Jap Pilot Bombed US

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chetco Bar BAER Specialist Reports

Chetco Bar BAER Specialist Reports Burned Area Emergency Response Soil Resource Assessment Chetco Bar Fire OR-RSF-000326 Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest October 2017 Lizeth Ochoa – BAER Team Soil Scientist USFS, Rogue River-Siskiyou NF [email protected] Kit MacDonald – BAER Team Soil Scientist USFS, Coconino and Kaibab National Forests [email protected] 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Chetco Bar fire occurred on 191,197 acres on the Gold Beach and Wild Rivers Ranger District of the Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest, BLM lands, and other ownerships in southwestern Oregon. Approximately 170,321 acres of National Forest System (NFS) land, 6,746 acres of BLM land and 14,130 acres of private land were affected by this wildfire. Within the fire perimeter, approximately 14,012 acres burned at high soil burn severity, 64,545 acres burned at moderate soil burn severity, 76,613 acres burned at low soil burn severity, and 36,027 remain unburned. On NFS-managed lands, 10,684 acres burned at high soil burn severity, 58,784 acres burned at moderate soil burn severity, 70,201 acres burned at low soil burn severity and 30,642 acres remain unburned or burned at very low soil burn severity (Figure 1). The Chetco Bar fire burned area is characterized as steep, rugged terrain, with highly dissected slopes and narrow drainages. Dominant surficial geology is metamorphosed sedimentary and volcanic rocks, peridotite and other igneous rocks. Peridotite has been transformed into serpentine through a process known as serpentinization. This transformation is the result of hydration and metamorphic transformation of ultramafic (high iron and magnesium) rocks. -

Longley Meadows Fish Habitat Enhancement Project Heritage Resources Specialist Report

Longley Meadows Fish Habitat Enhancement Project Heritage Resources Specialist Report Prepared By: Reed McDonald Snake River Area Office Archaeologist Bureau of Reclamation June 20, 2019 Heritage Resources Introduction This section discusses the existing conditions and effects of implementation of the Longley Meadows project on cultural resources, also known as heritage resources, which are integral facets of the human environment. The term “cultural resources” encompasses a variety of resource types, including archaeological, historic, ethnographic and traditional sites or places. These sites or places are non- renewable vestiges of our Nation’s heritage, highly valued by Tribes and the public as irreplaceable, many of which are worthy of protection and preservation. Related cultural resource reports and analyses can be found in the Longley Meadows Analysis File. Affected Environment Pre-Contact History The Longley Meadows area of potential effect (APE) for cultural resources lies within the Plateau culture area, which extends from the Cascades to the Rockies, and from the Columbia River into southern Canada (Ames et al. 1998). Most of the archaeological work in the Columbia Plateau has been conducted along the Columbia and Snake Rivers. This section discusses the broad culture history in the Southern Plateau. Much variability exists in the Plateau culture area due to the mountainous terrain and various climatic zones within it. Plateau peoples adapted to these differing ecoregions largely by practicing transhumance, whereby groups followed -

Longley Meadows Fish Habitat Enhancement Project

United States Department of Agriculture Bonneville Power Administration Forest Service Department of Energy Longley Meadows Fish Habitat Enhancement Project Environmental Assessment La Grande Ranger District, Wallowa-Whitman National Forest, Union County, Oregon October 2019 For More Information Contact: Bill Gamble, District Ranger La Grande Ranger District 3502 Highway 30 La Grande, OR 97850 Phone: 541-962-8582 Fax: 541-962-8580 Email: [email protected] In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet

RECEIVED 2280 NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) Oregon WordPerfect 6.0 Format (Revised July 1998) National Register of Historic Places iC PLACES Registration Form • NATIONAL : A SERVICE This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking Y in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A"for "not applicable. For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NFS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name The La Grande Commercial Historic District other names/site number N/A 2. Location street & number Roughly bounded by the U.P Railroad tracts along Jefferson St, on __not for publication the north; Greenwood and Cove streets on the east; Washington St. on __ vicinity the south; & Fourth St. on the west. city or town La Grande state Oregon code OR county Union code 61 zip code 97850 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this ^nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

