Habeas Corpus Procedure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stapylton Final Version

1 THE PARLIAMENTARY PRIVILEGE OF FREEDOM FROM ARREST, 1603–1629 Keith A. T. Stapylton UCL Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 Page 2 DECLARATION I, Keith Anthony Thomas Stapylton, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed Page 3 ABSTRACT This thesis considers the English parliamentary privilege of freedom from arrest (and other legal processes), 1603-1629. Although it is under-represented in the historiography, the early Stuart Commons cherished this particular privilege as much as they valued freedom of speech. Previously one of the privileges requested from the monarch at the start of a parliament, by the seventeenth century freedom from arrest was increasingly claimed as an ‘ancient’, ‘undoubted’ right that secured the attendance of members, and safeguarded their honour, dignity, property, and ‘necessary’ servants. Uncertainty over the status and operation of the privilege was a major contemporary issue, and this prompted key questions for research. First, did ill definition of the constitutional relationship between the crown and its prerogatives, and parliament and its privileges, lead to tensions, increasingly polemical attitudes, and a questioning of the royal prerogative? Where did sovereignty now lie? Second, was it important to maximise the scope of the privilege, if parliament was to carry out its business properly? Did ad hoc management of individual privilege cases nevertheless have the cumulative effect of enhancing the authority and confidence of the Commons? Third, to what extent was the exploitation or abuse of privilege an unintended consequence of the strengthening of the Commons’ authority in matters of privilege? Such matters are not treated discretely, but are embedded within chapters that follow a thematic, broadly chronological approach. -

THE LEGACY of the MAGNA CARTA MAGNA CARTA 1215 the Magna Carta Controlled the Power Government Ruled with the Consent of Eventually Spreading Around the Globe

THE LEGACY OF THE MAGNA CARTA MAGNA CARTA 1215 The Magna Carta controlled the power government ruled with the consent of eventually spreading around the globe. of the King for the first time in English the people. The Magna Carta was only Reissues of the Magna Carta reminded history. It began the tradition of respect valid for three months before it was people of the rights and freedoms it gave for the law, limits on government annulled, but the tradition it began them. Its inclusion in the statute books power, and a social contract where the has lived on in English law and society, meant every British lawyer studied it. PETITION OF RIGHT 1628 Sir Edward Coke drafted a document King Charles I was not persuaded by By creating the Petition of Right which harked back to the Magna Carta the Petition and continued to abuse Parliament worked together to and aimed to prevent royal interference his power. This led to a civil war, and challenge the King. The English Bill with individual rights and freedoms. the King ultimately lost power, and his of Rights and the Constitution of the Though passed by the Parliament, head! United States were influenced by it. HABEAS CORPUS ACT 1679 The writ of Habeas Corpus gives imprisonment. In 1697 the House of Habeas Corpus is a writ that exists in a person who is imprisoned the Lords passed the Habeas Corpus Act. It many countries with common law opportunity to go before a court now applies to everyone everywhere in legal systems. and challenge the lawfulness of their the United Kingdom. -

The Original Meaning of the Habeas Corpus Suspension Clause, the Right of Natural Liberty, and Executive Discretion

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal Volume 29 (2020-2021) Issue 3 The Presidency and Individual Rights Article 4 March 2021 The Original Meaning of the Habeas Corpus Suspension Clause, the Right of Natural Liberty, and Executive Discretion John Harrison Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Legal History Commons, President/Executive Department Commons, and the United States History Commons Repository Citation John Harrison, The Original Meaning of the Habeas Corpus Suspension Clause, the Right of Natural Liberty, and Executive Discretion, 29 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 649 (2021), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol29/iss3/4 Copyright c 2021 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj THE ORIGINAL MEANING OF THE HABEAS CORPUS SUSPENSION CLAUSE, THE RIGHT OF NATURAL LIBERTY, AND EXECUTIVE DISCRETION John Harrison* The Habeas Corpus Suspension Clause of Article I, Section 9, is primarily a limit on Congress’s authority to authorize detention by the executive. It is not mainly con- cerned with the remedial writ of habeas corpus, but rather with the primary right of natural liberty. Suspensions of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus are statutes that vest very broad discretion in the executive to decide which individuals to hold in custody. Detention of combatants under the law of war need not rest on a valid suspen- sion, whether the combatant is an alien or a citizen of the United States. The Suspension Clause does not affirmatively require that the federal courts have any jurisdiction to issue the writ of habeas corpus, and so does not interfere with Congress’s general control over the jurisdiction of the federal courts. -

What If the Founders Had Not Constitutionalized the Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus?

