Conservation Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extract Catalogue for Auction 3

Online Auction 3 Page:1 Lot Type Grading Description Est $A FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 958 FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 958 Balance of collection including 1931-71 fixtures (7); Tony Locket AFL Goalkicking Estimate A$120 Record pair of badges; football cards (20); badges (7); phonecard; fridge magnets (2); videos (2); AFL Centenary beer coasters (2); 2009 invitation to lunch of new club in Reserve A$90 Sydney, mainly Fine condition. (40+) Lot 959 FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 959 Balance of collection including Kennington Football Club blazer 'Olympic Premiers Estimate A$100 1956'; c.1998-2007 calendars (21); 1966 St.Kilda folk-art display with football cards (7) & Reserve A$75 Allan Jeans signature; photos (2) & footy card. (26 items) Lot 960 FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 960 Collection including 'Mobil Football Photos 1964' [40] & 'Mobil Footy Photos 1965' [38/40] Estimate A$250 in albums; VFL Park badges (15); members season tickets for VFL Park (4), AFL (4) & Reserve A$190 Melbourne (9); books/magazines (3); 'Football Record' 2013 NAB Cup. (38 items) Lot 961 FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 961 Balance of collection including newspapers/ephemera with Grand Final Souvenirs for Estimate A$100 1974 (2), 1985 & 1989; stamp booklets & covers; Member's season tickets for VFL Park (6), AFL (2) & Melbourne (2); autographs (14) with Gary Ablett Sr, Paul Roos & Paul Kelly; Reserve A$75 1973-2012 bendigo programmes (8); Grand Final rain ponchos. (100 approx) Page:2 www.abacusauctions.com.au 20 - 23 November 2020 Lot 962 FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 962 1921 FOURTH AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL CARNIVAL: Badge 'Australian Football Estimate A$300 Carnival/V/Perth 1921'. -

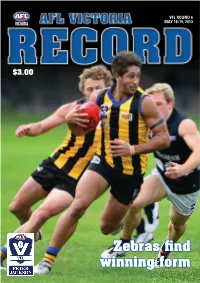

VFL Record Rnd 6.Indd

VFL ROUND 6 MAY 18-19, 2013 $3.00 ZZebrasebras fi nndd wwinninginning fformorm WWAFLAFL 117.16.1187.16.118 d VVFLFL 115.11.1015.11.101 Give exit fees the boot. And lock-in contracts the hip and shoulder. AlintaAlinta EnerEnergy’sgy’s Fair GGoo 1155 • NoNo lock-inlock-in contractscontracts • No exitexit fees • 15%15% off your electricity usageusage* forfor as lonlongg as you continue to be on this planplan 18001800 46 2525 4646 alintaenergy.com.aualintaenergy.com.au *15% off your electricity usage based on Alinta Energy’s published Standing Tariffs for Victoria. Terms and conditionsconditions apply.apply. NNotot avaavailableilable wwithith sosolar.lar. EDITORIAL State football CONGRATULATIONS to the West Australian Football League for its victory against the Peter Jackson VFL last Saturday at Northam. The host State emerged from a typically hard fought State player, as well as to Wayde match with a 17-point win after grabbing the lead midway Twomey, who won the WAFL’s through the last quarter. Simpson Medal. Full credit to both teams for the manner in which they What was particularly pleasing played; the game showcased the high standard and quality was the opportunity afforded to so many players to play football that exists in the respective State Leagues. State representative football for the fi rst time. There were One would suspect that a number of players from the game just four players returning to the Peter Jackson VFL team will come under the scrutiny of AFL recruiters come the end that defeated Tasmania last year. of the year. Last year’s Peter Jackson VFL team contained And, the average age of the Peter Jackson VFL team of 24 six players who are now on an AFL list. -

17 October 2019

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-NINTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION THURSDAY, 17 OCTOBER 2019 Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor The Honourable LINDA DESSAU, AC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable KEN LAY, AO, APM The ministry Premier ........................................................ The Hon. DM Andrews, MP Deputy Premier and Minister for Education ......................... The Hon. JA Merlino, MP Treasurer, Minister for Economic Development and Minister for Industrial Relations ........................................... The Hon. TH Pallas, MP Minister for Transport Infrastructure ............................... The Hon. JM Allan, MP Minister for Crime Prevention, Minister for Corrections, Minister for Youth Justice and Minister for Victim Support .................... The Hon. BA Carroll, MP Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change, and Minister for Solar Homes ................................................. The Hon. L D’Ambrosio, MP Minister for Child Protection and Minister for Disability, Ageing and Carers ....................................................... The Hon. LA Donnellan, MP Minister for Mental Health, Minister for Equality and Minister for Creative Industries ............................................ The Hon. MP Foley, MP Attorney-General and Minister for Workplace Safety ................. The Hon. J Hennessy, MP Minister for Public Transport and Minister for Ports and Freight -