History News Issue.341 April 2019

HISTORY NEWS ISSUE.341 APRIL 2019 INSIDE THIS ISSUE President’s Report What’s On 2019 AGM Japanese Reconnaissance Flight Frances Barkman Norma Mullins Lucy Bracey Eaglehawk Mechanics Institute Heritage Report Art Captured Victoria House Around the Societies Books received History Victoria Bookshop Prisoner at Camp 13 Annual AGL Shaw Lecture in partnership with the C J La Trobe President’s Report Society: RHSV NEWS RHSV ‘Garryowen: The Voice of Early Melbourne’ by Dr Liz Rushen, Chair History Council of Victoria I am writing this from History House. I draw the attention of all members to the RHSV has long aspired to develop the notice of the Annual General Meeting Tuesday 16 April 2019, 6.30 for 7pm Drill Hall as Melbourne’s History House, that is to be held on Tuesday 21 May. RHSV Offi cers’ Mess Upstairs and in its March meeting Council agreed One important aspect of the evening will This lecture will explore how Edmund Finn’s that we should start using the title on our be consideration of a several changes to 1888 impressions of pre-1851 Melbourne letterhead, website, etc, as a small start in the RHSV Constitution. These are mainly shaped what people understood to be achieving our ambition. updates to recognise current practices relevant, important, democratic, and even As reported previously, we have been (such as the use of email addresses, and Victorian. focusing on strengthening the RHSV membership renewal via the website) Note to RHSV members: this is not a free Council, and the RHSV Foundation. It and clarifi cation of matters such as the event and bookings are available through is critical that the Foundation is able to capacity of the Council to make By-Laws. -

VIETNAMESE PRESIDENT UNHURT in ATTACK Vandenberg AIR FORCE BASE, Calif., FEB

HIGH TIDE lOW TIDE 3/1/62 3.9 AT 1156 3/1/62 2.3 AT 0444 3/2/62 3.4 AT 0103 RGLASS 3/1/62 2.1 AT 1912 VOL. 3 No. 1055 KWAJALEIN MARSHAll iSLANDS WEDNESDAY 28 fEBRUARY I 62 DISCOVERER NOo 38 SENT INTO ORBIT FROM VANDENBERG VIETNAMESE PRESIDENT UNHURT IN ATTACK VANDeNBeRG AIR FORCE BASE, CALif., FEB. 27 (UPi)-DISCOVERER No. 38 SATEL SAIGON, FEB. 27 (UPI)-THE PRESIDENTIAL PALACE WAS BOMBI' AND STRAfED BY LITE WAS HURLED INTO POLAR ORBIT TO fOUR VIETNAMESE AIR FORCE PLANES TODAY BUT PRESiDENT NGG DINH DIEM AND HIS DAY fROM THIS PACIFIC MISSILE RANGE FAMILY ESCAPED UNHURT. BASE, MARKING COMPLETION OF THREE DIEM, IN A STATEMENT OVER RADIO SAIGON SAID: YEARS IN THIS SPACE INFORMATION PRO "THANKS TO DIViNE PROTECTION i MYSELF AND MY CLOSE COLLABORATORS WERE NOT GRAM. IN DANGER. WE SUffERED ONLY MATERIAL DAMAGE." No. 38, CARRYING AN INSTRUMENT ALL AIR FORCE BASES WERE ALERTED AND ALL MEASURES Of SECURITY WERE TAKEN. PACKAGE CONTAINING UNDISCLOSED EXPERI ALL OffiCERS WERE TO fUNCTION NORMALLY AND THE POPULATION SHOULD REMAIN CALM MENTS, WAS LAUNCHED AT 11.39 A.M. AND fULFILL TrlEIR DUTIES. PST ( 9 39 A.M. HST) AND AN HOUR AND THE PRESIDENT LEFT SAIGON ON A "REGULARLY SCHEDULED TRIP" AT 0805 SAIGON A HALF LATER THE AIR fORCE RECEIVED TIME (0015 GMT). IT WAS NOT KNOWN EXACTLY WHERE HE WENT. WORD FROM TRACKING STATIONS IN HAWAI I THE PLANE'S PILOT, IDENTifiED AS LIEUTENANT PHAM PHO UOC, LANDED SAFf:L YIN AND ALASKA THAT iT HAD GONE INTO OR- THE RIVER AND WAS PROMPTLY ARRESTED, SAIGON RADIO SAID. -

