Contents Old Books

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climatic Variability in Sixteenth-Century Europe and Its Social Dimension: a Synthesis

CLIMATIC VARIABILITY IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY EUROPE AND ITS SOCIAL DIMENSION: A SYNTHESIS CHRISTIAN PFISTER', RUDOLF BRAzDIL2 IInstitute afHistory, University a/Bern, Unitobler, CH-3000 Bern 9, Switzerland 2Department a/Geography, Masaryk University, Kotlar8M 2, CZ-61137 Bmo, Czech Republic Abstract. The introductory paper to this special issue of Climatic Change sununarizes the results of an array of studies dealing with the reconstruction of climatic trends and anomalies in sixteenth century Europe and their impact on the natural and the social world. Areas discussed include glacier expansion in the Alps, the frequency of natural hazards (floods in central and southem Europe and stonns on the Dutch North Sea coast), the impact of climate deterioration on grain prices and wine production, and finally, witch-hlllltS. The documentary data used for the reconstruction of seasonal and annual precipitation and temperatures in central Europe (Germany, Switzerland and the Czech Republic) include narrative sources, several types of proxy data and 32 weather diaries. Results were compared with long-tenn composite tree ring series and tested statistically by cross-correlating series of indices based OIl documentary data from the sixteenth century with those of simulated indices based on instrumental series (1901-1960). It was shown that series of indices can be taken as good substitutes for instrumental measurements. A corresponding set of weighted seasonal and annual series of temperature and precipitation indices for central Europe was computed from series of temperature and precipitation indices for Germany, Switzerland and the Czech Republic, the weights being in proportion to the area of each country. The series of central European indices were then used to assess temperature and precipitation anomalies for the 1901-1960 period using trmlsfer functions obtained from instrumental records. -

Alonso De Leon: Pathfinder in East Texas, 1686-1690

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 33 Issue 1 Article 6 3-1995 Alonso De Leon: Pathfinder in East exas,T 1686-1690 Donald E. Chipman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Chipman, Donald E. (1995) "Alonso De Leon: Pathfinder in East exas,T 1686-1690," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 33 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol33/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION ALONSO DE LEON: PATHfl'INDER IN EAST TEXAS, 1686-1 . ;;; D. I by Donald E. ChIpman ~ ftIIlph W .; . .. 6' . .,)I~l,". • The 1680s were a time of cnSiS for the northern frontle ewSliJrSl1' .Ibrity ..:: (Colonial Mexico). In New Mexico the decade began with a ~e, coor- ~~ dinated revolt involving most of the Pueblo Indians. The Great Rev 2!!V Z~~\(, forced the Spanish to abandon a province held continuously since 1598,"~~':;:"-~ claimed more than 400 lives. Survivors, well over 2,000 of them. retreated down the Rio Grande to El Paso del Rio del Norte. transforming it overnight from a way station and missionary outpost along the road to New Mexico proper into a focus of empire. From El Paso the first European settlement within the present boundaries of Texas. -

Staff Working Paper No. 845 Eight Centuries of Global Real Interest Rates, R-G, and the ‘Suprasecular’ Decline, 1311–2018 Paul Schmelzing

CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 -

Personal Agency at the Swedish Age of Greatness 1560–1720

Edited by Petri Karonen and Marko Hakanen Marko and Karonen Petri by Edited Personal Agency at the Swedish Age of Greatness 1560-1720 provides fresh insights into the state-building process in Sweden. During this transitional period, many far-reaching administrative reforms were the Swedish at Agency Personal Age of Greatness 1560–1720 Greatness of Age carried out, and the Swedish state developed into a prime example of the ‘power-state’. Personal Agency In early modern studies, agency has long remained in the shadow of the study of structures and institutions. State building in Sweden at the Swedish Age of was a more diversified and personalized process than has previously been assumed. Numerous individuals were also important actors Greatness 1560–1720 in the process, and that development itself was not straightforward progression at the macro-level but was intertwined with lower-level Edited by actors. Petri Karonen and Marko Hakanen Editors of the anthology are Dr. Petri Karonen, Professor of Finnish history at the University of Jyväskylä and Dr. Marko Hakanen, Research Fellow of Finnish History at the University of Jyväskylä. studia fennica historica 23 isbn 978-952-222-882-6 93 9789522228826 www.finlit.fi/kirjat Studia Fennica studia fennica anthropologica ethnologica folkloristica historica linguistica litteraria Historica The Finnish Literature Society (SKS) was founded in 1831 and has, from the very beginning, engaged in publishing operations. It nowadays publishes literature in the fields of ethnology and folkloristics, linguistics, literary research and cultural history. The first volume of the Studia Fennica series appeared in 1933. Since 1992, the series has been divided into three thematic subseries: Ethnologica, Folkloristica and Linguistica. -

