating exclusively to England or England and Wales and being within devolved legislative competence 83K. Committal and recommittal of certified England only bills 83L. Reconsideration of certification before third reading 83M. Consent Motions for certified England only or England and Wales only provisions 83N. Reconsideration of bills so far as there is absence of consent 83O. Consideration of certified motions or amendments relating to Lords Amendments or other messages 83P. Certification of instruments 83Q. Deciding the question on motions relating to certified instruments 83R. Deciding the question on certain other motions 83S. Modification of Standing Orders Nos. 83J to 83N in their application to Finance Bills 83T. Modification of Standing Orders Nos. 83P and 83Q in their application to financial instruments 83U. Certification of motions upon which a Finance Bill is to be brought in which would authorise provision relating exclusively to England, to England and Wales or to England, Wales and Northern Ireland 83V. -

Fitting the Bill: Bringing Commons Legislation Committees Into Line with Best Practice

DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE FITTING THE BILL BRINGING COMMONS LEGISLATION COMMITTEES INTO LINE WITH BEST PRACTICE MEG RUSSELL, BOB MORRIS AND PHIL LARKIN Fitting the Bill: Bringing Commons legislation committees into line with best practice Meg Russell, Bob Morris and Phil Larkin Constitution Unit June 2013 ISBN: 978-1-903903-64-3 Published by The Constitution Unit School of Public Policy UCL (University College London) 29/30 Tavistock Square London WC1H 9QU Tel: 020 7679 4977 Fax: 020 7679 4978 Email: [email protected] Web: www.ucl.ac.uk/constitution-unit/ ©The Constitution Unit, UCL 2013 This report is sold subject to the condition that is shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. First Published June 2013 2 Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................... 4 Executive summary ............................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 7 Part I: The current system .................................................................................................... 9 The Westminster legislative process in -

Standingorders

S T A N D I N G O R D E R S OF THE H O U S E O F C O M M O N S PUBLIC BUSINESS 2013 Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 19 December 2013 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY OF THE HOUSE OF COMMONS LONDON – THE STATIONERY OFFICE £10.00 900 i TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Dates when Standing Orders were passed and amended.................................ix Table showing times of sittings and other events..........................................xix THE SPEAKER 1. Election of the Speaker: Member presiding...........................................1 1A. Re-election of former Speaker ...............................................................1 1B. Election of Speaker by secret ballot.......................................................2 DEPUTY SPEAKER AND CHAIRMEN 2. Deputy Chairmen ...................................................................................5 2A. Election of the Deputy Speakers ............................................................6 3. Deputy Speaker ......................................................................................8 4. Panel of Chairs .......................................................................................9 MEMBERS (INTRODUCTION AND SEATING) 5. Affirmation in lieu of oath .....................................................................9 6. Time for taking the oath.........................................................................9 7. Seats not to be taken before prayers.....................................................10 8. Seats secured at prayers........................................................................10 -

Order Paper for Wed 30 Oct 2019

Wednesday 30 October 2019 Order Paper No.11: Part 1 SUMMARY AGENDA: CHAMBER 11.30am Prayers No debate Motion for an Unopposed Return Afterwards Oral Questions: Northern Ireland 12 noon Oral Questions: Prime Minister 12.30pm Urgent Questions, Ministerial Statements (if any) Until any hour* Business of the House (Today) Motion (*if the 7.00pm Business of the House motion is agreed to) 2 Wednesday 30 October 2019 OP No.11: Part 1 Up to three hours** General Debate: Report from the Grenfell Tower inquiry (**if the Business of the House (Today) motion is agreed to) Until any hour*** Northern Ireland Budget Bill: Business of the House (Motion) (***if the 7.00pm Business of the House motion is agreed to) Up to three hours Northern Ireland after commencement Budget Bill: All Stages of proceedings on the (****if the Northern Northern Ireland Budget Ireland Budget Bill: Bill: Business of the Business of the House House Motion**** Motion is agreed to) No debate Presentation of Public Petitions Wednesday 30 October 2019 OP No.11: Part 1 3 Until 7.30pm or for half Adjournment Debate: an hour Use of accounting systems to facilitate cross-border trade (Luke Graham) WESTMINSTER HALL 9.30am Building out extant planning permissions 11.00am Integrated foreign policy after the UK leaves the EU (The sitting will be suspended from 11.30am to 2.30pm.) 2.30pm Child poverty in Scotland 4.00pm Bus passes for 1950s women 4.30pm The contribution of the Gujarati community to the UK 4 Wednesday 30 October 2019 OP No.11: Part 1 CONTENTS CONTENTS PART 1: BUSINESS TODAY 5 Chamber 23 Westminster Hall 25 Written Statements 27 Committees meeting today 33 Committee reports published today 34 Announcements 39 Further Information PART 2: FUTURE BUSINESS 44 A. -

