Download (505Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Star Channels, Jan. 5-11, 2020

JANUARY 5 - 11, 2020 staradvertiser.com HEARING VOICES In an innovative, exciting departure from standard television fare, NBC presents Zoe’s Extraordinary Playlist. Jane Levy stars as the titular character, Zoey Clarke, a computer programmer whose extremely brainy, rigid nature often gets in the way of her ability to make an impression on the people around her. Premiering Tuesday, Jan. 7, on NBC. Delivered over 877,000 hours of programming Celebrating 30 years of empowering our community voices. For our community. For you. olelo.org 590191_MilestoneAds_2.indd 2 12/27/19 5:22 PM ON THE COVER | ZOEY’S EXTRAORDINARY PLAYLIST A penny for your songs ‘Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist’ ...,” narrates the first trailer for the show, “... her new ability, when she witnesses an elabo- what she got, was so much more.” rate, fully choreographed performance of DJ premieres on NBC In an event not unlike your standard super- Khaled’s “All I Do is Win,” but Mo only sees “a hero origin story, an MRI scan gone wrong bunch of mostly white people drinking over- By Sachi Kameishi leaves Zoey with the ability to access people’s priced coffee.” TV Media innermost thoughts and feelings. It’s like she It’s a fun premise for a show, one that in- becomes a mind reader overnight, her desire dulges the typical musical’s over-the-top, per- f you’d told me a few years ago that musicals to fully understand what people want from formative nature as much as it subverts what would be this culturally relevant in 2020, I her seemingly fulfilled. -

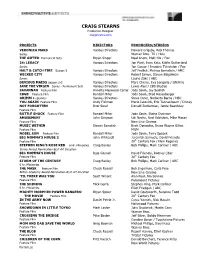

CRAIG STEARNS Production Designer Craigstearns.Com

CRAIG STEARNS Production Designer craigstearns.com PROJECTS DIRECTORS PRODUCERS/STUDIOS VERONICA MARS Various Directors Howard Grigsby, Rob Thomas Series Warner Bros. TV / Hulu THE GIFTED Permanent Sets Bryan Singer Neal Ahern, Matt Nix / Fox 24: LEGACY Various Directors Jon Paré, Evan Katz, Kiefer Sutherland Series Jon Cassar / Imagine Television / Fox HALT & CATCH FIRE Season 3 Various Directors Jeff Freilich, Melissa Bernstein / AMC WICKED CITY Various Directors Robert Simon, Steven Baigelman Series Laurie Zaks / ABC DEVIOUS MAIDS Season 2-3 Various Directors Marc Cherry, Eva Longoria / Lifetime JANE THE VIRGIN Series - Permanent Sets Various Directors Lewis Abel / CBS Studios SAVANNAH Feature Film Annette Haywood-Carter Jody Savin, Jay Sedrish CBGB Feature Film Randall Miller Jody Savin, Brad Rosenberger GRIMM 8 episodes Various Directors Steve Oster, Norberto Barba / NBC YOU AGAIN Feature Film Andy Fickman Mario Iscovich, Eric Tannenbaum / Disney NOT FORGOTTEN Dror Soref Donald Zuckerman, Jamie Beardsley Feature Film BOTTLE SHOCK Feature Film Randall Miller Jody Savin, Elaine Dysinger AMUSEMENT John Simpson Udi Nedivi, Neal Edelstein, Mike Macari Feature Film New Line Cinema MUSIC WITHIN Steven Sawalich Brett Donowho, Bruce Wayne Gillies Feature Film MGM NOBEL SON Feature Film Randall Miller Jody Savin, Terry Spazek BIG MOMMA’S HOUSE 2 John Whitesell Jeremiah Samuels, David Friendly th Feature Film 20 Century Fox / New Regency STEPHEN KING’S ROSE RED 6 Hr. Miniseries Craig Baxley Bob Phillips, Mark Carliner / ABC Emmy Award Nomination-Best Art Direction BIG MOMMA'S HOUSE Raja Gosnell David Friendly, Rodney Liber th Feature Film 20 Century Fox STORM OF THE CENTURY Craig Baxley Bob Phillips, Mark Carliner / ABC 6 hr. -

