The Material Culture of Women's Accessories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of Brassiere in the 20Th Century

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Honors Theses Lee Honors College 12-10-2012 The Evolution of Brassiere in the 20th Century Jolene Khor Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Khor, Jolene, "The Evolution of Brassiere in the 20th Century" (2012). Honors Theses. 2342. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses/2342 This Honors Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Lee Honors College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Head: The Evolution of Brassiere in the 20th Century 1 The Evolution of Brassiere in the 20th Century Jolene Khor Western Michigan University The Evolution of Brassiere in the 20th Century 2 Abstract It is common knowledge that a brassiere, more widely known as a bra, is an important if not a vital part of a modern woman’s wardrobe today. In the 21st century, a brassiere is no more worn for function as it is for fashion. In order to understand the evolution of function to fashion of a brassiere, it is necessary to account for its historical journey from the beginning to where it is today. This thesis paper, titled The Evolution of Brassiere in the 20th Century will explore the history of brassiere in the last 100 years. While the paper will briefly discuss the pre-birth of the brassiere during Minoan times, French Revolution and early feminist movements, it will largely focus on historical accounts after the 1900s. -

Clothing Construction Registration Form

Due June 15 Due June 15 CLOTHING CONSTRUCTION REGISTRATION FORM Name___________________________ Birthdate________________ Telephone Number (___)_____________ County___________________________ Club ____________________________________________________ ---Enter all items you will bring to be judged by marking the appropriate box(es) on this sheet. Enter each class only one time.--- General Clothing STEAM Clothing 2 - Simply Sewing ❑ Clothing Portfolio ❑ Design Basics, Understand Design Principles ❑ Textile Science Scrapbook ❑ Pressing Matters ❑ Sewing for Profit ❑ Upcycled Garment ❑ Upcycled Clothing Accessory Beyond the Needle ❑ Textile Clothing Accessory ❑ Beginning Embellished Garment ❑ Top (vest acceptable) Beginning Textile Clothing Accessory Bottom (pants or shorts) ❑ ❑ ❑ Upcycled Garment ❑ Skirt ❑ Design Portfolio ❑ Lined or Unlined Jacket (non-tailored) ❑ Color Wheel ❑ Dress (not formal wear) ❑ Embellished Garment with Original Design ❑ Romper or Jumpsuit ❑ Original Designed Fabric Yardage ❑ Two-Piece Outfit ❑ Item Made from Original Designed Fabric ❑ Alter Your Pattern ❑ Textile Arts Garment or Accessory ❑ Garment Made from Sustainable or Unconventional Fibers ❑ Beginning Fashion Accessory Other Garment or Accessory ❑ Advanced Fashion Accessory ❑ Wearable Technology Garment ❑ STEAM Clothing 3 - A Stitch Further ❑ Wearable Technology Accessory ❑ Upcycled Garment STEAM Clothing 1 - Fundamentals ❑ Upcycled Clothing Accessory Textile Clothing Accessory ❑ Clothing Portfolio ❑ Sewing Kit ❑ Dress or Formal ❑ Skirted Combination ❑ Fabric -

