Atoll Research Bulletin No. 183 Ducie Atoll

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gates, Edward Harmon (1855–1940)

Mrs. E.H. Gates, Mrs. J.I. Tay, E.H. Gates, J.I. Tay, and A.J. Cudney Photo courtesy of the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists Archives. Gates, Edward Harmon (1855–1940) MILTON HOOK Milton Hook, Ed.D. (Andrews University, Berrien Springs, Michigan, the United States). Hook retired in 1997 as a minister in the Greater Sydney Conference, Australia. An Australian by birth Hook has served the Church as a teacher at the elementary, academy and college levels, a missionary in Papua New Guinea, and as a local church pastor. In retirement he is a conjoint senior lecturer at Avondale College of Higher Education. He has authoredFlames Over Battle Creek, Avondale: Experiment on the Dora, Desmond Ford: Reformist Theologian, Gospel Revivalist, the Seventh-day Adventist Heritage Series, and many magazine articles. He is married to Noeleen and has two sons and three grandchildren. Edward H. Gates was a prominent leader in early Seventh-day Adventist mission work in the Pacific Islands and Southeast Asia. Early Life and Ministry Edward Harmon Gates was born on April 1, 1855, in the rural village of Munson, east of Cleveland, Ohio. He joined the Seventh-day Adventist church when he was approximately nineteen years of age as a result of reading various tracts and the Advent Review and Sabbath Herald. He began preaching in Ohio and was ordained in 1879. To improve his understanding of Scripture he attended Battle Creek College1 where he met Ida Ellen Sharpe.2 They married in Battle Creek on February 22, 1881, Uriah Smith conducting the service.3 -

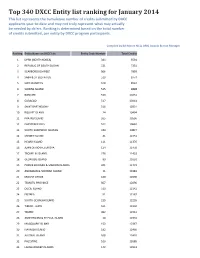

Top 340 DXCC Entity List Ranking for January 2014

Top 340 DXCC Entity list ranking for January 2014 This list represents the cumulative number of credits submitted by DXCC applicants year‐to‐date and may not truly represent what may actually be needed by dx'ers. Ranking is determined based on the total number of credits submitted, per entity by DXCC program participants. Compiled by Bill Moore NC1L ARRL Awards Branch Manager Ranking Entity Name on DXCC List Entity Code Number Total Credits 1DPRK (NORTH KOREA) 344 5591 2REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN 521 7231 3SCARBOROUGH REEF 506 7893 4SABA & ST EUSTATIUS 519 8774 5SINT MAARTEN 518 8967 6SWAINS ISLAND 515 9898 7 BONAIRE 520 10251 8 CURACAO 517 10314 9SAINT BARTHELEMY 516 10354 10 BOUVET ISLAND 24 10494 11 PRATAS ISLAND 505 10596 12 CHESTERFIELD IS. 512 10663 13 SOUTH SANDWICH ISLANDS 240 10827 14 CROZET ISLAND 41 11351 15 HEARD ISLAND 111 11376 16 JUAN DE NOVA, EUROPA 124 11450 17 TROMELIN ISLAND 276 11453 18 GLORIOSO ISLAND 99 11691 19 PRINCE EDWARD & MARION ISLANDS 201 11772 20 ANDAMAN & NICOBAR ISLAND 11 11981 21 MOUNT ATHOS 180 12090 22 TEMOTU PROVINCE 507 12096 23 DUCIE ISLAND 513 12142 24 ERITREA 51 12167 25 SOUTH GEORGIA ISLAND 235 12220 26 TIMOR ‐ LESTE 511 12250 27 YEMEN 492 12314 28 AMSTERDAM & ST PAUL ISLAND 10 12342 29 MACQUARIE ISLAND 153 12367 30 NAVASSA ISLAND 182 12460 31 AUSTRAL ISLAND 508 12493 32 PALESTINE 510 12685 33 LAKSHADWEEP ISLANDS 142 12913 Ranking Entity Name on DXCC List Entity Code Number Total Credits 34 MARQUESAS ISLAND 509 12944 35 KINGMAN REEF 134 12990 36 ANNOBON 195 13391 37 PETER 1 ISLAND 199 13701 38 SAINT -

