The Mass Impact of Videogame Technology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

708 Game List (Vertical Monitor)

708 Game List (Vertical Monitor) - 1. 10-Yard Fight (Japan) 2. 1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) 3. 1942 (set 1) 4. 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 5. 1943: The Battle of Midway (US) 6. 1945k III 7. 19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) 8. 4 Fun in 1 9. 4 Player Bowling Alley 10. 600 11. '99: The Last War 12. Abscam 13. Action Fighter 14. Aero Fighters 15. Agent Super Bond (Super Cobra conversion) 16. Air Gallet 17. Ali Baba and 40 Thieves 18. All American Football (rev D 19. Alley Master 20. Alpha Mission 21. Alpine Ski (set 1) 22. American Horseshoes (US) 23. Amidar 24. Angel Kids (Japan) 25. Anteater 26. APB - All Points Bulletin (rev 7) 27. Apocaljpse Now 28. Arabian 29. Arbalester 30. Argus 31. Arkanoid - Revenge of DOH (World) 32. Arkanoid (World) 33. Armed Formation 34. Armored Car (set 1) 35. ASO - Armored Scrum Object 36. Assault 37. Astro Blaster (version 3) 38. Astro Invader 39. Atari Mini Golf (prototype) 40. Avengers (US set 1) 41. Azurian Attack 42. Bagman 43. Balloon Bomber 44. Baluba-louk no Densetsu 45. Bandido 46. Batsugun (set 1) 47. Battlantis 48. Battle Cruiser M-12 49. Battle Field (Japan) 50. Battle Lane! Vol. 5 (set 1) 51. Battle of Atlantis (set 1) 52. Battle Wings 53. Beastie Feastie 54. Bee Storm - DoDonPachi II (V102 55. Beezer (set 1) 56. Bermuda Triangle (Japan) 57. Big Event Golf 58. Big Kong 59. Bio Attack 60. Birdie King 2 61. Birdie King 3 62. Birdie King 63. Birdie Try (Japan) 64. -

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games ( Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack ( Arcade, TG16) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1943: Kai (TG16) 12. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 13. 1944: The Loop Master ( Arcade) 14. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 15. 19XX: The War Against Destiny ( Arcade) 16. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge ( Arcade) 17. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 18. 2020 Super Baseball ( Arcade, SNES) 19. 21-Emon (TG16) 20. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 21. 3 Count Bout ( Arcade) 22. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 23. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 24. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 25. 3-D WorldRunner (NES) 26. 3D Asteroids (Atari 7800) 27. -

STERN RELEASES Big Buck Hunter® PRO PINBALL to MUCH ACCLAIM

PRESS RELEASE STERN RELEASES Big Buck Hunter® PRO PINBALL TO MUCH ACCLAIM January 13, 2010--Big Buck Hunter® PRO Pinball by Stern Pinball, Inc. is a hunting game that delivers a hot new quarry of no-limit fun to players everywhere. Big Buck Hunter® PRO Pinball is based on the hugely successful Big Buck Hunter® Arcade Video Game series by Raw Thrills, Inc. and Play Mechanix, Inc. Eugene Jarvis, George Petro, and Mark Ritchie of Raw Thrills/Play Mechanix assisted the staff at Stern Pinball with the design of Big Buck Hunter® PRO Pinball. And like the arcade video games, Big Buck Hunter® PRO Pinball is sure to challenge new hunters, as well as seasoned marksmen. Big Buck Hunter® PRO Pinball takes you on a hunting adventure. Players are in pursuit of wild game. The game features a motorized buck that runs across a forest-like playfield. Strike the buck multiple times and start Big Buck Multiball. Big Buck Hunter® PRO Pinball also features a ramp that winds around the playfield, a ram that kicks the ball back to the player, an elk mechanism that re-directs the pinball, and lots of multiball action. Big Buck Hunter® PRO Pinball features speech from the video game. George Petro, narrator of the Big Buck Hunter® Arcade Video Game series narrates the Pinball machine while contributing additional original speech. Pappy, voiced by Scott Pikulski, also appears offering comic relief. John Youssi, creator of the Big Buck Hunter® Arcade Video Game art, contributes the art for the pinball. Big Buck Hunter® PRO Pinball also features sounds and music by Ken Hale, the sound engineer for the Big Buck Hunter® Arcade Video Games. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

