Tension and Release: Exploring the Role of Music in the Daily Life of a Men’S Local Prison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The A-Z of Brent's Black Music History

THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY BASED ON KWAKU’S ‘BRENT BLACK MUSIC HISTORY PROJECT’ 2007 (BTWSC) CONTENTS 4 # is for... 6 A is for... 10 B is for... 14 C is for... 22 D is for... 29 E is for... 31 F is for... 34 G is for... 37 H is for... 39 I is for... 41 J is for... 45 K is for... 48 L is for... 53 M is for... 59 N is for... 61 O is for... 64 P is for... 68 R is for... 72 S is for... 78 T is for... 83 U is for... 85 V is for... 87 W is for... 89 Z is for... BRENT2020.CO.UK 2 THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY This A-Z is largely a republishing of Kwaku’s research for the ‘Brent Black Music History Project’ published by BTWSC in 2007. Kwaku’s work is a testament to Brent’s contribution to the evolution of British black music and the commercial infrastructure to support it. His research contained separate sections on labels, shops, artists, radio stations and sound systems. In this version we have amalgamated these into a single ‘encyclopedia’ and added entries that cover the period between 2007-2020. The process of gathering Brent’s musical heritage is an ongoing task - there are many incomplete entries and gaps. If you would like to add to, or alter, an entry please send an email to [email protected] 3 4 4 HERO An influential group made up of Dego and Mark Mac, who act as the creative force; Gus Lawrence and Ian Bardouille take care of business. -

Tranquillity in a World of Chaos and Uncertainty

No 118 October/November 2020 Official Newsletter of SeniorNet Mac Inc. Christchurch Telephone 03 365 1979 http://seniormac.org.nz Tranquillity in a world of chaos and uncertainty.... Helping Seniors with Apple Technology Page 1 http://seniormac.org.nz From the President —Barbara Blowes SeniorNet Mac Inc. PO Box 475 Christchurch 8140 to you all, 41 Essex Street, Christchurch Web: http://seniormac.org.nz/ can’t believe how fast this year has gone. What with Covid and shifting a lot has happened to me I this year. I must admit I did enjoy having to stay Morning Sessions home during Covid; didn’t really miss going out didn't use much Monday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday petrol either so that was a saving. 10.00 am to 12 noon I managed to get a lot done and Honey loved all the extra walks we took her on. op in and have a cuppa in the learning Our shift to the new room minus stairs has proved to be a great centre. You can get answers to computer success and we are getting more members coming in on our P problems, ask questions and get advice. open mornings with their problems its great that we can help them. If you need to bring in your computer please ring: The latest update on the Watch has a neat feature; it times you when you wash your hands and a new screen shows with 03 365 1979 bubbles on it and when you have washed your hands for 20 seconds it tells you well done! I wonder what the next update and leave a message will have in it, the mind boggles but it's very clever. -

Creativity, Capital and Entrepreneurship: the Contemporary Experience of Competition in UK Urban Music

Creativity, Capital and Entrepreneurship: The Contemporary Experience of Competition in UK Urban Music George William Henry Musgrave School of Politics, Philosophy, Language & Communication Studies, and the ESRC Centre for Competition Policy (CCP), University of East Anglia Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2014 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution 1 Abstract This thesis explores how a competitive marketplace is experienced by creative labour in the context of UK urban music by employing an experimental ethnographic research approach. Between 2010-2013, observations, interviews and textual analysis were conducted with two case-study ‘MCs’, alongside reflexive autoethnographic analysis of the author’s own career as an unsigned artist. The findings contribute to the study of competitiveness by highlighting how it is understood from the perspective of producers, as well as to a wider body of qualitative academic literature exploring the ways in which creative labour operates in advanced markets. It is proposed that in an increasingly competitive context, cultural intermediaries assume a crucial role in the lives of artists for their ability to act as both a distributor and a distinguisher, thereby addressing the work of cultural sociologists and creative labour scholars that debates the role of intermediaries in cultural markets. The methods of artistic collaboration which creative labour employ to capture the attention of these intermediaries, demonstrates that competitiveness can engender collaboration. -

