1 Screen Acting and the New Hollywood: An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

Chris Pratt Is One of Hollywood's Most Sought

CHRIS PRATT BIOGRAPHY: Chris Pratt is one of Hollywood’s most sought- after leading men. Pratt will next appear in The Magnificent Seven opposite Denzel Washington and Ethan Hawke for director, Antoine Fuqua on September 23, 2016. Chris just wrapped production on the highly anticipated Sony sci-fi drama, Passengers opposite Jennifer Lawrence for Oscar nominated director of The Imitation Game, Morten Tyldum. The film is slated for a December 2016 release. Most recently, Chris headlined Jurassic World which is the 4th highest grossing film of all time behind Avatar, Titanic, and Star Wars: The Force Awakens. He will reprise his role of 'Owen Grady’ in the 2nd installment of Jurassic World- set for a 2018 debut. 2015 also marked the end of seventh and final season of Emmy- nominated series Parks & Recreation for which Pratt is perhaps best known for portraying the character, ‘Andy Dwyer’ opposite Amy Poehler, Nick Offerman, Aziz Ansari, and Adam Scott. 2014 was truly the year of Chris Pratt. He top lined Marvel’s Guardians of the Galaxy which was one of the top 3 grossing films of 2014 with over $770 million at the global box office. He will return to the role of ‘Star Lord’ in Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 which is scheduled for a May 2017 release. Plus, Chris lent his vocal talents to the lead character, ‘Emmett,’ in the enormously successful Warner Bros, animated feature The Lego Movie which made over $400 million worldwide. Other notable film credits include: the DreamWorks comedy Delivery Man, Spike Jonze’s critically acclaimed, Her, and the Universal comedy feature, The Five-Year Engagement. -

Wickline Casting's Film & TV Program Gwynedd Mercy Academy

Wickline Casting’s Film & TV Program at Gwynedd Mercy Academy First Trimester Thursday’s October 13, 20, November 3, 10, 17 We are thrilled to bring our very unique Film & TV course to your school. Starting in October, Wickline Casting will be “rolling camera” at your school! Your child will learn how to shine in front of the camera or learn how to make it happen “behind the scenes”. We have pulled together a special diversified course to show your child all the basics in Acting for Camera, Directing For Camera, Camera-Operating, and Scriptwriting. Everyone will learn several ways of developing commercials and film scenes from start to finish. Wickline Casting has over 10,000 credits in commercials, Academy Award winning feature films and television. We are best known for our work on “Philadelphia” with Tom Hanks and Denzel Washington, “The Long Kiss Goodnight” with Geena Davis and Samuel L. Jackson. In addition, among our television credits are numerous Cambells, Build-A-Bear, ABC Daytime Soap Operas, NBC-10, Toyota, Hasbro Toys, IKEA, AC Moore and Sesame Place. Aside from Kathy being a successful casting director, her commitment is to share filmmaking with children through after school programs and summer camps throughout PA NJ and DE. Our instructors are professional actors and directors with impressive credits. We are excited about showing young people how to bring the art of on-camera into their lives, whether it is just for fun or career aspirations. You never know…you could have the next Steven Spielberg or Jennifer Lawrence in your household! Please contact us with any questions. -

Executive Producer)

PRODUCTION BIOGRAPHIES STEVEN SODERBERGH (Executive Producer) Steven Soderbergh has produced or executive-produced a wide range of projects, most recently Gregory Jacobs' Magic Mike XXL, as well as his own series "The Knick" on Cinemax, and the current Amazon Studios series "Red Oaks." Previously, he produced or executive-produced Jacobs' films Wind Chill and Criminal; Laura Poitras' Citizenfour; Marina Zenovich's Roman Polanski: Odd Man Out, Roman Polanski: Wanted and Desired, and Who Is Bernard Tapie?; Lynne Ramsay's We Need to Talk About Kevin; the HBO documentary His Way, directed by Douglas McGrath; Lodge Kerrigan's Rebecca H. (Return to the Dogs) and Keane; Brian Koppelman and David Levien's Solitary Man; Todd Haynes' I'm Not There and Far From Heaven; Tony Gilroy's Michael Clayton; George Clooney's Good Night and Good Luck and Confessions of a Dangerous Mind; Scott Z. Burns' Pu-239; Richard Linklater's A Scanner Darkly; Rob Reiner's Rumor Has It...; Stephen Gaghan'sSyriana; John Maybury's The Jacket; Christopher Nolan's Insomnia; Godfrey Reggio's Naqoyqatsi; Anthony and Joseph Russo's Welcome to Collinwood; Gary Ross' Pleasantville; and Greg Mottola's The Daytrippers. LODGE KERRIGAN (Co-Creator, Executive Producer, Writer, Director) Co-Creators and Executive Producers Lodge Kerrigan and Amy Seimetz wrote and directed all 13 episodes of “The Girlfriend Experience.” Prior to “The Girlfriend Experience,” Kerrigan wrote and directed the features Rebecca H. (Return to the Dogs), Keane, Claire Dolan and Clean, Shaven. His directorial credits also include episodes of “The Killing” (AMC / Netflix), “The Americans” (FX), “Bates Motel” (A&E) and “Homeland” (Showtime). -