List of Intellivision Games

List of Intellivision Games 1) 4-Tris 25) Checkers 2) ABPA Backgammon 26) Chip Shot: Super Pro Golf 3) ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS 27) Commando Cartridge 28) Congo Bongo 4) ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS 29) Crazy Clones Treasure of Tarmin Cartridge 30) Deep Pockets: Super Pro Pool and Billiards 5) Adventure (AD&D - Cloudy Mountain) (1982) (Mattel) 31) Defender 6) Air Strike 32) Demon Attack 7) Armor Battle 33) Diner 8) Astrosmash 34) Donkey Kong 9) Atlantis 35) Donkey Kong Junior 10) Auto Racing 36) Dracula 11) B-17 Bomber 37) Dragonfire 12) Beamrider 38) Eggs 'n' Eyes 13) Beauty & the Beast 39) Fathom 14) Blockade Runner 40) Frog Bog 15) Body Slam! Super Pro Wrestling 41) Frogger 16) Bomb Squad 42) Game Factory 17) Boxing 43) Go for the Gold 18) Brickout! 44) Grid Shock 19) Bump 'n' Jump 45) Happy Trails 20) BurgerTime 46) Hard Hat 21) Buzz Bombers 47) Horse Racing 22) Carnival 48) Hover Force 23) Centipede 49) Hypnotic Lights 24) Championship Tennis 50) Ice Trek 51) King of the Mountain 52) Kool-Aid Man 80) Number Jumble 53) Lady Bug 81) PBA Bowling 54) Land Battle 82) PGA Golf 55) Las Vegas Poker & Blackjack 83) Pinball 56) Las Vegas Roulette 84) Pitfall! 57) League of Light 85) Pole Position 58) Learning Fun I 86) Pong 59) Learning Fun II 87) Popeye 60) Lock 'N' Chase 88) Q*bert 61) Loco-Motion 89) Reversi 62) Magic Carousel 90) River Raid 63) Major League Baseball 91) Royal Dealer 64) Masters of the Universe: The Power of He- 92) Safecracker Man 93) Scooby Doo's Maze Chase 65) Melody Blaster 94) Sea Battle 66) Microsurgeon 95) Sewer Sam 67) Mind Strike 96) Shark! Shark! 68) Minotaur (1981) (Mattel) 97) Sharp Shot 69) Mission-X 98) Slam Dunk: Super Pro Basketball 70) Motocross 99) Slap Shot: Super Pro Hockey 71) Mountain Madness: Super Pro Skiing 100) Snafu 72) Mouse Trap 101) Space Armada 73) Mr. -

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games (Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack (TG16, Arcade) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1942 (Revision B) (Arcade) 12. 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) (Arcade) 13. 1943: Kai (TG16) 14. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 15. 1944: The Loop Master (Arcade) 16. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 17. 19XX: The War Against Destiny (Arcade) 18. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge (Arcade) 19. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 20. 2020 Super Baseball (SNES, Arcade) 21. 21-Emon (TG16) 22. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 23. 3 Count Bout (Arcade) 24. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 25. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 26. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 27. -