164Th Infantry News: May 1999

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons 164th Infantry Regiment Publications 5-1999 164th Infantry News: May 1999 164th Infantry Association Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/infantry-documents Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation 164th Infantry Association, "164th Infantry News: May 1999" (1999). 164th Infantry Regiment Publications. 53. https://commons.und.edu/infantry-documents/53 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in 164th Infantry Regiment Publications by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ....... =·~· THE 164 TH INFANTRY NEWS Vot39·No.X May X, 1999 164th J[nfantry Memorial Monument Walter Johnson departed this vale of tears 18 December proud of this. 1998 but he left us with the beautiful 1641h Infantry Memorial It was the last project of his career. Johnson was a long Monument, Veterans Cemetery, Mandan, North Dakota. time member of the American Institute of Architects, he was Johnson served in the 1641h from 1941 -1945 and returned to very proud of the initials AIA behind his name. In designing U.S. from the Philippines he completed his professional the 1641h monument Walter refused any Architectural fees schooling as an Architect at NDSU. Walt Johnson's creative offered to him. Thanks Walter Johnson. and design skills produced the 1641h monument, he was very Before Walter T. Johnson slipped away he was working in memory of deceased 164th Infantry men. on a project in which he really believed. -

USAF Combat Airfields in Korea and Vietnam Daniel L

WINTER 2006 - Volume 53, Number 4 Forward Air Control: A Royal Australian Air Force Innovation Carl A. Post 4 USAF Combat Airfields in Korea and Vietnam Daniel L. Haulman 12 Against DNIF: Examining von Richthofen’s Fate Jonathan M. Young 20 “I Wonder at Times How We Keep Going Here:” The 1941-1942 Philippines Diary of Lt. John P. Burns, 21st Pursuit Squadron William H. Bartsch 28 Book Reviews 48 Fire in the Sky: Flying in Defense of Israel. By Amos Amir Reviewed by Stu Tobias 48 Australia’s Vietnam War. By Jeff Doyle, Jeffrey Grey, and Peter Pierce Reviewed by John L. Cirafici 48 Into the Unknown Together: The DOD, NASA, and Early Spaceflight. By Mark Erickson Reviewed by Rick W. Sturdevant 49 Commonsense on Weapons of Mass Destruction. By Thomas Graham, Jr. Reviewed by Phil Webb 49 Fire From The Sky: A Diary Over Japan. By Ron Greer and Mike Wicks Reviewed by Phil Webb 50 The Second Attack on Pearl Harbor: Operation K and Other Japanese Attempts to Bomb America in World War II. By Steve Horn. Reviewed by Kenneth P. Werrell 50 Katherine Stinson Otero: High Flyer. By Neila Skinner Petrick Reviewed by Andie and Logan Neufeld 52 Thinking Effects: Effects-Based Methodology for Joint Operations. By Edward C. Mann III, Gary Endersby, Reviewed by Ray Ortensie 52 and Thomas R. Searle Bombs over Brookings: The World War II Bombings of Curry County, Oregon and the Postwar Friendship Between Brookings and the Japanese Pilot, Nobuo Fujita. By William McCash Reviewed by Scott A. Willey 53 The Long Search for a Surgical Strike: Precision Munitions and the Revolution in Military Affairs. -