Festivals of Film

Film festivals of the Silver Bear Grand Jury Prize, Never Rarely Sometimes Always. Directed by Eliza Hittman, this sensitive abortion drama was already the recipient of a Special Back in focus Jury Prize at Sundance. Film festival giants can often narrow views of world cinema and the riches on offer, writes berlinale.de Cineworld correspondent Sean Wilson, as he digs deeper into the international scene ROTTERDAM The show was stolen at the 49th edition of IFFR with he wider perception of film SUNDANCE Isaac Chung’s upbringing in the appearance of the celebrated festivals is often dictated by Taylor Swift, Anne Hathaway, Kansas; the second, Boys State, Bong Joon-ho, who debuted T Cannes. And its surface- Willem Dafoe and Elisabeth Moss is a documentary exploring a a black and white version of his level skew toward Hollywood all rolled into the 42nd Sundance mock-government election carried masterful Parasite. “I think it may glamour, above a progressive Film Festival this January. As ever, out by a group of Texas teenagers. be vanity on my art, but when awards selection, has taken the the Robert Redford-founded event sundance.org I think of the classics, they’re all in shine of its gleaming reputation mixed and matched glamorous black and white,” Bong explained. in recent years. More and more red carpet premieres (Emerald BERLINALE “I had this idea that if I turned column inches today are afforded Fennell’s black comedy Promising The noted Jeremy Irons acted my films into black and white then to ‘smaller’ festivals, such as Young Woman won critical raves), as jury president at the 2020 they’d become classics.” Venice. -

Introduction to Screenwriting 1: the 5 Elements

Introduction to screenwriting 1: The 5 elements by Allen Palmer Session 1 Introduction www.crackingyarns.com.au 1 Can we find a movie we all love? •Avatar? •Lord of the Rings? •Star Wars? •Groundhog Day? •Raiders of the Lost Ark? •When Harry Met Sally? 2 Why do people love movies? •Entertained •Escape •Educated •Provoked •Affirmed •Transported •Inspired •Moved - laugh, cry 3 Why did Aristotle think people loved movies? •Catharsis •Emotional cleansing or purging •What delivers catharsis? •Seeing hero undertake journey that transforms 4 5 “I think that what we’re seeking is an experience of being alive ... ... so that we can actually feel the rapture being alive.” Joseph Campbell “The Power of Myth” 6 What are audiences looking for? • Expand emotional bandwidth • Reminder of higher self • Universal connection • In summary ... • Cracking yarns 7 8 Me 9 You (in 1 min or less) •Name •Day job •Done any courses? Read any books? Written any screenplays? •Have a concept? •Which film would you like to have written? 10 What’s the hardest part of writing a cracking screenplay? •Concept? •Characters? •Story? •Scenes? •Dialogue? 11 Typical script report Excellent Good Fair Poor Concept X Character X Dialogue X Structure X Emotional Engagement X 12 Story without emotional engagement isn’t story. It’s just plot. 13 Plot isn’t the end. It’s just the means. 14 Stories don’t happen in the head. They grab us by the heart. 15 What is structure? •The craft of storytelling •How we engage emotions •How we generate catharsis •How we deliver what audiences crave 16 -

