Exhibition Hall the Noisy Return of Exhibition Hall [email protected] Yes, We’Re Back

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Runaway Pdf Free Download

RUNAWAY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Alice Munro | 368 pages | 03 May 2017 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099472254 | English | London, United Kingdom Runaway PDF Book Universal Conquest Wiki. Health Care for Women International. One of the most dramatic examples is the African long-tailed widowbird Euplectes progne ; the male possesses an extraordinarily long tail. Although a fight broke out, the X-Men accepted Molly's decision to remain with her friends, but also left the invitation open. Geoffrey Wilder 33 episodes, Our TV show goes beyond anything you have seen previously. First appearance. Entry 1 of 3 1 : one that runs away from danger, duty, or restraint : fugitive 2 : the act of running away out of control also : something such as a horse that is running out of control 3 : a one-sided or overwhelming victory runaway. How many sets of legs does a shrimp have? It is estimated that each year there are between 1. Send us feedback. In hopes to find a sense of purpose, Karolina started dabbling in super-heroics, [87] and was quickly joined by Nico. Metacritic Reviews. The Runaways outside the Malibu House. Added to Watchlist. Edit Did You Know? Sound Mix: Dolby Stereo. Runtime: 99 min. Bobby Ramsay Chris Mulkey We will share Japanese culture and travel, in a way that is exciting, entertaining and has never been done before! See also: Young night drifters and youth in Hong Kong. Company Credits. Miss Shields Carol Teesdale Episode 3 The Ultimate Detour. Hood in ," 24 Nov. Runaways have an elevated risk of destructive behavior. Alex Wilder 33 episodes, Yes No Report this. -

Rainbow Rowell • Kris Anka • Matthew Wilson

RAINBOW ROWELL • KRIS ANKA • MATTHEW WILSON MATTHEW • ANKA KRIS • ROWELL RAINBOW 0 1 2 1 1 T+ 12 US # MARVEL.COM RATED RATED $3.99 7 5 9 6 0 6 0 8 7 3 0 3 When they were younger, Nico Minoru, Chase Stein, Gertrude Yorkes, Karolina Dean, Molly Hayes and Alex Wilder became friends through circumstance: hanging out once a year while their parents had what they claimed was a dinner party. After discovering their parents were actually the super villain team known as the Pride, the kids ran. The Runaways learned to use powers and resources inherited from their parents, and returned to defeat them. The experience made them a family, but that wasn’t enough to keep them safe. When Chase used Gert’s parents’ time machine to rescue her from her death years ago, the Runaways revival began. Gert’s return gave Nico and Chase direction--a change for the better. In fact, despite anxiety around her magic and some regrets, Nico is coming into her own. Molly and Karolina were forced through their own adjustments--Molly left her grandma and Karolina’s girlfriend left. But Gert and Victor have been stuck. Maybe her recent makeover was a sign Gert’s learning who she is in the present? Victor, on the other hand, is trapped by the trauma of the mission that left him as just a head, and his refusal to talk about it. WRITER ARTIST COLOR ARTIST LETTERER RAINBOW ROWELL KRIS ANKA MATTHEW WILSON VC’S JOE CARAMAGNA COVER ARTIST GRAPHIC DESIGNER ASSISTANT EDITOR EDITOR KRIS ANKA CARLOS LAO KATHLEEN WISNESKI NICK LOWE EDITOR IN CHIEF CHIEF CREATIVE OFFICER PRESIDENT EXECUTIVE PRODUCER C.B. -