Stony Brook University

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Invasions, Insurgency and Interventions: Sweden’s Wars in Poland, Prussia and Denmark 1654 - 1658. A Dissertation Presented by Christopher Adam Gennari to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Stony Brook University May 2010 Copyright by Christopher Adam Gennari 2010 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Christopher Adam Gennari We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Ian Roxborough – Dissertation Advisor, Professor, Department of Sociology. Michael Barnhart - Chairperson of Defense, Distinguished Teaching Professor, Department of History. Gary Marker, Professor, Department of History. Alix Cooper, Associate Professor, Department of History. Daniel Levy, Department of Sociology, SUNY Stony Brook. This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School """"""""" """"""""""Lawrence Martin "" """""""Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation Invasions, Insurgency and Intervention: Sweden’s Wars in Poland, Prussia and Denmark. by Christopher Adam Gennari Doctor of Philosophy in History Stony Brook University 2010 "In 1655 Sweden was the premier military power in northern Europe. When Sweden invaded Poland, in June 1655, it went to war with an army which reflected not only the state’s military and cultural strengths but also its fiscal weaknesses. During 1655 the Swedes won great successes in Poland and captured most of the country. But a series of military decisions transformed the Swedish army from a concentrated, combined-arms force into a mobile but widely dispersed force. -

Robert Greene and the Theatrical Vocabulary of the Early 1590S Alan

Robert Greene and the Theatrical Vocabulary of the Early 1590s Alan C. Dessen [Writing Robert Greene: Essays on England’s First Notorious Professional Writer, ed. Kirk Melnikoff and Edward Gieskes (Aldershot and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2008), pp. 25-37.\ Here is a familiar tale found in literary handbooks for much of the twentieth century. Once upon a time in the 1560s and 1570s (the boyhoods of Marlowe, Shakespeare, and Jonson) English drama was in a deplorable state characterized by fourteener couplets, allegory, the heavy hand of didacticism, and touring troupes of players with limited numbers and resources. A first breakthrough came with the building of the first permanent playhouses in the London area in 1576- 77 (The Theatre, The Curtain)--hence an opportunity for stable groups to form so as to develop a repertory of plays and an audience. A decade later the University Wits came down to bring their learning and sophistication to the London desert, so that the heavyhandedness and primitive skills of early 1580s playwrights such as Robert Wilson and predecessors such as Thomas Lupton, George Wapull, and William Wager were superseded by the artistry of Marlowe, Kyd, and Greene. The introduction of blank verse and the suppression of allegory and onstage sermons yielded what Willard Thorp billed in 1928 as "the triumph of realism."1 Theatre and drama historians have picked away at some of these details (in particular, 1576 has lost some of its luster or uniqueness), but the narrative of the University Wits' resuscitation of a moribund English drama has retained its status as received truth. -

Letters from New Spain, Mid 1500S

Library of Congress Letters Home: Correspondence from Spanish colonists in Mexico City and Puebla to relatives * in Spain, 1558-1589 Mexico City and Puebla, detail of A. Ysarti, Provincia d[e] S. Diego de Mexico EXCERPTS en la nueba Espana . , ca. 1682 Antonio Mateos, a farmer in Puebla, to his wife in Spain, 1558 Very longed-for lady wife: doing the best thing for you and me. Give my About a year and a half ago I wrote you greetings to my sisters and to your brother and greatly desiring to know about you and the health mine and to my nephews, and also to all of your of yourself and my son Antón Mateos, and also cousins and relatives and neighbors, and greet about my sisters and your brother and mine Antón everyone who asks for me. I haven’t heard from Pérez, but I have never had a letter or reply since my cousins for four years and nine months; they you wrote when I sent you money by Juan de left Mexico City and went I don’t know where, Ocampo. With the desire to prepare for your nor do I know if they are alive or dead. No more, arrival, I went to the valley of Atlixco, where they but may our Lord keep you in his hand for me. grow two crops of wheat a year, one irrigated and the other watered by rainfall; I thought that we could be there the rest of our Library of Congress lives. I was a farmer for a year in company with another farmer there; for the future I had found lands and bought four pair of oxen and everything necessary for our livelihood, since the land is the most luxuriant, and plenteous and abundant in grain, that there is in all New Spain. -

