Slover-Linett-Theater-Revenue-Study-1.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theater Events: Body Image at Play in Clockwise's 'Impenetrable'

dailyherald.com http://www.dailyherald.com/article/20141010/entlife/141019986/ Theater events: Body image at play in Clockwise's 'Impenetrable' Barbara Vitello Body image A spa billboard showing a gorgeous, bikini-clad woman with arrows pointing to her imperfections and how they could be improved provokes outrage in a Chicago suburb in "Impenetrable" by Mia McCullough. Judy Blue directs Clockwise Theatre's production of the 2012 play about body image and perception and how this advertisement affects men and women in the community. Opens at 8 p.m. Friday, Oct. 10, at 221 N. Genesee St., Waukegan. $12, $20. See clockwisetheatre.org. A sneak peek The Actors Gymnasium offers a glimpse of new works as part of its Circus in Progress series showcasing circus arts. Featured artists include Striding Lion dance theater along with trapeze artist Camille Swift and Akemi Berry on silks. Next up is "A Circus Night's Dream," written and directed by The House Theatre's Chris Mathews. 4:30 and 7:30 p.m. Saturday, Oct. 11, at the Noyes Cultural Arts Center, 927 Noyes St., Evanston. $15. (847) 328-2795 or actorsgymnasium.org. Devil has his 'Day' Signal Ensemble Theatre opens its season with the world premiere of "Devil's Day Off" by Jon Steinhagen ("Blizzard '67," "Dating Walter Dante"). Set during a record-breaking heat wave that is accompanied by massive power outages, "Devil's Day Off" chronicles the fear, humor and heroism of the event through multiple vignettes. Co-artistic director Ronan Mara directs the premiere, which features 13 actors playing 100 characters. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1982

Nat]onal Endowment for the Arts National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Council on the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1982. Respectfully, F. S. M. Hodsoll Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. March 1983 Contents Chairman’s Statement 3 The Agency and Its Functions 6 The National Council on the Arts 7 Programs 8 Dance 10 Design Arts 30 Expansion Arts 46 Folk Arts 70 Inter-Arts 82 International 96 Literature 98 Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television 114 Museum 132 Music 160 Opera-Musical Theater 200 Theater 210 Visual Arts 230 Policy, Planning and Research 252 Challenge Grants 254 Endowment Fellows 259 Research 261 Special Constituencies 262 Office for Partnership 264 Artists in Education 266 State Programs 272 Financial Summary 277 History of Authorizations and Appropriations 278 The descriptions of the 5,090 grants listed in this matching grants, advocacy, and information. In 1982 Annual Report represent a rich variety of terms of public funding, we are complemented at artistic creativity taking place throughout the the state and local levels by state and local arts country. These grants testify to the central impor agencies. tance of the arts in American life and to the TheEndowment’s1982budgetwas$143million. fundamental fact that the arts ate alive and, in State appropriations from 50 states and six special many cases, flourishing, jurisdictions aggregated $120 million--an 8.9 per The diversity of artistic activity in America is cent gain over state appropriations for FY 81. -

STATEMENT of PRINCIPLE No One Should Be Forced to Choose

STATEMENT OF PRINCIPLE No one should be forced to choose between her personal safety and dignity, and her job. But too often in the theater community this is exactly the choice that women must make. Sexual discrimination and harassment and gender-based violence often occur in the intimate and physical context of a theater production. Victims of such conduct face a stark choice between continuing to work in close collaboration with their abuser and quitting the show. Few can afford to give up a job and lose not only income, but also the opportunity for career advancement. There is a sense in the community that it is not necessarily in a victim’s best interest to report abuse because of fear that the response will be insufficient and open her up to retribution. In addition, many instances of abuse happen outside of the physical boundaries of a theater. No theater, union or guild currently takes responsible for handling such cases. However, the two people involved will most likely have to work together the next day or in another production, and the victims are left to deal with the aftermath by themselves. In the face of these realities, victims often choose silence and the abuse is allowed to continue. It is time for the theater community to break its own silence on harassment and abuse and formally address the problem. The reality is that those who behave abusively are generally in positions of power. Artistic directors hold the power to employ, playwrights have hiring approval; removing a director mid-rehearsal puts an entire production in doubt; losing a celebrity from the cast hurts ticket sales. -

JAMES VINCENT MEREDITH SAG, AFTRA, AEA Height: 6’1” Hair Color: Brown Eye Color: Black

