Six Months in Post-Apartheid South Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cape Town's Film Permit Guide

Location Filming In Cape Town a film permit guide THIS CITY WORKS FOR YOU MESSAGE FROM THE MAYOR We are exceptionally proud of this, the 1st edition of The Film Permit Guide. This book provides information to filmmakers on film permitting and filming, and also acts as an information source for communities impacted by film activities in Cape Town and the Western Cape and will supply our local and international visitors and filmmakers with vital guidelines on the film industry. Cape Town’s film industry is a perfect reflection of the South African success story. We have matured into a world class, globally competitive film environment. With its rich diversity of landscapes and architecture, sublime weather conditions, world-class crews and production houses, not to mention a very hospitable exchange rate, we give you the best of, well, all worlds. ALDERMAN NOMAINDIA MFEKETO Executive Mayor City of Cape Town MESSAGE FROM ALDERMAN SITONGA The City of Cape Town recognises the valuable contribution of filming to the economic and cultural environment of Cape Town. I am therefore, upbeat about the introduction of this Film Permit Guide and the manner in which it is presented. This guide will be a vitally important communication tool to continue the positive relationship between the film industry, the community and the City of Cape Town. Through this guide, I am looking forward to seeing the strengthening of our thriving relationship with all roleplayers in the industry. ALDERMAN CLIFFORD SITONGA Mayoral Committee Member for Economic, Social Development and Tourism City of Cape Town CONTENTS C. Page 1. -

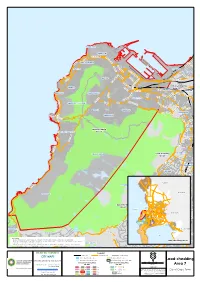

Load-Shedding Area 7

MOUILLE POINT GREEN POINT H N ELEN SUZMA H EL EN IN A SU M Z M A H N C THREE ANCHOR BAY E S A N E E I C B R TIO H A N S E M O L E M N E S SEA POINT R U S Z FORESHORE E M N T A N EL SO N PAARDEN EILAND M PA A A B N R N R D D S T I E E U H E LA N D R B H AN F C EE EIL A K ER T BO-KAAP R T D EN G ZO R G N G A KLERK E E N FW DE R IT R U A B S B TR A N N A D IA T ST S R I AN Load-shedding D D R FRESNAYE A H R EKKER L C Area 15 TR IN A OR G LBERT WOODSTOCK VO SIR LOWRY SALT RIVER O T R A N R LB BANTRY BAY A E TAMBOERSKLOOF E R A E T L V D N I R V R N I U M N CT LT AL A O R G E R A TA T E I E A S H E S ARL K S A R M E LIE DISTRICT SIX N IL F E V V O D I C O T L C N K A MIL PHILIP E O M L KG L SIGNAL HILL / LIONS HEAD P O SO R SAN I A A N M A ND G EL N ON A I ILT N N M TIO W STA O GARDENS VREDEHOEK R B PHILI P KGOSA OBSERVATORY NA F P O H CLIFTON O ORANJEZICHT IL L IP K K SANA R K LO GO E O SE F T W T L O E S L R ER S TL SET MOWBRAY ES D Load-shedding O RH CAMPS BAY / BAKOVEN Area 7 Y A ROSEBANK B L I S N WOO K P LSACK M A C S E D O RH A I R O T C I V RONDEBOSCH TABLE MOUNTAIN Load-shedding Area 5 KLIP PER N IO N S U D N A L RONDEBOSCH W E N D N U O R M G NEWLANDS IL L P M M A A A C R I Y N M L PA A R A P AD TE IS O E R P R I F 14 Swartland RIA O WYNBERG NU T C S I E V D CLAREMONT O H R D WOO BOW Drakenstein E OUDEKRAAL 14 D IN B U R G BISHOPSCOURT H RH T OD E ES N N A N Load-shedding 6 T KENILWORTH Area 11 Table Bay Atlantic 2 13 10 T Ocean R 1 O V 15 A Stellenbosch 7 9 T O 12 L 5 22 A WETTO W W N I 21 L 2S 3 A I A 11 M T E O R S L E N O D Hout Bay 16 4 O V 17 O A H 17 N I R N 17 A D 3 CONSTANTIA M E WYNBERG V R I S C LLANDUDNO T Theewaterskloof T E O 8 L Gordon's R CO L I N L A STA NT Bay I HOUT BAY IA H N ROCKLEY False E M H Bay P A L A I N MAI N IA Please Note: T IN N A G - Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information in this map at the time of puMblication . -