Federal Research Division Country Profile: Bulgaria, October 2006

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Bulgaria, October 2006 COUNTRY PROFILE: BULGARIA October 2006 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of Bulgaria (Republika Bŭlgariya). Short Form: Bulgaria. Term for Citizens(s): Bulgarian(s). Capital: Sofia. Click to Enlarge Image Other Major Cities (in order of population): Plovdiv, Varna, Burgas, Ruse, Stara Zagora, Pleven, and Sliven. Independence: Bulgaria recognizes its independence day as September 22, 1908, when the Kingdom of Bulgaria declared its independence from the Ottoman Empire. Public Holidays: Bulgaria celebrates the following national holidays: New Year’s (January 1); National Day (March 3); Orthodox Easter (variable date in April or early May); Labor Day (May 1); St. George’s Day or Army Day (May 6); Education Day (May 24); Unification Day (September 6); Independence Day (September 22); Leaders of the Bulgarian Revival Day (November 1); and Christmas (December 24–26). Flag: The flag of Bulgaria has three equal horizontal stripes of white (top), green, and red. Click to Enlarge Image HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Early Settlement and Empire: According to archaeologists, present-day Bulgaria first attracted human settlement as early as the Neolithic Age, about 5000 B.C. The first known civilization in the region was that of the Thracians, whose culture reached a peak in the sixth century B.C. Because of disunity, in the ensuing centuries Thracian territory was occupied successively by the Greeks, Persians, Macedonians, and Romans. A Thracian kingdom still existed under the Roman Empire until the first century A.D., when Thrace was incorporated into the empire, and Serditsa was established as a trading center on the site of the modern Bulgarian capital, Sofia. -

Baltic Towns030306

Seventeenth Century Baltic Merchants is one of the most frequented waters in the world - if not the Tmost frequented – and has been so for the last thousand years. Shipping and trade routes over the Baltic Sea have a long tradition. During the Middle Ages the Hanseatic League dominated trade in the Baltic region. When the German Hansa definitely lost its position in the sixteenth century, other actors started struggling for the control of the Baltic Sea and, above all, its port towns. Among those coun- tries were, for example, Russia, Poland, Denmark and Sweden. Since Finland was a part of the Swedish realm, ”the eastern half of the realm”, Sweden held positions on both the east and west coasts. From 1561, when the town of Reval and adjacent areas sought protection under the Swedish Crown, ex- pansion began along the southeastern and southern coasts of the Baltic. By the end of the Thirty Years War in 1648, Sweden had gained control and was the dom- inating great power of the Baltic Sea region. When the Danish areas in the south- ern part of the Scandinavian Peninsula were taken in 1660, Sweden’s policies were fulfilled. Until the fall of Sweden’s Great Power status in 1718, the realm kept, if not the objective ”Dominium Maris Baltici” so at least ”Mare Clausum”. 1 The strong military and political position did not, however, correspond with an economic dominance. Michael Roberts has declared that Sweden’s control of the Baltic after 1681 was ultimately dependent on the good will of the maritime powers, whose interests Sweden could not afford to ignore.2 In financing the wars, the Swedish government frequently used loans from Dutch and German merchants.3 Moreover, the strong expansion of the Swedish mining industries 1 Rystad, Göran: Dominium Maris Baltici – dröm och verklighet /Mare nostrum. -

