Afrofutures of Cosplay: Deviance and Diy in Black Fantastic Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Please Read These Instructions Carefully Please Return Ballot To

Please Read These Instructions Carefully Please return ballot to: CONZEALAND HUGO ADMINISTRATION c/o TAMMY COXEN 508 LITTLE LAKE DR ANN ARBOR MI 48103 USA This ballot must be received by: Wednesday 15 July 2020 at 11:59pm PDT (GMT-7) Thank you for participating in the 1945 Retrospective Hugo Awards and the 2020 Hugo, Astounding and Lodestar Awards. To vote online, visit the members area on the CoNZealand website and login. Once online voting opens your ballot will be available under “My Memberships.” If you need assistance contact [email protected]. Reproduction Reproduction and distribution of this ballot is permitted and encouraged, provided that it is reproduced verbatim (including voting instructions), with no additional materials other than the name of the person or publication responsible for the reproduction. For more information about the 2020 Hugo Awards and 1945 Retro Hugo Awards, please visit our web page at conzealand.nz/about/explore-worldcon/world-science-fiction-society-about/hugo-awards "World Science Fiction Society", "WSFS", "World Science Fiction Convention", "Worldcon", "NASFiC", "Hugo Award", the Hugo Award Logo, and the distinctive design of the Hugo Award Trophy Rocket are service marks of the World Science Fiction Society, an unincorporated literary society. Eligibility to Vote You may vote for the 2020 Hugo Awards, the Astounding Award for Best New Writer and the Lodestar Award for Best YA Book, and the 1945 Retro Hugo Awards, if you are an Adult Attending or Supporting member of CoNZealand. Please complete the eligibility section, and remember to sign your ballot. How to vote: ● This ballot uses a modified version of the Single Transferable Vote for a single winner, sometimes known as the Alternative Vote or Instant Runoff Ballot. -

May 2016 NASFA Shuttle

Te Shutle May 2016 The Next NASFA Meeting is 6:30P Saturday 21 May 2016 at the Regular Location Concom Meeting 3P at the Church, 21 May 2016 • June: More-or-less Annual NASFA Picnic at Sue’s house. d Oyez, Oyez d This will subsume the meeting, program, and ATMM that ! month. Folks will start gathering at 2P. The next NASFA Meeting will be 21 May 2016, at the regu- • August: Les Johnson will give a talk as well as reading from lar meeting location—the Madison campus of Willowbrook his new book On to the Asteroid <tinyurl.com/OttA-Ama- Baptist Church (old Wilson Lumber Company building) at zon>(co-authored with Travis Taylor). The book will be re- 7105 Highway 72W (aka University Drive). Please see the leased 2 August 2016. map at right if you need help finding it. • October: Con†Stellation Postmortem. MAY PROGRAM The May program will be “Short Attention Span Theater,” featuring short genre and genre-related films gathered from around teh intertubes by Mike Kennedy. Road Jeff Kroger MAY ATMM The May After-The-Meeting Meeting will be hosted by Mary and Doug Lampert at the church. The usual rules apply— US 72W that is, please bring food to share and your favorite drink. Also, (aka University Drive) please stay to help clean up. We need to be good guests and leave things at least as clean as we found them. CONCOM MEETINGS The next Con†Stellation XXXIV Concom Meeting will be Road Slaughter 3P on 21 May 2016—the same day as the club meeting. -

Volume XV Issue 5 Sep-Oct 2016

International Costumer Volume XV, Issue 5 September-October 2016 Safely displaying historic textiles. Courtesy of Vicky Assarattanakul. Researching, Preserving, and Honoring Costume Lady with a rather plain solid dress but her History Rather plain undersleeves visible with belt appears to be the same color, only a pagoda sleeves, Courtesy of Lisa Ashton. shiny fabric with a center buckle. Courtesy of Lisa Ashton. President's Message pipeline of precise call times for actors to be By Philip Gust made up, get into their costumes, go on stage, take off their makeup and costumes, My wife, Kathe, and I just returned from a and leave. There’s simply no room to linger. trip to Laguna Beach, California to see a The Pageant has been running for over 80 performance of the “Pageant of the years, so they’ve had plenty of practice. Masters” https://www.foapom.com/pageant- of-the-masters/ part of the city’s Festival of One of the things that I love about the Arts. The “Pageant of the Masters” is a costuming is the diversity of styles, staged, 90-minute-long show that presents approaches, and uses of materials and over 50 works of art as tableau vivants techniques to create costumes for many (“living pictures”), where actors become purposes. Our visit to the “Pageant of the characters in paintings, sculptures, jeweled Masters” provided an opportunity to brooches, and even crystal perfume bottle explore a unique kind of costuming. But stoppers. while it is done for a very special purpose, it shares with all other kinds of costuming the Over 1000 people volunteer for many pride of the maker and the wearer, and the months to put on the show every night enjoyment of all those who appreciate Philip Gust as “Prof. -

