National Income, 1929-1932

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edward S. Shaw* Simon Kuznets Remarked in His Capital in The

Edward S. Shaw* Simon Kuznets remarked in his Capital in rate. There is physical wealth, its ownership The American Economy, " ... extrapolation of represented by an homogeneous financial asset inflationary pressures over the next thirty in the form of common stock or "equity," and years raises a specter of intolerable conse there is wealth in the form of real money bal quences.... "1 Fifteen of the thirty years are ances. Accumulation of physical and monetary over, and inflation has accelerated. The central wealth derives from a constant rate of saving concern of this paper is whether Kuznets' pre for the community. Inflation occurs because the diction of "intolerable consequences" for capital growth rate of nominal money exceeds the markets and capital accumulation is on track or growth rate of real money demanded. patently wrong. 2 The inflation is immaculate because its pace Monetary theory distinguishes between "im is constant and perfectly foreseen and because maculate" inflation, "clean" inflation, and the inflation tax on real money balances is com "dirty" inflation. It is the last of these that pensated precisely by a deposit-rate of interest Kuznets dreaded and that we have endured. The on money. It is fully anticipated, and it does not first section below deals very briefly with dif impose a relative penalty on the money form of ferences between the three styles of inflation. wealth. Money-wage rates rise faster than out The second section is a catalogue of ways in put prices in the degree that labor productivity which dirty inflation may obstruct and distort is growing. -

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

Nazi Privatization in 1930S Germany1 by GERMÀ BEL

Economic History Review (2009) Against the mainstream: Nazi privatization in 1930s Germany1 By GERMÀ BEL Nationalization was particularly important in the early 1930s in Germany.The state took over a large industrial concern, large commercial banks, and other minor firms. In the mid-1930s, the Nazi regime transferred public ownership to the private sector. In doing so, they went against the mainstream trends in western capitalistic countries, none of which systematically reprivatized firms during the 1930s. Privatization was used as a political tool to enhance support for the government and for the Nazi Party. In addition, growing financial restrictions because of the cost of the rearmament programme provided additional motivations for privatization. rivatization of large parts of the public sector was one of the defining policies Pof the last quarter of the twentieth century. Most scholars have understood privatization as the transfer of government-owned firms and assets to the private sector,2 as well as the delegation to the private sector of the delivery of services previously delivered by the public sector.3 Other scholars have adopted a much broader meaning of privatization, including (besides transfer of public assets and delegation of public services) deregulation, as well as the private funding of services previously delivered without charging the users.4 In any case, modern privatization has been usually accompanied by the removal of state direction and a reliance on the free market. Thus, privatization and market liberalization have usually gone together. Privatizations in Chile and the UK, which began to be implemented in the 1970s and 1980s, are usually considered the first privatization policies in modern history.5 A few researchers have found earlier instances. -

Presentation Slides

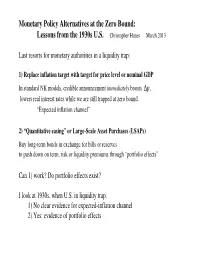

Monetary Policy Alternatives at the Zero Bound: Lessons from the 1930s U.S. Christopher Hanes March 2013 Last resorts for monetary authorities in a liquidity trap: 1) Replace inflation target with target for price level or nominal GDP In standard NK models, credible announcement immediately boosts ∆p, lowers real interest rates while we are still trapped at zero bound. “Expected inflation channel” 2) “Quantitative easing” or Large-Scale Asset Purchases (LSAPs) Buy long-term bonds in exchange for bills or reserves to push down on term, risk or liquidity premiums through “portfolio effects” Can 1) work? Do portfolio effects exist? I look at 1930s, when U.S. in liquidity trap. 1) No clear evidence for expected-inflation channel 2) Yes: evidence of portfolio effects Expected-inflation channel: theory Lessons from the 1930s U.S. β New-Keynesian Phillips curve: ∆p ' E ∆p % (y&y n) t t t%1 γ t T β a distant horizon T ∆p ' E [∆p % (y&y n) ] t t t%T λ j t%τ τ'0 n To hit price-level or $AD target, authorities must boost future (y&y )t%τ For any given path of y in near future, while we are still in liquidity trap, that raises current ∆pt , reduces rt , raises yt , lifts us out of trap Why it might fail: - expectations not so forward-looking, rational - promise not credible Svensson’s “Foolproof Way” out of liquidity trap: peg to depreciated exchange rate “a conspicuous commitment to a higher price level in the future” Expected-inflation channel: 1930s experience Lessons from the 1930s U.S. -