Arcade-Style Game Design: Postwar Pinball and The

ARCADE-STYLE GAME DESIGN: POSTWAR PINBALL AND THE GOLDEN AGE OF COIN-OP VIDEOGAMES A Thesis Presented to The Academic Faculty by Christopher Lee DeLeon In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Digital Media in the School of Literature, Communication and Culture Georgia Institute of Technology May 2012 ARCADE-STYLE GAME DESIGN: POSTWAR PINBALL AND THE GOLDEN AGE OF COIN-OP VIDEOGAMES Approved by: Dr. Ian Bogost, Advisor Dr. John Sharp School of LCC School of LCC Georgia Institute of Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Brian Magerko Steve Swink School of LCC Creative Director Georgia Institute of Technology Enemy Airship Dr. Celia Pearce School of LCC Georgia Institute of Technology Date Approved: March 27, 2012 In memory of Eric Gary Frazer, 1984–2001. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank: Danyell Brookbank, for companionship and patience in our transition to Atlanta. Ian Bogost, John Sharp, Brian Magerko, Celia Pearce, and Steve Swink for ongoing advice, feedback, and support as members of my thesis committee. Andrew Quitmeyer, for immediately encouraging my budding pinball obsession. Michael Nitsche and Patrick Coursey, for also getting high scores on Arnie. Steve Riesenberger, Michael Licht, and Tim Ford for encouragement at EALA. Curt Bererton, Mathilde Pignol, Dave Hershberger, and Josh Wagner for support and patience at ZipZapPlay. John Nesky, for his assistance, talent, and inspiration over the years. Lou Fasulo, for his encouragement and friendship at Sonic Boom and Z2Live. Michael Lewis, Harmon Pollock, and Tina Ziemek for help at Stupid Fun Club. Steven L. Kent, for writing the pinball chapter in his book that inspired this thesis. -

Newagearcade.Com 5000 in One Arcade Game List!

Newagearcade.com 5,000 In One arcade game list! 1. AAE|Armor Attack 2. AAE|Asteroids Deluxe 3. AAE|Asteroids 4. AAE|Barrier 5. AAE|Boxing Bugs 6. AAE|Black Widow 7. AAE|Battle Zone 8. AAE|Demon 9. AAE|Eliminator 10. AAE|Gravitar 11. AAE|Lunar Lander 12. AAE|Lunar Battle 13. AAE|Meteorites 14. AAE|Major Havoc 15. AAE|Omega Race 16. AAE|Quantum 17. AAE|Red Baron 18. AAE|Ripoff 19. AAE|Solar Quest 20. AAE|Space Duel 21. AAE|Space Wars 22. AAE|Space Fury 23. AAE|Speed Freak 24. AAE|Star Castle 25. AAE|Star Hawk 26. AAE|Star Trek 27. AAE|Star Wars 28. AAE|Sundance 29. AAE|Tac/Scan 30. AAE|Tailgunner 31. AAE|Tempest 32. AAE|Warrior 33. AAE|Vector Breakout 34. AAE|Vortex 35. AAE|War of the Worlds 36. AAE|Zektor 37. Classic Arcades|'88 Games 38. Classic Arcades|1 on 1 Government (Japan) 39. Classic Arcades|10-Yard Fight (World, set 1) 40. Classic Arcades|1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) 41. Classic Arcades|18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) 42. Classic Arcades|1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) 43. Classic Arcades|1942 (Revision B) 44. Classic Arcades|1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 45. Classic Arcades|1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) 46. Classic Arcades|1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) 47. Classic Arcades|1945k III 48. Classic Arcades|19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) 49. Classic Arcades|2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 50. Classic Arcades|2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 51. -

