Flat Foot in a Random Population and Its Impact on Quality of Life and Functionality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015/03/28. Publicación: La Voz De Galicia. Edición

L2 | BARBANZA-MUROS-NOIA | Sábado, 28 de marzo del 2015 | La Voz de Galicia González Laxe ofreció una clase de economía aplicada en Noia El expresidente de la Xunta de Galicia clausuró el programa de Climántica que involucró a alumnos barbanzanos y canarios RAQUEL IGLESIAS meno migratorio y el aislamien- la alumna Paula Insua ofreció la RIBEIRA / LA VOZ to de la península. Su interven- charla A auga no Planeta, en Ga- ción despertó gran interés entre licia e en Canarias. Esta estudian- Los alumnos canarios que par- los estudiantes, lo que obligó a te fue seleccionada como delega- ticiparon en los últimos días en prolongar el tiempo previsto para da, junto a otros seis, de la euro- un intercambio en Barbanza no un coloquio. Los jóvenes no du- rregión educativa Galicia-norte podían haberse llevado una vi- daron en preguntar a González de Portugal que participará en la sión más completa de esta tierra. Laxe por qué es necesario llevar conferencia juvenil europea Imos Fernando González Laxe clausu- a cabo prospecciones petrolífi- coidar do Planeta que se celebra- ró el programa de Climántica en cas en Canarias si cuentan con el rá en Bruselas en mayo. el que se involucraron tres insti- viento como aliado de las ener- Simposio de medio ambiente tutos de la zona y otro de las is- gías renovables. las para luchar contra el cambio Cabe destacar que al acto asis- A continuación se llevó a cabo climático. El expresidente de la tieron el alcalde de Noia, Rafael un simposio sobre el medio am- Xunta impartió una conferencia García Guerrero, y el de Boiro, biente de Canarias en el que se en el coliseo Noela en la que ofre- Juan José Dieste, ya que los alum- presentaron aspectos relativos ció una visión de Galicia desde nos barbanzanos que participa- al vulcanismo, a la historia de la economía aplicada. -

Analysis of the Desegregation and Social Inclusion Policies in The

Análisis de las políticas de desegregación e inclusión social en el contexto español Carmen Gago-Cortés Universidade da Coruña / Departamento de Empresa, Facultad de Economía y Empresa A Coruña / España Isabel Novo-Corti Universidade da Coruña / Departamento de Economía, Facultad de Economía y Empresa A Coruña / España En España, muchas actuaciones de erradicación del chabolismo se centraban únicamente en la eliminación de los aspectos más visibles del problema, generando desacuerdo social. Este trabajo analiza en qué medida las nuevas políticas de realojo y dispersión aplicadas recientemente en los poblados chabolistas del noroeste de este país fomentan actitudes favorables hacia la inclusión social de las personas desplazadas, la mayoría de etnia gitana. Para ello se ha realizado un cuestionario que recoge las percepciones tanto de los afectados por los realojos como de las personas que los acogen en sus vecindarios. Mediante el análisis cuantitativo y exploratorio de los datos, se ha detectado una buena predisposición social hacia la inclusión social de las personas chabolistas en las viviendas normalizadas, identificando aquellos aspectos en los que es necesario reforzar este tipo de intervenciones. Palabras clave: poblados chabolistas; segregación; inclusión; actitudes; gitanos. Análise das políticas de desagregação e inclusão social no contexto espanhol Na Espanha, muitas ações de erradicação de favelas foram focadas apenas na eliminação dos aspectos mais visíveis do problema, criando discórdia social. Este artigo analisa em que medida as novas políticas de reassentamento e dispersão recentemente implementadas nas favelas do noroeste do país promovem atitudes favoráveis à inclusão social das pessoas deslocadas, a maioria ciganos. Para isso, foi feito um questionário que captura as percepções de dois grupos: os que foram reassentados e as pessoas que os recebem em seus bairros. -