Hitler's American Model

Hitler’s American Model The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law James Q. Whitman Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford 1 Introduction This jurisprudence would suit us perfectly, with a single exception. Over there they have in mind, practically speaking, only coloreds and half-coloreds, which includes mestizos and mulattoes; but the Jews, who are also of interest to us, are not reckoned among the coloreds. —Roland Freisler, June 5, 1934 On June 5, 1934, about a year and a half after Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of the Reich, the leading lawyers of Nazi Germany gathered at a meeting to plan what would become the Nuremberg Laws, the notorious anti-Jewish legislation of the Nazi race regime. The meeting was chaired by Franz Gürtner, the Reich Minister of Justice, and attended by officials who in the coming years would play central roles in the persecution of Germany’s Jews. Among those present was Bernhard Lösener, one of the principal draftsmen of the Nuremberg Laws; and the terrifying Roland Freisler, later President of the Nazi People’s Court and a man whose name has endured as a byword for twentieth-century judicial savagery. The meeting was an important one, and a stenographer was present to record a verbatim transcript, to be preserved by the ever-diligent Nazi bureaucracy as a record of a crucial moment in the creation of the new race regime. That transcript reveals the startling fact that is my point of departure in this study: the meeting involved detailed and lengthy discussions of the law of the United States. -

Trends in Factor Shares: Facts and Implications

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Karabarbounis, Loukas; Neiman, Brent Article Trends in factor shares: Facts and implications NBER Reporter Provided in Cooperation with: National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), Cambridge, Mass. Suggested Citation: Karabarbounis, Loukas; Neiman, Brent (2017) : Trends in factor shares: Facts and implications, NBER Reporter, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), Cambridge, MA, Iss. 4, pp. 19-22 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/178760 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu systematically benefit firstborns and help 2 S. Black, P. Devereux, and K. Adolescent Behavior,” Economic Inquiry, Trends in Factor Shares: Facts and Implications explain their generally better outcomes. -

Econometrics As a Pluralistic Scientific Tool for Economic Planning: on Lawrence R

Econometrics as a Pluralistic Scientific Tool for Economic Planning: On Lawrence R. Klein’s Econometrics Erich Pinzón-Fuchs To cite this version: Erich Pinzón-Fuchs. Econometrics as a Pluralistic Scientific Tool for Economic Planning: On Lawrence R. Klein’s Econometrics. 2016. halshs-01364809 HAL Id: halshs-01364809 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01364809 Preprint submitted on 12 Sep 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Documents de Travail du Centre d’Economie de la Sorbonne Econometrics as a Pluralistic Scientific Tool for Economic Planning: On Lawrence R. Klein’s Econometrics Erich PINZÓN FUCHS 2014.80 Maison des Sciences Économiques, 106-112 boulevard de L'Hôpital, 75647 Paris Cedex 13 http://centredeconomiesorbonne.univ-paris1.fr/ ISSN : 1955-611X Econometrics as a Pluralistic Scientific Tool for Economic Planning: On Lawrence R. Klein’s Econometrics Erich Pinzón Fuchs† October 2014 Abstract Lawrence R. Klein (1920-2013) played a major role in the construction and in the further dissemination of econometrics from the 1940s. Considered as one of the main developers and practitioners of macroeconometrics, Klein’s influence is reflected in his application of econometric modelling “to the analysis of economic fluctuations and economic policies” for which he was awarded the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel in 1980. -

