Central African Republic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When Peace Is Not Peaceful : Violence Against Women in the Central African Republic

The programme ‘Empowering Women for Sustainable Development’ of the European Union in the Central African Republic When Peace is not Peaceful : Violence against Women in the Central African Republic Results of a Baseline Study on Perceptions and Rates of Incidence of Violence against Women This project is financed by the The project is implemented by Mercy European Union Corps in partnership with the Central African Women’s Organisation When Peace is not Peaceful: Violence Against Women in the Central African Republic Report of results from a baseline study on perceptions of women’s rights and incidence of violence against women — Executive Summary — Mercy Corps Central African Republic is currently implementing a two-year project funded by the European Commission, in partnership with the Organization of Central African Women, to empower women to become active participants in the country’s development. The program has the following objectives: to build the capacities of local women’s associations to contribute to their own development and to become active members of civil society; and to raise awareness amongst both men and women of laws protecting women’s rights and to change attitudes regarding violence against women. The project is being conducted in the four zones of Bangui, Bouar, Bambari and Bangassou. For many women in the Central African Republic, violence is a reality of daily life. In recent years, much attention has been focused on the humanitarian crisis in the north, where a February 2007 study conducted by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs highlighted the horrific problem of violence against women in conflict-affected areas, finding that 15% of women had been victims of sexual violence. -

Iom Regional Response

IOM REGIONAL RESPONSE SITUATION REPORT │ 9 - 22 June 2015 IOM providing health care assistance to returnees in Gaoui. (Photo: IOM Chad) SITUATION OVERVIEW Central African Republic (CAR): Throughout the country, the general situation has remained calm over the course of the reporting period. On 22 June, the National Elections Authority (ANE) of CAR announced the electoral calendar marking the timeline for return of the country to its pre-conflict constitutional order. As per the ANE calendar, the Constitutional Referendum is CAR: IOM handed over six rehabilitated classrooms at the scheduled to take place on 4 October, and the first round of Lycee Moderne de Bouar in western CAR. Parliamentary and Presidential Elections on 18 October 2015. However, concern remains over the feasibility of the plan due to the limited time left for voter registration, especially considering the large number of IDP and refugees. CHAD: IOM completed the construction of 300 emergency Currently, there are 399,268 Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in shelters that will accommodate 413 returnees hosted in CAR, including 33,067 people in Bangui and Bimbo (Source: Kobiteye and Danamadja temporary sites. Commission for Population Movement). CAMEROON: On 18 June, IOM’s team in Garoua Boulai distributed WFP food parcels to 56 households (368 CAMP COORDINATION AND CAMP MANAGEMENT Under the CCCM/NFI/Shelter Cluster and in coordination with individuals). UNHCR, WFP, the Red Cross, World Vision, and PU-AMI, IOM continues the voluntary return of IDPs from the Mpoko displacement site. As of 22 June, 2,872 IDP households have been deregistered from the Mpoko displacement site, of which 2,373 participated in the “My Peace Hat” workshop at Nasradine School, have been registered in their district of return. -

In Their Own Hands CRS 2030 STRATEGY VIETNAM Photo by Lisa Murray for CRS

In Their Own Hands CRS 2030 STRATEGY VIETNAM Photo by Lisa Murray for CRS ‘Solidarity ... is not a feeling of vague compassion or shallow distress at the misfortunes of so many people, both near and far. It is a firm and persevering determination to commit oneself to the common good … to the good of all and of each individual.’ SOLLICITUDO REI SOCIALIS #38 2 CRS VISION 2030 STRATEGY A Message From Our President & CEO At Catholic Relief Services, we are dedicated to putting our faith into action to do whatever it takes to build a world in which all people reach their full human potential in the context of just and peaceful societies. We have a vision for a world that respects the sacredness and dignity of the human person and the integrity of all of God’s creation. Our mission is a faith-filled call to serve others—based on need, not creed, race or nationality—as taught in the Gospel of Jesus Christ, prioritizing the most vulnerable and marginalized among us. I am proud of CRS’ 75 years of global solidarity and service to our sisters and brothers around the world. From responding to the humanitarian needs of migrants and refugees during World War II to programs and services that today reach over 130 million people across 110 countries, our enduring mission inspires and guides us. In our new strategy, we look to the evolving needs and opportunities of the people we serve and their local institutions, and challenge ourselves to be bolder and more ambitious in our aspirations to not only catalyze transformational change to combat poverty, injustice and violence, but to achieve these results at greater scale. -