Your Guide to Myciti

Denne West MyCiTi ROUTES Valid from 29 November 2019 - 12 january 2020 Dassenberg Dr Klinker St Denne East Afrikaner St Frans Rd Lord Caledon Trunk routes Main Rd 234 Goedverwacht T01 Dunoon – Table View – Civic Centre – Waterfront Sand St Gousblom Ave T02 Atlantis – Table View – Civic Centre Enon St Enon St Enon Paradise Goedverwacht 246 Crown Main Rd T03 Atlantis – Melkbosstrand – Table View – Century City Palm Ln Paradise Ln Johannes Frans WEEKEND/PUBLIC HOLIDAY SERVICE PM Louw T04 Dunoon – Omuramba – Century City 7 DECEMBER 2019 – 5 JANUARY 2020 MAMRE Poeit Rd (EXCEPT CHRISTMAS DAY) 234 246 Silverstream A01 Airport – Civic Centre Silwerstroomstrand Silverstream Rd 247 PELLA N Silwerstroom Gate Mamre Rd Direct routes YOUR GUIDE TO MYCITI Pella North Dassenberg Dr 235 235 Pella Central * D01 Khayelitsha East – Civic Centre Pella Rd Pella South West Coast Rd * D02 Khayelitsha West – Civic Centre R307 Mauritius Atlantis Cemetery R27 Lisboa * D03 Mitchells Plain East – Civic Centre MyCiTi is Cape Town’s safe, reliable, convenient bus system. Tsitsikamma Brenton Knysna 233 Magnet 236 Kehrweider * D04 Kapteinsklip – Mitchells Plain Town Centre – Civic Centre 245 Insiswa Hermes Sparrebos Newlands D05 Dunoon – Parklands – Table View – Civic Centre – Waterfront SAXONSEAGoede Hoop Saxonsea Deerlodge Montezuma Buses operate up to 18 hours a day. You need a myconnect card, Clinic Montreal Dr Kolgha 245 246 D08 Dunoon – Montague Gardens – Century City Montreal Lagan SHERWOOD Grosvenor Clearwater Malvern Castlehill Valleyfield Fernande North Brutus -

Cape Town Townships Cultural Experience

FULL DAY TOURS The below tours are not part of the conference package. Bookings should be made directly to Scatterlings Conference & Events and not via the FSB/OECD office. Cape Town Townships Cultural Experience Enjoy the multi - cultural life of the Cape by meeting and speaking to the local communities on our full day Cape Town Township Tour. Interact with locals in their own living environments and experience the multi- diversity of our sought after city. Highlights: Bo-Kaap and exciting Malay Quarter; District Six Museum; Cape Flats; Visit a traditional shop (spaza) or tavern (shebeen) in a township; Take a ferry trip to Robben Island and walk through the former political prison (weather permitting). Click here to send your enquiry: [email protected] Aquila Game Reserve Travel through Huguenot Tunnel past beautiful De Doorns in the Hex River valley to Aquila. Welcoming refreshments, game drive, bushman paintings and lunch in an outdoor lapa. Stroll through curio and wine shop, or relax at pool before returning to Cape Town. Click here to send your enquiry: [email protected] Cape Peninsula Travel along the beautiful coastline of the Peninsula on our Cape Peninsula day tour, through historic and picturesque villages to the mythical meeting place of the two great oceans. Highlights: Travel through Sea Point, Clifton and Camps Bay; Hout Bay Harbour (optional Seal Island boat trip, not included in cost); On to Cape Point and Nature Reserve. Unforgettable plant, bird and animal life; Lunch at Cape Point; Penguin Colony; Historic Simonstown; Groot Constantia wine estate or Kirstenbosch Botanical Gardens. Click here to send your enquiry: [email protected] Cape Winelands On our Cape Winelands day tour we take you on a trip into the heart of the Cape Winelands, through breathtaking mountain ranges and fertile valleys. -