JAMES VINCENT MEREDITH SAG, AFTRA, AEA Height: 6’1” Hair Color: Brown Eye Color: Black TELEVISION FARGO Series Regular FX Chicago Med Guest Star (recurring) NBC Betrayal Recurring ABC Boss Recurring (7 Episodes) Starz Chicago Code Guest Star (Recurring) FOX Detroit 1-8-7 Co-Star ABC Law & Order: SVU Principal NBC David Platt Undercover Double Life Narrator/Host Discovery Channel The Beast Guest Star A & E ER Guest Star NBC BROADWAY/NATIONAL TOUR Book of Mormon Mafala Hatimbi Eugene O’Neil Theatre Book of Mormon Mafala Hatimbi Jumamosi Tour Superior Donuts (Broadway) James Music Box Theatre, NY, NY THEATRE Ski Dubai Shahab Steppenwolf Theatre Company The Tempest Antonio Steppenwolf Theatre Company Someone Who’ll Watch Over Me Adam Canning Piven Theatre Workshop Superior Donuts James Hailey Steppenwolf Theatre Company Carter’s Way Oriole Carter Steppenwolf Theatre Company The Crucible John Proctor Steppenwolf Theatre Company Othello Othello Writer’s Theatre The King and I The Kralahome Drury Lane Theater The Bluest Eye Daddy, Soaphead New Victory Theater (Manhattan, NY) The Bluest Eye Daddy, Soaphead Steppenwolf Theatre Company The Duchess of Malfi Antonio Writer’s Theatre Much Ado about Nothing Don Pedro Chicago Shakespeare Theatre The Pain and the Itch Mr. Hadid Steppenwolf Theatre Company Take Me Out Davey Battle About Face at Steppenwolf Measure for Measure Provost Chicago Shakespeare Theatre King John Lord Pembroke Chicago Shakespeare Theatre Romeo and Juliet Lord Capulet Chicago Shakespeare Theatre Julius Caesar Cinna, Titinius Chicago Shakespeare Theatre Othello Othello Michigan Shakespeare Festival The Hobbit Gandalf First Stage, Milwaukee, WI Othello Othello Journeymen Theatre King Lear Edgar Piven Theatre Workshop Master Harold…and the boys Sam Journeymen Theatre American Voices Joe Piven Theatre Workshop Raisin in the Sun Asagai Goodman Theatre Doo Lister’s Blues Cozy, Catfish Onyx Theatre Amistad Voices Covey, Reverend Duncan YMCA East Texas Hot Links Boochie Onyx Theatre Kids For President, etc. -

Download Related

ChiCago international ConneCtions Fund The MacArthur Foundation established a fund on its thirtieth anniversary in 2008 to encourage a greater sharing of experiences and international learning between its local Chicago grantees and their counterparts in other countries. Its premise is that Chicago is a global city that benefits from interaction between its citizens and organizations and their counterparts outside of the United States. This program was renewed in 2009 and the original fund of $1 million was extended with an additional $500,000. AT a GLANCe • The Chicago International Connections Fund was established in January 2008 at the MacArthur Foundation’s 30th Anniversary Celebration. • The fund recognizes Chicago’s place as a global city that benefits from the interactions between its citizens and their counterparts outside of the United States. • The purpose of the fund was to help eligible Chicago-based nonprofit organizations further their work by making connections with organizations and individuals internationally. • Between June 2008 and September 2009, the Foundation awarded 39 grants to 35 organizations. • More than half of the grant recipients were arts and culture organizations, a quarter were community development organizations, and the remainder a mix of groups focused on juvenile justice, conservation, human rights, and reproductive health issues. • Almost 40 countries were touched by exchanges with 450 Chicagoans traveling abroad and 160 representatives from international organizations welcomed to Chicago. John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation February 2011 Chicago International Connections Fund BaCKGROUND able to garner additional funding from Concert Dance, Inc. Eligible applicants to the Chicago other sources for their programs as a $50,000 to support an exchange International Connections Fund included result of the experiences and program program between the contemporary nonprofit organizations in the Chicago development that occurred during the dance company and the Department of area that were recent grant recipients of exchange. -