Friday, October 29Th

fridayprogramming fridayprogramming FRIDAY, OCTOBER 29TH 2 p.m.-2:45 p.m. Jackendoff as he talks with comic kingpin Marv WEBCOMICS: LIGHTING ROUND! Wolfman (Teen Titans), veteran comic writer WRITERS WORKSHOP PRESENTED by Seaside Lobby and editor Barbara Randall Kesel (Watchman, ASPEN Comics Thinking of starting a webcomic, or just curious Hellboy), comic writer Jimmy Palmiotti (Jonah Room 301 as to how the world of webcomics differs Hex), Tom Pinchuk (Hybrid Bastards) and Mickey Join comic book writers J.T. Krul, Scott Lobdell, from print counter-parts? Join these three Neilson (World of Warcraft). David Schwartz, David Wohl, Frank Mastromauro, webcomics pros [Harvey-nominated Dave Kellett and Vince Hernandez as they discuss the ins and (SheldonComics.com /DriveComic.com), Eisner- HOW TO SURVIVE AS AN ARTIST outs of writing stories for comics. Also, learn tips nominated David Malki (Wondermark.com) and WITH Scott Koblish of the trade firsthand from these experienced Bill Barnes (Unshelved.com / NotInventedHere. Room 301 writers as they detail the pitfalls and challenges of com)] as they take you through a 25-minute A panel focusing on the lifelong practical questions breaking into the industry. Also, they will answer guided tour of how to make webcomics work an artist faces. Scott Koblish gives you tips on questions directly in this special intimate workshop as a hobby, part-time job, or full-time career. how to navigate a career that can be fraught with that aspiring writers will not want to miss. Then the action really heats up: 20 minutes of unusual stress. With particular attention paid to fast-paced Q&A, designed to transmit as much thinking about finances in a realistic way, stressing 5 p.m.-7 p.m. -

Rowell • Genolet • Henrichon • Wilson

RATED $3.99 0 2 3 1 1 # 23 US T+ 7 5 9 6 0 6 0 8 7 3 0 3 BONUS DIGITAL EDITION – DETAILS INSIDE! ROWELL • GENOLET • HENRICHON • WILSON When they were younger, Nico Minoru, Chase Stein, Gertrude Yorkes, Karolina Dean, Molly Hayes and Alex Wilder became friends through circumstance: hanging out once a year while their parents had what they claimed was a dinner party. After discovering their parents were actually the super villain team known as the Pride, the kids ran. The Runaways learned to use powers and resources inherited from their parents and returned to defeat them. The experience made them a family, but that wasn’t enough to keep them safe. After months of Victor resisting Chase’s help to build him a new android body, Victor regrew one. The first thing he did was kiss Gert, and then Chase walked in. But the Runaways’ friend Doombot still needed repairs, so Victor tried to work through the tension and Chase tried to ignore it. Chase had managed to reboot Doombot, but only by unwittingly removing the tiny black hole placed in his chest as a deterrent from his destructive programming. Doombot awoke, and would have vanquished every Runaway if Victor hadn’t used some newly grown wiring to connect to his friend and attempt internal repairs. WRITER ARTIST COLOR ARTIST DOOM DIALOGUE ARTIST RAINBOW ROWELL ANDRÉS GENOLET MATTHEW WILSON NIKO HENRICHON LETTERER COVER ARTIST VC’S JOE CARAMAGNA KRIS ANKA GRAPHIC DESIGNER ASSISTANT EDITOR EDITOR CARLOS LAO KATHLEEN WISNESKI NICK LOWE EDITOR IN CHIEF CHIEF CREATIVE OFFICER PRESIDENT EXECUTIVE PRODUCER C.B. -

Playing Superhero": Agency and the Role of the Teenaged Superhero

Longwood University Digital Commons @ Longwood University Theses, Dissertations & Honors Papers Spring 4-25-2012 "Playing Superhero": Agency and the Role of the Teenaged Superhero Jessica R. Saunders Longwood University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.longwood.edu/etd Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, Fiction Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Saunders, Jessica R., ""Playing Superhero": Agency and the Role of the Teenaged Superhero" (2012). Theses, Dissertations & Honors Papers. 503. https://digitalcommons.longwood.edu/etd/503 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Longwood University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations & Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Longwood University. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. "Playing Superhero": Agency and the Role of the Teenaged Superhero by Jessica R. Saunders A thesis submitted in partial fulfillmentof the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in English Longwood University Department of English and Modem Languages Chris W. McGee, Ph.D. Thesis Director Jent er M. Miskec, Ph.D. First Reader -l.:...L-'--h,�'l-.'l-�-Htt._\14A[u-l.-<(1--- Rh011da L. Brock- 'ervais, Ph.D. Second Reader Date Table of Contents Chapter One................. ......................................................................... 1 Chapter -

SEPTEMBER ONLY! 17 & 18, 2016 Long Beach Convention Center SEE NATHAN FILLION at the PANEL!