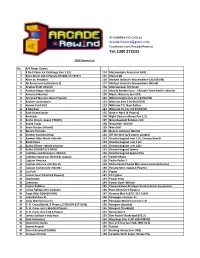

Arcade Rewind 3500 Games List 190818.Xlsx

ArcadeRewind.com.au [email protected] Facebook.com/ArcadeRewind Tel: 1300 272233 3500 Games List No. 3/4 Player Games 1 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 114 Metamorphic Force (ver EAA) 2 Alien Storm (US,3 Players,FD1094 317-0147) 115 Mexico 86 3 Alien vs. Predator 116 Michael Jackson's Moonwalker (US,FD1094) 4 All American Football (rev E) 117 Michael Jackson's Moonwalker (World) 5 Arabian Fight (World) 118 Minesweeper (4-Player) 6 Arabian Magic <World> 119 Muscle Bomber Duo - Ultimate Team Battle <World> 7 Armored Warriors 120 Mystic Warriors (ver EAA) 8 Armored Warriors (Euro Phoenix) 121 NBA Hangtime (rev L1.1 04/16/96) 9 Asylum <prototype> 122 NBA Jam (rev 3.01 04/07/93) 10 Atomic Punk (US) 123 NBA Jam T.E. Nani Edition 11 B.Rap Boys 124 NBA Jam TE (rev 4.0 03/23/94) 12 Back Street Soccer 125 Neck-n-Neck (4 Players) 13 Barricade 126 Night Slashers (Korea Rev 1.3) 14 Battle Circuit <Japan 970319> 127 Ninja Baseball Batman <US> 15 Battle Toads 128 Ninja Kids <World> 16 Beast Busters (World) 129 Nitro Ball 17 Blazing Tornado 130 Numan Athletics (World) 18 Bomber Lord (bootleg) 131 Off the Wall (2/3-player upright) 19 Bomber Man World <World> 132 Oriental Legend <ver.112, Chinese Board> 20 Brute Force 133 Oriental Legend <ver.112> 21 Bucky O'Hare <World version> 134 Oriental Legend <ver.126> 22 Bullet (FD1094 317-0041) 135 Oriental Legend Special 23 Cadillacs and Dinosaurs <World> 136 Oriental Legend Special Plus 24 Cadillacs Kyouryuu-Shinseiki <Japan> 137 Paddle Mania 25 Captain America 138 Pasha Pasha 2 26 Captain America -

412 Game List

412 Game List 1941 - Counter Attack (351) Gang Busters (286) PuckMan (022) 1943 Kai (068) Gaplus (073) PuckMan (speedup) (023) 1945 Kai III (398) Gardia (128) Q*bert (370) 19XX:The War Against Destiny (384) Gemini Wing (301) Q*bert's Qubes (371) 800 Fathoms (160) Ghostmuncher Galaxian (129) Qix (372) 1942 (029) Gigas (245) Qix 2 (373) 1943 (056) Go Go Mr. Yamaguchi (130) Quester (308) Abscam (075) Gomoku Narabe Renju (188) Rafflesia (209) Aero Fighters (278) Gorf (396) Raiden (412) Air Duel (305) Gorkans (131) Rally Bike (285) Ajax (076) Green Beret (358) Regulus (210) Ali Baba and 40 Thieves (077) Grobda (132) Return of the Invaders (019) Alley Master (339) Guerrilla War (359) Ring King (374) Alpine Ski (352) Gun & Frontier (318) Road Fighter (211) Amidar (061) Gun Dealer (133) Roc'n Rope (212) Anteater (271) Gun.Smoke (066) Rompers (343) APB - All Points Bulletin (353) Guwange (407) Round-Up (213) Arabian (079) Guzzler (134) Rug Rats (214) Arbalester (397) Gyrodine (135) S.R.D.S.R.D. S.R.D. Mission (215) Argus (290) Gyruss (027) Samurai Nihon-ichi (217) Arkanoid - Revenge of DOH (395) Hangly-Man (136) SAR - Search And Rescue (331) Arkanoid (044) Hero in the Castle of Doom (137) Satan of Saturn (218) Armed Formation (298) High Way Race (138) Satan's Hollow (375) Armored Car (080) Hoccer (139) Saturn (219) Ashura Blaster (316) Hopper Robo (140) Scramble (051) Assault (327) Ikari Warriors (315) Scrambled Egg (221) Astro Blaster (081) Image Fight (291) Seicross (226) Astro Fighter (082) Intrepid (141) Senjyo (222) Astro Invader (083) Jack the Giantkiller (142) Shao-Lin's Road (054) Bagman (220) Jackal (187) Shot Rider (223) Battlantis (323) Joinem (143) Sindbad Mystery (224) Battle Bakraid (408) Jolly Jogger (144) Sinistar (376) Battle Lane! (084) Journey(1P) (360) Sky Base (225) Battle-Road, The (085) Joust 2 (361) Sky Fox (330) Beastie Feastie (086) Joyman (145) Sky Soldiers (302) Bells & Whistles (349) Jr. -