When Japan Bombed Oregon

The Day Japan Bombed Oregon <http://acmp.com/blog/the‐day‐japan‐bombed‐oregon.html> September 9, 1942 , the I‐25 class Japanese If this test run were successful, Japan had submarine was cruising in an easterly direction hopes of using their huge submarine fleet to raising its periscope occasionally as it neared attack the eastern end of the Panama Canal to the United States Coastline. slow down shipping from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Japan had attacked Pearl Harbor less than a year ago and the Captain of the attack The Japanese Navy had a large number of submarine knew that Americans were watching I‐400 submarines under construction. their coast line for ships and aircraft that might attack our country. Each capable of carrying three aircraft. Dawn was approaching; the first rays of the sun Pilot Chief Warrant Officer Nobuo Fujita and were flickering off the periscopes lens. his crewman Petty Officer Shoji Okuda were making last minute checks of their charts Their mission; attack the west coast with making sure they matched those of the incendiary bombs in hopes of starting a submarines navigator. devastating forest fire. The only plane ever to drop a bomb on the United States during WWII was this Japanese submarine based Glen. September 9, 1942: Nebraska forestry It was cold on the coast this September morning student Keith V. Johnson was on duty atop and quiet. a forest fire lookout tower between Golds Beach and Brookings Oregon . The residents of the area were still in bed or preparing to head for work. -

Seopaf Gamf B'j/ Rfcbor:O S

seopaf gamf B'J/ RfcboR:O s. ogaRa St. I 96826 ~~~~~~~~ THE JAPANESE-AMERICAN CREED Mike Masaoka I am proud that I a m an American citizen of Japanese ancestry, for my very background make me appreciate more fully the wonderful advantages of this Nation, I believe in her institutions, ideals, and traditions; I glory in her heritage; I boast of her history; I trust in her future. She has granted me liberties and opportunities such as no individual enjoys in this world today. She has given me an education befitting kings. She has entrusted me with the responsibilities of the fra nchise. She has permitted me to build a home, to earn a livelihood, to worship, think, speak, and act as I please- as a free man equal to every other man. Although some individuals may discriminate against me, I shall never become bitter or lose faith, for I know such persons are not representative of the majority of the American people. True, I shall do all in my power to discourage such practices, but I shall do it in the American way; above board, in the open, through courts of law, by education, by proving myself to be worthy of equal treatment and consideration. I am firm in my belief that American sportsmanship and attitudes of fair play will judge citizenship and patriotism on the basis of action and achievement, and not on the basis of physical characteristics. Because I believe in America, and I trust she believes in me, and because I have received innumerable benefits from her, I pledge myself to do honor to her at all times and all places; to support her constitution; to obey her laws, to respect her flag; to defend her against all enemies, foreign or domestic, to actively assume my duties and obligations as a citizen, cheer fully and without any reservations whatsoever, in the hope that I may become a better American in a great America. -