Restricciones Aplicables a Galicia 15 Enero De 2021

RESTRICCIONES APLICABLES A GALICIA 15 ENERO DE 2021 Mediante Decreto 3/2021, de 13 de enero, de la Presidencia de la Xunta de Galicia, y Orden de 13 de enero de 2021 de la Consellería de Sanidad, se regulan nuevas modificaciones a las restricciones aplicables al ámbito de nuestra Comunidad Autónoma. Se mantienen las obligaciones de cautela y protección, obligatoriedad de mascarilla, mantenimiento de seguridad interpersonal, higiene y prevención. Toda Galicia entra en nivel medio-alto o en nivel de máximas restricciones, no quedando ya ningún municipio en nivel básico ni medio. LIMITACION DE LA MOVILIDAD NOCTURNA Con efectos desde las 00:00 horas del 15 de enero de 2021, el denominado “toque de queda” queda establecido desde las 22:00 horas. Durante el período comprendido entre las 22:00 y las 6:00 horas, las personas únicamente pueden circular por las vías o espacios de uso público para realizar las siguientes actividades: a) Adquisición de medicamentos, productos sanitarios y otros bienes de primera necesidad. b) Asistencia a centros, servicios y establecimientos sanitarios. c) Asistencia a centros de atención veterinaria por motivos de urgencia. d) Cumplimento de obligaciones laborales, profesionales, empresariales, institucionales o legales. e) Retorno al lugar de residencia habitual tras realizar algunas de las actividades previstas en este apartado. f) Asistencia y cuidado de mayores, menores, dependientes, personas con discapacidad o personas especialmente vulnerables. g) Por causa de fuerza mayor o situación de necesidad. h) Cualquier -

La Rueda De La Fortuna De Nebrixe (Bribes, Cambre, a Coruña)1

LaLA Rueda RUEDA DE LA FORTUNAde la DE NEBRIXEFortuna (BRIBES, CAMBRE, de Nebrixe A CORUÑA) (Bribes, Cambre, A Coruña)1 CARLOS SASTRE* Oh, Fortuna Sumario velut luna La inédita Rueda de la Fortuna de Nebrixe es analizada en un amplio contexto status variabilis ideológico. […] Abstract: Sors immanis The hitherto unknown Wheel of Fortune in Nebrixe is studied within a broad et inanis, ideological context. rota tu volubilis Carmina Burana 1. INTRODUCCIÓN «¡Ah! ¡Qué infelizmente para mí ha girado tu rueda, Fortuna! Ayer estaba arriba y hoy abajo. Ayer era feliz y hoy desgraciado. Ayer me sonreías, hoy me llenas de llanto». Así se lamenta Lancelot, uno de los héroes de Chrétien de Troyes (floruit 1164-1190), el prolífico poeta francés autor de la saga caballeresca más importante de la Edad Media2. El texto trae de inmediato a la memoria imágenes como la soberbia miniatura del Hortus Deliciarum, enciclopédica obra encargada por la abadesa Herrade de Hohenburg (Fig. 1), en la que Fortuna es personificada como una dama que, sentada en un lujoso trono, mueve incesante una rueda, la del destino de los hombres, mostrando lo transitorio de la fama, el poder o los honores mundanos3. Aunque el contexto es aquí la literatura cortés del siglo XII, las raíces del motivo de Fortuna moviendo su rueda y cambiando a su antojo la suerte de la Humanidad han de buscarse mucho más atrás. 2. ORIGEN DEL TEMA La diosa Fortuna, que alcanzó una más que notable preponderancia en la religión imperial romana, es presentada en la numismática con ciertos atributos que aluden a su carácter inconstante, como la rueda, normalmente situada bajo su trono, o la esfera4. -