Anniversary Meetings H S S Chicago 1924 December 27-28-29-30 1984

AHA Anniversary Meetings H S S 1884 Chicago 1924 1984 December 27-28-29-30 1984 r. I J -- The United Statei Hotel, Saratop Spring. Founding ike of the American Histoncal Anociation AMERICA JjSTORY AND LIFE HjcItl An invaluable resource for I1.RJC 11’, Sfl ‘. “J ) U the professional 1< lUCEBt5,y and I for the I student • It helps /thej beginning researcher.., by puttmq basic information at his or her fingertips, and it helps the mature scholar to he sttre he or she hasn ‘t missed anything.” Wilbur R. Jacobs Department of History University of California, Santa Barbara students tote /itj The indexing is so thorough they can tell what an article is about before they even took up the abstract Kristi Greenfield ReferencelHistory Librarian University of Washington, Seattle an incomparable way of viewing the results of publication by the experts.” Aubrey C. Land Department of History University of Georgia, Athens AMERICA: HISTORY AND LIFE is a basic resource that belongs on your library shelves. Write for a complimentary sample copy and price quotation. ‘ ABC-Clio Information Services ABC Riviera Park, Box 4397 /,\ Santa Barbara, CA 93103 CLIO SAN:301-5467 AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION Ninety-Ninth Annual Meeting A I { A HISTORY OF SCIENCE SOCIETY Sixtieth Annual Meeting December 27—30, 1984 CHICAGO Pho1tg aph qf t/u’ Umted States Hotel are can the caller turn of (a urge S. B airier, phato a1bher Saratoga Sprzng, V) 1 ARTHUR S. LINK GEORGE H. DAVIS PROFESSOR Of AMERICAN HISTORY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESIDENT OF THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION 4t)f) A Street SE, Washington, DC 20003 1984 OFfICERS President: ARTHUR S. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. ‘Medicine’, in William Morris, ed., The American Heritage Dictionary (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1976); ‘medicine n.’, in The Oxford American Dictionary of Current English, Oxford Reference Online (Oxford University Press, 1999), University of Toronto Libraries, http://www.oxfordreference.com.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/ views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t21.e19038 [accessed 22 August 2008]. 2. The term doctor was derived from the Latin docere, to teach. See Vern Bullough, ‘The Term Doctor’, Journal of the History of Medicine, 18 (1963): 284–7. 3. Dorothy Porter and Roy Porter, Patient’s Progress: Doctors and Doctoring in Eighteenth-Century England (Cambridge: Polity, 1989), p. 11. 4. I am indebted to many previous scholars who have worked on popular healers. See particularly work by scholars such as Margaret Pelling, Roy Porter, Monica Green, Andrew Weir, Doreen Nagy, Danielle Jacquart, Nancy Siraisi, Luis García Ballester, Matthew Ramsey, Colin Jones and Lawrence Brockliss. Mary Lindemann, Merry Weisner, Katharine Park, Carole Rawcliffe and Joseph Shatzmiller have brought to light the importance of both the multiplicity of medical practitioners that have existed throughout history, and the fact that most of these were not university trained. This is in no way a complete list of the authors I have consulted in prepa- ration of this book; however, their studies have been ground-breaking in terms of stressing the importance of popular healers. 5. This collection contains excellent specialized articles on different aspects of female health-care and midwifery in medieval Iberia, and Early Modern Germany, England and France. The articles are not comparative in nature. -

5 April, 2018 JOAN CADDEN CURRICULUM VITAE Addresses

5 April, 2018 JOAN CADDEN CURRICULUM VITAE Addresses: History Department University of California at Davis Davis, CA 95616 U.S.A. Phone: +1-530-752-9241 1027 Columbia Place Davis, CA 95616 U.S.A. Phone: +1-530-746-2401 E-mail: [email protected] Employment: University of California at Davis, 2008-present, Professor Emerita of History; 1996-2008 Professor of History; 1996-2008, member, Science & Technology Studies Program; 2000, 2003-04, Director, Science and Technology Studies Program. Max-Planck Institut für Wissenschaftsgeschichte, 1997-98, wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiter. Kenyon College, Gambier, Ohio, 1978-96: Professor of History, 1989-1996 University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado, 1976-78: Research Associate, Ethical and Human Values Implications of Science and Technology (NSF); History Department, Visiting Instructor, Visiting Lecturer. Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., 1971-76: Assistant Professor of History of Science; Head Tutor, History and Science Program; 1991-92: Visiting Scholar. Education: Indiana University, Bloomington: Ph.D. in History and Philosophy of Science, 1971. Dissertation: "The Medieval Philosophy and Biology of Growth: Albertus Magnus, Thomas Aquinas, Albert of Saxony and Marsilius of Inghen on Book I, Chapter v of Aristotle's De generatione et corruptione." Columbia University, New York: M.A. in History, 1967. Thesis: "De elementis: Earth, Water, Air and Fire in the 12th and 13th Centuries." Centre d'Études Supérieures de Civilisation Médiévale, Université de Poitiers, France, 1965-66: Major field, Medieval -