Zootaxa,Lovell Augustus Reeve (1814?865): Malacological Author and Publisher

ZOOTAXA 1648 Lovell Augustus Reeve (1814–1865): malacological author and publisher RICHARD E. PETIT Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Richard E. Petit Lovell Augustus Reeve (1814–1865): malacological author and publisher (Zootaxa 1648) 120 pp.; 30 cm. 28 November 2007 ISBN 978-1-86977-171-3 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-86977-172-0 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2007 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41-383 Auckland 1346 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2007 Magnolia Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed in writing. This authorization does not extend to any other kind of copying, by any means, in any form, and for any purpose other than private research use. ISSN 1175-5326 (Print edition) ISSN 1175-5334 (Online edition) 2 · Zootaxa 1648 © 2007 Magnolia Press PETIT Zootaxa 1648: 1–120 (2007) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2007 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Lovell Augustus Reeve (1814–1865): malacological author and publisher RICHARD E. PETIT 806 St. Charles Road, North Myrtle Beach, SC 29582-2846, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Table of contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................................................4 -

Shyama Pagad Programme Officer, IUCN SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group

Final Report for the Ministry of Environment, Lands and Agricultural Development Compile and Review Invasive Alien Species Information Shyama Pagad Programme Officer, IUCN SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group 1 Table of Contents Glossary and Definitions ................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 4 SECTION 1 ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Alien and Invasive Species in Kiribati .............................................................................................. 7 Key Information Sources ................................................................................................................. 7 Results of information review ......................................................................................................... 8 SECTION 2 ..................................................................................................................................... 10 Pathways of introduction and spread of invasive alien species ................................................... 10 SECTION 3 ..................................................................................................................................... 12 Kiribati and its biodiversity .......................................................................................................... -

Background the Capital, Suva, Is on the Southeastern Shore of Viti Levu

Fiji Islands Photo courtesy of Barry Oliver. Fiji MILTON HOOK Milton Hook, Ed.D. (Andrews University, Berrien Springs, Michigan, the United States). Hook retired in 1997 as a minister in the Greater Sydney Conference, Australia. An Australian by birth Hook has served the Church as a teacher at the elementary, academy and college levels, a missionary in Papua New Guinea, and as a local church pastor. In retirement he is a conjoint senior lecturer at Avondale College of Higher Education. He has authoredFlames Over Battle Creek, Avondale: Experiment on the Dora, Desmond Ford: Reformist Theologian, Gospel Revivalist, the Seventh-day Adventist Heritage Series, and many magazine articles. He is married to Noeleen and has two sons and three grandchildren. Fiji consists of approximately 330 islands in the mid-South Pacific Ocean, the largest being Viti Levu and Vanua Levu. Background The capital, Suva, is on the southeastern shore of Viti Levu. Fifty-four percent of the population are indigenous Fijians (Melanesians), and forty percent are descendants of Hindu Indian laborers originally brought in to work on the sugar cane plantations. There is a small percentage of people of Polynesian descent in the eastern islands.1 Among the early Europeans to enter Fijian waters were Abel Tasman (1643) and James Cook (1774). Methodist missionaries arrived in the nineteenth century and established a Christian base, having converted influential chiefs who, in turn led their clans to accept the faith together with many Western social mores. The country became a British crown colony in 1894 and gained its independence in 1970. Friction has developed between the indigenous Fijians and Indo- Fijians, the indigenous chiefs gaining the upper hand with sole land rights under a republican government since 1987.2 Arrival of Seventh-day Adventists The missionary ship “Pitcairn” reached Suva, Fiji, on August 3, 1891. -