Use the Force? Understanding Force Majeure Clauses

Use the Force? Understanding Force Majeure Clauses J. Hunter Robinson† J. Christopher Selman†† Whitt Steineker††† Alexander G. Thrasher†††† Introduction It has been said that, sooner or later, everything old is new again.1 In the wake of the novel coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) sweeping the globe in 2020, a heretofore largely overlooked and even less understood nineteenth century legal term has come to the forefront of American jurisprudence: force majeure. Force majeure has become a topic du jour in the COVID-19 world with individuals and companies around the world seeking to excuse non- † B.S. (2011), Auburn University; J.D. (2014), Emory University School of Law. Hunter Robinson is an associate at Bradley Arant Boult Cummings LLP. Hunter is a member of the firm’s litigation and banking and financial services practice groups and represents clients in commercial litigation matters across the country. †† B.S. (2007), Auburn University; J.D. (2012), University of South Carolina School of Law. Chris Selman is a partner at Bradley Arant Boult Cummings LLP. Chris is a members of the firm’s construction and government contracts practice group. He has extensive experience advising clients at every stage of a construction project, managing the resolution of construction disputes domestically and internationally, and drafting and negotiating contracts for a variety of contractor and owner clients. ††† B.A. (2003), University of Alabama; J.D. (2008), Georgetown University Law Center. Whitt Steineker is a partner at Bradley Arant Boult Cummings LLP. Whitt is a member of the firm’s litigation practice group, where he advises clients on a full range of services and routinely represents companies in complex commercial litigation. -

Reading Group Guide

FONT: Anavio regular (wwwUNDER.my nts.com) THE DOME ABOUT THE BOOK IN BRIEF: The idea for this story had its genesis in an unpublished novel titled The Cannibals which was about a group of inhabitants who find themselves trapped in their apartment building. In Under the Dome the story begins on a bright autumn morning, when a small Maine town is suddenly cut off from the rest of the world, and the inhabitants have to fight to survive. As food, electricity and water run short King performs an expert observation of human psychology, exploring how over a hundred characters deal with this terrifying scenario, bringing every one of his creations to three-dimensional life. Stephen King’s longest novel in many years, Under the Dome is a return to the large-scale storytelling of his ever-popular classic The Stand. IN DETAIL: Fast-paced, yet packed full of fascinating detail, the novel begins with a long list of characters, including three ‘dogs of note’ who were in Chester’s Mill on what comes to be known as ‘Dome Day’ — the day when the small Maine town finds itself forcibly isolated from the rest of America by an invisible force field. A woodchuck is chopped right in half; a gardener’s hand is severed at the wrist; a plane explodes with sheets of flame spreading to the ground. No one can get in and no one can get out. One of King’s great talents is his ability to alternate between large set-pieces and intimate moments of human drama, and King gets this balance exactly right in Under the Dome. -

Wednesday Primetime B Grid

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/17/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA: Spotlight PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Cycling Tour of California, Stage 8. (N) Å Hockey 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) IndyCar Racing Indianapolis 500, Qualifying Day 2. NBA Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Enough ›› (2002) 13 MyNet Paid Program Surf’s Up ››› (2007) 18 KSCI Breast Red Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dowdle Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Fresh Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Rick Steves’ Dynamic Europe: Amsterdam Orphans of the Genocide 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Client ››› (1994) 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Hotel Todo Incluido La Madrecita (1973, Comedia) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Charlotte’s Web ››› (2006) Julia Roberts. -

Scary Movies at the Cudahy Family Library

SCARY MOVIES AT THE CUDAHY FAMILY LIBRARY prepared by the staff of the adult services department August, 2004 updated August, 2010 AVP: Alien Vs. Predator - DVD Abandoned - DVD The Abominable Dr. Phibes - VHS, DVD The Addams Family - VHS, DVD Addams Family Values - VHS, DVD Alien Resurrection - VHS Alien 3 - VHS Alien vs. Predator. Requiem - DVD Altered States - VHS American Vampire - DVD An American werewolf in London - VHS, DVD An American Werewolf in Paris - VHS The Amityville Horror - DVD anacondas - DVD Angel Heart - DVD Anna’s Eve - DVD The Ape - DVD The Astronauts Wife - VHS, DVD Attack of the Giant Leeches - VHS, DVD Audrey Rose - VHS Beast from 20,000 Fathoms - DVD Beyond Evil - DVD The Birds - VHS, DVD The Black Cat - VHS Black River - VHS Black X-Mas - DVD Blade - VHS, DVD Blade 2 - VHS Blair Witch Project - VHS, DVD Bless the Child - DVD Blood Bath - DVD Blood Tide - DVD Boogeyman - DVD The Box - DVD Brainwaves - VHS Bram Stoker’s Dracula - VHS, DVD The Brotherhood - VHS Bug - DVD Cabin Fever - DVD Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh - VHS Cape Fear - VHS Carrie - VHS Cat People - VHS The Cell - VHS Children of the Corn - VHS Child’s Play 2 - DVD Child’s Play 3 - DVD Chillers - DVD Chilling Classics, 12 Disc set - DVD Christine - VHS Cloverfield - DVD Collector - DVD Coma - VHS, DVD The Craft - VHS, DVD The Crazies - DVD Crazy as Hell - DVD Creature from the Black Lagoon - VHS Creepshow - DVD Creepshow 3 - DVD The Crimson Rivers - VHS The Crow - DVD The Crow: City of Angels - DVD The Crow: Salvation - VHS Damien, Omen 2 - VHS -

