AQA Aos4: Music for Theatre – Part Two

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996 Stage by Stage The Development of the National Theatre from 1848 Designed by Michael Mayhew Compiled by Lyn Haill & Stephen Wood With thanks to Richard Mangan and The Mander & Mitchenson Theatre Collection, Monica Sollash and The Theatre Museum The majority of the photographs in the exhibition were commissioned by the National Theatre and are part of its archive The exhibition was funded by The Royal National Theatre Foundation Richard Eyre. Photograph by John Haynes. 1988 To mark the company’s 25th birthday in Peter Hall’s last year as Director of the National October, The Queen approves the title ‘Royal’ Theatre. He stages three late Shakespeare for the National Theatre, and attends an plays (The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, and anniversary gala in the Olivier. Cymbeline) in the Cottesloe then in the Olivier, and leaves to start his own company in the The funds raised are to set up a National West End. Theatre Endowment Fund. Lord Rayne retires as Chairman of the Board and is succeeded ‘This building in solid concrete will be here by the Lady Soames, daughter of Winston for ever and ever, whatever successive Churchill. governments can do to muck it up. The place exists as a necessary part of the cultural scene Prince Charles, in a TV documentary on of this country.’ Peter Hall architecture, describes the National as ‘a way of building a nuclear power station in the September: Richard Eyre takes over as Director middle of London without anyone objecting’. of the National. 1989 Alan Bennett’s Single Spies, consisting of two A series of co-productions with regional short plays, contains the first representation on companies begins with Tony Harrison’s version the British stage of a living monarch, in a scene of Molière’s The Misanthrope, presented with in which Sir Anthony Blunt has a discussion Bristol Old Vic and directed by its artistic with ‘HMQ’. -

February 7, 2021

VILLANOVA THEATRE PRESENTS STREAMING JANUARY 28 - FEBRUARY 7, 2021 About Villanova University Since 1842, Villanova University’s Augustinian Catholic intellectual tradition has been the cornerstone of an academic community in which students learn to think critically, act compassionately and succeed while serving others. There are more than 10,000 undergraduate, graduate and law students in the University’s six colleges – the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, the Villanova School of Business, the College of Engineering, the M. Louise Fitzpatrick College of Nursing, the College of Professional Studies and the Villanova University School of Law. As students grow intellectually, Villanova prepares them to become ethical leaders who create positive change everywhere life takes them. In Gratitude The faculty, staff and students of Villanova Theatre extend sincere gratitude to those generous benefactors who have established endowed funds in support of our efforts: Marianne M. and Charles P. Connolly Jr. ’70 Dorothy Ann and Bernard A. Coyne, Ph.D. ̓55 Patricia M. ’78 and Joseph C. Franzetti ’78 The Donald R. Kurz Family Peter J. Lavezzoli ’60 Patricia A. Maskinas Msgr. Joseph F. X. McCahon ’65 Mary Anne C. Morgan ̓70 and Family & Friends of Brian G. Morgan ̓67, ̓70 Anthony T. Ponturo ’74 Eric J. Schaeffer and Susan Trimble Schaeffer ’78 The Thomas and Tracey Gravina Foundation For information about how you can support the Theatre Department, please contact Heather Potts-Brown, Director of Annual Giving, at (610) 519-4583. gratefully acknowledges the generous support of our many patrons & subscribers. We wish to offer special thanks to our donors. 20-21 Benefactors A Running Friend William R. -