Planning Template

My topic: History of Melbourne Football Club_____________________ Facts that already I know: New information from my research: They have won 12 VFL/AFL Premierships. Their last Premiership was → Ron Barassi was the captain of Melbourne Demons in 1964. in 1964. → There is a statue of Ron Barassi at the MCG Melbourne Football club is the oldest professional sporting club in → Melbourne Demons and the Geelong Cats are the two oldest AFL teams in the world starting in 1858. the league. Geelong formed their club in 1859. They wear red and blue and it looks like this: → There have been 22 changes to the jersey since 1858. Their first one looked like this and the players had to tie it up at the front. Their home ground is the MCG (Melbourne Cricket Ground) → The MCG was built in 1853 when the then 15-year-old Melbourne Cricket Club was forced by the government to move from its site because the tracks of Australia's first steam train was to pass through the oval. Other interesting facts from my research: → The Demon’s first captain was the captain of the Victorian Cricket Team. He started the football team to keep the cricketers fit in winter. → The ‘Norm Smith medal’ is given to the best player in an AFL Grand Final. He played 301 games for Melbourne FC. From 1952 to 1967. → → My topic: ____________________________________________________ Facts that already I know: New information from my research: → → → → Other interesting facts from my research: → → → → → Informative Writing — Worksheet Name Date Informative Paragraph — Planning Template Introductory sentence: Introduce the subject using a clear topic sentence. -

2020 Coburg FC Annual Report

COBURG FOOTBALL CLUB LIMITED FOUNDED 1891 INCORPORATED 1980 Premiers: 1926-27-28-70-74-79-88-89 Runners Up: 1932-33-34-51-59-80-86-07 th 130 A NNUAL REPORT To be presented to the Members at the Annual General Meeting to be held virtually via zoom meeting on Monday February 8th 2021. 1 CFC OFFICE BEARERS - Season 2020 PRESIDENT: Matthew Price VICE PRESIDENT: Dario Ascenzo TREASURER: Steve Russo DIRECTOR: Nelson Brown DIRECTOR: Tim Martin DIRECTOR: Alex Sapurmas DIRECTOR: Cecille Callaghan DIRECTOR: Kerion Lawson DIRECTOR: John Alducci GENERAL MANAGER: Sebastian Spagnuolo SENIOR COACH: Andrew Sturgess JUNIOR FOOTBALL CO-ORDINATOR: Angela Livingstone 2 Coburg Football Club -2020 Annual Report PRESIDENT’S REPORT Greetings to all the Coburg Football Club Family! I hope you and your family are all safe and well. It has certainly been an historic year for all the wrong reasons around the world. Firstly, our thoughts go out to any of the Coburg FC Family who have lost loved ones during this time, the year has been more difficult for you than most and we are sincerely thinking of you. There have been so many positive news stories coming out of Coburg FC this year that have been shared on our various Social Media channels, to recap: ● Coburg FC have been granted a license to participate in the VFL’s 2021 competition! This will see us take the Coburg brand and those of our sponsors to NSW & Queensland as part of the biggest second tier competition in Australia. ● Coburg have finally established a Women’s team to play in the South Eastern Women’s Football League in 2021! A huge thanks to the Women’s team led by Liam Cavanagh and the players for their enthusiasm and commitment! ● Coburg Junior and FIDA teams will return in 2021! Many thanks to Angela and Piero for their time and passion. -

Encyclopedia of Australian Football Clubs

Full Points Footy ENCYCLOPEDIA OF AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL CLUBS Volume One by John Devaney Published in Great Britain by Full Points Publications © John Devaney and Full Points Publications 2008 This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior written permission. Every effort has been made to ensure that this book is free from error or omissions. However, the Publisher and Author, or their respective employees or agents, shall not accept responsibility for injury, loss or damage occasioned to any person acting or refraining from action as a result of material in this book whether or not such injury, loss or damage is in any way due to any negligent act or omission, breach of duty or default on the part of the Publisher, Author or their respective employees or agents. Cataloguing-in-Publication data: The Full Points Footy Encyclopedia Of Australian Football Clubs Volume One ISBN 978-0-9556897-0-3 1. Australian football—Encyclopedias. 2. Australian football—Clubs. 3. Sports—Australian football—History. I. Devaney, John. Full Points Footy http://www.fullpointsfooty.net Introduction For most football devotees, clubs are the lenses through which they view the game, colouring and shaping their perception of it more than all other factors combined. To use another overblown metaphor, clubs are also the essential fabric out of which the rich, variegated tapestry of the game’s history has been woven. -