Richard Linklater

8 Monday April 22 2013 | the times arts artscomedy DESPINA SPYROU; GRAEME ROBERTSON “Studioshave financedfourofmy [23]films.Idon’thave aproblemwith Find thenextbig thing Theone-nightstand Hollywood,butthe airwe breathe hereisn’tpermeatedbybusiness. My familylifeishere.” Linklateris unmarried(“Iam Go to Edinburgh anti-institutionalineveryareaofmy life”).He andTina,hispartnerof andjoin thepanel thatsparked aclassic 20years,have threemuch-cherished daughters—19-year-oldLorelei, an actress,and the8-year-old“fascinating” that decides who identicaltwinsCharlotte andAlina. “That’s abig gapbetweenchildren,”he is thestand-up ThedirectorRichard Linklater tells Tim Teeman says.“Tinasaid:‘I wantmorekidsand ifyoudon’tI’ll gohave themwith comedianof2013 thebittersweet story of abrief encounterwitha someoneelse’,” Linklaterlaughs. He quotesastatisticthat70 percentof oyouwant togo tothe strangerthatgaveusBeforeSunrise andits sequels marriedmen and72percentofmarried EdinburghFestivalFringefor women havestrayed.Isheoneofthe afortnight andstay there hosewhoracefor chanceonenight inVienna.Lehrhaupt, monogamousones?“No, of coursenot!” free?Thinkyoucouldhandle theexitasamovie’s Linklaterrevealsforthefirsttime,was heroars.“Anyonewhowantsto bewith D morethan 100hours of closingcredits rollwill thewoman with“crazy, cute,wonderful mehastoacceptthecomplexityofbeing comedyintwoweeks?Thenyouhave miss,at theendof We talked energy”hemetonenight inOctober ahuman.Itrynotto live inastraitjacket. whatittakesto beaFoster’sEdinburgh RichardLinklater’s aboutart, 1989who inspiredthefilms.“What -

The New Hollywood Films

The New Hollywood Films The following is a chronological list of those films that are generally considered to be "New Hollywood" productions. Shadows (1959) d John Cassavetes First independent American Film. Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) d. Mike Nichols Bonnie and Clyde (1967) d. Arthur Penn The Graduate (1967) d. Mike Nichols In Cold Blood (1967) d. Richard Brooks The Dirty Dozen (1967) d. Robert Aldrich Dont Look Back (1967) d. D.A. Pennebaker Point Blank (1967) d. John Boorman Coogan's Bluff (1968) – d. Don Siegel Greetings (1968) d. Brian De Palma 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) d. Stanley Kubrick Planet of the Apes (1968) d. Franklin J. Schaffner Petulia (1968) d. Richard Lester Rosemary's Baby (1968) – d. Roman Polanski The Producers (1968) d. Mel Brooks Bullitt (1968) d. Peter Yates Night of the Living Dead (1968) – d. George Romero Head (1968) d. Bob Rafelson Alice's Restaurant (1969) d. Arthur Penn Easy Rider (1969) d. Dennis Hopper Medium Cool (1969) d. Haskell Wexler Midnight Cowboy (1969) d. John Schlesinger The Rain People (1969) – d. Francis Ford Coppola Take the Money and Run (1969) d. Woody Allen The Wild Bunch (1969) d. Sam Peckinpah Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969) d. Paul Mazursky Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid (1969) d. George Roy Hill They Shoot Horses, Don't They? (1969) – d. Sydney Pollack Alex in Wonderland (1970) d. Paul Mazursky Catch-22 (1970) d. Mike Nichols MASH (1970) d. Robert Altman Love Story (1970) d. Arthur Hiller Airport (1970) d. George Seaton The Strawberry Statement (1970) d. -

Christopher Plummer

Christopher Plummer "An actor should be a mystery," Christopher Plummer Introduction ........................................................................................ 3 Biography ................................................................................................................................. 4 Christopher Plummer and Elaine Taylor ............................................................................. 18 Christopher Plummer quotes ............................................................................................... 20 Filmography ........................................................................................................................... 32 Theatre .................................................................................................................................... 72 Christopher Plummer playing Shakespeare ....................................................................... 84 Awards and Honors ............................................................................................................... 95 Christopher Plummer Introduction Christopher Plummer, CC (born December 13, 1929) is a Canadian theatre, film and television actor and writer of his memoir In "Spite of Myself" (2008) In a career that spans over five decades and includes substantial roles in film, television, and theatre, Plummer is perhaps best known for the role of Captain Georg von Trapp in The Sound of Music. His most recent film roles include the Disney–Pixar 2009 film Up as Charles Muntz, -