Abby Wiggins, Soprano Junior Recital

THE BELHAVEN COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC Dr. Stephen W. Sachs, Chair presents Abby Wiggins, soprano Junior Recital assisted by Hannah Thomas, accompanist John Mathieu, bass & Eleana Davis, soprano Saturday, March 27, 2010 2:00 p.m. Belhaven University Center for the Arts Concert Hall BELHAVEN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC MISSION STATEMENT The Music Department seeks to produce transformational leaders in the musical arts who will have profound influence in homes, churches, private studios, educational institutions, and on the concert stage. While developing the God-bestowed musical talents of music majors, minors, and elective students, we seek to provide an integrative understanding of the musical arts from a Christian world and life view in order to equip students to influence the world of ideas. The music major degree program is designed to prepare students for graduate study while equipping them for vocational roles in performance, church music, and education. The Belhaven University Music Department exists to multiply Christian leaders who demonstrate unquestionable excellence in the musical arts and apply timeless truths in every aspect of their artistic discipline. The Music Department of Belhaven University directs you to “Arts Ablaze 2009-2010.” Read about many of the excellent performances and presentations scheduled throughout this academic year at Belhaven University by the Arts Division. Please take a complimentary copy of “Arts Ablaze 2009-2010” with you. The Music Department would like to thank our many community partners for their support of Christian Arts Education at Belhaven University through their advertising in “Arts Ablaze 2009-2010”. It is through these and other wonderful relationships in the greater Jackson community that makes an afternoon like this possible at Belhaven. -

“Kiss Today Goodbye, and Point Me Toward Tomorrow”

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Missouri: MOspace “KISS TODAY GOODBYE, AND POINT ME TOWARD TOMORROW”: REVIVING THE TIME-BOUND MUSICAL, 1968-1975 A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School At the University of Missouri In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By BRYAN M. VANDEVENDER Dr. Cheryl Black, Dissertation Supervisor July 2014 © Copyright by Bryan M. Vandevender 2014 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled “KISS TODAY GOODBYE, AND POINT ME TOWARD TOMORROW”: REVIVING THE TIME-BOUND MUSICAL, 1968-1975 Presented by Bryan M. Vandevender A candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Dr. Cheryl Black Dr. David Crespy Dr. Suzanne Burgoyne Dr. Judith Sebesta ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I incurred several debts while working to complete my doctoral program and this dissertation. I would like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to several individuals who helped me along the way. In addition to serving as my dissertation advisor, Dr. Cheryl Black has been a selfless mentor to me for five years. I am deeply grateful to have been her student and collaborator. Dr. Judith Sebesta nurtured my interest in musical theatre scholarship in the early days of my doctoral program and continued to encourage my work from far away Texas. Her graduate course in American Musical Theatre History sparked the idea for this project, and our many conversations over the past six years helped it to take shape. -

The Tony-Award-Winning Creators of Les Misérables and Miss Saigon

Report on the January-February 2017 University of Virginia Events around Les Misérables Organized by Professor Emeritus Marva Barnett Thanks to the generous grant from the Arts Endowment, supported by the Provost’s Office Course Enhancement Grant connected to my University Seminar, Les Misérables Today, the University of Virginia hosted several unique events, including the world’s first exhibit devoted to caricatures and cartoons about Victor Hugo’s epic novel and the second UVA artistic residency with the award-winning creators of the world’s longest-running musical—artists who have participated in no other artistic residencies. These events will live on through the internet, including the online presence of the Les Misérables Just for Laughs scholarly catalogue and the video of the February 23 conversation with Boublil and Schönberg. Les Misérables Just for Laughs / Les Misérables Pour Rire Exhibit in the Rotunda Upper West Oval Room, Jan. 21-Feb. 28 Before it was made into over fifty films and an award-winning musical, Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables was a rampant best seller when it appeared in 1862. The popular cartoonists who had caricatured Hugo for thirty years leapt at the chance to satirize his epic novel. With my assistance and that of Emily Umansky (CLAS/Batten ’17), French Hugo specialist Gérard Pouchain mounted the first-ever exhibit of original publications of Les Misérables caricatures— ranging from parodies to comic sketches of the author with his characters. On January 23, at 4:00 p.m. he gave his illustrated French presentation, “La caricature au service de la gloire, ou Victor Hugo raconté par le portrait-charge,” in the Rotunda Dome Room to approximately 25 UVA faculty and students, as well as Charlottesville community members associated with the Alliance Française. -