Rapping Postcoloniality: Akala's “The Thieves Banquet” and Neocolonial Critique

Williams, J. A. (2017). Rapping Postcoloniality: Akala's 'The Thieves Banquet' and Neocolonial Critique. Popular Music and Society, 40(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2016.1230457 Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record License (if available): CC BY-NC-ND Link to published version (if available): 10.1080/03007766.2016.1230457 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the final published version of the article (version of record). It first appeared online via Taylor & Francis at http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03007766.2016.1230457. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Popular Music and Society ISSN: 0300-7766 (Print) 1740-1712 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rpms20 Rapping Postcoloniality: Akala’s “The Thieves Banquet” and Neocolonial Critique Justin A. Williams To cite this article: Justin A. Williams (2016): Rapping Postcoloniality: Akala’s “The Thieves Banquet” and Neocolonial Critique, Popular Music and Society, DOI: 10.1080/03007766.2016.1230457 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2016.1230457 © 2016 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 29 Sep 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 34 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rpms20 Download by: [University of Bristol] Date: 14 October 2016, At: 02:13 POPULAR MUSIC AND SOCIETY, 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2016.1230457 OPEN ACCESS Rapping Postcoloniality: Akala’s “The Thieves Banquet” and Neocolonial Critique Justin A. -

Paper Tiger Steven Spielberg: Why My Film About the Power of the Press Is So Timely

January 7, 2018 THEATRE BOOKS HOT TICKETS INTERVIEW: THE STARS FRANCE’S NEW FROM PINTER TO PICASSO: OF MARY STUART LITERARY SENSATION WE PICK THE MUST-SEES OF 2018 PAPER TIGER STEVEN SPIELBERG: WHY MY FILM ABOUT THE POWER OF THE PRESS IS SO TIMELY CONTENTS 07.01.2018 ARTS ‘In Frankenstein, Mary Shelley 4 invented two kinds Cover story of being — an Steven Spielberg’s new film is about the press-led intelligent robot revolt against the Nixon administration. Yes, he tells and a scientist Bryan Appleyard, he is well who plays God’ aware of the modern parallels Books, page 30 6 Pop ALAMY Which of today’s hits will be tomorrow’s classics? Dan Cairns offers a guide BOOKS 34 The Sunday Times 14 30 Bestsellers Film Lead review Ridley Scott’s movie about the John Carey hails an DIGITAL EXTRAS Getty kidnapping is richly outstanding look at the rewarding, says Tom Shone creation of Frankenstein NICK DELANEY Bulletins 16 32 For the arts week ahead, and Television Fiction recent highlights, sign up for James Norton as a Russian A Freddie Mercury 20 Leila Slimani’s thriller has our Culture Bulletin. For a Jew? Louis Wise is still to be biopic, above, is just Critical list turned her into a French weekly digest of literary news, convinced by McMafia’s hero Our pick of the arts this week celebrity courted by reviews and opinion, there’s one of the year’s President Macron the Books Bulletin. Both can hot prospects. be found at thesundaytimes. 18 24 co.uk/bulletins Theatre We choose the On record 36 The two leads of Mary Stuart The latest essential releases -

Tiktok's Knack for Connecting Fans with Songs & Brands

Bulletin YOUR DAILY ENTERTAINMENT NEWS UPDATE JULY 21, 2021 Page 1 of 26 INSIDE TikTok’s Knack for Connecting • England’s Venues Fans With Songs & Are Open Again, But New Vaccine Brands Examined in New Study Passport Plans Stir Discontent BY TATIANA CIRISANO • Warner Music Gets Upgrade From TikTok’s influence on popular music is by now unde- songs with TikTok. S&P on Strength of niable, as challenges and trends on the video-sharing The study also sheds some light on best practices Streaming app routinely propel songs up the music charts and for brands looking to connect with TikTok users • Taylor Swift Pulls turn emerging artists into stars. But song uses on through music. When brands feature songs that are ‘Fearless (Taylor’s TikTok don’t automatically translate to streams, and popular on TikTok, 68% of users say they remember Version)’ From artists and executives have had little data to under- the brand better; 58% say they feel a stronger connec- Grammy & CMA stand how songs go from being popular on TikTok to tion to the brand; 58% say they’re more likely to talk Awards Contention: becoming a hit beyond it. about the brand or share the ad; and 62% say they’re Exclusive A new study by TikTok and MRC Data released curious to learn about the brand. • Warner Chappell today (July 21) provides some answers. In all, the study provides data to confirm things the Production Music According to the results of the study, which was music industry anecdotally already knows. But this Brand Refresh: New Logo & Exec Hires conducted on U.S. -