Fire & Ice Cape Town Factsheet

New Church & Buitensingel Street, Tamboerskloof Cape Town 8018, South Africa Tel: +27 (0) 21 488 2555 FACT SHEET Fax: +27 (0) 21 488 2556 Email: [email protected] proteahotels.com/fireandice DISTANCE LOCATION FROM HOTEL 200 M LONG STREET VIBEY RESTAURANTS & BARS 1 KM CAPE TOWN CITY CENTRE TAMBOERSKLOOF, CAPE TOWN 1.6 KM CAPE TOWN RAILWAY STATION 2 KM CAPE TOWN INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION CENTRE 4.1 KM TABLE MOUNTAIN CABLE CAR 4.3 KM V&A WATERFRONT SHOPPING CENTRE 4.7 KM CAMPS BAY AND CLIFTON BEACHES 11.3 KM RONDEBOSCH GOLF CLUB 12.7 KM CANAL WALK, CENTURY CITY SHOPPING CENTRE 19.8 KM CAPE TOWN INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT 201 ROOMS MODERN, UPMARKET BEDROOMS IN-ROOM FACILITIES TEA & COFFEE AIR-CONDITIONED ELECTRONIC LAPTOP- MAKING-FACILITIES FRIENDLY SAFES 85 STANDARD ROOMS 97 24 HOURS IRON ON LCD FLAT SCREEN SUPERIOR ROOMS ROOM SERVICE REQUEST BATHROOM BOSE RADIO EXECUTIVE AMENITIES ALARM CLOCK WORK DESK MINIBAR FRIDGE (EXECUTIVE 1 & 2 7 6 6 BEDROOM SUITES) SUPERIOR PATIO EXECUTIVE 1 EXECUTIVE 2 ROOMS BEDROOM BEDROOM SUITE SUITE HOTEL FACILITIES FOOD & BEVERAGE & SERVICES SERVICE TIMES 500MB PER DAY HEATED POOL WITH GYM TRENDY BAR 06H30 FREE WI-FI EXTRAORDINARY BREAKFAST POOL DECK 10H30 12H30 LUNCH 16H00 SECURE LAUNDRY TRAVEL AND CONFERENCE UNDERGROUND SERVICE ADVENTURE FACILITIES PARKING CENTRE 18H30 DINNER 22H30 SPA ULTRA CHIC RESTAURANT BOARDROOMS & CONFERENCE ROOMS NEARBY ENTERTAINMENT GROUND WORK 1 BREAKTHROUGH ON 2 THE LAUNCH PAD 140 M2 72 M2 344 M2 90 60 200 DELEGATES DELEGATES DELEGATES (COCKTAIL STYLE) (COCKTAIL STYLE) (COCKTAIL -

Cape Town 2021 Touring

CAPE TOWN 2021 TOURING Go Your Way Touring 2 Pre-Booked Private Touring Peninsula Tour 3 Peninsula Tour with Sea Kayaking 13 Winelands Tour 4 Cape Canopy Tour 13 Hiking Table Mountain Park 14 Suggested Touring (Flexi) Connoisseur's Winelands 15 City, Table Mountain & Kirstenbosch 5 Cycling in the Winelands & visit to Franschhoek 15 Cultural Tour - Robben Island & Kayalicha Township 6 Fynbos Trail Tour 16 Jewish Cultural & Table Mountain 7 Robben Island Tour 16 Constantia Winelands 7 Cape Malay Cultural Cooking Experience 17 Grand Slam Peninsula & Winelands 8 “Cape Town Eats” City Walking Tour 17 West Coast Tour 8 Cultural Exploration with Uthando 18 Hermanus Tour 9 Cape Grace Art & Antique Tour 18 Shopping & Markets 9 Group Scheduled Tours Whale Watching & Shark Diving Tours Group Peninsula Tour 19 Dyer Island 'Big 5' Boat Ride incl. Whale Watching 10 Group Winelands Tour 19 Gansbaai Shark Diving Tour 11 Group City Tour 19 False Bay Shark Eco Charter 12 Touring with Families Family Peninsula Tour 20 Family Fun with Animals 20 Featured Specialist Guides 21 Cape Town Touring Trip Reports 24 1 GO YOUR WAY – FULL DAY OR HALF DAY We recommend our “Go Your Way” touring with a private guide and vehicle and then customizing your day using the suggested tour ideas. Cape Town is one of Africa’s most beautiful cities! Explore all that it offers with your own personalized adventure with amazing value that allows a day of touring to be more flexible. RATES FOR FULL DAY or HALF DAY– GO YOUR WAY Enjoy the use of a vehicle and guide either for a half day or a full day to take you where and when you want to go. -