Community Letter in Support of Nonpartisanship

Community Letter in Support of Nonpartisanship Updated September 5, 2017 Community Letter in Support of Nonpartisanship UPDATED September 5, 2017 The Honorable Paul Ryan The Honorable Mitch McConnell Speaker Senate Majority Leader H-232 The Capitol S-230 The Capitol Washington, D.C. 20515 Washington, D.C. 20510 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Chuck Schumer House Democratic Leader Senate Democratic Leader H-204 The Capitol S-221 The Capitol Washington, D.C. 20515 Washington, D.C. 20510 The Honorable Kevin Brady The Honorable Orrin Hatch Chairman, House Ways and Means Committee Chairman, Senate Committee on Finance 1102 Longworth House Office Building 219 Dirksen Senate Office Building Washington, D.C. 20515 Washington, D.C. 20510 The Honorable Richard Neal The Honorable Ron Wyden Ranking Member, House Ways and Means Committee Ranking Member, Senate Committee on 1139E Longworth House Office Building Finance Washington, D.C. 20515 219 Dirksen Senate Office Building Washington, D.C. 20510 Dear Speaker Ryan, Majority Leader McConnell, Leader Pelosi, Leader Schumer, Chairman Brady, Chairman Hatch, Ranking Member Neal, and Ranking Member Wyden: The undersigned organizations strongly oppose proposals that would politicize the charitable nonprofit and philanthropic community by repealing or weakening current federal tax law protections that prohibit 501(c)(3) organizations from endorsing, opposing, or contributing to political candidates. Nonpartisanship is a cornerstone principle that has strengthened the public’s trust of the charitable community. In exchange for enjoying tax-exempt status and the ability to receive tax-deductible contributions, 501(c)(3) organizations – charitable nonprofits, including religious congregations, and foundations – agree to not engage in “any political campaign on behalf of (or in opposition to) any candidate for public office.” That provision of law protects the integrity and independence of charitable nonprofits and foundations. -

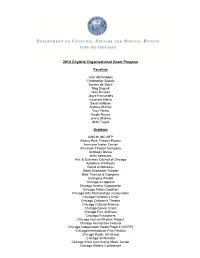

2014 Cityarts Program Grant

2014 CityArts Organizational Grant Program Panelists Julie Adrianopoli Christopher Audain Baraka de Soleil Meg Duguid Ilesa Duncan Joyce Fernandes Cayenne Harris Sarai Hoffman Andrew Micheli Troy Peters Nicole Reyna Jenny Shanks Willa Taylor Grantees 826CHI INC NFP Albany Park Theater Project American Indian Center American Theater Company Antibody Dance archi-treasures Arts & Business Council of Chicago Audience Architects Barrel of Monkeys Black Ensemble Theater Blair Thomas & Company Changing Worlds Chicago a cappella Chicago Access Corporation Chicago Artists Coalition Chicago Arts Partnerships in Education Chicago Children’s Choir Chicago Children's Theatre Chicago Cultural Alliance Chicago Dance Crash Chicago Film Archives Chicago Filmmakers Chicago Human Rhythm Project Chicago Humanities Festival Chicago Independent Radio Project (CHIRP) Chicago International Film Festival Chicago Public Art Group Chicago Sinfonietta Chicago West Community Music Center Chicago Writers Conference Chicago Youth Symphony Orchestras Child's Play Touring Theatre Chinese Fine Arts Society Clinard Dance Theater Community TV Network Congo Square Theatre Company Court Theatre Culture Shock Chicago, NFP Dance in the Parks, NFP DanceWorks Chicago DFBRL8R DuSable Museum of African American History eighth blackbird Performing Arts Association Elevarte Ensemble Español Spanish Dance Theater Erasing the Distance Fifth House Ensemble Free Spirit Media Fund for Innovative TV DBA Media Burn Archive Garfield Park Conservatory Alliance Gene Siskel Film Center Gilloury Institute Global Girls Inc. Grant Park Orchestral Association Griffin Theatre Company Groundswell Educational Films, NFP Gus Giordano's Jazz Dance Chicago, Inc. Heaven Gallery Hedwig Dances Hyde Park Art Center Hyde Park School of Dance InFusion Theatre Company Inner-City Muslim Action Network Institute of Puerto Rican Arts & Culture Instituto Cervantes of Chicago, Inc. -