Belief in History Innovative Approaches to European and American Religion

Belief in History Innovative Approaches to European and American Religion Editor Thomas Kselman UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE DAME PRESS NOTRE DAME LONDON Co1 Copyright © 1991 by University of Notre Dame Press Notre Dame, Indiana 46556 Ackn< All Rights Reserved Contr Manufactured in the United States of America Introc 1. Fai JoJ 2. Bo Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hi; 3. Alt Belief in history : innovative approaches to European and American religion I editor, Thomas Kselman. Th p. em. 4. "H Includes bibliographical references. anc ISBN 0-268-00687-3 1. Europe-Religion. 2. United States-Religion. I. 19: Kselman, Thomas A. (Thomas Albert), 1948- BL689.B45 1991 90-70862 270-dc20 CIP 5. Th Pat 6. Th of Sta 7. Un JoA 8. Hi~ Arr Bodily Miracles in the High Middle Ages 69 many modern historians) have reduced the history of the body to the history of sexuality or misogyny and have taken the opportunity to gig gle pruriently or gasp with horror at the unenlightened centuries be 2 fore the modern ones. 7 Although clearly identified with the new topic, this essay is none Bodily Miracles and the Resurrection theless intended to argue that there is a different vantage point and a of the Body in the High Middle Ages very different kind of material available for writing the history of the body. Medieval stories and sermons did articulate misogyny, to be sure;8 doctors, lawyers, and theologians did discuss the use and abuse of sex. 9 Caroline Walker Bynum But for every reference in medieval treatises to the immorality of con traception or to the inappropriateness of certain sexual positions or to the female body as temptation, there are dozens of discussions both of body (especially female body) as manifestation of the divine or demonic "The body" has been a popular topic recently for historians of and of technical questions generated by the doctrine of the body's resur Western European culture, especially for what we might call the Berkeley rection. -

A Complete Bibliography of Publications in Isis, 1970–1979

A Complete Bibliography of Publications in Isis, 1970{1979 Nelson H. F. Beebe University of Utah Department of Mathematics, 110 LCB 155 S 1400 E RM 233 Salt Lake City, UT 84112-0090 USA Tel: +1 801 581 5254 FAX: +1 801 581 4148 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] (Internet) WWW URL: http://www.math.utah.edu/~beebe/ 26 February 2019 Version 0.14 Title word cross-reference ⊃ [521]. 1 [511]. 1050 [362]. 10th [521]. 11th [1186, 521]. 125th [737]. 1350 [1250]. 1485 [566]. 14th [1409]. 1524 [1554]. 1528 [1484]. 1537 [660]. 1561 [794]. 15th [245]. 1600 [983, 1526, 261]. 1617 [528]. 1632 [805]. 1643 [1058]. 1645 [1776]. 1650 [864]. 1660 [1361]. 1671 [372]. 1672 [1654]. 1674 [1654]. 1675 [88]. 1680 [889]. 1687 [1147]. 1691 [1148]. 1692 [888, 371]. 1695 [296]. 16th [1823]. 1700 [864]. 1700-talets [890]. 1704 [476]. 1708 [265]. 1713 [1415]. 1733 [756]. 1741 [1494]. 1751 [1197]. 1760 [1258]. 1774 [1558]. 1777 [1909, 572]. 1780 [314, 663]. 1792 [269]. 1794 [266]. 1796 [1195, 840]. 1799 [128]. 1799/1804 [128]. 17th [1256, 623, 1813]. 1800 [1641, 100, 1343, 1044, 1655, 248, 1331]. 1802 [127, 437]. 1803 [405, 1778]. 1804 [128]. 1807 [625]. 1814 [668]. 1815 [1777]. 1820 [1660]. 1826 [1857]. 1832 [668]. 1841 [1362]. 1844 [1913, 946]. 1848 [1708]. 185 [1327]. 1850 [1230, 1391]. 1855 [442]. 1860 [301, 1232, 1917, 1367]. 1865 [445, 1263]. 1 2 1866 [253, 71]. 1868 [1019]. 1870's [674]. 1875 [1364]. 1878 [25]. 1880 [1427, 807, 1894]. 1882 [381]. 1889 [1428]. 1893 [1588]. 1894 [1921]. 1895 [896]. -

