2 Soeharto's Javanese Pancasila

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indonesia Beyond Reformasi: Necessity and the “De-Centering” of Democracy

INDONESIA BEYOND REFORMASI: NECESSITY AND THE “DE-CENTERING” OF DEMOCRACY Leonard C. Sebastian, Jonathan Chen and Adhi Priamarizki* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION: TRANSITIONAL POLITICS IN INDONESIA ......................................... 2 R II. NECESSITY MAKES STRANGE BEDFELLOWS: THE GLOBAL AND DOMESTIC CONTEXT FOR DEMOCRACY IN INDONESIA .................... 7 R III. NECESSITY-BASED REFORMS ................... 12 R A. What Necessity Inevitably Entailed: Changes to Defining Features of the New Order ............. 12 R 1. Military Reform: From Dual Function (Dwifungsi) to NKRI ......................... 13 R 2. Taming Golkar: From Hegemony to Political Party .......................................... 21 R 3. Decentralizing the Executive and Devolution to the Regions................................. 26 R 4. Necessary Changes and Beyond: A Reflection .31 R IV. NON NECESSITY-BASED REFORMS ............. 32 R A. After Necessity: A Political Tug of War........... 32 R 1. The Evolution of Legislative Elections ........ 33 R 2. The Introduction of Direct Presidential Elections ...................................... 44 R a. The 2004 Direct Presidential Elections . 47 R b. The 2009 Direct Presidential Elections . 48 R 3. The Emergence of Direct Local Elections ..... 50 R V. 2014: A WATERSHED ............................... 55 R * Leonard C. Sebastian is Associate Professor and Coordinator, Indonesia Pro- gramme at the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies, S. Rajaratnam School of In- ternational Studies, Nanyang Technological University, -

Trade-Offs, Compromise and Democratization in a Post-Authoritarian Setting

Asian Social Science; Vol. 8, No. 13; 2012 ISSN 1911-2017 E-ISSN 1911-2025 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Trade-offs, Compromise and Democratization in a Post-authoritarian Setting Paul James Carnegie1 1 Department of International Studies, American University of Sharjah, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates Correspondence: Paul James Carnegie, Department of International Studies, American University of Sharjah, University City, Sharjah 26666, United Arab Emirates. Tel: 971-6-515-4703. E-mail: [email protected] Received: June 17, 2012 Accepted: July 5, 2012 Online Published: October 18, 2012 doi:10.5539/ass.v8n13p71 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ass.v8n13p71 Abstract Reconstituting the disarticulated political space of authoritarian breakdown is anything but straightforward. Distinct trade-offs and ambiguous outcomes are all too familiar. This is in no small part because political change involves compromise with an authoritarian past. The very fact of this transition dynamic leaves us with more questions than answers about the process of democratization. In particular, it is important to ask how we go about interpreting ambiguity in the study of democratization. The following article argues that the way we frame democratization is struggling to come to terms with the ambiguity of contemporary political change. Taking Indonesia as an example, the article maps a tension between authoritarianism and subsequent democratization. The story here is not merely one of opening, breakthrough, and consolidation but also (re-)negotiation. There is also an unfolding at the interstices of culture and politics and of that between discourse and practice. Unfortunately, the insight gained will not lessen some of the more undesirable aspects of Indonesia’s post-authoritarian outcome but it does afford us a more fine-grained reading of the reconfigured patterns of politics that are emerging. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/26/2021 05:50:49AM Via Free Access 96 Marcus Mietzner

Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde Vol. 165, no. 1 (2009), pp. 95–126 URL: http://www.kitlv-journals.nl/index.php/btlv URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-100094 Copyright: content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License ISSN: 0006-2294 MARCUS MIETZNER Political opinion polling in post-authoritarian Indonesia Catalyst or obstacle to democratic consolidation? The introduction of democratic elections in Indonesia after the downfall of Soeharto’s authoritarian New Order regime in 1998 has triggered intensive scholarly debate about the competitiveness, credibility, and representative- ness of these elections. Understandably, discussion has focused mainly on the primary actors in the elections – parties, individual candidates, and voters. In particular, authors have analysed the linkage between leadership, polit- ico-religious cleavages, and voting patterns (Liddle and Mujani 2007), or the extent to which voters are influenced by financial incentives when casting their ballots (Hadiz 2008b). But this concentration on voting behaviour and electoral outcomes has shifted attention away from another development that is at least as significant in shaping Indonesia’s new democracy: the remark- able proliferation of opinion pollsters and political consultants. Ten years after the resignation of long-time autocrat Soeharto, a whole army of advis- ers informs the political elite about the electorate’s expectations, hopes, and demands. Indeed, public opinion polling has acquired such importance that no candidate running for public office can afford to ignore it, and voters have consistently punished those who thought they could. The central role of opinion polls in post-Soeharto politics – and the diver- sity of views expressed in them – have challenged much of the conventional wisdom about the Indonesian electorate. -