MINUSCA Aoukal S U D a N

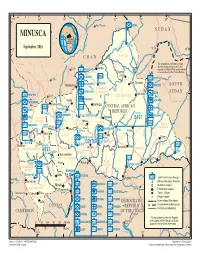

14 ° 16 ° 18 ° 20 ° 22 ° 24 ° 26 ° Am Timan ZAMBIA é MINUSCA Aoukal S U D A N t CENTRAL a lou AFRICAN m B u a REPUBLIC a O l h r a r Birao S h e September 2016 a l r B Al Fifi 'A 10 h r 10 ° ° a a B b C h VAKAGAVAVAKAKAGA a r C H A D i The boundaries and names shown Garba and the designations used on this Sarh HQ Sector Center map do not imply official endorsement ouk ahr A Ouanda or acceptance by the United Nations. B Djallé PAKISTAN UNPOL Doba HQ Sector East Sam Ouandja BANGLADESH Ndélé K S O U T H Maïkouma o MOROCCO t BAMINGUIBAMBAMINAMINAMINGUINGUIGUI t o BANGLADESH BANGORANBABANGBANGORNGORNGORANORAN S U D A N BENIN 8° Sector West Kaouadja 8° HQ Goré HAUTE-KOTTOHAHAUTHAUTE-HAUTE-KOUTE-KOE-KOTTKOTTO i u a g PAKISTAN n Kabo i CAMBODIA n i n i V BANGLADESH i u b b g i Markounda i Bamingui n r UNPOL r UNPOL i CENTRAL AFRICAN G G RWANDA Batangafo m NIGER a REPUBLIC Paoua B Sector CAMEROON Kaga Bandoro SRI LANKA PERU OUHAMOUOUHAHAM Yangalia EAST m NANANA -P-PEN-PENDÉENDÉ a Mbrès OUAKOUOUAKAAKA UNPOL h u GRGRÉBGRÉBIZGRÉBIZIÉBIZI UNPOL HAUT-HAHAUTUT- FPU CAMEROON 1 Bossangoa O ka MBOMOUMBMBOMOMOU a MAURITANIA o Bouca u Dékoa Bria Yalinga k Dékoa n O UNPOL i Bozoum OUHAMOUOUHAHAM h Ippy C Sector UNPOL i Djéma 6 BURUNDI r 6 ° a ° Bambari b Bouar CENTER rra Baoro M Oua UNPOL Baboua Baoro Sector Sibut NANA-MAMBÉRÉNANANANANA-MNA-MNA-MAM-MAMBÉAMBÉAMBÉRÉBÉRÉ Grimari Bakouma MBOMOUMBMBOMOMOU M WEST Obo a Yaloke KÉMKKÉMOÉMO m Bossembélé M b angúi bo er OMOMBEOMBELLOMBELLA-MPOKOBELLA-BELLYalokeYaloYaLLA-MPLLA-lokeA-MPOKA-MPMPOKOOKO ub UNPOL mo e O -