Things to Do in Cape Town NUMBER 1: Robben Island

Things to Do in Cape Town NUMBER 1: Robben Island Price: adult (R250); children under 18 (R120) The standard tour to Robben Island is 3.5 hours long, including the two half-hour ferry rides. Ferries depart at 9am, 11am, 1pm and 3pm everyday (weather permitting) from the V & A Waterfront in Cape Town. The summer season is very busy and we recommend you book early to avoid disappointment! Booking a minimum of three days in advance is recommended. To book tickets: Website: www.robben-island.org.za Call: 021 413 4220/1 (Robben Island Museum); 021 413 4233 / 37 (Advanced Booking) Email: [email protected] The ticket sales office is located at the Nelson Mandela Gateway at the V&A Waterfront, Cape Town. Once you have completed your trip, you may wish to indulge in a bit of shopping or have a relaxing lunch at one of the many restaurants situated at the Waterfront on the harbour. NUMBER 2: Table Mountain Price: Cable car (Return and one way tickets available) Adult: Return: R205 Children (4 – 17 years): Return: R100 Children (Under 4): Free Sunset special: For the month of January, return tickets after 18h00 will be half price and can be bought only from the ticket office at the Lower Cable Station after 18h00. One can either cable car or walk up to reach the top of the mountain. The cable car goes up every 15 minutes, so you don’t need to worry about catching one. However you will need to take note of the weather. -

Water Services and the Cape Town Urban Water Cycle

WATER SERVICES AND THE CAPE TOWN URBAN WATER CYCLE August 2018 WATER SERVICES AND THE CAPE TOWN URBAN WATER CYCLE TABLE OF CONTENTS WATER SERVICES AND THE CAPE TOWN URBAN WATER CYCLE ...................................... 3 1. EVAPORATION ................................................................................................................ 5 2. CONDENSATION ............................................................................................................. 5 3. PRECIPITATION ............................................................................................................... 6 4. OUR CATCHMENT AREAS ............................................................................................. 7 5. CAPE TOWN’S DAMS ...................................................................................................... 9 6. WHAT IS GROUNDWATER? ......................................................................................... 17 7. SURFACE RUNOFFS ..................................................................................................... 18 8. CAPE TOWN’S WATER TREATMENT WORKS ............................................................ 19 9. CAPE TOWN’S RESERVOIRS ....................................................................................... 24 10. OUR RETICULATION SYSTEMS ................................................................................... 28 11. CONSUMERS .................................................................................................................. -

Dispossession, Displacement, and the Making of the Shared Minibus Taxi in Cape Town and Johannesburg, South Africa, 1930-Present

Sithutha Isizwe (“We Carry the Nation”): Dispossession, Displacement, and the Making of the Shared Minibus Taxi in Cape Town and Johannesburg, South Africa, 1930-Present A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Elliot Landon James IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Allen F. Isaacman & Helena Pohlandt-McCormick November 2018 Elliot Landon James 2018 copyright Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................. ii List of Abbreviations ......................................................................................................iii Prologue .......................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1 ....................................................................................................................... 17 Introduction: Dispossession and Displacement: Questions Framing Thesis Chapter 2 ....................................................................................................................... 94 Historical Antecedents of the Shared Minibus Taxi: The Cape Colony, 1830-1930 Chapter 3 ..................................................................................................................... 135 Apartheid, Forced Removals, and Public Transportation in Cape Town, 1945-1978 Chapter 4 .................................................................................................................... -