US Fish & Wildlife Service Seabird Conservation Plan—Pacific Region

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Seabird Conservation Plan Conservation Seabird Pacific Region U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Seabird Conservation Plan—Pacific Region 120 0’0"E 140 0’0"E 160 0’0"E 180 0’0" 160 0’0"W 140 0’0"W 120 0’0"W 100 0’0"W RUSSIA CANADA 0’0"N 0’0"N 50 50 WA CHINA US Fish and Wildlife Service Pacific Region OR ID AN NV JAP CA H A 0’0"N I W 0’0"N 30 S A 30 N L I ort I Main Hawaiian Islands Commonwealth of the hwe A stern A (see inset below) Northern Mariana Islands Haw N aiian Isla D N nds S P a c i f i c Wake Atoll S ND ANA O c e a n LA RI IS Johnston Atoll MA Guam L I 0’0"N 0’0"N N 10 10 Kingman Reef E Palmyra Atoll I S 160 0’0"W 158 0’0"W 156 0’0"W L Howland Island Equator A M a i n H a w a i i a n I s l a n d s Baker Island Jarvis N P H O E N I X D IN D Island Kauai S 0’0"N ONE 0’0"N I S L A N D S 22 SI 22 A PAPUA NEW Niihau Oahu GUINEA Molokai Maui 0’0"S Lanai 0’0"S 10 AMERICAN P a c i f i c 10 Kahoolawe SAMOA O c e a n Hawaii 0’0"N 0’0"N 20 FIJI 20 AUSTRALIA 0 200 Miles 0 2,000 ES - OTS/FR Miles September 2003 160 0’0"W 158 0’0"W 156 0’0"W (800) 244-WILD http://www.fws.gov Information U.S. -

075 Phoenix Petrel

Text and images extracted from Marchant, S. & Higgins, P.J. (co-ordinating editors) 1990. Handbook of Australian, New Zealand & Antarctic Birds. Volume 1, Ratites to ducks; Part A, Ratites to petrels. Melbourne, Oxford University Press. Pages 263-264, 355-356, 445-447; plate 30. Reproduced with the permission of Bird life Australia and Jeff Davies. 263 Order PROCELLARIIFORMES A rather distinct group of some 80-100 species of pelagic seabirds, ranging in size from huge to tiny and in habits from aerial (feeding in flight) to aquatic (pursuit-diving for food), but otherwise with similar biology. About three-quarters of the species occur or have been recorded in our region. They are found throughout the oceans and most come ashore voluntarily only to breed. They are distinguished by their hooked bills, covered in horny plates with raised tubular nostrils (hence the name Tubinares). Their olfactory systems are unusually well developed (Bang 1966) and they have a distinctly musky odour, which suggest that they may locate one another and their breeding places by smell; they are attracted to biogenic oils at sea, also no doubt by smell. Probably they are most closely related to penguins and more remotely to other shorebirds and waterbirds such as Charadrii formes and Pelecaniiformes. Their diversity and abundance in the s. hemisphere suggest that the group originated there, though some important groups occurred in the northern hemisphere by middle Tertiary (Brodkorb 1963; Olson 1975). Structurally, the wings may be long in aerial species and shorter in divers of the genera Puffinus and Pel ecanoides, with 11 primaries, the outermost minute, and 10-40 secondaries in the Oceanitinae and great albatrosses respectively. -

Hugh Cuming (1791-1865) Prince of Collectors by S

J. Soc. Biblphy not. Hist. (1980) 9 (4): 477-501 Hugh Cuming (1791-1865) Prince of collectors By S. PETER DANCE South Bank House, Broad Street, Hay-on-Wye, Powys INTRODUCTION A combination of superabundant energy, unquenchable enthusiasm and endless opportunity was responsible for the remarkable increase in our knowledge of the natural world during the nineteenth century. For every man of action prepared to risk his life in foreign parts there was a dozen armchair students eager to publish descriptions and illustrations of the plants and animals he brought home. Among nineteenth-century men of action few con- tributed as much to the material advance of natural history as Hugh Cuming (1791 —1865) and none has received such an unequal press. A widely accepted picture of the man is contained in a popular and much acclaimed book1 published in the 1930s: The research after the rare, a quasi-commercial, quasi-scientific research, is typified, glorified and carried to the point of exhausting the fun of the game, in the career of the excellent Englishman Hugh Cuming, a wealthy amateur, who set out in a private yacht to cruise the world for new shells, some- thing to tickle the jaded fancy of the European collector in his castle or parsonage or shell-shop. In the Philippines Cuming sent native collectors into the jungles after tropical tree snails, and saw one fellow returning with a sack full from which specimens (every one possibly a genus new to science) were dribbling carelessly along the jungle floor. On a reef in the South Seas (which has since been destroyed by a hurricane) he came on eight living shells of the 'Glory-of-the-Sea'. -