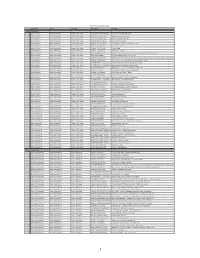

South West Regional Event List

South West Regional Festival Event Section Room Event Type School Name Event Title Senior Virtual Solo E Senior SW Solo A Senior Virtual Solo E Musical - Solo Musical HILLSBOROUGH HIGH SCHOOL Here I Am - Dirty Rotten Scoundrels Senior SW Solo A Senior Virtual Solo E Musical - Solo Musical Academy of the Holy Names What Only Love Can See-Caplin Senior SW Solo A Senior Virtual Solo E Musical - Solo Musical Academy of the Holy Names Watch What Happens-Newsies Senior SW Solo A Senior Virtual Solo E Musical - Solo Musical Academy of the Holy Names Dear Friend-She Loves Me Senior SW Solo A Senior Virtual Solo E Musical - Solo Musical Academy of the Holy Names The Writing on the Wall-Mystery of Edwin Drood Senior SW Solo A Senior Virtual Solo E Musical - Solo Musical Academy of the Holy Names Nothing-A Chorus Line Senior SW Solo A Senior Virtual Solo E Musical - Solo Musical SUNLAKE HIGH SCHOOL In Short- Edges Senior SW Solo A Senior Virtual Solo E Musical - Solo Musical SUNLAKE HIGH SCHOOL Screw Loose- Cry Baby Senior SW Solo A Senior Virtual Solo E Musical - Solo Musical NEWSOME HIGH SCHOOL 096623 The Beauty Is from The Light in the Piazza by Adam Guettel and Craig Lucas Senior SW Solo A Senior Virtual Solo E Musical - Solo Musical DAYSPRING ACADEMY Someone To Watch Over Me - Crazy For You Senior SW Solo A Senior Virtual Solo E Musical - Solo Musical NEWSOME HIGH SCHOOL 096623 Getting There from In Transit by Kristen Anderson-Lopez, James-Allen Ford, Russ Kaplan and Sara Wordsworth Senior SW Solo A Senior Virtual Solo E Musical - Solo Musical SUNLAKE HIGH SCHOOL Orphan at 33- Twisted- THE UNTOLD STORY OF A ROYAL VIZIER Senior SW Solo A Senior Virtual Solo E Musical - Solo Musical ST. -

King and Country: Shakespeare’S Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company

2016 BAM Winter/Spring #KingandCountry Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, and Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board The Ohio State University present Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company BAM Harvey Theater Mar 24—May 1 Season Sponsor: Directed by Gregory Doran Set design by Stephen Brimson Lewis Global Tour Premier Partner Lighting design by Tim Mitchell Music by Paul Englishby Leadership support for King and Country Sound design by Martin Slavin provided by the Jerome L. Greene Foundation. Movement by Michael Ashcroft Fights by Terry King Major support for Henry V provided by Mark Pigott KBE. Major support provided by Alan Jones & Ashley Garrett; Frederick Iseman; Katheryn C. Patterson & Thomas L. Kempner Jr.; and Jewish Communal Fund. Additional support provided by Mercedes T. Bass; and Robert & Teresa Lindsay. #KingandCountry Royal Shakespeare Company King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings BAM Harvey Theater RICHARD II—Mar 24, Apr 1, 5, 8, 12, 14, 19, 26 & 29 at 7:30pm; Apr 17 at 3pm HENRY IV PART I—Mar 26, Apr 6, 15 & 20 at 7:30pm; Apr 2, 9, 23, 27 & 30 at 2pm HENRY IV PART II—Mar 28, Apr 2, 7, 9, 21, 23, 27 & 30 at 7:30pm; Apr 16 at 2pm HENRY V—Mar 31, Apr 13, 16, 22 & 28 at 7:30pm; Apr 3, 10, 24 & May 1 at 3pm ADDITIONAL CREATIVE TEAM Company Voice -