2020 09 15 Doazon Sangue a Positivo E B Positivo.Pdf

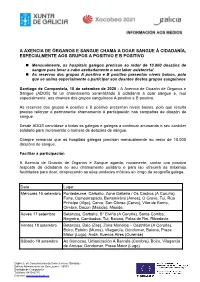

A AXENCIA DE ÓRGANOS E SANGUE CHAMA A DOAR SANGUE Á CIDADANÍA, ESPECIALMENTE AOS GRUPOS A POSITIVO E B POSITIVO Mensualmente, os hospitais galegos precisan ao redor de 10.000 doazóns de sangue para levar a cabo axeitadamente o seu labor asistencial As reservas dos grupos A positivo e B positivo presentan niveis baixos, polo que se anima especialmente a participar aos doantes destes grupos sanguíneos Santiago de Compostela, 15 de setembro de 2020.- A Axencia de Doazón de Órganos e Sangue (ADOS) fai un chamamento xeneralizado á cidadanía a doar sangue e, moi especialmente, aos doantes dos grupos sanguíneos A positivo e B positivo. As reservas dos grupos A positivo e B positivo presentan niveis baixos, polo que resulta preciso reforzar o permanente chamamento á participación nas campañas de doazón de sangue. Desde ADOS convídase a todas as galegas e galegos a continuar amosando o seu carácter solidario para incrementar o numero de doazóns de sangue. Cómpre remarcar que os hospitais galegos precisan mensualmente ao redor de 10.000 doazóns de sangue. Facilitar a participación A Axencia de Doazón de Órganos e Sangue agarda, novamente, contar coa positiva resposta da cidadanía ao seu chamamento solidario e para iso ofrecerá as máximas facilidades para doar, desprazando as súas unidades móbiles ao longo da xeografía galega. Data Lugar Mércores 16 setembro Pontedeume, Carballo, Zona Gaiteira / Os Castros (A Coruña), Forte, Camporrapado, Bertamiráns (Ames), O Grove, Tui, Rúa Príncipe (Vigo), Cervo, San Cibrao (Cervo), Vilar de Barrio, Oimbra, Dacon (Maside), Maside. Xoves 17 setembro Betanzos, Carballo, Bº Elviña (A Coruña), Santa Comba, Negreira, Cambados, Tui, Baiona, Palas de Rei, Ribadavia Venres 18 setembro Betanzos, Baio (Zas), Zona Monelos – Castrillón (A Coruña), Boiro, Esteiro (Muros), Vilagarcía, Gondomar, Baiona, Praza Maior (Lugo), Avda. -

Relación De Centros De Servizos Sociais De a Coruña

CONCELLO ENDEREZO SS.SS CP TEL. SS.SS EMAIL SS.SS. ABEGONDO SAN MARCOS, S/N 15318 981647996 [email protected] AMES PRAZA DE CHAVIAN, S/N, BERTAMIRANS 15220 981890964 [email protected] ARANGA PRAZA DO MESTRE MOSQUERA 1 15317 981793551 [email protected] ARES AVDA SAAVEDRA MENESES 12 15624 981468102 [email protected] ARTEIXO R/ NOIA, 2, BAIXO 15142 981659110 [email protected] ARZÚA R/SANTIAGO 2 15810 981815297 [email protected] BAÑA (A) PRAZA DO CONCELLO 1 15863 981886501 [email protected] BERGONDO ESTRADA A CORUÑA, 12 15165 981791252 [email protected] BETANZOS PRAZA DO EMIGRANTE 1 15300 981770707 [email protected] BOIMORTO VILANOVA S/N 15817 981516075 [email protected] BOIRO PRAZA DE GALICIA S/N 15930 981844800 [email protected] BOQUEIXÓN O FORTE 15881 981513106 [email protected] BRIÓN CENTRO SOCIAL POLIVALENTE, PEDROUZOS 981509910 [email protected] CABANA DE A CARBALLA S/N- CESULLAS 15115 981754020 [email protected] BERGANTIÑOS CABANAS RUA DO CONCELLO 3 15621 981495959 [email protected] CAMARIÑAS PRAZA DE INSUELA 15123 981737004 [email protected] CAMBRE RIO BARCÉS, 8, A BARCALA 15660 981654812 [email protected] CAPELA (A) AS NEVES 46A 15613 981459006 [email protected] CARBALLO PLAZA MEDICO EDUARDO MARIÑO, S/N 15100 981704706 [email protected] CARIÑO AVDA DA PAZ 2 15360 981420059 [email protected] CARNOTA PZA. SAN GREGORIO, 19 15293 981857032 [email protected] CARRAL EDIF. ADMVO. TOÑITO ESPIÑEIRO, RUA MENDEZ BUA, S/N 15175 981613520 [email protected] [email protected], CEDEIRA RUA CONVENTO, S/N, 3º 15350 607409698 [email protected] CEE DOMINGO A. -