Explorers Voyage

JANUARY 2021 EXPLORERS VOYAGE TOUR HIGHLIGHTS A LEGENDARY SEA VOYAGE AND LANDED VISITS TO ALL FOUR ISLANDS STARGAZING IN MATA KI TE RANGI 'EYES TO THE SKY' INTERNATIONAL DARK SKY SANCTUARY UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE SITE, HENDERSON ISLAND EXPLORING THE 3RD LARGEST MARINE RESERVE ON EARTH FIRSTHAND INSIGHT INTO LIVING HISTORY AND CULTURE JANUARY 2021 PITCAIRN ISLANDS EXPLORERS VOYAGE A rare journey to Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie & Oeno Pitcairn Islands Tourism and Far and Away Adventures are pleased to present a 2021 small group Explorers Voyage to Oeno, Pitcairn, Ducie, and Henderson Island. Lying in the central South Pacific, the islands of Henderson, Ducie and Oeno support remarkably pristine habitats and are rarely visited by non-residents of Pitcairn. Pitcairn Islands This will be the second ever voyage of its Group kind — visiting all four of the islands in the Pitcairn Islands Group! . The 18-night/19-day tour includes 11-days cruising around the remote Pitcairn Islands group, stargazing in Pitcairn's new International Dark Sky Sanctuary named Mata ki te Rangi meaning 'Eyes To the Sky', exploring the world’s third largest marine reserve, landings on UNESCO World Heritage site Henderson Island and seldom visited Oeno and Ducie Island, as well as a 4-day stay on Pitcairn Island, during Bounty Day 2021, home of the descendants of the HMAV Bounty mutineers since 1790. JANUARY 2021 PITCAIRN ISLANDS EXPLORERS VOYAGE About the Pitcairn Islands Group The Pitcairn Islands Group forms the UK’s only Overseas Territory in the vast Pacific Ocean. With a total population of 50 residents and located near the centre of the planet’s largest ocean, the isolation of the Pitcairn Islands is truly staggering. -

Gilbertese and Ellice Islander Names for Fishes and Other Organisms

Gilbertese and Ellice Islander Names for Fishes and Other Organisms PHIL S. LOBEL Museum of Comparative Zoology Har vard University Cambridge. Massachusel/s 02138 Abstract.- A compilation of 254 Gilbertese and 153 Ellice Island~r fish names is given which includes names for species from sixty families of fishes. The Gilbertese names (25) and Ellice Islander names ( 17) are also given for anatomical parts of fishes. Gilbertese names for lizards (3), marine invertebrates (95) and algae (2) are listed. The names were compiled from the literature and from interviews with Gilbertese and Ellice Islander fisherman living on Fanning Island in the Line Islands. Introduction Names used by Pacific Islanders for fishes are well known only for Hawaiians (Titcomb, 1953), Tahitians (Randall, 1973) and Palauans (Helfman and Randall, 1973). Banner and Randall (1952) and Randall (1955) have reported some Gilbertese names for invertebrates and fishes, but these were relatively few. A listing ofGilbertese names for plants and animals was compiled from the literature by Goo and Banner ( 1963), but unfortunately this work was never published. To my knowledge, no lists of Ellice Islander names have yet been published. I have compiled the common names used by the people of Fanning Atoll, Line Islands. The people are of Gilbertese and Ellice Islander descent having been brought to the Atoll within the last 50 years to work for the copra plantation. In addition, I have included previously published names to make this listing as complete as possible. I add about 200 new Gilbertese and 150 Ellice Islander names. I have not included names for terrestrial plants (see Moul 1957 for these). -

Monitoring Functional Groups of Herbivorous Reef Fishes As Indicators of Coral Reef Resilience a Practical Guide for Coral Reef Managers in the Asia Pacifi C Region