LONG BEACH COMIC CON LOGO 2014 SAT SEPTEMBER ONLY! 17 & 18, 2016 Long Beach Convention Center SEE NATHAN FILLION AT THE PANEL! MEET LEGENDARY CREATORS: TROY BAKER BRETT BOOTH KEVIN CONROY PETER DAVID COLLEEN DORAN STEVE EPTING JOELLE JONES GREG LAND JIMMY PALMIOTTI NICK SPENCER JEWEL STAITE 150+ Guests • Space Expo Artist Alley • Animation Island SUMMER Celebrity Photo Ops • Cosplay Corner GLAU SEAN 100+ Panels and more! MAHER ADAM BALDWIN WELCOME LETTER hank you for joining us at the 8th annual Long Beach Comic Con! For those of you who have attended the show in the past, MARTHA & THE TEAM you’ll notice LOTS of awesome changes. Let’s see - an even Martha Donato T Executive Director bigger exhibit hall filled with exhibitors ranging from comic book publishers, comic and toy dealers, ENORMOUS artist alley, cosplay christine alger Consultant corner, kids area, gaming area, laser tag, guest signing area and more. jereMy atkins We’re very proud of the guest list, which blends together some Public Relations Director of the hottest names in industries such as animation, video games, gabe FieraMosco comics, television and movies. We’re grateful for their support and Marketing Manager hope you spend a few minutes with each and every one of them over DaviD hyDe Publicity Guru the weekend. We’ve been asked about guests who appear on the list kris longo but who don’t have a “home base” on the exhibit floor - there are times Vice President, Sales when a guest can only participate in a signing or a panel, so we can’t CARLY Marsh assign them a table. -

Characters – Reference Guide

Player’s Guides 01 Player’s Guide to Playing HeroClix 02 Player’s Guide to Powers and Abilities 03 Player’s Guide to Characters: Errata and Clarifications 04 Player’s Guide to Characters: Reference 05 Player’s Guide to Team Abilities 06 Player’s Guide to Maps 07 Player’s Guide to Tactics I: Objects, Resources, and Hordes 08 Player’s Guide to Tactics II: Feats and Battlefield Conditions Any game elements indicated with the † symbol may only be used with the Golden Age format. Any game elements indicated with the ‡ symbol may only be used with the Star Trek: Tactics game. Items labeled with a are available exclusively through Print-and-Play. Any page references refer to the HeroClix 2013 Core Rulebook. All Player’s Guides can be found at http://www.heroclix.com/downloads/rules Table of Contents Legion of Super Heroes† .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Avengers† ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Justice League† ................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Mutations and Monsters† ................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Marvel Checklist

Marvel Checklist Updated 6/12/19 01 Thor 23 IM3 Iron Man 02 Loki 24 IM3 War Machine 03 Spider-man 25 IM3 Iron Patriot 03 B&W Spider-man (Fugitive) 25 Metallic IM3 Iron Patriot (HT) 03 Metallic Spider-man (SDCC ’11) 26 IM3 Deep Space Suit 03 Red/Black Spider-man (HT) 27 Phoenix (ECCC 13) 04 Iron Man 28 Logan 04 Blue Stealth Iron Man (R.I.CC 14) 29 Unmasked Deadpool (PX) 05 Wolverine 29 Unmasked XForce Deadpool (PX) 05 B&W Wolverine (Fugitive) 30 White Phoenix (Conquest Comics) 05 Classic Brown Wolverine (Zapp) 30 GITD White Phoenix (Conquest Comics) 05 XForce Wolverine (HT) 31 Red Hulk 06 Captain America 31 Metallic Red Hulk (SDCC 13) 06 B&W Captain America (Gemini) 32 Tony Stark (SDCC 13) 06 Metallic Captain America (SDCC ’11) 33 James Rhodes (SDCC 13) 06 Unmasked Captain America (Comikaze) 34 Peter Parker (Comikaze) 06 Metallic Unmasked Capt. America (PC) 35 Dark World Thor 07 Red Skull 35 B&W Dark World Thor (Gemini) 08 The Hulk 36 Dark World Loki 09 The Thing (Blue Eyes) 36 B&W Dark World Loki (Fugitive) 09 The Thing (Black Eyes) 36 Helmeted Loki 09 B&W Thing (Gemini) 36 B&W Helmeted Loki (HT) 09 Metallic The Thing (SDCC 11) 36 Frost Giant Loki (Fugitive/SDCC 14) 10 Captain America <Avengers> 36 GITD Frost Giant Loki (FT/SDCC 14) 11 Iron Man <Avengers> 37 Dark Elf 12 Thor <Avengers> 38 Helmeted Thor (HT) 13 The Hulk <Avengers> 39 Compound Hulk (Toy Anxiety) 14 Nick Fury <Avengers> 39 Metallic Compound Hulk (Toy Anxiety) 15 Amazing Spider-man 40 Unmasked Wolverine (Toytasktik) 15 GITD Spider-man (Gemini) 40 GITD Unmasked Wolverine (Toytastik) 15 GITD Spider-man (Japan Exc) 41 CA2 Captain America 15 Metallic Spider-man (SDCC 12) 41 CA2 B&W Captain America (BN) 16 Gold Helmet Loki (SDCC 12) 41 CA2 GITD Captain America (HT) 17 Dr. -