Revision Booklet – Germany

GERMANY IN TRANSITION, 1919-1939 There are seven key issues to learn: 1. What challenges were faced by the Weimar Republic from 1919-1923? 2. Why were the Stresemann years considered a ‘golden age’? 3. How and why did the Weimar Republic collapse between 1929 and 1933? 4. How did the Nazis consolidate their power between 1933 and 1934? 5. How did Nazi economic, social and racial policy affect life in Germany? 6. What methods did the Nazis use to control Germany? 7. What factors led to the outbreak of war in 1939? 1. What challenges were faced by the Weimar Republic from 1919 to 1923? ★ The Weimar Republic was Germany’s new democratic government after WW1. Faced many problems in the first few years of power. ★ Following Germany’s surrender, many people were unhappy and disillusioned. ★ The terms of the Versailles Treaty were very harsh. Germans felt betrayed, bitter and desperate for revenge. ★ Weimar faced challenges to its power: Spartacist Uprising, Kapp Putsch, Munich Putsch, the Ruhr Crisis ★ Hyperinflation Key words Weimar Republic Democracy Coalition Treaty Reparations KPD Spartacists Communists Putsch Kapp Ruhr Passive resistance Hyperinflation 2. Weimar recovers! Was the period 1924 to 1929 a ‘golden age’? ★ The economy recovered: Dawes Plan; a new currency called the Rentenmark; the Young Plan; too dependent on US loans? ★ A number of successes abroad: the Locarno Pact; the League of Nations; the Kellogg- Briand Pact; the role of Stesemann. ★ Political developments: support for the moderate parties; lack of support for the extremist parties. ★ Social developments: improved standard of living (housing, wages, unemployment insurance); the status of women improved; cultural changes Key words Dawes Plan Recovery Locarno League of Nations Kellogg-Briand Stresemann 3. -

Link to Nazi Control KO

Eight Steps to Becoming Dictator (Rigged German Election Leads To Psychopath Nazi Nazi Control Assessment 3 Fuhrer) 1 Reichstag Fire - 27 Feb 1933 If you are asked about how Hitler The Reichstag (the German Parliament) burned down. Hitler used it as an consolidated his power, remember that the question is not just about excuse to arrest many of his Communist opponents, and as a major platform describing what happened and what R in his election campaign of March 1933. The fire was so convenient that Hitler did. You should many people at the time claimed that the Nazis had burned it down, and then explain how Hitler's actions helped him just blamed the Communists. to consolidate his power - it is more 2 General Election - 5 March 1933 about the effects of what he did. The Hitler held a general election, appealing to the German people to give him a table below describes how certain events that happened between 1933 and G clear mandate. Only 44% of the people voted Nazi, which did not give him a 1934 gave Hitler the opportunity to majority in the Reichstag, so Hitler arrested the 81 Communist deputies consolidate power. (which did give him a majority). Goering become Speaker of the Reichstag. 3 Enabling Act - 23 March 1933 The Reichstag voted to give Hitler the power to make his own laws. Nazi stormtroopers stopped opposition deputies going in, and beat up anyone who E dared to speak against it. The Enabling Act made Hitler the dictator of The Police State Germany, with power to do anything he liked - legally. -

Droughts of 1930-34

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Harold L. Ickes, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. C. Mendenhall, Director Water-Supply Paper 680 DROUGHTS OF 1930-34 BY JOHN C. UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1936 i'For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. Price 20 cents CONTENTS Page Introduction ________ _________-_--_____-_-__---___-__________ 1 Droughts of 1930 and 1931_____._______________________ 5 Causes_____________________________________________________ 6 Precipitation. ____________________________________________ 6 Temperature ____________-_----_--_-_---___-_-_-_-_---_-_- 11 Wind.._.. _ 11 Effect on ground and surface water____________________________ 11 General effect___________________________________________ 11 Ground water___________________________ _ _____________ _ 22 Surface water___________________________________________ 26 Damage___ _-___---_-_------------__---------___-----_----_ 32 Vegetation.____________________________________________ 32 Domestic and industrial water supplies_____________________ 36 Health____-_--___________--_-_---_-----_-----_-_-_--_.__- 37 Power.______________________________________________ 38 Navigation._-_-----_-_____-_-_-_-_--__--_------_____--___ 39 Recreation and wild life--___--_---__--_-------------_--_-__ 41 Relief - ---- . 41 Drought of 1934__ 46 Causes_ _ ___________________________________________________ 46 Precipitation.____________________________________________ 47 Temperature._____________---_-___----_________-_________ 50 Wind_____________________________________________ -