Tenth Biennial Report of the State Depart

STATE OF OREGON DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES I 069 State Office Building Portland I, Oregon BULLETIN No. 47 TENTH BIENNIAL REPORT of the State Department of Geology and Mineral Industries of the STATE OF OREGON July I, 1954, to July I, 1956 To His Excellency the Governor and the Forty-ninth Legislative Assembly ' . •. 1956 STATE GOVERNING BOARD MASON L. BINGHAM, CHAIRMAN • • • PORTLAND NIEL R. ALLEN • • • • • • • GRANTS PASS AUSTIN DUNN • • • • • • BAKER HOLLIS M. DOLE DIRECTOR TENTH BIENNIAL REPORT STATE of OREGON DEPARTMENT of GEOLOGY and MINERAl INDUSTRIES 1954-1956 CONTENTS Letter of Transmittal The Governing Board 2 The Department 3 Department Activities . 4 Services • 4 Office 4 Field . 5 Laboratory 5 Miscellaneous 7 Research • . • • 8 Oil and Gas Administration 10 Cooperative Work • • •• 12 Pub I ications and PubI ications in Progress 14 Personnel • . • • • 20 Financial Statement 21 Appropriations 21 Comparative Statements of Expenditures according to Bienniums . • • • • . • • • 22 Geology and Mineral Industries Account 24 Oregon's Mineral I ndustry . 25 Industrial Minerals • 25 Processing Plants 30 Metals •••..• 30 Electro-Process PI ants 34 Oil and Gas Exploration 34 Status of Topographic and Geologic Maps in Oregon 38 Maps Field Examinations • • . • . 6 Field Studies . • . • . 9 New and Proposed Mineral Industry Developments . • Opposite page 26 Sedimentary Basins in Oregon II II 34 Topographic Maps of Oregon . II II 38 Published Geological Maps 41 Published Geological Maps 43 MASON 1.. BINGHAM. CHAIRMAN, �OIITLAND 1038 PUI:aT STR&IIT NIEL R. ALLEN, GII:AttTS �As• AUSTIN DUNN. BAK•II GRANTS II'ASS STATE OF OREGON DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINERA L INDUSTRIES 10811 STATE OFFICE BUILDING POR TLA ND 1 To His Excellency The Governor of the State of Oregon and ta The Forty-ninth Legislative Assembly of the State of Oregon Sirs: We submit herewith the Tenth Biennial Report of the Department of Geology and Mineral Industries, covering activities of the Department for the period from July 1, 1954, to and including June 30, 1956. -

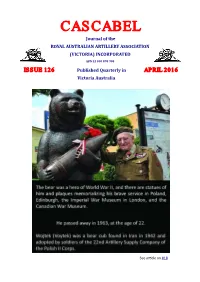

Issue126 – Apr 2016

CASCABEL Journal of the ROYAL AUSTRALIAN ARTILLERY ASSOCIATION (VICTORIA) INCORPORATED ABN 22 850 898 908 ISSUE 126 Published Quarterly in APRIL 2016 Victoria Australia See article on #18 Article Pages Assn Contacts, Conditions & Copyright 3 The President Writes 5 Letters to the Editor 6 VALE Brig Keith Rossi AM OBE RFD ED (Retd) 8 VALE Ssgt Barry Irons 10 Women in Combat 12 Lithgow business making Diggers' new rifle 13 Letters to the Editor (cont.) + The Last Fighter Pilot of WWII 14 JAPANESE RECONNAISSANCE FLIGHT OVER MELBOURNE 15 ARTICLE FROM “PACIFIC STARS & STRIPES” 22 Sep 1970 18 Wojtek (continued from page 1 20 Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal. 20 Honoured...WW2 vet who saluted Iraq heroes 22 Season’s Greetings from our troops overseas 24 Writes of passage for ‘forgotten army’ 25 Cutting-edge hot air balloon, 26 Explosive Detection Dog and Handler Sculpture Dedication 27 2016 Coral National Gunner Dinner 28 Determined to serve 29 Remembering Tobruk in 2016 31 ‘Gate Guard’ Grand Slam bomb – was actually LIVE!!!! 32 Commemorations Recognising our KIAs in Vietnam: 33 Mount Schanck Trophy Re-established 34 Parade Card/Changing your address? See cut-out proforma 35 Current Postal Addresses All mail for the Editor of Cascabel, including articles and letters submitted for publication, should be sent direct to: Alan Halbish 115 Kearney Drive, Aspendale Gardens Vic 3195 (H) 9587 1676 [email protected] 2 CASCABEL FORMER PATRONS, PRESIDENTS & HISTORY FOUNDED: JOURNAL NAME: CASCABEL - Spanish - Origin as small bell or First AGM April 1978 Campanilla (pro: Kaskebell), spherical bell, knob First Cascabel July 1983 like projection.