Executive Assistants 14

Aspen Splash: 2013 Swimsuit Spectacular 10 : Ember 22 : Grace/Onyx 10th Anniversary Edition by Jonathan Marks & Kyle Ritter by Gabriele Dell’Otto & Peter Steigerwald, Khari Evans & John Starr IFC : Aspen 11 : Aspen 23 : Aspen by Randy Green & Jason Gorder & Beth Sotelo by Billy Tan & John Starr by Oliver Nome & Jordi Escuin llorach 01 : Aspen 12 : Executive Assistants 24 : Kiani by Alex Konat & John Starr by Ryan Odagawa by Philip Tan & Don Ho & Laura Martin 02 : Sudana 13 : Miya 25 : Ange by Vincenzo Cucca & Mirka Andolfo by Nei Ruffino & Beth Sotelo by Micah Gunnell & Rob Stull & Jordi Escuin llorach 03 : Kiori 14 : Aspen/Iris 26 : Grace by Talent Caldwell & John Starr by Scott Clark, Emilio Lopez by Sana Takeda 04 : Molli 15 : Faye 27 : Rachael & Rose by Mike Bowden & David Curiel by Peter Steigerwald by Cory Smith & Stéphan Lemineur 05 : Trish 16/17 : Aspen Jam 28 : Grace/Kiori by Giuseppe Cafaro & Mirka Andolfo by Mike DeBalfo & Peter Steigerwald by Francisco Herrera & Leonardo Olea, Nick Bradshaw & John Starr 06 : Grace 18 : Rose 29 : Aspen by Jason Fabok & Peter Steigerwald by Joe Benitez & Peter Steigerwald by Alé Garza & Beth Sotelo 07 : Sophora 19 : The Death Princess 30 : Ange & Dev by Lori Hanson & Kyle Ritter by Elizabeth Torque by Francis Manapul 08 : Iris/Terra 20 : Kiani 31 : Grace by Marcus To & John Starr, Khary Ranolph & Emilio Lopez by Jordan Gunderson & Stéphan Lemineur by Marco Lorenzana & John Starr 09 : Kiani 21 : Iris 32 : Iris by V. Ken Marion & Wes Hartman by Pasquale Qualano & Stéphan Lemineur by Siya Oum VISIT -

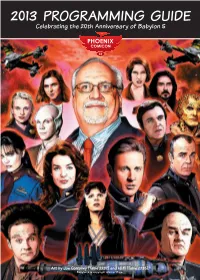

2013 PROGRAMMING GUIDE Celebrating the 20Th Anniversary of Babylon 5

2013 PROGRAMMING GUIDE Celebrating the 20th Anniversary of Babylon 5 Art by Joe Corroney (Table 2237) and Hi Fi (Table 2235). Babylon 5 is copyright Warner Bros. 2 PHOENIX COMICON 2013 • PROGRAMMING GUIDE • PHOENIXCOMICON.COM PHOENIX COMICON 2013 • PROGRAMMING GUIDE • PHOENIXCOMICON.COM 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Hyatt Regency Map .....................................................6 Renaissance Map ...........................................................7 Exhibitor Hall Map .................................................. 8–9 Programming Rooms ........................................... 10–11 Phoenix Comicon Convention Policies .............12 Exhibitor & Artist Alley Locations .............14-15 Welcome to Phoenix Comicon, Guest Locations...........................................................16 Guest Bios .............................................................. 18–22 the signature pop-culture event of Programming Schedule ................................. 24–35 the southwest! Gaming Schedule ..............................................36–42 If you are new to us, or have never been to a “comicon” before, we welcome you. Programming Descriptions.........................44–70 This weekend is the culmination of efforts by over seven hundred volunteers over the past twelve months all with a singular vision of putting on the most fun convention you’ll attend. Festivities kick off Thursday afternoon and continue throughout the weekend. Spend the day checking out the exhibitor hall, meeting actors and writers, buying that hard to -