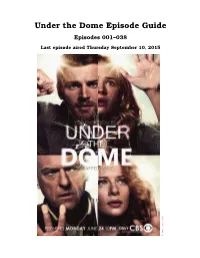

Under the Dome Episode Guide Episodes 001–038

Under the Dome Episode Guide Episodes 001–038 Last episode aired Thursday September 10, 2015 www.cbs.com c c 2015 www.tv.com c 2015 www.cbs.com c 2015 www.tvrage.com The summaries and recaps of all the Under the Dome episodes were downloaded from http://www.tv.com and http: //www.cbs.com and http://www.tvrage.com and processed through a perl program to transform them in a LATEX file, for pretty printing. So, do not blame me for errors in the text ^¨ This booklet was LATEXed on June 28, 2017 by footstep11 with create_eps_guide v0.59 Contents Season 1 1 1 Pilot ...............................................3 2 TheFire.............................................7 3 Manhunt . 11 4 Outbreak . 15 5 Blue on Blue . 19 6 The Endless Thirst . 23 7 Imperfect Circles . 27 8 Thicker Than Water . 31 9 The Fourth Hand . 35 10 Let the Games Begin . 39 11 Speak of the Devil . 43 12 Exigent Circumstances . 47 13 Curtains . 51 Season 2 55 1 Heads Will Roll . 57 2 Infestation . 61 3 Force Majeure . 65 4 Revelation . 69 5 Reconciliation . 73 6 In the Dark . 77 7 Going Home . 81 8 Awakening . 85 9 The Red Door . 89 10 The Fall . 93 11 Black Ice . 97 12 Turn............................................... 101 Season 3 105 1 MoveOn............................................. 107 2 But I’m Not . 111 3 Redux.............................................. 115 4 The Kinship . 119 5 Alaska . 123 6 Caged .............................................. 127 7 Ejecta . 131 8 Breaking Point . 135 9 PlanB.............................................. 139 10 Legacy . 143 11 Love is a Battlefield . 147 12 Incandescence . 151 13 The Enemy Within . -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Alan Sillitoe the LONELINESS of the LONG- DISTANCE RUNNER

Alan Sillitoe THE LONELINESS OF THE LONG- DISTANCE RUNNER Published in 1960 The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner Uncle Ernest Mr. Raynor the School-teacher The Fishing-boat Picture Noah's Ark On Saturday Afternoon The Match The Disgrace of Jim Scarfedale The Decline and Fall of Frankie Buller The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner AS soon as I got to Borstal they made me a long-distance cross-country runner. I suppose they thought I was just the build for it because I was long and skinny for my age (and still am) and in any case I didn't mind it much, to tell you the truth, because running had always been made much of in our family, especially running away from the police. I've always been a good runner, quick and with a big stride as well, the only trouble being that no matter how fast I run, and I did a very fair lick even though I do say so myself, it didn't stop me getting caught by the cops after that bakery job. You might think it a bit rare, having long-distance crosscountry runners in Borstal, thinking that the first thing a long-distance cross-country runner would do when they set him loose at them fields and woods would be to run as far away from the place as he could get on a bellyful of Borstal slumgullion--but you're wrong, and I'll tell you why. The first thing is that them bastards over us aren't as daft as they most of the time look, and for another thing I'm not so daft as I would look if I tried to make a break for it on my longdistance running, because to abscond and then get caught is nothing but a mug's game, and I'm not falling for it. -