Central African Republic Humanitarian Situation Report

Central African Republic Humanitarian Situation Report © UNICEFCAR/2018/Matous February 2019 SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights 28 February 2019 1.5 million - On 6 February the Central African Republic (CAR) government and # of children in need of humanitarian assistance 14 of the country’s armed groups signed a new peace agreement in 2.9 million Khartoum (Sudan). The security and humanitarian situation still # of people in need remained volatile, with the Rapid Response Mechanism recording 11 (OCHA, December 2018) new conflict-related alerts; 640,969 # of Internally displaced persons - In February, UNICEF and partners ensured provision of quality (CMP, December 2018) primary education to 52,987 new crisis-affected children (47% girls) Outside CAR admitted into 95 temporary learning spaces across the country; - 576,926 - In a complex emergency context, from 28 January to 16 February, # of registered CAR refugees UNICEF carried out a needs assessment and provided first response (UNHCR, December 2018) in WASH and child protection on the Bangassou-Bakouma and Bangassou-Rafaï axes in the remote Southeast 2018 UNICEF Appeal US$ 59 million - In Kaga-Bandoro, three accidental fires broke out in three IDP sites, Funding status* ($US) leaving 4,620 people homeless and 31 injured. UNICEF responded to the WASH and Education needs UNICEF’s Response with Partners Funds received: Sector/Cluster UNICEF $2,503,596 Key Programme Indicators Cluster Cumulative UNICEF Cumulative Target results (#) Target results (#) Carry-Over: $11,958,985 WASH: Crisis-affected people with access to safe water for drinking, 800,000 188,705 400,000 85,855 cooking and personal hygiene Education: Children (boys and girls 3-17yrs) attending school in a class 600,000 42,360 442,500 42,360 Funding Gap: led by a teacher trained in 44,537,419 psychosocial support $ Health: People and children under 5 in IDP sites and enclaves with access N/A 82,068 7,806 to essential health services and medicines. -

Central African Republic Emergency Update #2

Central African Republic Emergency Update #2 Period Covered 18-24 December 2013 [1] Highlights There are currently some 639,000 internally displaced people in the Central African Republic (CAR), including more than 210,000 in Bangui in over 40 sites. UNHCR submitted a request to the Humanitarian Coordinator for the activation of the Camp Coordination and Camp Management Cluster. Since 14 December, UNHCR has deployed twelve additional staff to Bangui to support UNHCR’s response to the current IDP crisis. Some 1,200 families living at Mont Carmel, airport and FOMAC/Lazaristes Sites were provided with covers, sleeping mats, plastic sheeting, mosquito domes and jerrycans. About 50 tents were set up at the Archbishop/Saint Paul Site and Boy Rabe Monastery. From 19 December to 20 December, UNHCR together with its partners UNICEF and ICRC conducted a rapid multi- sectoral assessment in IDP sites in Bangui. Following the declaration of the L3 Emergency, UNHCR and its partners have started conducting a Multi- Cluster/Sector Initial Rapid Assessment (MIRA) in Bangui and the northwest region. [2] Overview of the Operation Population Displacement 2013 Funding for the Operation Funded (42%) Funding Gap (58%) Total 2013 Requirements: USD 23.6M Partners Government agencies, 22 NGOs, FAO, BINUCA, OCHA, UNAIDS, UNDP, UNFPA, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. For further information, please contact: Laroze Barrit Sébastien, Phone: 0041-79 818 80 39, E-mail: [email protected] Central African Republic Emergency Update #2 [2] Major Developments Timeline of the current -

PGRN-M-F-PGES.Pdf

RÉPUBLIQUE CENTRAFRICAINE Public Disclosure Authorized Unité-Dignité-Travail Public Disclosure Authorized Projet de Gouvernance des Ressources Naturelles (PGRN) pour les secteurs forestiers et miniers de la République Centrafricaine Public Disclosure Authorized Cadre de Gestion Environnementale et Sociale (CGES) RAPPORT FINAL Public Disclosure Authorized Décembre 2018 CGES du PGRN des secteurs forestiers et miniers de la République Centrafricaine Sommaire TABLE DES MATIERES ACRONYMES .......................................................................................................................... 11 RESUME EXECUTIF ............................................................................................................... 13 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................... 39 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 53 1.1. CONTEXTE ................................................................................................................ 53 1.1.1. Contexte Politique ................................................................................................ 53 1.1.2. Contexte Social .................................................................................................... 53 1.1.3. Contexte économique .......................................................................................... 53 1.2. CONTEXTE DE LA REALISATION DU CGES .......................................................... -

THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC and Small Arms Survey by Eric G