Theater Events: Mooney Does 'Shakespeare on Demand' in 'Breakneck Hamlet'

dailyherald.com http://www.dailyherald.com/article/20150529/entlife/150528711/ Theater events: Mooney does 'Shakespeare on demand' in 'Breakneck Hamlet' Barbara Vitello Writer/director Tim Mooney stars in "Breakneck Hamlet" at Clockwise Theatre in Waukegan. COURTESY OF DALE JESSEN/CLOCKWISE THEATRE Fast-paced 'Hamlet' Clockwise Theatre presents the world premiere of "Breakneck Hamlet," writer/actor Tim Mooney's accelerated version of William Shakespeare's longest plays. Having introduced the melancholy Dane in Act 1, Mooney takes audience requests for the Bard's most famous speeches in the second act, which he dubs "Shakespeare on demand." Opens at 8 p.m. Friday, May 29, at 221 N. Genesee St., Waukegan. $20. (847) 775-1500 or clockwisetheatre.org. Standup showcase Standup comedians including Jordan Holmes and Peter Daniel perform as part of Comedy Shrine's monthly showcase of its favorite Midwest comedians. 8 p.m. Friday and Saturday, May 29-30, at 4034 Fox Valley Center Drive, Aurora. $20. (630) 585-0300 or comedyshrine.com. Playing his songs Theo Ubique Cabaret Theatre salutes the late composer Marvin Hamlisch as part of its summer showcase. "A Marvin Hamlisch Songbook" features standards like "The Way We Were" along with tunes from the musicals "A Chorus Line," "Sweet Smell of Success" and "They're Playing Our Song." Aaron Benham serves as musical director and arranger. Previews begin at 7:30 p.m. Thursday, June 4, at No Exit Cafe, 6970 N. Glenwood Ave., Chicago. The show opens June 6. $20-$34. (800) 595-4849 or theo-u.org. Other theater events • Lifeline Theatre, 6912 N. -

CALENDAR of NON-PROFIT EVENTS for METRO CHICAGO ADVERTISING SUPPLEMENT 3A January 1 FRIDAY – NEW YEAR’S DAY Harold E

Advertising Supplement ADVERTISING SUPPLEMENT 3A 2016 CRAIN’S CHICAGO BUSINESS BIG DATES CALENDAR OF NON-PROFIT EVENTS FOR METRO CHICAGO ADVERTISING SUPPLEMENT 3A January 1 FRIDAY – NEW YEAR’S DAY Harold E. Eisenberg Foundation Eisenopoly. Monopoly-themed evening raises Urban Initiatives Soccer Ball. A night of philanthropy, dancing, cocktails, funds for gastrointestinal cancer research and real estate education. 6:30 p.m., Revel appetizers and a silent auction to help create a safer, healthier and smarter Chicago. Fulton Market, Chicago. eisenbergfoundation.org. 7 p.m., Morgan Manufacturing, Chicago. urbaninitiatives.org. 10 SUNDAY 26 TUESDAY 30 SATURDAY ALSAC/St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital Red Carpet for Hope. Golden Globes viewing party with glitz, glamour and more. 5 p.m., Trump International International Latino Cultural Center Reel Film Club. Reception, a film Chicago Scots (Illinois Saint Andrews Society), Robert Burns Supper. Hotel & Tower, Chicago. stjude.org. highlighting a specific country, concluding with a discussion. 6 p.m., Facets Multimedia, Celebrate the life and work of the Scottish poet Robert Burns. 6 p.m., Union League Chicago. latinoculturalcenter.org. Club, Chicago. chicagoscots.org/burnssupper. 16 SATURDAY Archdiocese of Chicago, Celebrating Catholic Education Breakfast. Youth Services of Glenview/Northbrook, Firefighter Chili Cook Off and Ronald McDonald House Charities of Chicagoland and Northwest Supports the Caritas scholars program and programs coordinated through the Office of Trivia Contest. Also includes a chili tasting. 5 p.m., Youth Services of Glenview/ Indiana, Skate with the Greats. Mix and mingle with Chicago Catholic Schools. 7:15 a.m., Hyatt Regency Chicago. archchicago.org. Northbrook, Glenview. youthservicesgn.org. -