List of Pre-Loaded Games

List of Pre-loaded Games. CAPCOM Classics Collection: 1942, 1943, Commando, Gunsmoke, Street Fighter I, Street Fighter II NAMCO Museum: Bosconian, Dig Dug, Dragon Spirit, Galaga, Galaxian, Mappy, Ms. Pac-Man, Pac-Man, Pole Position, Pole Position II, Rally X, Rolling Thunder, Sky Kid, Xevious TAITO Legends: Alpine Ski, Arabian Magic, Battle Shark, Bonze Adventure, Bubble Bobble, Bubble Symphony, Cadash, Cameltry, Chack ‘n Pop, Cleopatra Fortune, Colony 7, Continental Circus, Crazy Balloon, Darius Gaiden, Don Doko Don, Dungeon Magic, Electric Yo-Yo, Elevator Action, Elevator Action II, Exzisus, Football Champ, Front Line, Galactic Attack, Gekirindan, Gladiator, Great Swordsman, Grid Seeker, Growl, Gun & Frontier, Insektor X, Jungle Hunt, Kiki Kaikai, Kuri Kinton, Liquid Kids, Lunar Rescue, Metal Black, Nastar, Op Thunderbolt, Operation Wolf, Phoenix, Plotting, Plump Pop, Pop’n Pop, Puchi Carat, Puzzle Bobble 2, Qix, Raimais, Rainbow Islands, Rastan, Return of the Invaders, Space Gun, Space Invaders, Space Invaders ’91, Space Invaders ’95, Space Invaders DX, Space Invaders Pt 2, Super Qix, The Fairyland Story, The Legend of Kage, The New Zealand Story, The Ninja Kids, Thunderfox, Tokio, Tube It, Violence Fight, Volfied, Wild Western, Zoo Keeper MIDWAY Arcade Treasures: 720, A.P.B., Arch Rivals, Badlands, Blaster, Bubbles, Championship Sprint, Cyberball 2072, Defender, Defender 2: Stargate, Gauntlet, Gauntlet 2, Hard Drivin', Hydro Thunder, Joust, Joust 2, Klax, Kozmik Krooz'r, Marble Madness, Mortal Kombat 2, Mortal Kombat 3, NARC, Off -

Download 80 PLUS 4983 Horizontal Game List

4 player + 4983 Horizontal 10-Yard Fight (Japan) advmame 2P 10-Yard Fight (USA, Europe) nintendo 1941 - Counter Attack (Japan) supergrafx 1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) mame172 2P sim 1942 (Japan, USA) nintendo 1942 (set 1) advmame 2P alt 1943 Kai (Japan) pcengine 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) mame172 2P sim 1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) mame172 2P sim 1943 - The Battle of Midway (USA) nintendo 1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) mame172 2P sim 1945k III advmame 2P sim 19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) mame172 2P sim 2010 - The Graphic Action Game (USA, Europe) colecovision 2020 Super Baseball (set 1) fba 2P sim 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) mame078 4P sim 36 Great Holes Starring Fred Couples (JU) (32X) [!] sega32x 3 Count Bout / Fire Suplex (NGM-043)(NGH-043) fba 2P sim 3D Crazy Coaster vectrex 3D Mine Storm vectrex 3D Narrow Escape vectrex 3-D WorldRunner (USA) nintendo 3 Ninjas Kick Back (U) [!] megadrive 3 Ninjas Kick Back (U) supernintendo 4-D Warriors advmame 2P alt 4 Fun in 1 advmame 2P alt 4 Player Bowling Alley advmame 4P alt 600 advmame 2P alt 64th. Street - A Detective Story (World) advmame 2P sim 688 Attack Sub (UE) [!] megadrive 720 Degrees (rev 4) advmame 2P alt 720 Degrees (USA) nintendo 7th Saga supernintendo 800 Fathoms mame172 2P alt '88 Games mame172 4P alt / 2P sim 8 Eyes (USA) nintendo '99: The Last War advmame 2P alt AAAHH!!! Real Monsters (E) [!] supernintendo AAAHH!!! Real Monsters (UE) [!] megadrive Abadox - The Deadly Inner War (USA) nintendo A.B.