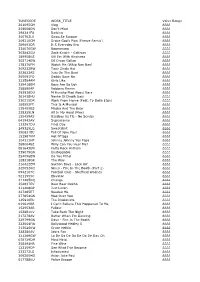

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 261095CM

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 261095CM Vlog ££££ 259008DN Don't Mind ££££ 298241FU Barking ££££ 300703LV Swag Se Swagat ££££ 309210CM Drake God's Plan (Freeze Remix) ££££ 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 234070GW Boomerang ££££ 302842GU Zack Knight - Galtiyan ££££ 189958KS Kill Em With Kindness ££££ 302714EW Dil Diyan Gallan ££££ 178176FM Watch Me (Whip Nae Nae) ££££ 309232BW Tiger Zinda Hai ££££ 253823AS Juju On The Beat ££££ 265091FQ Daddy Says No ££££ 232584AM Girls Like ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 258890AP Robbery Remix ££££ 292938DU M Huncho Mad About Bars ££££ 261438HU Nashe Si Chadh Gayi ££££ 230215DR Work From Home (Feat. Ty Dolla $Ign) ££££ 188552FT This Is A Musical ££££ 135455BS Masha And The Bear ££££ 238329LN All In My Head (Flex) ££££ 155459AS Bassboy Vs Tlc - No Scrubs ££££ 041942AV Supernanny ££££ 133267DU Final Day ££££ 249325LQ Sweatshirt ££££ 290631EU Fall Of Jake Paul ££££ 153987KM Hot N*Gga ££££ 304111HP Johnny Johnny Yes Papa ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 081643EN Party Rock Anthem ££££ 239079GN Unstoppable ££££ 254096EW Do You Mind ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 216422EM Section Boyz - Lock Arf ££££ 325052KQ Nines - Fire In The Booth (Part 2) ££££ 0942107C Football Club - Sheffield Wednes ££££ 5211555C Elevator ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 254637EV Baar Baar Dekho ££££ 311408GP Just Listen ££££ 227485ET Needed Me ££££ 277854GN Mad Over You ££££ 125910EU The Illusionists ££££ 019619BR I Can't Believe This Happened To Me ££££ 152953AR Fallout ££££ 153881KV Take Back The Night ££££ 217278AV Better When -

George Musgrave: Collaborating To

Collaborating to compete 41 Collaborating to compete: the role of cultural intermediaries in hypercompetition George Musgrave1 Abstract This article explores the role that cultural intermediaries, defined primarily as radio DJs and journalists, play in the lives of three unsigned UK urban music artists. Using semi-structured interviews, textual analysis of social media usage, and observation notes, as well as auto-ethnographic examination of the author's own career as a musician over a four-year period between 2010-13, it is suggested that intermediar- ies are of crucial importance in the lives of artists largely as distinguishers in an en- vironment of ferocious competition, which anonymises via abundance. Their role is therefore deeply symbolic, providing credible eminence. By interpreting these find- ings through a Bourdieusian lens, it is suggested that these collaborative processes of intermediary engagement, which allow musicians to acquire large reserves of in- stitutionalised cultural capital, problematise notions of success by masking the pro- found difficulties they have in converting this prestige into material rewards. There is therefore, for these musicians, a worrying ambiguity relating to how others un- derstand and value what they do, and a tension between this perception and their material reality. Keywords: popular music, cultural intermediaries, auto-ethnography, creative in- dustries, competition, Bourdieu 1 Introduction Competition is the economist's and policy maker's panacea; the bench- mark towards which markets must confidently march in order to maxim- ise consumer welfare. However, what does this mean for producers ex- periencing this competition? This paper seeks to invert the methodolog- ical gaze when looking at the impact of competition, away from the benefits for the marketplace and the consumer towards the producer, 1 George Musgrave is a senior lecturer at the University of Westminster, and a lecturer at Gold- smiths (University of London) in the Institute for Creative and Cultural Entrepreneurship. -