This Newsletter Was Produced by Alison Scott, with Help from Diarmuid Fanning, Jan Van ’T Ent, Flick, Mike, Marianne and Steve

he First Fandom Hall of Note that there is no general access Are you filling your exercise rings? Fame Awards and the Big to the fifth floor foyer; it is reserved Why not take a brisk walk to the Heart were announced at for programme participants, Point, where you will find our the Opening Ceremony. convention staff and volunteers. wonderful Art Show, a fantastic set Remember there is still time to of exhibits, and a range of awesome First Fandom Hall of Fame: Ray volunteer at the desk in the lobby. programme items. Our art auction is Faraday Nelson. silent this year, but our friendly Art First Fandom Posthumous Hall of Show staff will tell you everything Fame: Bob Shaw, James White you need to know through the and Walt Willis. If you have any sort of mobility issue medium of interpretive dance. Sam Moskowitz Archive Award: Dr and you’re attending events in Bradford Lyau. Room 1 Screen 1 at the Odeon, go Big Heart Award: Alice Lawson. to the main Odeon foyer and ask for step free access. Staff will magically If you’re new to Worldcons, you transport you to the area you need might not know that there are to go to. Allow extra time. parties every night that are open to The most beautiful (and funniest) everyone. Here are tonight’s: fanzine ever, Warhoon 28, is now on sale “for the last time” at the DC in 2021 Worldcon—ECOCEM Offworld and Hodges Figgis stalls in When taking photographs of the (next to Wicklow Room 1) 8pm the Forum. -

Cosplay Culture: the Development of Interactive and Living Art Through Play

Ryerson University Digital Commons @ Ryerson Theses and dissertations 1-1-2012 Cosplay Culture: The evelopmeD nt of Interactive and Living Art through Play Ashley Lotecki Ryerson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ryerson.ca/dissertations Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Lotecki, Ashley, "Cosplay Culture: The eD velopment of Interactive and Living Art through Play" (2012). Theses and dissertations. Paper 806. This Major Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Ryerson. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ryerson. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COSPLAY CULTURE: THE DEVELOPMENT OF INTERACTIVE AND LIVING ART THROUGH PLAY by Ashley Lotecki BDes, Fashion Communications, Ryerson University, Canada, 2006 A Major Research Paper presented to Ryerson University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Program of Fashion Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2012 © Ashley Lotecki 2012 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this thesis to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this thesis by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. -

Midamericon II 1941 Retro Hugo Award Finalists

PRESS RELEASE #3 - MIDAMERICON II ANNOUNCES 1941 RETRO HUGO AWARD FINALISTS MidAmeriCon II, the 74th World Science Fiction Convention Kansas City, MO August 17-21, 2016 [email protected] www.midamericon2.org/press FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Tuesday, April 26, 2016 Kansas City, Missouri, USA - the finalists for the 1941 Retro Hugo Awards were announced on Tuesday, April 26, 2016, at 12 Noon CDT. The announcement was made live to social media, including the Twitter and Facebook accounts of MidAmeriCon II, and via the MidAmeriCon II website. 481 valid nominating ballots (475 electronic and 6 paper) were received and counted from the members of the 2015, 2016 and 2017 World Science Fiction Conventions. The final ballot to select this year’s winners will open in mid-May, 2016, and will be open to all Attending, Young Adult, and Supporting members of MidAmeriCon II. The winners of the 1941 Retro Hugo Awards will be announced on Thursday, August 18, in conjunction with the Retro Hugo Swing Dance event. The Hugo Awards are the premier award in the science fiction genre, honoring science fiction literature and media as well as the genre's fans. The Awards were first presented at the 1953 World Science Fiction Convention in Philadelphia (Philcon II), and they have continued to honor science fiction and fantasy notables for well over 60 years. 1941 RETRO HUGO AWARD FINALISTS BEST NOVEL (352 ballots) Gray Lensman by E.E. "Doc" Smith (Astounding Science‐Fiction, Jan 1940) The Ill‐Made Knight by T.H. White (Collins) Kallocain by Karin Boye (Bonnier) The Reign of Wizardry by Jack Williamson (Unknown, Mar 1940) Slan by A.E. -