Pancasila: Roadblock Or Pathway to Economic Development?

ICAT Working Paper Series February 2015 Pancasila: Roadblock or Pathway to Economic Development? Marcus Marktanner and Maureen Wilson Kennesaw State University www.kennesaw.edu/icat 1. WHAT IS PANCASILA ECONOMICS IN THEORY? When Sukarno (1901-1970) led Indonesia towards independence from the Dutch, he rallied his supporters behind the vision of Pancasila (five principles). And although Sukarno used different wordings on different occasions and ranked the five principles differently in different speeches, Pancasila entered Indonesia’s constitution as follows: (1) Belief in one God, (2) Just and civilized humanity, (3) Indonesian unity, (4) Democracy under the wise guidance of representative consultations, (5) Social justice for all the peoples of Indonesia (Pancasila, 2013). Pancasila is a normative value system. This requires that a Pancasila economic framework must be the means towards the realization of this normative end. McCawley (1982, p. 102) poses the question: “What, precisely, is meant by ‘Pancasila Economics’?” and laments that “[a]s soon as we ask this question, there are difficulties because, as most contributors to the discussion admit, it is all rather vague.” A discussion of the nature of Pancasila economics is therefore as relevant today as it was back then. As far as the history of Pancasila economic thought is concerned, McCawley (1982, p. 103ff.) points at the importance of the writings of Mubyarto (1938-2005) and Boediono (1943-present). Both have stressed five major characteristics of Pancasila economics. These characteristics must be seen in the context of Indonesia as a geographically and socially diverse developing country after independence. They are discussed in the following five sub-sections. -

Political Party Debate on the Presidential Threshold System In

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 418 2nd Annual Civic Education Conference (ACEC 2019) Political Party Debate on the Presidential Threshold System in the Multi-Party Context in Indonesia Putra Kaslin Hutabarat Idrus Affandi Student of Civic Education Department, Professor of Civic Education Department, Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia, Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia, Bandung, Indonesia Bandung, Indonesia Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Abstract- This paper will have political implications in actually related to the party's rational choice in maximizing terms of the implementation of the presidential election system resources to prepare forces ahead of elections [4]. In that is relevant to the style of political parties in Indonesia. practice a democratic consolidation emphasizes the Reviewing the chosen solution for implementing the existence of strong legitimacy targets and solid coalitions so presidential threshold system in the upcoming presidential that all elements including political parties have strong election. This paper was made using descriptive qualitative and using a comparative design. Data collection using interviews, commitments. In other words, democratic consolidation collection and study. The subject of this study was a cadre of requires more than lip service that democracy is in principle the PDI-struggle Party DPP namely Mr. Ir. Edward Tanari, the best governance system, but democracy is also a M.Sc and Head of the Gerindra Party DPP Secretariat namely commitment normative is permitted and reflected Mr. Brigadier General (Purn) Anwar Ende, S.IP. besides this (habituation) in political behavior, both in elite circles, research also took the opinion of political communication organizations, and society as a whole [5]. -

The Professionalisation of the Indonesian Military

The Professionalisation of the Indonesian Military Robertus Anugerah Purwoko Putro A thesis submitted to the University of New South Wales In fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities and Social Sciences July 2012 STATEMENTS Originality Statement I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged. Copyright Statement I hereby grant to the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I retain all property rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. Authenticity Statement I certify that the Library deposit digital copy is a direct equivalent of the final officially approved version of my thesis. -