THE COUNTERFACTUAL THAT CAME TO PASS: WHAT IF THE FOUNDERS HAD NOT CONSTITUTIONALIZED THE PRIVILEGE OF THE WRIT OF HABEAS CORPUS? AMANDA L. TYLER* INTRODUCTION Unlike the other participants in this Symposium, my contribution explores a constitutional counterfactual that has actually come to pass. Or so I will argue it has. What if, this Essay asks, the Founding generation had not constitutionalized the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus? As is explored below, in many respects, the legal framework within which we are detaining suspected terrorists in this country today—particularly suspected terrorists who are citizens1—suggests that our current legal regime stands no differently than the English legal framework from which it sprang some two-hundred-plus years ago. That framework, by contrast to our own, does not enshrine the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus as a right enjoyed by reason of a binding and supreme constitution. Instead, English law views the privilege as a right that exists at the pleasure of Parliament and is, accordingly, subject to legislative override. As is also shown below, a comparative inquiry into the existing state of detention law in this country and in the United Kingdom reveals a notable contrast—namely, notwithstanding their lack of a constitutionally- based right to the privilege, British citizens detained in the United Kingdom without formal charges on suspicion of terrorist activities enjoy the benefit of far more legal protections than their counterparts in this country. The Essay proceeds as follows: Part I offers an overview of key aspects of the development of the privilege and the concept of suspension, both in England and the American Colonies, in the period leading up to ratification of the Suspension Clause as part of the United States Constitution. -

Habeas Corpus Act 1679

Status: Point in time view as at 02/04/2006. Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Habeas Corpus Act 1679. (See end of Document for details) Habeas Corpus Act 1679 1679 CHAPTER 2 31 Cha 2 An Act for the better secureing the Liberty of the Subject and for Prevention of Imprisonments beyond the Seas. X1Recital that Delays had been used by Sheriffs in making Returns of Writs of Habeas Corpus, &c. WHEREAS great Delayes have beene used by Sheriffes Goalers and other Officers to whose Custody any of the Kings Subjects have beene committed for criminall or supposed criminall Matters in makeing Returnes of Writts of Habeas Corpus to them directed by standing out an Alias and Pluries Habeas Corpus and sometimes more and by other shifts to avoid their yeilding Obedience to such Writts contrary to their Duty and the knowne Lawes of the Land whereby many of the Kings Subjects have beene and hereafter may be long detained in Prison in such Cases where by Law they are baylable to their great charge and vexation. Annotations: Editorial Information X1 Abbreviations or contractions in the original form of this Act have been expanded into modern lettering in the text set out above and below. Modifications etc. (not altering text) C1 Short title given by Short Titles Act 1896 (c. 14) [I.] Sheriff, &c. within Three Days after Service of Habeas Corpus, with the Exception of Treason and Felony, as and under the Regulations herein mentioned, to bring up the Body before the Court to which the Writ is returnable; and certify the true Causes of Imprisonment. -

Criminal Law Act 1967 (C

Criminal Law Act 1967 (c. 58) 1 SCHEDULE 4 – Repeals (Obsolete Crimes) Document Generated: 2021-04-04 Status: This version of this schedule contains provisions that are prospective. Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Criminal Law Act 1967, SCHEDULE 4. (See end of Document for details) SCHEDULES SCHEDULE 4 Section 13. REPEALS (OBSOLETE CRIMES) Modifications etc. (not altering text) C1 The text of S. 10(2), S. 13(2), Sch. 2 paras. 3, 4, 6, 10, 12(2), 13(1)(a)(c)(d), 14, Sch. 3 and Sch. 4 is in the form in which it was originally enacted: it was not reproduced in Statutes in Force and does not reflect any amendments or repeals which may have been made prior to 1.2.1991. PART I ACTS CREATING OFFENCES TO BE ABOLISHED Chapter Short Title Extent of Repeal 3 Edw. 1. The Statute of Westminster Chapter 25. the First. (Statutes of uncertain date — Statutum de Conspiratoribus. The whole Act. 20 Edw. 1). 28 Edw. 1. c. 11. (Champerty). The whole Chapter. 1 Edw. 3. Stat. 2 c. 14. (Maintenance). The whole Chapter. 1 Ric. 2. c. 4. (Maintenance) The whole Chapter. 16 Ric. 2. c. 5. The Statute of Praemunire The whole Chapter (this repeal extending to Northern Ireland). 24 Hen. 8. c. 12. The Ecclesiastical Appeals Section 2. Act 1532. Section 4, so far as unrepealed. 25 Hen. 8. c. 19. The Submission of the Clergy Section 5. Act 1533. The Appointment of Bishops Section 6. Act 1533. 25 Hen. 8. c. -