The Reform Treatises and Discourse of Early Tudor Ireland, C

The Reform Treatises and Discourse of Early Tudor Ireland, c. 1515‐1541 by Chad T. Marshall BA (Hons., Archaeology, Toronto), MA (History and Classics, Tasmania) School of Humanities Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania, December, 2018 Declaration of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. Signed: _________________________ Date: 7/12/2018 i Authority of Access This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying and communication in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Signed: _________________________ Date: 7/12/2018 ii Acknowledgements This thesis is for my wife, Elizabeth van der Geest, a woman of boundless beauty, talent, and mystery, who continuously demonstrates an inestimable ability to elevate the spirit, of which an equal part is given over to mastery of that other vital craft which serves to refine its expression. I extend particular gratitude to my supervisors: Drs. Gavin Daly and Michael Bennett. They permitted me the scope to explore the arena of Late Medieval and Early Modern Ireland and England, and skilfully trained wide‐ranging interests onto a workable topic and – testifying to their miraculous abilities – a completed thesis. Thanks, too, to Peter Crooks of Trinity College Dublin and David Heffernan of Queen’s University Belfast for early advice. -

Female Wits” Controversy: Gender, Genre, and Printed Plays, 1670–16991

Plotting the “Female Wits” Controversy: Gender, Genre, and Printed Plays, 1670–16991 Mattie Burkert Utah State University [email protected] At the end of the 1694–95 theatrical season, a group of actors defected from the United Company, housed at the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane, to begin their own cooperative. The split of London’s theatrical monopoly into two rival playhouses—Christopher Rich’s “Patent Company” at Drury Lane and Thomas Betterton’s “Actors’ Company” at Lincoln’s Inn Fields—generated demand for new plays that might help either house gain the advantage. This situation cre- ated opportunities for novice writers, including an unprecedented number of women. Paula Backscheider has calculated that more than one-third of the new plays in the 1695–96 season were written by, or adapted from work by, women, including Delarivier Manley, Catherine Trotter, and Mary Pix (1993, 71). This group quickly became the target of a satirical backstage drama, The Female Wits: or, the Triumvirate of Poets at Rehearsal, modeled after George Vil- liers’s 1671 sendup of John Dryden, The Rehearsal. The satire, which was likely performed at Drury Lane in fall 1696, was partially the Patent Company’s re- venge on Manley for withdrawing her play The Royal Mischief during rehearsals the previous spring and taking it to Betterton. However, The Female Wits was also a broader attack on the pretensions of women writers, whom it portrayed as frivolous, self-important upstarts reviving the overblown heroic tragedy of the 1660s and 1670s with an additional layer of feminine sentimentality.2 1 This research was made possible by a grant from the Andrew W. -

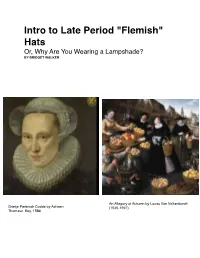

"Flemish" Hats Or, Why Are You Wearing a Lampshade? by BRIDGET WALKER

Intro to Late Period "Flemish" Hats Or, Why Are You Wearing a Lampshade? BY BRIDGET WALKER An Allegory of Autumn by Lucas Van Valkenborch Grietje Pietersdr Codde by Adriaen (1535-1597) Thomasz. Key, 1586 Where Are We Again? This is the coast of modern day Belgium and The Netherlands, with the east coast of England included for scale. According to Fynes Moryson, an Englishman traveling through the area in the 1590s, the cities of Bruges and Ghent are in Flanders, the city of Antwerp belongs to the Dutchy of the Brabant, and the city of Amsterdam is in South Holland. However, he explains, Ghent and Bruges were the major trading centers in the early 1500s. Consequently, foreigners often refer to the entire area as "Flemish". Antwerp is approximately fifty miles from Bruges and a hundred miles from Amsterdam. Hairstyles The Cook by PieterAertsen, 1559 Market Scene by Pieter Aertsen Upper class women rarely have their portraits painted without their headdresses. Luckily, Antwerp's many genre paintings can give us a clue. The hair is put up in what is most likely a form of hair taping. In the example on the left, the braids might be simply wrapped around the head. However, the woman on the right has her braids too far back for that. They must be sewn or pinned on. The hair at the front is occasionally padded in rolls out over the temples, but is much more likely to remain close to the head. At the end of the 1600s, when the French and English often dressed the hair over the forehead, the ladies of the Netherlands continued to pull their hair back smoothly.