Genetics, Bioethics and Space Travel: GATTACA

Regulars Cyberbiochemist Genetics, Bioethics and Space Travel: GATTACA Clare Sansom (Birbeck College, London, UK) It has been said that all stories set in the future say more about the concerns of the time in which they are Downloaded from http://portlandpress.com/biochemist/article-pdf/34/6/34/3328/bio034060034.pdf by guest on 27 September 2021 written than they do about future possibilities. Long before the genome era, writers were investigating the possibility of changing the biological make-up of humans. Questions about human biology, identity and eugenics (from the Greek ‘well-born’) have been raised by writers ever since Plato; classic novels addressing these issues include H.G. Wells’s The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896) and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1931). Eugenics in fiction passed out of fashion after the Second World War, but recent developments in genetics and genomics have brought these ideas into the foreground again. The science fiction film GATTACA was released in 1997, astronaut. He studies and trains hard despite knowing that, only 2 years after the publication of the first bacterial thanks to his genetic identity, he has zero chance of success: genome sequence. The story it tells is therefore one of the “The only way you’ll see the inside of a spaceship will be first fictional explorations of these issues in the genome if you’re cleaning it”, says his father, dispassionately. It is era. For this Christmas edition of The Biochemist, your almost impossible for him to escape the genetic identity that Cyberbiochemist editor is turning film critic to confirms him as a member of the underclass, as his profile discuss it. -

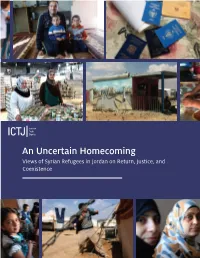

An Uncertain Homecoming Views of Syrian Refugees in Jordan on Return, Justice, and Coexistence

An Uncertain Homecoming Views of Syrian Refugees in Jordan on Return, Justice, and Coexistence INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE An Uncertain Homecoming Views of Syrian Refugees in Jordan on Return, Justice, and Coexistence RESEARCH REPORT Acknowledgments The International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) acknowledges the support of the UK Department for International Development, which funded this research and publication. ICTJ and the authors of the report also gratefully acknowledge all of those who generously gave their time to be interviewed for this report and contributed their experiences and insights. About the Authors Cilina Nasser wrote sections V through XII of this report and led the development of the Introduction and Recommendations. Nasser is a Beirut-based independent researcher and expert on human rights who also works on transitional justice issues. She has worked extensively on investigating human rights abuses and violations of international humanitarian law, primarily in Syria, but also in other countries in the Middle East and North Africa region, such as Yemen, Libya, and Saudi Arabia. She was a researcher at Amnesty International focusing on countries in crisis and conflict from 2009 to 2015 and, before that, a journalist who covered major events in Lebanon. Zeina Jallad Charpentier wrote sections III, XIII, and XIV of this report. Jallad Charpentier is a legal consultant, researcher, and lecturer in law, whose work focuses on the intersection between international law, human rights law, social mobility, access to justice and resilience of disenfranchised populations, refugees, and impact litigation. She has worked in the United States, Tunisia, Morocco, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Turkey. -

GATTACA Written and Directed by Andrew Niccol ABOUT THE

Article on Gattaca by Mark Freeman Area of Study 1 & 2 Theme: Future worlds GATTACA Written and directed by Andrew Niccol Article by Mark Freeman ABOUT THE DIRECTOR Andrew Niccol, a screenwriter and director, was born in New Zealand and moved to England at the age of 21 to direct commercials. He has written and directed Gattaca, Simone and Lord of War as well as earning an Academy Award nomination for his screenplay for The Truman Show. OVERVIEW In recent years, scientific research has unearthed a greater understanding of our genetic make-up – the lottery that determines our appearance and physical capabilities. The means by which we inherit specific traits from our parents, our genes are like a blueprint of our future, determining our predisposition for specific talents or particular illnesses. Concurrent with this understanding of genetics have come successful attempts in cloning, and, more recently, the ethical debate over stem cell research to combat a range of physical maladies. Identification and eradication of rogue genes (those that could ultimately cause malfunction at birth or later in a person’s life) is a very real possibility with the developing exploration in genetic research. In your own DNA, you already carry the genetic code which will cause your physical development in your teens, your predisposition to weight gain in your twenties, your hair loss in your thirties, early menopause in your forties, the arthritis you develop in your fifties, your death from cancer in your seventies. It’s an imposing thought to consider the map of our histories, our futures, in terms of our genetic code.