Cuadro Médico Adeslas a Coruña

Cuadro Médico 2020 | A CORUÑA Médico Cuadro Cuadro Médico 2020 CUADRO MÉDICO 20202019 91 919 18 98 A CORUÑA 93 518 10 80 www.segurcaixaadeslas.es ESTE LIBRO ESTÁ IMPRESO CON PAPEL DE FUENTES RESPONSABLES Y SOSTENIBLES SegurCaixa Adeslas, S.A. de Seguros y Reaseguros, con domicilio social en el Paseo de la Castellana, 259 C (Torre de Cristal), 28046 Madrid, con NIF A28011864, e inscrita en el R. M. de Madrid, tomo 36733, folio 213, hoja M-658265. S.RE. 155/14 001-002 Sumario.qxp 10/10/14 06:05 Página 1 ÍNDICE GENERAL PRESENTACIÓN ................................................................................................................. 5 ATENCIÓN LAS 24 HORAS .................................................................................................. 7 SERVICIOS DE URGENCIA 9 URGENCIAS A CORUÑA .................................................................................................... 11 URGENCIAS SANTIAGO DE COMPOSTELA .............................................................................. 11 URGENCIAS EL FERROL ..................................................................................................... 12 URGENCIAS CARBALLO....................................................................................................... 12 URGENCIAS CULLEREDO .................................................................................................... 12 URGENCIAS OLEIROS ........................................................................................................ 12 URGENCIAS RIBEIRA ........................................................................................................ -

Citizen Action As a Driving Force of Change. the Meninas of Canido, Art in the Street As an Urban Dynamizer

sustainability Article Citizen Action as a Driving Force of Change. The Meninas of Canido, Art in the Street as an Urban Dynamizer María José Piñeira Mantiñán * , Francisco R. Durán Villa and Ramón López Rodríguez Department of Geography, University of Santiago de Compostela, 15782 Santiago de Compostela, Galicia, Spain; [email protected] (F.R.D.V.); [email protected] (R.L.R.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-88181100 (ext. 12626) Received: 20 December 2019; Accepted: 15 January 2020; Published: 20 January 2020 Abstract: The austerity policies imposed by the government in the wake of the 2007 crisis have deteriorated the welfare state and limited neighborhood recovery. Considering the inability and inefficiency on the part of administrations to carry out improvement actions in neighborhoods, it is the neighborhood action itself that has carried out a series of resilient social innovations to reverse the dynamics. In this article, we will analyze the Canido neighborhood in Ferrol, a city in north-western Spain. Canido is traditional neighborhood that was experiencing a high degree of physical and social deterioration, until a cultural initiative called “Meninas of Canido,” promoted by one of its artist neighbors, recovered its identity and revitalized it from a physical, social, and economic point of view. Currently, the Meninas of Canido has become one of the most important urban art events in Spain and has receives international recognition. The aim of this article is to evaluate the impact that this action has had in the neighborhood. For this, we conducted a series of semi-structured interviews with the local administration, neighborhood association, the precursors of this idea, merchants, and some residents in general, in order to perceive the reception and evolution of this action. -

![The Road to Santiago Cubertas: Barro Salgado Santana [Grupo Revisión Deseño] Cubertas: Barro](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0601/the-road-to-santiago-cubertas-barro-salgado-santana-grupo-revisi%C3%B3n-dese%C3%B1o-cubertas-barro-2420601.webp)

The Road to Santiago Cubertas: Barro Salgado Santana [Grupo Revisión Deseño] Cubertas: Barro