949 You Don't Know What You've

YOU DON’T KNOW WHAT YOU’VE GOT ‘TIL IT’S GONE 949 YOU DON’T KNOW WHAT YOU’VE GOT ‘TIL IT’S GONE: THE RULE OF LAW IN CANADA — PART IIh JACK WATSON* This article is the second part of an article that was Cet article constitue la deuxième partie d’un article printed in the Alberta Law Review, Volume 52, Issue paru à 689 du numéro 3, du volume 52 de la revue 3 at 689. In this part, the article explores how the rule Alberta Law Review. Dans cette partie-ci, l’auteur of law has found expression in Canada. It defines the explore de quelle manière la primauté du droit se major elements and characteristics of the rule of law. manifeste au Canada. Il détermine les principaux It then goes on to explore how the different branches éléments et principales caractéristiques de cette of government are affected and constrained by the rule primauté. L’auteur examine comment les divers of law. The role of the courts in upholding the rule of organes du gouvernement sont concernés et restreints law is emphasized, as well as the importance of par cette primauté. On y souligne le rôle des tribunaux judicial independence. pour confirmer la primauté du droit ainsi que l’importance de l’indépendance judiciaire. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. RULE OF LAW AS EXPRESSED BY CANADA ........................ 949 II. ELEMENTS OF THE RULE OF LAW IN CANADA ..................... 955 A. COMMON ELEMENTS AFFECTING GOVERNANCE ............... 956 B. ELEMENTS AFFECTING THE LEGISLATIVE BRANCH OF GOVERNMENT ............................... 969 C. ELEMENTS AFFECTING THE EXECUTIVE BRANCH OF GOVERNMENT .............................. -

Brief Amici Curiae of Legal Historians Listed Herein in Support of Respondent, I.N.S

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2001 Brief Amici Curiae of Legal Historians Listed Herein in Support of Respondent, I.N.S. v. St. Cyr, No. 00-767 (U.S. Mar. 27, 2001), . James Oldham Georgetown University Law Center Docket No. 00-767 This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/scb/63 This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/scb Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Immigration Law Commons, and the Legal History Commons United States Supreme Court Amicus Brief. IMMIGRATION AND NATURALIZATION SERVICE, Petitioner, v. Enrico ST. CYR, Respondent. No. 00-767. March 27, 2001. ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF LEGAL HISTORIANS LISTED HEREIN IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENT Timothy G. Nelson Four Times Square New York, New York 10036 (212) 735-2193 Douglas W. Baruch Michael J. Anstett Consuelo J. Hitchcock David B. Wiseman Fried, Frank, Harris, Shriver & Jacobson 1001 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Suite 800 Washington, D.C. 20004 (202) 639-7368 James Oldham Counsel of Record St. Thomas More Professor of Law & Legal History Georgetown University Law Center 600 New Jersey Avenue N.W. Washington, D.C. 20001 (202) 662-9000 Michael J. Wishnie 161 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10016 (212) 998-6430 AMICI Affiliations listed for identification purposes only. J.H. Baker Downing Professor of the Laws of England St. -

Originalism and a Forgotten Conflict Over Martial Law

Copyright 2019 by Bernadette Meyler Printed in U.S.A. Vol. 113, No. 6 ORIGINALISM AND A FORGOTTEN CONFLICT OVER MARTIAL LAW Bernadette Meyler ABSTRACT—This Symposium Essay asks what a largely forgotten conflict over habeas corpus and martial law in mid-eighteenth-century New York can tell us about originalist methods of constitutional interpretation. The episode, which involved Abraham Yates, Jr.—later a prominent Antifederalist—as well as Lord Loudoun, the commander of the British forces in America, and New York Acting Governor James De Lancey, furnishes insights into debates about martial law prior to the Founding and indicates that they may have bearing on originalist interpretations of the Suspension Clause. It also demonstrates how the British imperial context in which the American colonies were situated shaped discussions about rights in ways that originalism should address. In particular, colonists argued with colonial officials both explicitly and implicitly about the extent to which statutes as well as common law applied in the colonies. These contested statutory schemes should affect how we understand constitutional provisions: for example, they might suggest that statutes pertaining to martial law should be added to those treating habeas corpus as a backdrop against which to interpret the Suspension Clause. Furthermore, the conflict showed the significance to members of the Founding generation of the personnel applying law, whether military or civilian, rather than the substantive law applied; this emphasis could also be significant -