Contemporary History of Indonesia Between Historical Truth and Group Purpose

Review of European Studies; Vol. 7, No. 12; 2015 ISSN 1918-7173 E-ISSN 1918-7181 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Contemporary History of Indonesia between Historical Truth and Group Purpose Anzar Abdullah1 1 Department of History Education UPRI (Pejuang University of the Republic of Indonesia) in Makassar, South Sulawesi, Indonesia Correspondence: Anzar Abdullah, Department of History Education UPRI (Pejuang University of the Republic of Indonesia) in Makassar, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. E-mail: [email protected] Received: May 28, 2015 Accepted: October 13, 2015 Online Published: November 24, 2015 doi:10.5539/res.v7n12p179 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/res.v7n12p179 Abstract Contemporary history is the very latest history at which the historic event traces are close and still encountered by us at the present day. As a just away event which seems still exists, it becomes controversial about when the historical event is actually called contemporary. Characteristic of contemporary history genre is complexity of an event and its interpretation. For cases in Indonesia, contemporary history usually begins from 1945. It is so because not only all documents, files and other primary sources have not been uncovered and learned by public yet where historical reconstruction can be made in a whole, but also a fact that some historical figures and persons are still alive. This last point summons protracted historical debate when there are some collective or personal memories and political consideration and present power. The historical facts are often provided to please one side, while disagreeable fact is often hidden from other side. -

The Indonesian Presidential Election: Now a Real Horse Race?

Asia Pacific Bulletin EastWestCenter.org/APB Number 266 | June 5, 2014 The Indonesian Presidential Election: Now a Real Horse Race? BY ALPHONSE F. LA PORTA The startling about-face of Indonesia’s second largest political party, Golkar, which is also the legacy political movement of deposed President Suharto, to bolt from a coalition with the front-runner Joko Widodo, or “Jokowi,” to team up with the controversial retired general Prabowo Subianto, raises the possibility that the forthcoming July 9 presidential election will be more than a public crowning of the populist Jokowi. Alphonse F. La Porta, former Golkar, Indonesia’s second largest vote-getter in the April 9 parliamentary election, made President of the US-Indonesia its decision on May 19 based on the calculus by party leaders that Golkar’s role in Society, explains that “With government would better be served by joining with a strong figure like Prabowo rather more forthcoming support from than Widodo, who is a neophyte to leadership on the national level. Thus a large coalition of parties fronted by the authoritarian-minded Prabowo will now be pitted against the the top level of the PDI-P, it is smaller coalition of the nationalist Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P), which had just possible that Jokowi could selected former vice president Jusuf Kalla, nominally of Golkar, as Jokowi’s running mate. achieve the 44 percent plurality If this turn of events sounds complicated, it is—even for Indonesian politics. But first a look some forecast in the presidential at some of the basics: election, but against Prabowo’s rising 28 percent, the election is Indonesia’s fourth general election since Suharto’s downfall in 1998 has marked another increasingly becoming a real— milestone in Indonesia’s democratization journey. -

From Custom to Pancasila and Back to Adat Naples

1 Secularization of religion in Indonesia: From Custom to Pancasila and back to adat Stephen C. Headley (CNRS) [Version 3 Nov., 2008] Introduction: Why would anyone want to promote or accept a move to normalization of religion? Why are village rituals considered superstition while Islam is not? What is dangerous about such cultic diversity? These are the basic questions which we are asking in this paper. After independence in 1949, the standardization of religion in the Republic of Indonesia was animated by a preoccupation with “unity in diversity”. All citizens were to be monotheists, for monotheism reflected more perfectly the unity of the new republic than did the great variety of cosmologies deployed in the animistic cults. Initially the legal term secularization in European countries (i.e., England and France circa 1600-1800) meant confiscations of church property. Only later in sociology of religion did the word secularization come to designate lesser attendance to church services. It also involved a deep shift in the epistemological framework. It redefined what it meant to be a person (Milbank, 1990). Anthropology in societies where religion and the state are separate is very different than an anthropology where the rulers and the religion agree about man’s destiny. This means that in each distinct cultural secularization will take a different form depending on the anthropology conveyed by its historically dominant religion expression. For example, the French republic has no cosmology referring to heaven and earth; its genealogical amnesia concerning the Christian origins of the Merovingian and Carolingian kingdoms is deliberate for, the universality of the values of the republic were to liberate its citizens from public obedience to Catholicism. -

Wayang Golek Menak: Wayang Puppet Show As Visualization Media of Javanese Literature