Beaches a Diversity of Coastal Treasures CITY of CAPE TOWN BEACHES

CITY OF CAPE TOWN Beaches A diversity of coastal treasures CITY OF CAPE TOWN BEACHES Published by the City of Cape Town First edition 2009 More information available from: Environmental Resource Management Department 7th Floor 44 Wale Street Cape Town Tel: 021 487 2284 www.capetown.gov.za/environment ISBN 978-0-9802784-3-9 This handbook is printed on SAPPI Triple Green paper, an environmentally-friendly paper stock made from chlorine-free sugar cane fibre to support sustainable afforestation in South Africa. Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information in this book at the time of publication and to correctly acknowledge photographs. The City of Cape Town accepts no responsibility for, and will not be liable for, any errors or omissions contained herein. CITY OF CAPE TOWN Beaches A diversity of coastal treasures Contents 1 CAPE TOWN’S TWO COASTS 41 CITY SEABOARD 2 Upwelling 42 Granger Bay 3 Tides 43 Mouille Point 4 Rocky shores 44 Three Anchor Bay 6 Sandy beaches 45 Sea Point 8 Estuaries – Rocklands 10 Blue Flag – Graaff’s Pool 11 Shark-spotting programme – Milton Beach 12 Whale-watching – Brokenbath Beach 14 Threats to the coastal zone – Sunset Beach 18 Harvesting marine resources – Queen’s Beach 20 Sustainable seafood – Saunders’ Rocks – Consumer’s Seafood Species List 49 Bantry Bay 22 Early days on the Cape coast 49 Clifton –1st Beach 27 WEST COAST –2nd Beach 28 Silwerstroomstrand –3rd Beach 29 Van Riebeeckstrand –4th Beach – Duynefontein 52 Maiden’s Cove 30 Melkbosstrand 52 Camps Bay 32 Blaauwberg Conservation Area -

A Neighborhood in Change

A neighborhood in change A case study on gentrification in Bo-Kaap, Cape Town Emilia Lundqvist & Matilda Pettersson Stadsbyggnad, stadsutveckling och planering / Urban Development and Planning. Kandidatuppsats, 20 HP Vårterminen 2020 Handledare: Defne Kadioglu 1 A special thanks to SIDA for providing us with a scholarship that made it possible for us to do our research in South Africa. Thanks to Hoai Anh Tran for supporting us when applying for the scholarship. And the biggest thanks to our supervisor Defne Kadioglu for providing us with much needed help during our difficult times. Our original plan was to do an 8 weeklong case study in Bo-Kaap, but because of Covid-19 and the impact that the pandemic has had on both the Swedish and the South African societies, this has affected our case study. We were forced to leave South Africa five weeks prior to our original plan. Because of this we had to make several of our interviews online which may have affected our end result. 2 Abstract When neighborhoods and cities fall in decline, cities and investors see an opportunity to turn the declining sites into profitable new projects, this happens all over the world in different renewal projects, or under the term gentrification. The outcome of gentrification can be considered to be both positive and negative, and the term is widely discussed in today's media. This study aims to get an understanding of how a small neighborhood in Cape Town called Bo-Kaap, that is famous for its rich culture and strong community, is affected by investors wanting to develop the neighborhood. -

Beach Zones for Dogs & Horses

BEACH ZONES FOR DOGS & HORSES BEACHES DOG HORSE BEACHES DOG HORSE (A - H) ZONE ZONE (K - W) ZONE ZONE All tidal pools No dogs No horses Kogel Bay Resort No dogs No horses Bakoven Beach No dogs No horses Kreeftebaai No dogs No horses Beta Beach No dogs No horses Lagoon Beach, Milnerton Dogs free running No horses Big Bay No dogs No horses Llandudno No dogs during 09:00-18:00 No horses Bikini Beach No dogs No horses in November-March, and free running at all other Blaauwberg No dogs No horses times. Blue Waters Resort No dogs No horses Long Beach, Kommetjie Dogs free running No horses Broken Bath No dogs No horses Long Beach, Simon's Town Dogs free running No horses Burghers' Walk Dogs on a leash No horses Macassar Resort No dogs No horses Camps Bay Beach No dogs during 09:00-18:00 in No horses Maiden's Cove No dogs No horses November-March, free-running st th st th at all other times; No dogs at all Melkbosstrand 1 to 5 1 Ave to 5 Ave dogs on a No horses times in the Tidal Pool and Blue Avenues leash between 07:00 and 17:00; Flag areas. dogs free running between 17:00 and 07:00. Cayman Beach No dogs No horses Melkbosstrand Main 1 December - 31 March: no No horses st Clifton 1 Dogs free running No horses Beach from 5th Avenue to dogs between 09:00 and 19:00, Clifton 2nd No dogs November - March, No horses Slabbert se Klippe dogs on a leash between free-running at all other times.