Official Handbook

2013-14 VWCA Official Handbook 2013-14 OFFICIAL HANDBOOK 2013-14 VVWWCCAA CCoo mmmmuunniittyy CCrriicckkeett AAwwaarrddss NNiigghhtt th Friday 9 May 2014 Bayview on the Park For more information please contact the VWCA on 9653 1181 or [email protected] Victorian Women’s Cricket Association 2013/14 VWCA Score Hotline 9653 1181 (One Day Shield, North West & South East Competitions) Premier Cricket Score Hotline 9653 1131 (Premier Firsts & Premier Seconds Competitions) VWCA Information Line For information on umpire appointments: 1902 210 578 (One Day Shield, North West & South East Competitions) (Rate $0.83 per minute, including GST - mobile & pay phones extra) Premier Cricket Ground Status Reporting 0413 888 391 (Premier Firsts & Premier Seconds Competitions) 1 Season 2013/14 Office Bearers & Contacts President Rachel Derham Vice Presidents Robyn Calder Julie Savage Tamara Mason Premier & Community Erini Gianakopoulos Club Cricket Officer Cricket Victoria 86 Jolimont St Jolimont Vic 3002 P: 9653 1181 F: 9653 1144 E: [email protected] W: vwca.cricketvictoria.com.au Match Results & Jill Crowther AH: 9546 4967 Registration Secretary Pennant Secretary Katherine Broome M: 0425 791 463 Umpires Advisor Joe Briganti M: 0418 115 365 Committees Board Alanna Duffy, Kirsty Henshall, Peter Kaspar, Lorraine Taylor & Clare Warren Cricket Victoria Julie Savage Delegate Rules Committee Russell Turner Disciplinary Joe Briganti, Alanna Duffy, Gail Schmidt, Committee Russell Turner & Lorraine Taylor Appeals Chairperson David Peers -

One of the Boys: the (Gendered) Performance of My Football Career

One of the Boys: The (Gendered) Performance of My Football Career Ms. Kasey Symons PhD Candidate 2019 The Institute for Sustainable Industries and Liveable Cities (ISILC), Victoria University, Australia. Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Abstract: This PhD via creative work comprises an exegesis (30%) and accompanying novel, Fan Fatale (70%), which seek to contribute a creative and considered representation of some women who are fans of elite male sports, Australian Rules football in particular. Fictional representations of Australian Rules football are rare. At the time of submission of this thesis, only three such works were found that are written by women aimed to an older readership. This project adds to this underrepresented space for women writing on, and contributing their experiences to, the culture of men’s football. The exegesis and novel creatively addresses the research question of how female fans relate to other women in the sports fan space through concepts of gender bias, performance, and social surveillance. Applying the lens of autoethnography as the primary methodology to examine these notions further allows a deeper, reflexive engagement with the research, to explore how damaging these performances can be for the relationships women can have to other women. In producing this exegesis and accompanying novel, this PhD thesis contributes a new and creative way to explore the gendered complications that surround the sports fan space for women. My novel, Fan Fatale, provides a narrative which raises questions about the complicit positions women can sometimes occupy in the name of fandom and conformity to expected gendered norms. -

Xref Football Catalogue for Auction

Auction 241 Page:1 Lot Type Grading Description Est $A SPORTING MEMORABILIA - General & Miscellaneous Lots 1 Balance of collection including 'The First Over' silk cricket picture; Wayne Carey mini football locker; 1973 Caulfield Cup glass; 'Dawn Fraser' swimming goggles; 'Greg Norman' golf glove; VHS video cases signed by Lionel Rose, Jeff Fenech, Dennis Lillee, Kevin Sheedy, Robert Harvey, Peter Hudson, Dennis Pagan & Wayne Carey. (12 items) 100 3 Balance of collection including 'Summit' football signed John Eales; soccer shirts for Australia & Arsenal; Fitzroy football jumper with number '5' (Bernie Quinlan); sports books (10), mainly Fine condition. (14) 80 5 Ephemera 'Order of Service' books for the funerals of Ron Clarke (4), Arthur Morris, Harold Larwood, David Hookes, Graeme Langlands, Roy Higgins, Dick Reynolds, Bob Rose (2), Merv Lincoln (2), Bob Reed & Paul Rak; Menus (10) including with signatures of Ricky Ponting (2), Mike Hussey, Meg Lanning, Henry Blofeld, Graham Yallop, Jeff Moss, Mick Taylor, Ray Bright, Francis Bourke. 150 6 Figurines collection of cold cast bronze & poly-resin figurines including shot putter, female tennis player, male tennis player, sprinter on blocks, runner breasting tape, relay runner; also 'Wally Lewis - The King of Lang Park'; 'Joffa' bobblehead & ProStar headliner of Gary Ablett Snr. (9) 150 7 Newspapers interesting collection featuring sports-related front page images and feature stories relating to football, cricket, boxing, horse racing & Olympics, mainly 2010-2019, also a few other topics including -