"You say: Galicia is very small. And I say: there is a World of Galicia. Every piece of a land is in itself as the entire World. You may journey from North to South, from East to West, in little time; you may do so over and over again, and yet you shall not travel it whole. And every time you go, you shall come across new things (...) The surface may be small; in depth, entity, Galicia is as great as you wish ... " VICENTE RISCO www.turgalicia.es the Road to Santiago Cubertas: Barro Salgado Santana [Grupo Revisión Deseño] Cubertas: Barro Dirección Xeral de Turismo HOSTELS ON THE FRENCH ROAD LOCATION COUNCIL NUMBER OF PLACES CONTENTS (1) CEBREIRO PEDRAFITA DO CEBREIRO 80 (1) HOSPITAL DA CONDESA PEDRAFITA DO CEBREIRO 18 (1) TRIACASTELA TRIACASTELA 60 (1) CALVOR SARRIA 22 The Road to Santiago (1) SARRIA SARRIA 48+2 (1) BARBADELO SARRIA 22 (1) FERREIROS PARADELA 22 3 HELSINKI (1) PORTOMARÍN PORTOMARÍN 40 Setting Off (1) GONZAR PORTOMARÍN 20 STOCKHOLM (1) VENTAS DE NARÓN PORTOMARÍN 22 (1) LIGONDE MONTERROSO 18 4 (1) PALAS DE REI PALAS DE REI 49 DUBLIN COPENHAGEN (1) MATO CASANOVA PALAS DE REI 20 Towards Santiago (1) MELIDE MELIDE 130 LONDON AMSTERDAN (1) RIBADISO ARZÚA 62 5 (1) SANTA IRENE O PINO 36 BRUSSELS BERLIN (1) ARCA O PINO 80 The French Road (1) MONTE DO GOZO SANTIAGO DE COMPOSTELA 800 PARIS LUXEMBOURG (2) ARZÚA ARZÚA 46+2 VIENNA 6 GALICIA The Road from the North HOSTELS ON THE FISTERRA-MUXIA ROAD LOCATION COUNCIL NUMBER OF PLACES LISBON MADRID 14 ROME (1) FISTERRA FISTERRA 16+1 NEGREIRA NEGREIRA The Silver Route ATHENS 16 HOSTELS -

Culture and Society in Medieval Galicia

Culture and Society in Medieval Galicia A Cultural Crossroads at the Edge of Europe Edited and Translated by James D’Emilio LEIDEN | BOSTON For use by the Author only | © 2015 Koninklijke Brill NV <UN> Contents Preface ix Acknowledgments xxiv List of Figures, Maps, and Tables XXVI Abbreviations xxxii List of Contributors xxxviii Part 1: The Paradox of Galicia A Cultural Crossroads at the Edge of Europe 1 The Paradox of Galicia A Cultural Crossroads at the Edge of Europe 3 James D’Emilio Part 2: The Suevic Kingdom Between Roman Gallaecia and Modern Myth Introduction to Part 2 126 2 The Suevi in Gallaecia An Introduction 131 Michael Kulikowski 3 Gallaecia in Late Antiquity The Suevic Kingdom and the Rise of Local Powers 146 P. C. Díaz and Luis R. Menéndez-Bueyes 4 The Suevic Kingdom Why Gallaecia? 176 Fernando López Sánchez 5 The Church in the Suevic Kingdom (411–585 ad) 210 Purificación Ubric For use by the Author only | © 2015 Koninklijke Brill NV <UN> vi Contents Part 3: Early Medieval Galicia Tradition and Change Introduction to Part 3 246 6 The Aristocracy and the Monarchy in Northwest Iberia between the Eighth and the Eleventh Century 251 Amancio Isla 7 The Charter of Theodenandus Writing, Ecclesiastical Culture, and Monastic Reform in Tenth- Century Galicia 281 James D’ Emilio 8 From Galicia to the Rhône Legal Practice in Northern Spain around the Year 1000 343 Jeffrey A. Bowman Part 4: Galicia in the Iberian Kingdoms From Center to Periphery? Introduction to Part 4 362 9 The Making of Galicia in Feudal Spain (1065–1157) 367 Ermelindo Portela 10 Galicia and the Galicians in the Latin Chronicles of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries 400 Emma Falque 11 The Kingdom of Galicia and the Monarchy of Castile-León in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries 429 Francisco Javier Pérez Rodríguez For use by the Author only | © 2015 Koninklijke Brill NV <UN> Contents vii Part 5: Compostela, Galicia, and Europe Galician Culture in the Age of the Pilgrimage Introduction to Part 5 464 12 St. -