Mr. Monster 3

ometimes I think Earth has got to be the insane asylum of the universe. and I’m here by computer error. At sixty-eight, I hope I’ve gained some wisdom in the past fourteen lustrums and it’s obligatory to speak plain and true about the conclusions I’ve come to; now that I have been educated to believe by such mentors as Wells, Stapledon, Heinlein, van Vogt, Clarke, Pohl, (S. Fowler) SWright,S Orwell, Taine, Temple, Gernsback, Campbell and other seminal influences in scientifiction, I regret the lack of any female writers but only Radclyffe Hall opened my eyes outside sci-fi. I was a secular humanist before I knew the term. I have not believed in god since childhood’s end. I believe a belief in any deity is adolescent, shameful and dangerous. How would you feel, surrounded by billions of human beings taking Santa Claus, the Easter bunny, the tooth fairy and the stork seriously and capable of shaming, maiming or murdering in their name? I am embarrassed to live in a world retaining any faith in church, prayer or celestial creator. I do not believe in Heaven, Hell or a Hereafter; in angels, demons, ghosts, goblins, the Devil, vampires, ghouls, zombies, witches, warlocks, UFOs or other delusions and in very few mundane individuals - politicians, lawyers, judges, priests, militarists, censors and just plain people. I respect the individual’s right to abortion, suicide and euthanasia. I support birth control. I wish to Good that society were rid of smoking, drinking and drugs. My hope for humanity - and I think sensible science fiction has a -

Mediating Moore: Uncertain Origins and Indeterminate Identities in the Work of C

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) 1-1-2010 Mediating Moore: Uncertain Origins and Indeterminate Identities in the Work of C. L. Moore Jennifer Jodell Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Jodell, Jennifer, "Mediating Moore: Uncertain Origins and Indeterminate Identities in the Work of C. L. Moore" (2010). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 784. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/784 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY University College Liberal Arts MEDIATING MOORE: UNCERTAIN ORIGINS AND INDETERMINATE IDENTITIES IN THE WORK OF C. L. MOORE by Jennifer Lynn Jodell A thesis presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts December 2010 St. Louis, Missouri Acknowledgments I would like to thank my adviser, J. Andrew Brown, and my committee members for their valuable input and guidance. I am also indebted to Stephen Haffner, Richard Bleiler, and the REH society for their referrals to primary source materials, as well as to Carole Ann Rodriguez for her patience in the face of my many questions. Additionally, I am grateful to Judith Hack and Kenneth Polonsky for their moral support and many years of academic inspiration. ii Table of Contents Acknowledgments........................................................................................................................................ -

Sam Moskowitz a Bibliography and Guide

Sam Moskowitz A Bibliography and Guide Compiled by Hal W. Hall Sam Moskowitz A Bibliography and Guide Compiled by Hal W. Hall With the assistance of Alistair Durie Profile by Jon D. Swartz, Ph. D. College Station, TX October 2017 ii Online Edition October 2017 A limited number of contributor's copies were printed and distributed in August 2017. This online edition is the final version, updated with some additional entries, for a total of 1489 items by or about Sam Moskowitz. Copyright © 2017 Halbert W. Hall iii Sam Moskowitz at MidAmericon in 1976. iv Acknowledgements The sketch of Sam Moskowitz on the cover is by Frank R. Paul, and is used with the permission of the Frank R. Paul Estate, William F. Engle, Administrator. The interior photograph of Sam Moskowitz is used with the permission of the photographer, Dave Truesdale. A special "Thank you" for the permission to reproduce the art and photograph in this bibliography. Thanks to Jon D. Swartz, Ph. D. for his profile of Sam Moskowitz. Few bibliographies are created without the help of many hands. In particular, finding or confirming many of the fanzine writings of Moskowitz depended on the gracious assistance of a number of people. The following individuals went above and beyond in providing information: Alistair Durie, for details and scans of over fifty of the most elusive items, and going above and beyond in help and encouragement. Sam McDonald, for a lengthy list of confirmed and possible Moskowitz items, and for copies of rare articles. Christopher M. O'Brien, for over 15 unknown items John Purcell, for connecting me with members of the Corflu set. -

Scientifiction 40 Martino 2014-Sp

SCIENTIFICTION New Series #40 SCIENTIFICTION A publication of FIRST FANDOM, the Dinosaurs of Science Fiction New Series #40, 2nd Quarter 2014 The World Science Fiction Conventiom Father of Science Fiction, the new Free memberships are available for version of the magazine will continue members of the 1939 and 1957 the tradition of publishing both big Worldcons. For more information: names and newcomers to the genre. http://loncon3.org/members_from39a This magazine presentation of Amazing Stories nd57.php. follows its January 2013 return as a multi-author blog The First Fandom Awards will be featuring commentary, reviews, presented on August 14th during the interviews galleries and essays. Retro Hugo Awards Ceremony. Fiction and non-fiction will be Remembering Frederik Pohl published during the month of April with a new story or article appearing “Elizabeth Anne Hull has announced approximately every three days. At that a memorial service will be held the end of the month, the contents on August 2 for family, friends and will be bundled together, formatted fans to celebrate the life and career and offered as an E-zine in a variety of Science Fiction Grand Master of popular formats. If reception of Frederik Pohl (1919–2013), award- the new issue proves to be popular, winning author, editor and fan writer; the publishers contemplate making a influential literary agent; futurist; special print edition available.” lecturer, and member of First Fandom, whose career began in the Necrology Pulp Era and continued until his We are saddened to report the death last year. The free event will recent passing of some friends: Fred be held at the Wojcik Conference D. -