COMET Release FINAL

SINCLAIR BROADCAST GROUP AND METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYER ANNOUNCE COMET , FIRST-EVER SCIENCE FICTION MULTI-CHANNEL NETWORK, TO PREMIERE ON OCTOBER 31 st Largest Multicast Network Launch with over 60% of the Country Reaching over 65M Homes (BALTIMORE & LOS ANGELES) October 19, 2015 – Sinclair Television Group, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Sinclair Broadcast Group, Inc. (Nasdaq: SBGI) (“Sinclair”), and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (“MGM ”), announced that COMET, the first-ever 24 hour/7 day per week science fiction multi-channel network, which will feature more than 1,500 hours of premium MGM content, will premiere in over 60% of the country and over 65 million homes on October 31 st of this year. The announcement was made today by David Amy, Chief Operating Officer of Sinclair Broadcast Group, Inc. and John Bryan, President, Domestic Television Distribution, MGM. The network will debut in all top markets including New York, NY; Los Angeles, CA; Chicago, IL; Philadelphia, PA; Seattle, WA; Denver, CO; St. Louis, MO; San Francisco-Oakland-San Jose, CA; Washington D.C.; Boston, MA; Pittsburgh, PA and Houston, TX. In addition to the Sinclair owned television stations, COMET will also launch on a number of Tribune and Titan stations. The network will feature a mix of science fiction, fantasy and adventure fan-favorites from MGM including television series such as “Outer Limits” and “Dead Like Me,” with the blockbusters “Stargate SG-1,” “Stargate Atlantis,” and “Stargate Universe” anchoring the primetime lineup. MGM films will play a crucial role in programming as well, with Moonraker and The Terminator featured during the premiere; Species and Leviathan will also be highlighted throughout the month . -

(Books): Dark Tower (Comics/Graphic

STEPHEN KING BOOKS: 11/22/63: HB, PB, pb, CD Audiobook 1922: PB American Vampire (Comics 1-5): Apt Pupil: PB Bachman Books: HB, pb Bag of Bones: HB, pb Bare Bones: Conversations on Terror with Stephen King: HB Bazaar of Bad Dreams: HB Billy Summers: HB Black House: HB, pb Blaze: (Richard Bachman) HB, pb, CD Audiobook Blockade Billy: HB, CD Audiobook Body: PB Carrie: HB, pb Cell: HB, PB Charlie the Choo-Choo: HB Christine: HB, pb Colorado Kid: pb, CD Audiobook Creepshow: Cujo: HB, pb Cycle of the Werewolf: PB Danse Macabre: HB, PB, pb, CD Audiobook Dark Half: HB, PB, pb Dark Man (Blue or Red Cover): DARK TOWER (BOOKS): Dark Tower I: The Gunslinger: PB, pb Dark Tower II: The Drawing Of Three: PB, pb Dark Tower III: The Waste Lands: PB, pb Dark Tower IV: Wizard & Glass: PB, PB, pb Dark Tower V: The Wolves Of Calla: HB, pb Dark Tower VI: Song Of Susannah: HB, PB, pb, pb, CD Audiobook Dark Tower VII: The Dark Tower: HB, PB, CD Audiobook Dark Tower: The Wind Through The Keyhole: HB, PB DARK TOWER (COMICS/GRAPHIC NOVELS): Dark Tower: The Gunslinger Born Graphic Novel HB, Comics 1-7 of 7 Dark Tower: The Gunslinger Born ‘2nd Printing Variant’ Comic 1 Dark Tower: The Long Road Home: Graphic Novel HB (x2) & Comics 1-5 of 5 Dark Tower: Treachery: Graphic Novel HB, Comics 1–6 of 6 Dark Tower: Treachery: ‘Midnight Opening Variant’ Comic 1 Dark Tower: The Fall of Gilead: Graphic Novel HB Dark Tower: Battle of Jericho Hill: Graphic Novel HB, Comics 2, 3, 5 of 5 Dark Tower: Gunslinger 1 – The Journey Begins: Comics 2 - 5 of 5 Dark Tower: Gunslinger 1 – -

Univerzita Palackého V Olomouci Filozofická Fakulta

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA KATEDRA ANGLISTIKY A AMERIKANISTIKY Veronika Glaserová The Importance and Meaning of the Character of the Writer in Stephen King’s Works Diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Matthew Sweney, Ph.D. Olomouc 2014 Olomouc 2014 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně pod odborným dohledem vedoucího práce a uvedla jsem předepsaným způsobem všechny použité podklady a literaturu. V Olomouci dne Podpis: Poděkování Děkuji vedoucímu práce za odborné vedení práce, poskytování rad a materiálových podkladů k práci. Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 6 1. Genres of Stephen King’s Works ................................................................................. 8 1.1. Fiction .................................................................................................................... 8 1.1.1. Mainstream fiction ........................................................................................... 9 1.1.2. Horror fiction ................................................................................................. 10 1.1.3. Science fiction ............................................................................................... 12 1.1.4. Fantasy ........................................................................................................... 14 1.1.5. Crime fiction .................................................................................................