Volume 6, No 2, October 2017

International Journal of Music Business Research Volume 6, Number 2, October 2017 Editors: Peter Tschmuck University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna, Austria Dennis Collopy University of Hertfordshire, UK Daniel Nordgård (book review editor) University of Agder, Norway Carsten Winter University of Music, Drama and Media Hanover, Germany AIMS AND SCOPE The International Journal of Music Business Research (IJMBR) as a double-blind reviewed academic journal provides a new platform to present articles of merit and to shed light on the current state of the art of music business research. Music business research in- volves a scientific approach to the intersection of economic, artistic (especially musical), cultural, social, legal, technological developments and aims for a better understanding of the creation/production, dissemination/distribution and reception/consumption of the cultural good of music. Thus, the IJMBR targets all academics, from students to profes- sors, from around the world and from all disciplines with an interest in research on the music economy. EDITORIAL BOARD Dagmar Abfalter, University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna, Austria David Bahanovich, Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance London, UK Marc Bourreau, Université Telecom ParisTech, France Ryan Daniel, James Cook University Townsville, Australia Beate Flath, University of Paderborn, Germany Simon Frith, University of Edinburgh, Scotland, UK Victor Ginsburgh, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium Philip Graham, University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia Christian Handke, Erasmus University Rotterdam, The Netherlands Susanne Janssen, Erasmus University Rotterdam, The Netherlands Martin Kretschmer, University of Glasgow, UK Frank Linde, Cologne University of Applied Sciences, Germany Martin Lücke, Macromedia University for Media and Communication, Campus Berlin, Germany Jordi McKenzie, Macquarie University Sydney, Australia Juan D. -

2020'S BEST MUSIC MARKETING CAMPAIGNS

DECEMBER 09 2020 sandbox ISSUE 266 | Music marketing for the digital era 2020’s BEST MUSIC MARKETING CAMPAIGNS SANDBOX CAMPAIGNS OF THE YEAR 2020 2020’s BEST MUSIC MARKETING CAMPAIGNS elcome to Sandbox’s shortlist we had a record number of entries, from labels of the best, most original, and of all sizes from around the world. W most impactful music marketing campaigns of 2020. It’s a celebration of We’re very grateful for everyone who submitted remarkably innovative and creative work across campaigns for consideration – and we hope that a vast array of genres, with many notable in these campaigns you find a wealth of brilliant achievements notched up along the way. As ideas, new technologies, and daring creativity to ever, these successes are down to collaboration inspire your own work in the future. and teamwork, and we’re celebrating the people and companies that worked hard to make it all As always, campaigns are listed in alphabetical happen, too. order, but there are spot prizes throughout for the campaigns that we felt achieved something This was, of course, an exceptional and difficult special in an outstanding year. year for everyone as the global pandemic hit. Here’s the best of 2020. :) The vast majority of campaigns included here Eamonn Forde, mention how their plans were badly affected, Editor ideas were scrapped and new strategies had to be developed on the fly. EDIT methodology & notes • Labels could submit multiple campaigns. It is a testament to the indomitable spirit of the • Campaigns were selected on the basis marketing community that campaigns were able of originality, creativity, and impact. -