Historic Medical Perspectives of Corseting and Two Physiologic Studies with Reenactors Colleen Ruby Gau Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1998 Historic medical perspectives of corseting and two physiologic studies with reenactors Colleen Ruby Gau Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Home Economics Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gau, Colleen Ruby, "Historic medical perspectives of corseting and two physiologic studies with reenactors " (1998). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 11922. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/11922 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UME films the t®ct directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

OPEN CLASS Fruits – Vegetables – Crops Department Superintendent – Susan Gilland

OPEN CLASS Fruits – Vegetables – Crops Department Superintendent – Susan Gilland General Rules 1. All exhibits in the Fruits, Vegetables, and Crops Department are to be entered from 7:00 a.m. until noon on Friday, July 27, 2018. 2. All grain and legume samples, except corn and soybeans, should be grown in 2018. 3. Vegetables should be brushed, wiped clean, or washed gently. 4. Where class designates plate, use an 8-10 inch paper plate or foam plate. 5. All premiums will be pro-rated on a point system and will be paid on a blue, red, and white grouping. 6. All exhibitors will be limited to one entry in each class. 7. Exhibitors are limited to residents of Monroe County and parents/guardians of active 4- H/FFA members in Monroe County. 8. Entry tags should be picked up from the Monroe County Extension Office, 219 B Avenue West, (641-932-5612) before the date of the fair. They should be filled out and attached to the exhibit before entering. 9. No responsibility will be taken for loss or damage to exhibits. 10. There will be one over all Best of Show ribbon for the entire department. 11. Entries cannot be exhibited in the “other than named” class if there is a specified class for the item. 12. Exhibitors are welcome to pick up exhibits on Sunday but must be picked up by 9:30 a.m. Monday. 13. All Fruit, Vegetable, and Crop entries will be judged according to the criteria: quality, maturity at the time of the fair, and crop season. -

Home Arts - Needlework Place / Rank Name City/State Club/Farm Name

Publicity Report - Premium Placing Western Idaho Fair Standard Page 1 August 20-29, 2021 Department - 17 Home Arts - Needlework Place / Rank Name City/State Club/Farm Name Department 17 - Home Arts - Needlework Division 1 - Fair Theme Class 1 - Fair Theme 1st Judy Lamb Boise, ID 1st Dawn Rash Boise, ID 3rd Irma Atkinson Meridian, ID Division 2 - Crochet Class 4 - Thread-Doily, under 10" 1st Andrea Baer Nampa, ID 1st Kristen Hodges Boise, ID 2nd Sandra Raeder Boise, ID 3rd Sandy E Miller Eagle, ID Firebird Class 5 - Thread-Doily, 10" - 17" 1st Kristen Hodges Boise, ID 2nd Andrea Baer Nampa, ID 3rd Sandra Raeder Boise, ID 3rd Sandy E Miller Eagle, ID Firebird Class 6 - Thread-Doily, over 17" 2nd Kristen Hodges Boise, ID 3rd Andrea Baer Nampa, ID Class 7 - Household acc.-poth./dishcloth 1st Linda Marie Hilton Boise, ID Class 8 - Household acc-place/t.runnr/dr 1st Andrea Baer Nampa, ID 2nd Judy Lamb Boise, ID 2nd Sandra Raeder Boise, ID 3rd Sandy E Miller Eagle, ID Firebird Class 9 - Household acc-not listed 1st Sandy E Miller Eagle, ID Firebird Class 10 - Thread-Tablecloth 3rd Andrea Baer Nampa, ID Class 11 - Thread-Animal, Doll or Toy 2nd Judy Lamb Boise, ID 2nd Sandy E Miller Eagle, ID Firebird 3rd Sandra Raeder Boise, ID Class 12 - Thr.Any item with crochet trim 1st Megan Kasper Melba, ID Class 14 - Thread-Booties 2nd Sandra Raeder Boise, ID Class 15 - Thread-Fashion Accesory (cont.) Printed At 8/31/2021 2:10:13 PM Publicity Report - Premium Placing Western Idaho Fair Standard Page 2 August 20-29, 2021 Department - 17 Home Arts - Needlework -