Heroclix Bestand 16-10-2012

Heroclix Liste Infinity Challenge Infinity Gauntlet Figure Name Gelb Blau Rot Figure Name Gelb Blau Rot Silber und Bronze Adam Warlock 1 SHIELD Agent 1 2 3 Mr. Hyde 109 110 111 Vision 139 In-Betweener 2 SHIELD Medic 4 5 6 Klaw 112 113 114 Quasar 140 Champion 3 Hydra Operative 7 8 9 Controller 115 116 117 Thanos 141 Gardener 4 Hydra Medic 10 11 12 Hercules 118 119 120 Nightmare 142 Runner 5 Thug 13 14 15 Rogue 121 122 123 Wasp 143 Collector 6 Henchman 16 17 18 Dr. Strange 124 125 126 Elektra 144 Grandmaster 7 Skrull Agent 19 20 21 Magneto 127 128 129 Professor Xavier 145 Infinity Gauntlet 101 Skrull Warrior 22 23 24 Kang 130 131 132 Juggernaut 146 Soul Gem S101 Blade 25 26 27 Ultron 133 134 135 Cyclops 147 Power Gem S102 Wolfsbane 28 29 30 Firelord 136 137 138 Captain America 148 Time Gem S103 Elektra 31 32 33 Wolverine 149 Space Gem S104 Wasp 34 35 36 Spider-Man 150 Reality Gem S105 Constrictor 37 38 39 Marvel 2099 Gabriel Jones 151 Mind Gem S106 Boomerang 40 41 42 Tia Senyaka 152 Kingpin 43 44 45 Hulk 1 Operative 153 Vulture 46 47 48 Ravage 2 Medic 154 Jean Grey 49 50 51 Punisher 3 Knuckles 155 Hammer of Thor Hobgoblin 52 53 54 Ghost Rider 4 Joey the Snake 156 Fast Forces Sabretooth 55 56 57 Meanstreak 5 Nenora 157 Hulk 58 59 60 Junkpile 6 Raksor 158 Fandral 1 Puppet Master 61 62 63 Doom 7 Blade 159 Hogun 2 Annihilus 64 65 66 Rahne Sinclair 160 Volstagg 3 Captain America 67 68 69 Frank Schlichting 161 Asgardian Brawler 4 Spider-Man 70 71 72 Danger Room Fred Myers 162 Thor 5 Wolverine 73 74 75 Wilson Fisk 163 Loki 6 Professor Xavier 76 -

Killingly Test 3-30 NEW.Qxt

Mailed free to requesting homes in Brooklyn, the borough of Danielson, Killingly & its villages Vol. II, No. 50 Complimentary home delivery (860) 928-1818/email:[email protected] ‘Life is ours to be spent, not to be saved.’ Friday, November 21, 2008 Four proposed ordinances rejected BY MATT SANDERSON failed were the requirement of VILLAGER STAFF WRITER appropriation statements of agen- BROOKLYN — Two of the seven cies requesting funds, the proposed proposed ordinances passed voter budget reporting structure of the approval at the town meeting Recreation Commission and the Tuesday night, Nov.18, at Brooklyn Board of Fire Commissioners, and Middle School. Approximately 100 the reduction of the Planning and people attended. Zoning Commission members First Selectman Roger Engle said from 10 to seven. the meeting went as expected. He Resident Jeff Otto, who serves as liked the turnout and said voters the liaison for the Board of should be attending all town meet- Finance and the Board of ings in the future, whether the Education, said the appropriations items up for vote on the agenda are ordinance, which asked that no hot topics or not. The proposed ordinances that Turn To ORDINANCES, page A11 Matt Sanderson photo Jared Elam and drop-off site coordinator Adele Thomas, both of Killingly, collect shoeboxes wrapped as presents on Commission accepts Tuesday afternoon at the drop-off site for Operation Christmas Child, a spiritual outreach by the Samaritan Purse orga- nization geared to bring children in desolate countries presents. Wal-Mart application Helping kids have happy holidays BY MATT SANDERSON tion has been scheduled for the VILLAGER STAFF WRITER next Inland Wetlands meeting at 6 BROOKLYN — Wal-Mart’s wet- p.m.