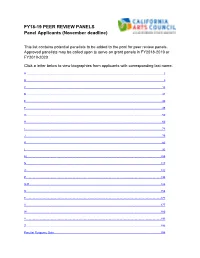

Panel Pool 2

FY18-19 PEER REVIEW PANELS Panel Applicants (November deadline) This list contains potential panelists to be added to the pool for peer review panels. Approved panelists may be called upon to serve on grant panels in FY2018-2019 or FY2019-2020. Click a letter below to view biographies from applicants with corresponding last name. A .............................................................................................................................................................................. 2 B ............................................................................................................................................................................... 9 C ............................................................................................................................................................................. 18 D ............................................................................................................................................................................. 31 E ............................................................................................................................................................................. 40 F ............................................................................................................................................................................. 45 G ............................................................................................................................................................................ -

Showtime 2004

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Cathy Taylor, Cathy Taylor Public Relations (773) 564-9564; [email protected] Ben Thiem, Director of Member Services, League of Chicago Theatres (312) 554-9800; [email protected] SUMMER 2019 THEATER HIGHLIGHTS Chicago, IL – Celebrating 2019 as the Year of Chicago Theatre, Chicago will continue to produce some of the most exciting work in the country this summer. Offerings from the city’s more than 250 producing theaters feature everything from the latest musicals to highly anticipated world premieres. For a comprehensive list of Chicago productions including a Summer Theatre Guide, visit the League of Chicago website, ChicagoPlays.com. Half-price tickets are available at HotTix.org or at the two Hot Tix half- price ticket locations: across from the Chicago Cultural Center at Expo72 (72 E. Randolph) and Block Thirty Seven, Shops at 108 N. State. Hot Tix offers half-price tickets for the current week and some performances in advance. “As we approach the halfway point of the Year of Chicago Theatre, I encourage every Chicagoan and visitor to attend a production by one of our 250 theater companies. This summer, there is a wide range of offerings, including an impressive number of musicals and world premieres. Simply, there is something for everyone,” notes Deb Clapp, Executive Director of the League of Chicago Theatres. The following is a selection of notable work playing in Chicago throughout the summer: New works and adaptations include: Lookingglass Theatre presents a new adaptation of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Mary Shelley’s unsettling story crackles to life as Victor Frankenstein must contend with his unholy creation. -

Explore Our Virtual Program

20|21 MICHAEL WEBER JEANNIE LUKOW Artistic Director Executive Director presents Featuring ANTHONY COURSER, PAM CHERMANSKY, CROSBY SANDOVAL, JAY TORRENCE, LEAH URZENDOWSKI & RYAN WALTERS Written by JAY TORRENCE Direction by HALENA KAYS This production was filmed during Porchlight Music Theatre’s premiere with The Ruffians at the Ruth Page Center for the Arts, December 13 - 27, 2019. Understudies for 2019 Production Nellie Reed: KAITLYN ANDREWS Henry Gilfoil/Eddie Foy: DAVE HONIGMAN Fancy Clown: JAY TORRENCE Faerie Queen/Robert Murray: RAWSON VINT Choreography by LEAH URZENDOWSKI Additional 2019 Choreography by ARIEL ETANA TRIUNFO Lighting Design MAGGIE FULLILOVE-NUGENT Original Scenic & Costume Design LIZZIE BRACKEN Scenic Design JEFF KMIEC Costume Design BILL MOREY Sound Design MIKE TUTAJ Associate Sound Design ROBERT HORNBOSTEL Original Properties Design MAGGIE FULLILOVE-NUGENT & LIZZIE BRACKEN Properties Master CAITLIN McCARTHY Original Associate Properties Design ARCHER CURRY Technical Direction BEK LAMBRECHT Production Stage Management JUSTINE B. PALMISANO Production Management SAM MORYOUSSEF & ALEX RHYAN Video Production MARTY HIGGENBOTHAM/THE STAGE CHANNEL The following artists significantly contributed to this performance and the play’s creation: Lizzie Bracken (set design, costume design, prop design), Dan Broberg (set design), Maggie Fullilove-Nugent (lighting design), Leah Urzendowski (choreography) & Mike Tutaj (sound design). The original 2011 cast included Anthony Courser, Dean Evans, Molly Plunk, Jay Torrence, Leah Urzendowski & Ryan Walters This performance runs 100 minutes without intermission. Please be aware this play contains flashing lights and some moments that may trigger an adverse reaction with sudden loud noises and sounds of violence. Porchlight Music Theatre acknowledges the generosity of Allstate, the Bayless Family Foundation, DCASE Chicago, the Gaylord and Dorothy Donnelley Foundation, James P.