SMALL ARMS: A REGIONAL TINDERBOX A REGIONAL ARMS: SMALL AND REPUBLIC AFRICAN THE CENTRAL Small Arms Survey By Eric G. Berman with Louisa N. Lombard Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies 47 Avenue Blanc, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland p +41 22 908 5777 f +41 22 732 2738 e [email protected] w www.smallarmssurvey.org THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC AND SMALL ARMS A REGIONAL TINDERBOX ‘ The Central African Republic and Small Arms is the most thorough and carefully researched G. Eric By Berman with Louisa N. Lombard report on the volume, origins, and distribution of small arms in any African state. But it goes beyond the focus on small arms. It also provides a much-needed backdrop to the complicated political convulsions that have transformed CAR into a regional tinderbox. There is no better source for anyone interested in putting the ongoing crisis in its proper context.’ —Dr René Lemarchand Emeritus Professor, University of Florida and author of The Dynamics of Violence in Central Africa ’The Central African Republic, surrounded by warring parties in Sudan, Chad, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, lies on the fault line between the international community’s commitment to disarmament and the tendency for African conflicts to draw in their neighbours. The Central African Republic and Small Arms unlocks the secrets of the breakdown of state capacity in a little-known but pivotal state in the heart of Africa. It also offers important new insight to options for policy-makers and concerned organizations to promote peace in complex situations.’ —Professor William Reno Associate Professor and Director of Graduate Studies, Department of Political Science, Northwestern University Photo: A mutineer during the military unrest of May 1996. -

Central African Republic Complex Emergency Fact Sheet #4 01-21

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC - COMPLEX EMERGENCY FACT SHEET #4, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2014 JANUARY 21, 2014 NUMBERS AT USAID/OFDA 1 F U N D I N G HIGHLIGHTS A GLANCE BY SECTOR IN FY 2014 Conditions in the Central African Republic (CAR) remain unstable, and insecurity continues to constrain 2.6 19% 19% humanitarian efforts across the country. million The U.S. Government (USG) provides an additional $30 million in humanitarian Estimated Number of assistance to CAR, augmenting the $15 People in CAR Requiring 12% million contributed in mid-December. Humanitarian Assistance U.N. Office for the Coordination of 26% HUMANITARIAN FUNDING Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) – December 2013 TO CAR IN FY 2014 24% USAID/OFDA $8,008,810 USAID/FFP2 $20,000,000 1.3 Health (19%) State/PRM3 $17,000,000 million Humanitarian Coordination & Information Management (26%) Estimated Number of Logistics & Relief Commodities (24%) $45,008,810 Food-Insecure People Protection (12%) TOTAL USAID AND STATE in CAR ASSISTANCE TO CAR U.N. World Food Program (WFP) – Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (19%) December 2013 KEY DEVELOPMENTS 902,000 Since early December, the situation in CAR has remained volatile, following a pattern of Total Internally Displaced rapidly alternating periods of calm and spikes in violence. The fluctuations in security Persons (IDPs) in CAR conditions continue to impede humanitarian access and aid deliveries throughout the OCHA – January 2014 country, particularly in the national capital of Bangui, as well as in northwestern CAR. Thousands of nationals from neighboring African countries have been departing CAR 478,383 since late December, increasing the need for emergency assistance within the region as Total IDPs in Bangui countries strive to cope with returning migrants. -

Iom Regional Response

IOM REGIONAL RESPONSE SITUATION REPORT │ 3 - 16 March 2015 IOM’s infrastructure cleaning activities underway, Bangui. (Photo: IOM CAR) SITUATION OVERVIEW Central African Republic (CAR): In Bangui, the situation continues to be calm albeit unpredictable. Many armed attempts of hold- ups of humanitarian actors’ vehicles and break-ins by anti-Balaka were reported in Bangui and its vicinity. Caution and vigilance CAR: IOM provided ongoing maintenance for five boreholes, have been recommended to UN and other humanitarian staffs 50 latrines and 47 emergency showers at the IDP sites locat- following criminal activities along the main roads between Bangui ed Kabo and Moyenne Sido. and several other towns. UN, NGO and private vehicles are becoming targets of regular attacks by criminal gangs with some of them posing as political or military groups. CHAD: Shelter construction continues in the Kobiteye trans- IOM, through its offices in Bangui, Kabo and Boda, has been it site near Goré with a total of 300 shelters built to date. providing assistance to IDPs, returnees and other conflict-affected populations. IOM also continues working on social cohesion through activities that include all communities, and actively participates in the UN task force in charge of preparing for the CAMEROON: IOM’s medical teams conducted consultations Parliamentary and Presidential elections which are expected to for 63 cases in Kenztou and 45 cases in Garoua Boulai. take place in CAR later in 2015. As of 3 March, there are currently 436,256 Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in CAR, including 49,113 people hosted in sites in Bangui and its environs (Source: Commission for Population host families within Kabo and Moyenne Sido. -