Criminal Law Act 1967

Status: This version of this Act contains provisions that are prospective. Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Criminal Law Act 1967. (See end of Document for details) Criminal Law Act 1967 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Annotations: Extent Information E1 Subject to s. 11(2)-(4) this Part shall not extend to Scotland or Northern Ireland see s. 11(1) 1 Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. (1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are hereby abolished. (2) Subject to the provisions of this Act, on all matters on which a distinction has previously been made between felony and misdemeanour, including mode of trial, the law and practice in relation to all offences cognisable under the law of England and Wales (including piracy) shall be the law and practice applicable at the commencement of this Act in relation to misdemeanour. [F12 Arrest without warrant. (1) The powers of summary arrest conferred by the following subsections shall apply to offences for which the sentence is fixed by law or for which a person (not previously convicted) may under or by virtue of any enactment be sentenced to imprisonment for a term of five years [F2(or might be so sentenced but for the restrictions imposed by 2 Criminal Law Act 1967 (c. -

Judiciary Rising: Constitutional Change in the United Kingdom

Copyright 2014 by Erin F. Delaney Printed in U.S.A. Vol. 108, No. 2 JUDICIARY RISING: CONSTITUTIONAL CHANGE IN THE UNITED KINGDOM Erin F. Delaney ABSTRACT—Britain is experiencing a period of dramatic change that challenges centuries-old understandings of British constitutionalism. In the past fifteen years, the British Parliament enacted a quasi-constitutional bill of rights; devolved legislative power to Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland; and created a new Supreme Court. British academics debate how each element of this transformation can be best understood: is it consistent with political constitutionalism and historic notions of parliamentary sovereignty, or does it usher in a new regime that places external, rule-of- law-based limits on Parliament? Much of this commentary examines these changes in a piecemeal fashion, failing to account for the systemic factors at play in the British system. This Article assesses the cumulative force of the many recent constitutional changes, shedding new light on the changing nature of the British constitution. Drawing on the U.S. literature on federalism and judicial power, the Article illuminates the role of human rights and devolution in the growing influence of the U.K. Supreme Court. Whether a rising judiciary will truly challenge British notions of parliamentary sovereignty is as yet unknown, but scholars and politicians should pay close attention to the groundwork being laid. AUTHOR—Assistant Professor, Northwestern University School of Law. For helpful conversations during a transatlantic visit at a very early stage of this project, I am grateful to Trevor Allan, Lord Hope, Charlie Jeffery, Lord Collins, and Stephen Tierney. -

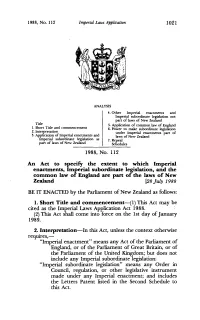

1988 No 112 Imperial Laws Application

1988, No. 112 Imperial Laws Application 1021 ANALYSIS 4. Other Imperial enactments and Imperial subordinate legislation not part of laws of New Zealand Title 5. Application of common law of England 1. Short Title and commencement 6. Power to make subordinate legislation 2. InteTretation under Imperial enactments part of 3. Application of Imperial enactments and laws of New Zealand Imperial subordinate legislation as 7. Repeal part of laws of New Zealand Scliedules 1988, No. 112 An Act to specify the extent to which Imperial enactments, Imperial subordinate legislation, and the common law of England are part of the laws of New Zealand [28 July 1988 BE IT ENACTED by the Parliament of New Zealand as follows: I. Short Tide and commencement-(1) This Act may be cited as the Imperial Laws Application Act 1988. : (2) This Act shall come into force on the 1st day of January 1989. 2. Interpretation-In this Act, unless the context otherwise requires,- "Imperial enactment" means any Act of the Parliament of England, or of the Parliament of Great Britain, or of the Parliament of the United Kingdom; but does not include any Imperial subordinate legislation: "Imperial subordinate legislation" means any Order in Council, regulation, or other legislative instrument made under any Imperial enactment; and includes the Letters Patent listed in the Second Schedule to this Act. 1022 Imperial Laws Application 1988, No. 112 8. Application of Imperial enactrnents and Imperial subordinate legislation as part of laws of New Zealand- (1) The Imperial enactments listed in the First Schedule to this Act, and the Imperial subordinate legislation listed in the Second Schedule to this Act, are hereby declared to be part of the laws of New Zealand.