Colonial Concert Series Featuring Broadway Favorites

Amy Moorby Press Manager (413) 448-8084 x15 [email protected] Becky Brighenti Director of Marketing & Public Relations (413) 448-8084 x11 [email protected] For Immediate Release, Please: Berkshire Theatre Group Presents Colonial Concert Series: Featuring Broadway Favorites Kelli O’Hara In-Person in the Berkshires Tony Award-Winner for The King and I Norm Lewis: In Concert Tony Award Nominee for The Gershwins’ Porgy & Bess Carolee Carmello: My Outside Voice Three-Time Tony Award Nominee for Scandalous, Lestat, Parade Krysta Rodriguez: In Concert Broadway Actor and Star of Netflix’s Halston Stephanie J. Block: Returning Home Tony Award-Winner for The Cher Show Kate Baldwin & Graham Rowat: Dressed Up Again Two-Time Tony Award Nominee for Finian’s Rainbow, Hello, Dolly! & Broadway and Television Actor An Evening With Rachel Bay Jones Tony, Grammy and Emmy Award-Winner for Dear Evan Hansen Click Here To Download Press Photos Pittsfield, MA - The Colonial Concert Series: Featuring Broadway Favorites will captivate audiences throughout the summer with evenings of unforgettable performances by a blockbuster lineup of Broadway talent. Concerts by Tony Award-winner Kelli O’Hara; Tony Award nominee Norm Lewis; three-time Tony Award nominee Carolee Carmello; stage and screen actor Krysta Rodriguez; Tony Award-winner Stephanie J. Block; two-time Tony Award nominee Kate Baldwin and Broadway and television actor Graham Rowat; and Tony Award-winner Rachel Bay Jones will be presented under The Big Tent outside at The Colonial Theatre in Pittsfield, MA. Kate Maguire says, “These intimate evenings of song will be enchanting under the Big Tent at the Colonial in Pittsfield. -

PARADE Study Guide Written by Talia Rockland Edited by Yuko Kurahashi

Study Guide, Parade PARADE Study Guide Written by Talia Rockland Edited by Yuko Kurahashi TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT THE PLAY ................................................................. 2 GLOSSARY ............................................................................. 3 CONTEXT ............................................................................... 6 MARY PHAGAN MURDER AND LEO FRANK TRIAL TIMELINE ............................................................................... 9 HISOTRICAL INFLUENCES ON THE EVENTS OF PARADE11 TRIAL OUTCOMES .............................................................. 11 SOURCES .............................................................................. 12 1 Study Guide, Parade ABOUT THE PLAY Parade was written by Alfred Uhry and lyrically and musically composed by Jason Robert Brown in 1998. The show opened at the Lincoln Center Theatre on December 17th, 1998 and closed February 28th, 1999 with a total of 39 previews and 85 performances. It won the Tony Award for Best Book of a Musical and Best Original Score and the New York Drama Critics Circle for Best Musical. It also won Drama Desk awards for Outstanding Musical, Outstanding Actor (Brent Carver), Outstanding Actress (Carolee Carmelo), Outstanding Book of a Musical, Outstanding Orchestrations (Don Sebesky), and Outstanding Score of a Musical. Alfred Uhry is a playwright, lyricist and screenwriter. Born in Atlanta, Georgia from German- Jewish descendants, Uhry graduated Brown University in 1958 with a degree in English and Drama. Uhry relocated to New York City where he taught English and wrote plays. His first success was the musical adaption of The Robber Bridegroom. He received a Tony Award nomination for Best Book of a Musical. His other successful works include Driving Miss Daisy, Last Night of Ballyhoo, and LoveMusik. Jason Robert Brown is a composer, lyricist, conductor, arranger, orchestrator, director and performer. He was born in Ossining, New York and was raised Jewish. He attended the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York. -