VFL Record Rnd 4.Indd

VFL ROUND 4 APRIL 26-28, 2013 $3.00 WWilliamstownilliamstown wwinsins wwesternestern dderby...erby... aagaingain SSandringhamandringham 116.12.1086.12.108 ddww PPortort MMelbourneelbourne 116.12.1086.12.108 (Photos: Dave Savell) WWilliamstownilliamstown 119.15.1299.15.129 d WWerribeeerribee TTigersigers 55.16.46.16.46 Give exit fees the boot. And lock-in contracts the hip and shoulder. AlintaAlinta EnerEnergy’sgy’s Fair GGoo 1155 • NoNo lock-inlock-in contractscontracts • No exitexit fees • 15%15% off your electricity usageusage* forfor as lonlongg as you continue to be on this planplan 18001800 46 2525 4646 alintaenergy.com.aualintaenergy.com.au *15% off your electricity usage based on Alinta Energy’s published Standing Tariffs for Victoria. Terms and conditionsconditions apply.apply. NNotot avaavailableilable wwithith sosolar.lar. EDITORIAL Drug education and awareness the focus AS news of the recent ACC Report and ASADA follow up continues to prevail throughout the media, it’s timely to highlight AFL Victoria’s position. First and foremost illicit and performance-enhancing that our education strategies are substances will not be tolerated in our game. Breaches appropriate. of the AFL’s Anti-Doping Code rightly results in heavy ASADA doesn’t detail its testing regime, for the integrity of sanctions. its testing program, and nor does AFL Victoria ever expect to Education and awareness are two unwavering tenets that know the intricate operation details of the testing program. must prevail in understanding the game’s Anti-Doping policy. Every registered player, including those within community AFL Victoria works with all VFL Clubs to help educate level in country and metropolitan Leagues, can be tested by players and offi cials regarding the requirements of the ASADA. -

Box Hill Hawks Football Club Limited

Box Hill Hawks Football Club Limited ABN 77 090 410 227 65th Annual Report 2015 BOX HILL HAWKS – VICTORIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE – CLUB CHAMPIONS 2015 Co-Major Partners Platinum Partners Coaches Partner Apparel Partner Community Partner Hydration Partner Corporate Partners 7–Eleven Elite Property Care Musashi Box Hill R.S.L. Flex Art Pompeo’s Pizza Restaurant Box Hill Self Storage Grainstore Bakehouse Prom Coast Holiday Units Col Smith Garden Supplies Harcourts Real Estate – Balwyn Slumbertrek Complete Carpet Co Hine Hire Victorian Rehab Centre Creative Framing MBCM Strata Specialists – Box Hill Weatherson Foods DayTec Australia Melbourne Mail Management Box Hill Hawks Football Club Limited 65th Annual Report 2015 Table of Contents Off-field Operations Staff List 2 President’s Report 3 General Manager’s Report 3 Senior Coach’s Report 5 Appreciation, Congratulations, Obituary, Award of Life Membership, 6 Directors Attendances at Meetings On-field Performance Match Results – Seniors 7 Match Results – Development Team 8 V.F.L. Representation 9 Player Statistics – Seniors 10 Player Statistics – Development Team 11 Trophy List, Home Ground Attendances, Medal Voting, Ladders 14 History Statistics – Senior Grade – 1951 to 2015 15 Record Against Other V.F.A. / V.F.L. Clubs – Senior Grade – 1951 to 2015 16 Season by Season V.F.A. / V.F.L. Record – Senior Grade – 1951 to 2015 17 Statistics – Reserve Grade – 1951 to 2015, Statistics – V.F.A. Thirds – 1952 to 1994 18 Season by Season V.F.A. / V.F.L. Record – Reserve Grade – 1951 to 2015 19 Honours Life -

Time on Annual Journal of the New South Wales Australian Football History Society

Time On Annual Journal of the New South Wales Australian Football History Society 2013 Time on: Annual Journal of the NSW Australian Football History Society. 2012. Croydon Park NSW, 2013 ISSN 2202-5049 Time On is published annually by the NSW Australian Football History Society Inc for members of the Society. It is distributed to all current members free of charge. It is based on football stories originally published on the Society’s website during 2012. Contributions from members for future editions are welcome and should be discussed in the first instance with the president, Ian Granland OAM, on 0412 798 521, who will arrange with you for your tale to be submitted. Published by: The NSW Australian Football History Society Inc. 40 Hampton Street, Croydon Park, NSW, 2133 P O Box 98, Croydon Park NSW 2133 ABN 48 204 892 073 Contents Editorial ........................................................................................................................................................... 1 The start of football in Sydney ......................................................................................................................... 3 The first rules ............................................................................................................................................ 4 The first game in Sydney – in 1866? .......................................................................................................... 6 1881: The Dees just roll Easts, then Sydney .............................................................................................