Dress Code Policy

Robison Middle School Dress Code Policy Robison Middle School encourage its students to “dress for respect.” Personal appearance should not disrupt or detract from the educational environment of the school. The school administration has the right to designate which types of dress or appearance are not acceptable. The Robison Middle School and Clark County School District (Regulation 5131) Dress Code Policy is: Pants/Skirts/Dresses/Shorts All shorts, skirts, and dresses must be a minimum length of three inches above the top of the kneecap. Remember: Clothing (short skirts and some dresses) slip up when walking. Pants/shorts may not sag nor may any pants be worn which allow underwear to show. Pants/shorts must be worn at the hip and be no more than one size larger than what the student would normally wear. Students should wear a belt to assist with this issue. Pants/shorts may not be torn or ripped three inches above the kneecap. Patches that cover such tears, or leggings worn underneath such tears, are allowed. Pajamas/lounge pants are not permitted. Leggings may be worn if they are a dark color or have an appropriate print. White leggings will not be permitted unless a top is worn over that goes to three inches above the kneecap. Shirts All clothing must be sufficient to conceal all undergarments. No skin will show between the bottom of a shirt/blouse and the top of pants or skirts at any time. Prohibited tops include, but are not limited to, tank tops that have straps that are less than three inches in width, razorback tops, crop tops, strapless tops, low-cut clothing, clothing with slits, or new design tops and outfits that provide minimum coverage. -

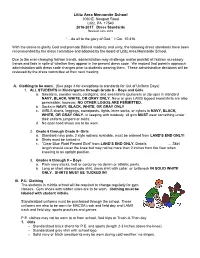

Dress Code.Pdf

Lititz Area Mennonite School 1050 E. Newport Road Lititz, PA 17543 2016-2017 Dress Standards Revised June 2016 “....do all to the glory of God.” I Cor. 10:31b With the desire to glorify God and promote Biblical modesty and unity, the following dress standards have been recommended by the dress committee and adopted by the board of Lititz Area Mennonite School. Due to the ever-changing fashion trends, administration may challenge and/or prohibit all fashion accessory trends and fads in spite of whether they appear in the present dress code. We request that parents approach administration with dress code changes prior to students wearing them. These administrative decisions will be reviewed by the dress committee at their next meeting. A. Clothing to be worn. (See page 4 for exceptions to standards for Out of Uniform Days) 1. ALL STUDENTS in Kindergarten through Grade 8 – Boys and Girls a. Sweaters, sweater vests, cardigans, and sweatshirts (pullovers or zip-ups) in standard NAVY, BLACK, WHITE, OR GRAY ONLY. Navy or gray LAMS logoed sweatshirts are also permissible; however, NO OTHER LOGOS ARE PERMITTED. b. Socks in NAVY, BLACK, WHITE, OR GRAY ONLY c. GIRLS shorts, leggings, sweatpants, tights, knee socks, or nylons in NAVY, BLACK, WHITE, OR GRAY ONLY. In keeping with modesty, all girls MUST wear something under their uniform jumpers or skirts. d. No open toed shoes are to be worn. 2. Grade 6 through Grade 8- Girls a. Standard navy polo, 3 style options available, must be ordered from LAND’S END ONLY! b. Shirts must be tucked in.