The Enduring Power of Musical Theatre Curated by Thom Allison

THE ENDURING POWER OF MUSICAL THEATRE CURATED BY THOM ALLISON PRODUCTION SUPPORT IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY NONA MACDONALD HEASLIP PRODUCTION CO-SPONSOR LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Welcome to the Stratford Festival. It is a great privilege to gather and share stories on this beautiful territory, which has been the site of human activity — and therefore storytelling — for many thousands of years. We wish to honour the ancestral guardians of this land and its waterways: the Anishinaabe, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the Wendat, and the Attiwonderonk. Today many Indigenous peoples continue to call this land home and act as its stewards, and this responsibility extends to all peoples, to share and care for this land for generations to come. CURATED AND DIRECTED BY THOM ALLISON THE SINGERS ALANA HIBBERT GABRIELLE JONES EVANGELIA KAMBITES MARK UHRE THE BAND CONDUCTOR, KEYBOARD ACOUSTIC BASS, ELECTRIC BASS, LAURA BURTON ORCHESTRA SUPERVISOR MICHAEL McCLENNAN CELLO, ACOUSTIC GUITAR, ELECTRIC GUITAR DRUM KIT GEORGE MEANWELL DAVID CAMPION The videotaping or other video or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited. A MESSAGE FROM OUR ARTISTIC DIRECTOR WORLDS WITHOUT WALLS Two young people are in love. They’re next- cocoon, and now it’s time to emerge in a door neighbours, but their families don’t get blaze of new colour, with lively, searching on. So they’re not allowed to meet: all they work that deals with profound questions and can do is whisper sweet nothings to each prompts us to think and see in new ways. other through a small gap in the garden wall between them. Eventually, they plan to While I do intend to program in future run off together – but on the night of their seasons all the plays we’d planned to elopement, a terrible accident of fate impels present in 2020, I also know we can’t just them both to take their own lives. -

Lesher Will Hear the People Sing Contra Costa Musical Theatre Closes 53Rd Season with Epic Production

Lesher Will Hear The People Sing Contra Costa Musical Theatre Closes 53rd Season with Epic Production WALNUT CREEK, February 15, 2014 — Contra Costa Musical Theatre (CCMT) will present the epic musical “Les Miserables“at Walnut Creek’s Lesher Center for the Arts, March 21 through April 20, 2014. Tickets for “Les Miserables” range from $45 to $54 (with discounts available for seniors, youth, and groups) and are on sale now at the Lesher Center for the Arts Ticket Office, 1601 Civic Drive in Walnut Creek, 925.943.SHOW (943-7469). Tickets can also be purchased online at www.lesherArtscenter.org. Based on the novel of the same name by Victor Hugo, “Les Miserables” has music by Claude-Michel Schonberg, lyrics by Alain Boublil, Jean-Marc Natel and Herbert Kretzmer and book by Schonberg, Boublil, Trevor Nunn and John Caird. The show premiered in London, where it has been running continuously since 1985, making it the longest-running musical ever in the West End. It opened on Broadway in 1987 and ran for 6,680 performances, closing in 2003, making it the fifth longest-running show on Broadway. A Broadway revival ran from 2008 through 2010. A film version of the musical opened in 2012 and was nominated for eight Academy Awards, winning three statues. “Les Miserables” won eight Tony Awards including Best Musical. Set in early 19th-century France, it follows the story of Jean Valjean, a French peasant, and his quest for redemption after serving nineteen years in jail for having stolen a loaf of bread for his sister’s starving child. -

YCH Monograph TOTAL 140527 Ts

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Transformation of The Musical: The Hybridization of Tradition and Contemporary Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1hr7f5x4 Author Hu, Yuchun Chloé Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Transformation of The Musical: The Hybridization of Tradition and Contemporary A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirement for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Yu-Chun Hu 2014 Copyright by Yu-Chun Hu 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Transformation of The Musical: The Hybridization of Tradition and Contemporary by Yu-Chun Hu Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Ian Krouse, Chair Music and vision are undoubtedly connected to each other despite opera and film. In opera, music is the primary element, supported by the set and costumes. The set and costumes provide a visual interpretation of the music. In film, music and sound play a supporting role. Music and sound create an ambiance in films that aid in telling the story. I consider the musical to be an equal and reciprocal balance of music and vision. More importantly, a successful musical is defined by its plot, music, and visual elements, and how well they are integrated. Observing the transformation of the musical and analyzing many different genres of concert music, I realize that each new concept of transformation always blends traditional and contemporary elements, no matter how advanced the concept is or was at the time. Through my analysis of three musicals, I shed more light on where this ii transformation may be heading and what tradition may be replaced by a new concept, and vice versa.