Anuncio 24202 Del BOE Núm. 171 De 2011

BOLETÍN OFICIAL DEL ESTADO Núm. 171 Lunes 18 de julio de 2011 Sec. V-B. Pág. 78699 V. Anuncios B. Otros anuncios oficiales COMUNIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE GALICIA 24202 Orden del 7 de julio de 2011, de la Consellería de Economía e Industria, por la que se convoca concurso público de los terrenos francos resultantes de la declaración de caducidad de derechos mineros correspondientes a la provincia de A Coruña. La Ley 3/2008, del 23 de mayo, de Ordenación de la Minería de Galicia (en adelante LOMINGA) constituye la legislación propia de la Comunidad Autónoma en materia de minas y desarrolla el régimen jurídico de las actividades mineras en Galicia en condiciones de sostenibilidad y seguridad, promoviendo un aprovechamiento racional de los recursos compatible con la protección del medio ambiente. En su Título IV regula el procedimiento de otorgamiento y contenido de los derechos mineros, estableciendo en el artículo 35 que los terrenos francos resultantes del levantamiento de una zona de reserva o la declaración de caducidad de un permiso de exploración, un permiso de investigación o una concesión minera podrán ser declarados registrables una vez celebrado el necesario concurso público previsto en la legislación específica minera. Dicha legislación específica minera está constituida por la Ley 22/1973, del 21 de julio, de Minas y sus modificaciones posteriores, desarrollada por el Reglamento General para el Régimen de la Minería aprobado por el Real Decreto 2857/1978, del 25 de agosto. El artículo 39 de la Ley de Minas señala que el levantamiento de la reserva o la caducidad del permiso de exploración, del permiso de investigación o de la concesión de explotación no otorgará al terreno el carácter registrable hasta que tenga lugar un concurso público por el que se resolverá, conforme a los artículos 53 y 64, el otorgamiento de permisos de investigación y concesiones directas de explotación sobre dichos terrenos. -

BOE 021 De 25/01/2005 Sec 5 Pag 589 A

BOE núm. 21 Martes 25 enero 2005 589 1.671/05. Anuncio de la Demarcación de Costas en Regueira Álvarez, Eliseo y Manuel (Cambre, s/n, en el artículo 44 de la Ley 29/1998, de 13 de julio, regu- Galicia sobre notificación de la Orden Ministe- Lema-Carballo). ladora de la Jurisdicción Contencioso-Administrativa. rial de 7 de septiembre de 2004 aprobando el Regueira Ferreiro, Fidel (Cervantes, 4-Carballo). Los plazos serán contados desde el día siguiente a la deslinde de los bienes de dominio público maríti- Regueira Ferreiro, Ramón (Cervantes, 4-Carballo). práctica de la notificación de la presente resolución. Regueira, Jesús (Rapadoiro-Noicela-Carballo). mo-terrestre del tramo de costa de unos dieciséis Rey Patiño, Antonio (Rebordelos-Vilela-Carballo). A Coruña, 4 de enero de 2005.–El Jefe de la Demarca- mil seiscientos cuarenta y cinco (16.645) metros Rodríguez Castiñeiras, Ricardo (Emilia Pardo Bazán, 18, ción de Costas en Galicia en Funciones, Rafael Eimil de longitud, comprendido desde el límite del tér- Vilela-Carballo). Apenela. mino municipal Laracha-Carballo hasta las pla- Rodríguez Collazo, Ramón (Cambre, 10, Lema-Car- yas y marismas de Razo-Baldaio, en el término ballo). municipal de Carballo (A Coruña). Rodríguez Lista, María (Razo da Costa, 66, Razo-Car- ballo). 1.674/05. Resolución de la Confederación Hidro- La Demarcación de Costas en Galicia, en cumplimien- Rodríguez Maroño, Juan (Meicende-Arteixo (Talleres gráfica del Júcar autorizando la incoación del to de lo dispuesto por el artículo 59.4 de la Ley 30/1992, de Barbeito). expediente de información pública del estudio de 26 de noviembre, de Régimen Jurídico de las Adminis- Rodríguez Mato, Jesús (Casadelas, 3, Noicela-Carballo).