Monitoring Functional Groups of Herbivorous Reef Fishes as Indicators of Coral Reef Resilience A practical guide for coral reef managers in the Asia Pacifi c Region Alison L. Green and David R. Bellwood IUCN RESILIENCE SCIENCE GROUP WORKING PAPER SERIES - NO 7 IUCN Global Marine Programme Founded in 1958, IUCN (the International Union for the Conservation of Nature) brings together states, government agencies and a diverse range of non-governmental organizations in a unique world partnership: over 100 members in all, spread across some 140 countries. As a Union, IUCN seeks to influence, encourage and assist societies throughout the world to conserve the integrity and diversity of nature and to ensure that any use of natural resources is equitable and ecologically sustainable. The IUCN Global Marine Programme provides vital linkages for the Union and its members to all the IUCN activities that deal with marine issues, including projects and initiatives of the Regional offices and the six IUCN Commissions. The IUCN Global Marine Programme works on issues such as integrated coastal and marine management, fisheries, marine protected areas, large marine ecosystems, coral reefs, marine invasives and protection of high and deep seas. The Nature Conservancy The mission of The Nature Conservancy is to preserve the plants, animals and natural communities that represent the diversity of life on Earth by protecting the lands and waters they need to survive. The Conservancy launched the Global Marine Initiative in 2002 to protect and restore the most resilient examples of ocean and coastal ecosystems in ways that benefit marine life, local communities and economies. -

DXCC Entity Prefix Confirm. Needed Grid Square.Rev: 7/30/21 Cont. Sov

confirm. DXCC Entity Prefix Grid Square.rev: 7/30/21 Cont. needed Sov. Mil. Order of 1A0 1 JM75 EU Malta Monaco 3A 1 JN33 EU Agalega & St.Brandon 3B6,7 1 LH89 AF Mauritius 3B8 1 LG89 AF Rodriguez Is. 3B9 1 MH10 AF Equatorial Guinea 3C 1 JJ41, 51 AF Annobon Is. 3C0 1 JI28 AF Fiji 3D2/f 3 RH81-83, 90-93, AH01-03 OC Conway Reef 3D2/c 1 RG78 OC Rotuma Is. 3D2/r 1 RH87 OC Swaziland 3DA 2 KG52-54, 62-63 AF 3DA after eSwatini 2 KG52-54, 62-63 AF 18Apr2018 Tunisia 3V 2 JM33-34, 40-47, 50-57 AF OJ28-29, 39, OK20-21, 27-38, 40-46, Vietnam 3W, XV 4 AS OL00-01, 10-12, 20 IJ39, 48-49, 57-59, IK20-21, 30-32, 40-42, Guinea 3X 2 AF 50-52 Bouvet 3Y 1 JD15 AF Peter 1 Is. 3Y 1 EC41 AN LM 28-29, 38-39, 48-49, LN 20-21, 30-31. Azerbaijan 4J, 4K 3 AS 40-41, 50 Georgia 4L 3 LN 01-03, 11-13, 21-22, 31-32 AS Montenegro 4O after 28Jun2006 1 JN 91-93, KN 02-03 EU Sri Lanka 4P-4S 2 MJ 96-99, NJ 06-09 AS ITU HQ 4U_ITU (Geneva) 1 JN 36 EU 4U_UN United Nations HQ 1 FN 30 NA (New York) Timor-Leste 4W 1 PI 20-21, 30-31 OC Israel 4X, 4Z 3 KL 79, KM 70-73 AS JL 45-49, 53-59, 63-69, 72-79, 83-89, 91-99, JM 40, 50-52, 60-62, 70-72, 80-81, 90, KL Libya 5A 2 AF 00-09, 10-19, 20-29, KM 00-02, 10-12, 20- 21 Cyprus 5B 2 KM 64-65, 74-75 AS KH 78-89, 98-99, KI 43-45, 51-58, 60-67, Tanzania 5H-5I 3 AF 70-78, 80-87, 90-95 JJ 16-19, 24-29, 34-39, 44-49, 56-59, 68-69, Nigeria 5N-5O 3 JK 10-11, 20-23, 30-33, 40-43, 50-53, 60- AF 63, 71-72 LG 15-19, 24-29, 34-39, 47-49, LH 12, 20- Madagascar 5R-5S 2 AF 24, 30-36, 40-48, 53-56 Mauritania 5T 2 IK 16-19, 26-29, 34-39, 45-49, 55-59, 65-69,