Wayang Golek Menak: Wayang Puppet Show as Visualization Media of Javanese Literature Trisno Santoso 1 and Bagus Wahyu Setyawan 2 {[email protected] 1, [email protected] 2} 1Institut Seni Indonesia Surakarta, Indonesia 2Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta, Indonesia Abstract. Puppet shows developing in Javanese culture is definitely various, including wayang kulit, wayang kancil, wayang suket, wayang krucil, wayang klithik, and wayang golek. This study was a developmental research, that developed Wayang Golek Ménak Sentolo with using theatre and cinematography approaches. Its aims to develop and create the new form of wayang golek sentolo show, Yogyakarta. The stages included conducting the orientation of wayang golek sentolo show, perfecting the concept, conducting FGD on the development concept, conducting the stage orientation, making wayang puppet protoype, testing the developmental product, and disseminating it in the show. After doing these stages, Wayang Golek Ménak Sentolo show gets developed from the original one, in terms of duration that become shorter, language using other languages than Javanese, show techniques that use theatre approach with modern blocking and lighting, voice acting of wayang figure with using dubbing techniques as in animation films, stage developed into portable to ease the movement as needed, as well as the form of wayang created differently from the original in terms of size and materials used. It is expected that the development and new form of wayang golek menak will get more acceptance from the modern community. Keywords: wayang golek menak, development, puppet show, visualization media, Javanese literature, serat menak. 1. INTRODUCTION Discussing about puppet shows in Java, there are two types of puppet shows, namely wayang golek and wayang krucil . -

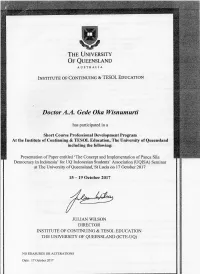

DEMOCRACY of PANCASILA: the CONCEPT and ITS IMPLEMENTATION in INDONESIA By: Dr

DEMOCRACY OF PANCASILA: THE CONCEPT AND ITS IMPLEMENTATION IN INDONESIA By: Dr. Drs. Anak Agung Gede Oka Wisnumurti, M.Si Faculty of Social and Political Science, Warmadewa University, Denpasar-Bali [email protected] Abstract Today democracy is regarded as the most ideal system of government. Many countries declare themselves to be democracies, albeit with different titles. Democracy in general is a system of government in which sovereignty is in the hands of the people, or is universally said to be government from, by and for the people. In Indonesia the democratic system used is the democracy of Pancasila. Democracy is based on the personality and philosophy of life of the Indonesian nation. Democracy based on Pancasila values, namely; based on the democracy led by the wisdom in the deliberations / representatives, having the concept of one god almighty upholding a just and civilized humanity, to unite Indonesia to bring about social justice for all Indonesians. The basic principle, prioritizing deliberation, with deliberations is expected to satisfy all those who differ, an expectation that is very difficult can be realized in the practice of nation and state. Implementation of Democrazy of Pancasila in the course of the nation's history, often experienced ups and downs. The applied democracy tends to deviate from the basic concept of the state, such as libral, guided, parliamentary and authoritarian practices. The 1998 reform order became the cornerstone of the democratic movement in Indonesia. The transition to a democratic system of government. If the implementation of this Pancasila democracy system can be realized, then Indonesia can be a model in the application of democratic system in governance. -

'Warring Words'

‘Warring Words’: Students and the state in New Order Indonesia, 1966-1998 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Australian National University. Elisabeth Jackson Southeast Asia Centre Faculty of Asian Studies June 2005 CERTIFICATION I, Elisabeth Jackson, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy at the Australian National University, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. It has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. …………………………. Elisabeth Jackson 3 June 2005 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I have been incredibly fortunate to have the support of a great many wonderful people throughout the course of researching and writing this thesis. First and foremost, I would like to thank Virginia Hooker for her enthusiasm for this project and her faith in my ability to do it. Her thoughtful criticisms gently steered me in the right direction and made it possible for me to see the bigger picture. I also owe enormous thanks to Ed Aspinall, who encouraged me to tackle this project in the first place and supported me throughout my candidature. He was also an invaluable source of expertise on student activism and the politics of the New Order and his extensive comments on my drafts enabled me to push my ideas further. Virginia and Ed also provided me with opportunities to try my hand at teaching. Tim Hassall’s considered comments on the linguistic aspects of this thesis challenged me to think in new ways about Indonesian language and helped to strengthen the thesis considerably.