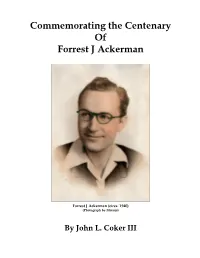

Commemorating the Centenary of Forrest J Ackerman

Commemorating the Centenary Of Forrest J Ackerman Forrest J Ackerman (circa. 1940) (Photograph by Morojo) By John L. Coker III Forrest J Ackerman: Science Fiction Fan No. 1 (An Appreciation by John L. Coker III) In the history of modern science fiction (SF), no person more than Forrest J Ackerman so fully embraced its purpose and gave so much of himself to its fans. From the earliest times, Ackerman was widely regarded as an idealist, someone who embraced an optimistic vision of the future. Forry had an unparalleled enthusiasm for everything related to SF, and became completely immersed in every aspect of the field. Over the course of a lifetime, he assembled a huge collection of artifacts that he made available to everyone. Ackerman will best be remembered for his legendary generosity, and for providing leadership and service to others. Forry was introduced to motion pictures at a young age and he became fascinated with their promise of the future. In 1922, when he was just five and a half years old, his grandparents took him to see his first “imagi-movie” (One Glorious Day). Four years later, he saw Metropolis, the film that was to become his favorite (during his lifetime he watched it over one hundred times). As a youth, Forry regularly went to the movies. He became passionate about the cinema, and eventually developed the ambition to appear in films and view every fantastic movie ever made. AMAZING STORIES Hugo Gernsback Forry’s First Letter October 1926 (Provided by Forry Ackemrnan) (Fall 1929) In October 1926, Ackerman discovered SF in the pages of AMAZING STORIES and he was instantly hooked. -

Fantasy-Fiction

CHICON PROGRAM BOOKLET CHICAGO :: 1940 HOTEL CHICAGOAN SEPTEMBER 1st - 2nd Fantasy Fi&ioneers Joe Gilbert Robert P. Kahn Gerald W. Meader 4sJ Maine Scientifiction Assn. Ron Reynolds Phil Douglas John Heaton Mario Racic, Jr. Gertrude Kuslan Jerry Keeley Louis Kuslan Lew Martin Mirta Forsto Paul Freehafer Henry D. Goldman Morojo George Tullis Hyman Tiger Mary Ellen Tyrrell H. C. Koenig Jean Mehegan Walt Daugherty Lou Sampliner Russ Hodgkins M. Rebeque Eleanor O’Brien Jo Perew Allen Moss Claire Voyant Prof. Gooseberry Bill Crawford Weaver Wright Anton Yoike Beverly Browne Chas. D. Hornig Hoy Ping Pong Jack Williamson Dorothy Sanford Mr. a? Mrs. Sam Korshak Ron Holmes Ray Bradbury John Wasso, Jr. Arthur K. Barnes Pogo Franklyn “Technocrat” Brady Ted Carnell Ivar Towers Georges H. Gallet Chester Cohen Lupe Amador Jack F Speer Chantelle Covington Donald A. Wollheim Tom Wright Adolph Hitler Rajocz Sully Roberds Sophia Van Doorne Benito Mussolini Bruce Yerke Joseph Stalin Ray J Sienkiewicz Jaime Alveras Cardenas Maurice Paul Juan Alpiedio Brazzaro William Sisson Melvin Korshak Vincent Manning R. Royal Marvis Manning Jack Errnan Art Widner, Jr. Bob Madle Joe Fortier Charles Ford Hansen D. B. Thompson Sam Moskowitz Jim Tucker, Jr. Edmond Hamilton Ted Dikty John B. Michel Forrest J Ackerman Cyril Kornbluth Mark Reinsberg Dick Wilson Eva Wolff Braxton Wells Belle Wyman Bob Olsen Erie Korshak Jack Robins Alaska, the Gnome Leslie Perri Allis Kerlay Jack Gillespie Boh Tucker John A. Bristol Erdstelulov Phil Bronson Vodoso Emrys Evans Illini Fantasy Fictioneers Midwest Marky Dirk Wylie Richard I. Meyer Samson Delilah Gottesman THE ILLINI FANTASY FICTIONEERS Sponsors of the CHICON GREET YOU ! Bob TuCkEr, Director Mark REinsbErg, ErLE Korshak, Chairman of the Corresponding Convention Committee Secretary-Treasurer Convention Committee Mark REinsbErg Chairman National Advisory Board Program Advertising Forrest J Ackerman Erie Korshak Robert W.