ΒΙΒΛΙΟΓ ΡΑΦΙΑ Bibliography

Τεύχος 53, Οκτώβριος-Δεκέμβριος 2019 | Issue 53, October-December 2019 ΒΙΒΛΙΟΓ ΡΑΦΙΑ Bibliography Βραβείο Νόμπελ στην Οικονομική Επιστήμη Nobel Prize in Economics Τα τεύχη δημοσιεύονται στον ιστοχώρο της All issues are published online at the Bank’s website Τράπεζας: address: https://www.bankofgreece.gr/trapeza/kepoe https://www.bankofgreece.gr/en/the- t/h-vivliothhkh-ths-tte/e-ekdoseis-kai- bank/culture/library/e-publications-and- anakoinwseis announcements Τράπεζα της Ελλάδος. Κέντρο Πολιτισμού, Bank of Greece. Centre for Culture, Research and Έρευνας και Τεκμηρίωσης, Τμήμα Documentation, Library Section Βιβλιοθήκης Ελ. Βενιζέλου 21, 102 50 Αθήνα, 21 El. Venizelos Ave., 102 50 Athens, [email protected] Τηλ. 210-3202446, [email protected], Tel. +30-210-3202446, 3202396, 3203129 3202396, 3203129 Βιβλιογραφία, τεύχος 53, Οκτ.-Δεκ. 2019, Bibliography, issue 53, Oct.-Dec. 2019, Nobel Prize Βραβείο Νόμπελ στην Οικονομική Επιστήμη in Economics Συντελεστές: Α. Ναδάλη, Ε. Σεμερτζάκη, Γ. Contributors: A. Nadali, E. Semertzaki, G. Tsouri Τσούρη Βιβλιογραφία, αρ.53 (Οκτ.-Δεκ. 2019), Βραβείο Nobel στην Οικονομική Επιστήμη 1 Bibliography, no. 53, (Oct.-Dec. 2019), Nobel Prize in Economics Πίνακας περιεχομένων Εισαγωγή / Introduction 6 2019: Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer 7 Μονογραφίες / Monographs ................................................................................................... 7 Δοκίμια Εργασίας / Working papers ...................................................................................... -

![Simon Kuznets [Ideological Profiles of the Economics Laureates] Daniel B](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5929/simon-kuznets-ideological-profiles-of-the-economics-laureates-daniel-b-1175929.webp)

Simon Kuznets [Ideological Profiles of the Economics Laureates] Daniel B

Simon Kuznets [Ideological Profiles of the Economics Laureates] Daniel B. Klein, Ryan Daza, and Hannah Mead Econ Journal Watch 10(3), September 2013: 411-413 Abstract Simon Kuznets is among the 71 individuals who were awarded the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel between 1969 and 2012. This ideological profile is part of the project called “The Ideological Migration of the Economics Laureates,” which fills the September 2013 issue of Econ Journal Watch. Keywords Classical liberalism, economists, Nobel Prize in economics, ideology, ideological migration, intellectual biography. JEL classification A11, A13, B2, B3 Link to this document http://econjwatch.org/file_download/738/KuznetsIPEL.pdf IDEOLOGICAL PROFILES OF THE ECONOMICS LAUREATES Simon Kuznets by Daniel B. Klein, Ryan Daza, and Hannah Mead Simon Kuznets (1901–1985) was born in Russia. In 1922, Kuznets emigrated with his family to the United States. He earned his Ph.D. from Columbia University in 1926 and started working at the National Bureau of Economic Research the following year. Between 1930 and 1971, Kuznets taught at the University of Pennsylvania, Johns Hopkins University, and then Harvard University (Kuznets 1992a/1971). His ideological views do not seem to have changed significantly during his adult life. Kuznets won the Nobel Prize in Economic Science for “for his empirically founded interpretation of economic growth which has led to new and deepened insight into the economic and social structure and process of development.” In a speech at the award ceremony, Bertil Ohlin praised Kuznets for having “consistently addressed himself to giving quantitative precision to economic magnitudes which seem [to] be relevant to an understanding of processes of social change.