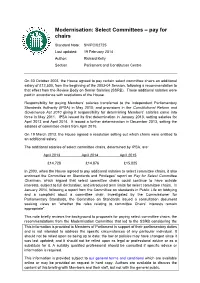

Modernisation: Select Committees – Pay for Chairs

Modernisation: Select Committees – pay for chairs Standard Note: SN/PC/02725 Last updated: 19 February 2014 Author: Richard Kelly Section Parliament and Constitution Centre On 30 October 2003, the House agreed to pay certain select committee chairs an additional salary of £12,500, from the beginning of the 2003-04 Session, following a recommendation to that effect from the Review Body on Senior Salaries (SSRB). These additional salaries were paid in accordance with resolutions of the House. Responsibility for paying Members’ salaries transferred to the Independent Parliamentary Standards Authority (IPSA) in May 2010; and provisions in the Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010 giving it responsibility for determining Members’ salaries came into force in May 2011. IPSA issued its first determination in January 2013, setting salaries for April 2013 and April 2014. It issued a further determination in December 2013, setting the salaries of committee chairs from April 2015. On 19 March 2013, the House agreed a resolution setting out which chairs were entitled to an additional salary. The additional salaries of select committee chairs, determined by IPSA, are: April 2013 April 2014 April 2015 £14,728 £14,876 £15,025 In 2003, when the House agreed to pay additional salaries to select committee chairs, it also endorsed the Committee on Standards and Privileges’ report on Pay for Select Committee Chairmen, which argued that select committee chairs could continue to have outside interests, subject to full declaration; and introduced term limits for select committee chairs. In January 2014, following a report from the Committee on standards in Public Life on lobbying and a complaint about a committee chair, investigated by the Commissioner for Parliamentary Standards, the Committee on Standards issued a consultation document seeking views on “whether the rules relating to committee Chairs’ interests remain appropriate”. -

Feedback on the Customized Training Programme on Parliamentary Administration : European Study Tour at Ripa International, Lond

FEEDBACK ON THE CUSTOMIZED TRAINING PROGRAMME ON PARLIAMENTARY ADMINISTRATION : EUROPEAN STUDY TOUR AT RIPA INTERNATIONAL, LONDON & AT THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION, BRUSSELS, BELGIUM 6TH TO 17TH OCTOBER, 2014 1 I along with 9 other Officers from different Services of the Secretariat was nominated for the fortnight long customized training programme on Parliamentary Administration: European Study Tour at RIPA International, London and at the European Parliament, Brussels, Belgium from the 6th to the 17th of October, 2014. The course consisted of presentations on different topics related to varying aspects of Parliamentary functioning, administration, political landscape, role of media vis-à-vis politicians, Parliament etc. by senior Officers of the U.K. Parliament, experts in the field of parliamentary procedure, practice and administration as well as media persons covering Parliament. The programme was also supplemented by visits to the Houses of Parliament, Supreme Court and the European Parliament and European Commission in Brussels. 2. This learning opportunity was enriching, highly informative, beneficial and fruitful both from the professional and personal point of view. It is said that “the art of teaching is the art of assisting discovery”. RIPA International and the faculties truly put this into practice by their interactive sessions and the entire training programme was a journey of assisted discovery and introspection. The Institute offered excellent training facilities including computer lab, learning atmosphere and support to our team. The extensive use of electronic teaching facilities like e-reader, electronic smart boards etc. made the learning process interesting and facilitated easy retention of the study materials. The faculty and staff at RIPA were very helpful and friendly and were only too eager to satisfy our queries. -

Business of the House and Its Committees

1 Business of the House and its Committees June 2017 Business of the House and its Committees A short guide to the business of the House and its committees – an introduction for new Members Chamber and Committees Team (CCT) Foreword This guide is designed to help Members take part in the business of the House and its committees. There is usually no substitute for face-to-face discussions with the staff responsible for each day-to-day operation. So I would also encourage you to get in touch with the specific office as soon as you decide, or are required, to get involved in a new area of activity. You will be able to identify the office you need via the information in this guide or by visiting the Procedural Hub located next to the Debate cafeteria in the Portcullis House Atrium. And in the first instance, I would encourage you to make direct contact yourself. David Natzler Clerk of the House May 2017 CONTENTS Organisation and Timing of Business 10 Conduct of Business 12 Where To Go For Advice 14 Key Sources of Information 17 Taking part in House and Committee Business: Summary 20 Committee Business 22 As a member of a committee 22 Other opportunities 22 Procedure and Practice 23 Beginning of a new Parliament (chronological): 23 Opening of a new Parliament 23 Swearing in of Members 24 Members’ interests 24 Election of select committee chairs 26 Select committee membership 28 Maiden speeches 28 Day-to-day (A-Z): 29 Adjournment debates 29 Amendments (to motions and bills) 30 Backbench Business Committee 33 Bills – hybrid 34 Bills – private Members’ -

Members' Pay and Expenses and Ministerial Salaries 2016/17

BRIEFING PAPER Number 07762, 10 November 2016 Members' pay and By Richard Kelly expenses and ministerial salaries 2016/17 Contents: 1. Introduction 2. Members’ salaries 3. Members’ expenses 4. Ministers’ salaries www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 Members' pay and expenses and ministerial salaries 2016/17 Contents Summary 4 1. Introduction 6 1.1 The establishment of the Independent Parliamentary Standards Authority (IPSA) 6 1.2 IPSA’s duties 6 1.3 IPSA’s structure 7 2. Members’ salaries 9 2.1 Members’ salaries in the 2015 Parliament 9 2.2 IPSA’s decisions on Members’ pay in the 2010 Parliament 10 Background 10 Initial decisions of IPSA 10 IPSA’s review of Members’ pay 11 2.3 Members’ pay 1997-2016 12 2.4 Additional salaries for select committee chairs and for members of the Panel of Chairs 13 Background 13 House of Commons specifies who qualifies for additional salaries and IPSA determines it 14 IPSA’s March 2016 consultation on additional salaries for committee chairs 15 Select committee chairs 17 Members of the Panel of Chairs 17 3. Members’ expenses 19 3.1 Introduction 19 3.2 Reviews of the MPs’ Expenses Scheme 20 3.3 MPs’ Expenses Scheme Eighth Edition 20 Accommodation Expenditure 21 London Area Living Payment 23 3.4 Travel and Subsistence 24 3.5 Staffing Expenditure 25 Employment of family members 26 3.6 Office Costs Expenditure 28 3.7 Winding-up Expenditure 28 3.8 Loss of Office Payment 29 3.9 Start-up Expenditure 30 3.10 Miscellaneous Expenses 30 3.11 Recall of Parliament 30 3.12 Expenditure during a general election 31 4.