Saint Francis De Sales Catholic Church

Our Parish Mission Statement “To inspire all people to know, love, and serve God, by cultivating our faith Saint Francis family, embracing our cultural diversity, and serving the greater community.” Misión de nuestra Parroquia de Sales “Inspirar a todas las personas a conocer, amar y servir a Dios, Catholic Church cultivando nuestra familia de fe, Saint John the Baptist Catholic Church abrazando nuestra diversidad cultural y Diocese of Crookston sirviendo a la comunidad en general.” STAFF 601 15th Avenue North Phone (218) 233-4780 Rev. Raúl Pérez-Cobo, Pastor Moorhead, MN 56560 Web https://stfrancismhd.org [email protected] Hours M – F 8:30 a.m. – 12 noon Email [email protected] Sr. Lucy Pérez-Calixto, Guadalupe Minister 1 p.m. – 5 p.m. Facebook https://fb.me/stfrancismhd [email protected] ──────────────────────────────────────────────────── Dennis Ouderkirk, FOURTH SUNDAY OF LENT Administrative Secretary [email protected] IV Domingo de Cuaresma Devan Hirning, Coordinator of Religious Education March 14, 2021 [email protected] Luke VanOverbeke, Coordinator of Liturgy & Music [email protected] Swede Stelzer, Parish Management Coordinator [email protected] Anthony Schefter, Bulletin/Web/Sign Editor [email protected] Dean Bloch and Lucila Amezcua, Custodians Bob Seigel and Kim Bloch, Trustees Mr. Andrew Hilliker, St. Joseph’s School Principal [email protected] Phone (218) 233-0553 PASTORAL COUNCIL Brian Geffre Bob Hawk Danielle Holmes Sharon Jorschumb Shari Lee Sr. Lucy Pérez-Calixto Irma Santos “For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, Kelli Simonson Traci Steffen so that everyone who believes in him might not perish Francisco Valenzuela but might have eternal life.” (John 3:16) FINANCE COUNCIL Kim Bloch – Trustee Ann Henne Carol Nygaard Bob Seigel – Trustee THIS WEEK RITES OF PASSAGE MINISTRY SCHEDULE Check the website at Saturday 13th BAPTISM ~ We welcome those newly FRIDAY, MAR. -

Central African Republic Humanitarian Situation Report

Central African Republic Humanitarian Situation Report © UNICEFCAR/2018/Jonnaert September 2018 SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights 1.3 million # of children in need of humanitarian assistance - On 17 September, the school year was officially launched by the President in Bangui. UNICEF technically and financially supported 2.5 million the Ministry of Education (MoE) in the implementation of the # of people in need (OCHA, June 2018) national ‘Back to School’ mass communication campaign in all 8 Academic Inspections. The Education Cluster estimates that 280,000 621,035 school-age children were displaced, including 116,000 who had # of Internally displaced persons (OCHA, August 2018) dropped out of school Outside CAR - The Rapid Response Mechanism (RRM) hit a record month, with partners ensuring 10 interventions across crisis-affected areas, 572, 984 reaching 38,640 children and family members with NFI kits, and # of registered CAR refugees 59,443 with WASH services (UNHCR, August 2018) - In September, 19 violent incidents against humanitarian actors were 2018 UNICEF Appeal recorded, including UNICEF partners, leading to interruptions of assistance, just as dozens of thousands of new IDPs fleeing violence US$ 56.5 million reached Bria Sector/Cluster UNICEF Funding status* (US$) Key Programme Indicators Cluster Cumulative UNICEF Cumulative Target results (#) Target results (#) WASH: Number of affected people Funding gap : Funds provided with access to improved 900,000 633,795 600,000 82,140 $32.4M (57%) received: sources of water as per agreed $24.6M standards Education: Number of Children (boys and girls 3-17yrs) in areas 94,400 79,741 85,000 69,719 affected by crisis accessing education Required: Health: Number of children under 5 $56.5M in IDP sites and enclaves with access N/A 500,000 13,053 to essential health services and medicines.