Fire in the Booth Soundboard

Fire in the booth soundboard Continue Charlie Slot Rap Show Editors Notes Fire in the Booth turned out to be an online phenomenon. The Charlie Sloth series showcases some of the best hip hop MCs with pressure on, and they bring their own-games every time. There's no hiding out there, says Charlie. It's just an artist, a microphone, and my sound effects. Discover some of Charlie's favorite hip hop videos, classic freestyles, and Charlie's fresh booth invites. Booth Fire, Pt.1 Pounds - Charlie Slot Fire in Booth, Pt. 3 Headie One - Charlie Slot Fire in Booth, Pt.1 Jelani Blackman - Charlie Slot Fire in Booth, Pt.4 Youngs Teflon - Charlie Slot Fire in Booth, Pt.1 Jordan and Charlie Slot Fire in Booth Nine, Pt.1 Pop Smoke - Charlie Slot Fire in Booth, Pt.4 Giggs - Charlie's Slot Baby , Pt.1 Jack Harlow and Charlie Slot Kevin Gates Fire in Booth Kevin Gates, Pt.1 SD Mooney and Charlie Slot Fire in the Stand, Pt. 1 Ink and Charlie Slot Fire in the Stand, Pt.1 Nadia Rose and Charlie Slot Fire in the Stand, Pt.1 Hack Baker and Charlie Slot Fire in the Stand, Pt.1 Digga D and Charlie Slot Fire in the Booth, Pt.1 Digga D and Charlie Slot , Pt.1 SAINt JHN and Charlie Slot Fire in the Stand, Pt.1 Unknown P - Charlie Slot Fire in the Stand, Pt.2 Northsidebenge and Charlie Slot Fire in Booth, Pt.1 JAY1 - Charlie Slot Fire in Booth, Pt. 1 DigDat and Charlie Slot Fire in Booth, Pt.1 M24, Pt.1 Slim and Charlie Slot Fire in Booth, Pt.1 K Dot - Charlie's Slot In Booth, Pt.1 Tunde - Charlie's Slot , Pt.1 OFB - Charlie Slot Fire in Booth, Pt.1 Fabolous - Charlie -

Wolverhampton & Black Country Cover

Shropshire Cover July 2017 .qxp_Shropshire Cover 26/06/2017 20:36 Page 1 TERRYTERRY ALDERTONALDERTON PLAYSPLAYS Your FREE essential entertainment guide for the Midlands SSHREWSBURYHREWSBURY COMEDYCOMEDY FESTIVALFESTIVAL ISSUEISSUE 379379 JULYJULY 20172017 SHROPSHIRE WHAT’S ON JULY 2017 ON JULY WHAT’S SHROPSHIRE Shropshire ’ WhatFILM I COMEDY I THEATRE I GIGS I VISUAL ARTS I EVENTSs I FOOD On shropshirewhatson.co.ukpshirewhatson.co.uk PART OF WHAT’S ON MEDIA GROUP GROUP MEDIA ON WHAT’S OF PART inside: Yourthe 16-pagelist week by week listings guide MISS SAIGON the heat is on as smash-hit musical lands in the Midlands TWITTER: @WHATSONSHROPS TWITTER: talksTOM Faith, ROBINSON Folk & Anarchy interview inside... FACEBOOK: @WHATSONSHROPSHIRE scienceSTEAMPUNK... fantasy festival makes its Blists Hill debut SHROPSHIREWHATSON.CO.UK (IFC) Shrops.qxp_Layout 1 26/06/2017 18:13 Page 1 Contents July Wolves_Shrops_Staffs.qxp_Layout 1 26/06/2017 12:53 Page 2 July 2017 Contents Barbarella’s Bang Bang - play Fuse Festival at Beacon Park more line-up info on page 19 Tom Robinson Miss Saigon Summer Fun the list talks Faith, Folk & Anarchy smash-hit musical lands in Places to visit and things to do Your 16-page ahead of folk festival gig the Midlands during the school holidays... week-by-week listings guide interview page 8 page 28 page 40 page 51 inside: 4. First Word 11. Food 15. Music 22. Comedy 26. Theatre 32. Film 36. Visual Arts 47. Events @whatsonwolves @whatsonstaffs @whatsonshrops Wolverhampton What’s On Magazine Staffordshire What’s On Magazine