Copyright by Tricia Marie Jokerst August 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tenure for 20 Teachers

TUESDAY 162nd YEAR • No. 217 JANUARY 10, 2017 CLEVELAND, TN 16 PAGES • 50¢ Finance leaders to review county credit card policy By BRIAN GRAVES finances issued a finding that several officials that their privileges would be in you lose a receipt on a certain date, you point to see that all of those receipts are Banner Staff Writer departments did not follow the county’s jeopardy, if they did not conform to the have to write a memo saying you had there.” policy in 219 of 430 uses in 2016. county policies. this much of a purchase on the certain He said some receipts are not detailed The issue of credit card usage by The audit cited 52 purchases which Concerning the credit cards, Davis date for this county car and turn it in and have to be noted by hand as to the county employees will be heading to the did not have detailed receipts and 167 said each department received an with the bill. That will work,” Davis specifics of the bill. Finance Committee of the Bradley receipts which were not signed. accounting of their violations and card explained. “Maybe they did not know “All department heads have agreed County Commission. State auditors did not report any mis- usage is being monitored for proper doc- that extra step. When receipts were lost, those would be corrected and not be an Commissioner Thomas Crye, a mem- use of the credit cards. umentation. they were just turning the bills in and issue again next year,” Davis said. ber of that committee, requested the Bradley County Mayor D. -

TAL Direct: Sub-Index S912c Index for ASIC

TAL.500.002.0503 TAL Direct: Sub-Index s912C Index for ASIC Appendix B: Reference to xv: A list of television programs during which TAL’s InsuranceLine Funeral Plan advertisements were aired. 1 90802531/v1 TAL.500.002.0504 TAL Direct: Sub-Index s912C Index for ASIC Section 1_xv List of TV programs FIFA Futbol Mundial 21 Jump Street 7Mate Movie: Charge Of The #NOWPLAYINGV 24 Hour Party Paramedics Light Brigade (M-v) $#*! My Dad Says 24 HOURS AFTER: ASTEROID 7Mate Movie: Duel At Diablo (PG-v a) 10 BIGGEST TRACKS RIGHT NOW IMPACT 7Mate Movie: Red Dawn (M-v l) 10 CELEBRITY REHABS EXPOSED 24 hours of le mans 7Mate Movie: The Mechanic (M- 10 HOTTEST TRACKS RIGHT NOW 24 Hours To Kill v a l) 10 Things You Need to Know 25 Most Memorable Swimsuit Mom 7Mate Movie: Touching The Void 10 Ways To Improve The Value O 25 Most Sensational Holly Melt -CC- (M-l) 10 Years Younger 28 Days in Rehab 7Mate Movie: Two For The 10 Years Younger In 10 Days Money -CC- (M-l s) 30 Minute Menu 10 Years Younger UK 7Mate Movie: Von Richthofen 30 Most Outrageous Feuds 10.5 Apocalypse And Brown (PG-v l) 3000 Miles To Graceland 100 Greatest Discoveries 7th Heaven 30M Series/Special 1000 WAYS TO DIE 7Two Afternoon Movie: 3rd Rock from the Sun 1066 WHEN THREE TRIBES WENT 7Two Afternoon Movie: Living F 3S at 3 TO 7Two Afternoon Movie: 4 FOR TEXAS 1066: The Year that Changed th Submarin 112 Emergency 4 INGREDIENTS 7TWO Classic Movie 12 Disney Tv Movies 40 Smokin On Set Hookups 7Two Late Arvo Movie: Columbo: 1421 THE YEAR CHINA 48 Hour Film Project Swan Song (PG) DISCOVERED 48 -

CCU's Track Goes Teal

Coastal Carolina University CCU Digital Commons The hC anticleer Student Newspaper Kimbel Library and Bryan Information Commons 9-29-2017 The hC anticleer, 2017-09-29 Coastal Carolina University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/chanticleer Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Coastal Carolina University, "The hC anticleer, 2017-09-29" (2017). The Chanticleer Student Newspaper. 652. https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/chanticleer/652 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Kimbel Library and Bryan Information Commons at CCU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The hC anticleer Student Newspaper by an authorized administrator of CCU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. thechanticleernews.com 09.29.07 CCU’s track goes teal Shaving heads Issue 03 Katelin Gandee // Reporter “It’s more than just a color. It’s something for cancer that’s the fabric and mentality of our whole Kaley Lawrimore // Editor-in-Chief In the next four to six weeks, CCU will be campus,” Hogue said. “It’s who we are.” gaining yet another teal addition. Fowler also said CCU will be hosting The Coop Bar and Grill is hosting its The new teal track is currently being laid their own track meets because of the new 2nd Annual Shaving Heads for Cancer down at the track and field facility. Connor track. event to raise money for those who have Sports, the company hired to remodel the “A North Carolina versus South Carolina been impacted by breast cancer. -

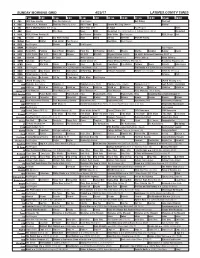

Sunday Morning Grid 4/23/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/23/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Bull Riding PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A.: Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Beverly Hills Dog Show Å Hockey 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program News 7 ABC News This Week News NBA Basketball Cleveland Cavaliers at Indiana Pacers. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Weird DIY Sci NASCAR NASCAR Racing 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Cooking Baking Sara’s 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bali (TVG) Bali (TVG) Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Migrant Kitchen (10:02) Ed Slott’s Retirement Roadmap 2017 Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch White Collar Å White Collar Wanted. White Collar Å White Collar Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Madeline ››› (1998) Frances McDormand. -

Lugar Warns U.S. Against War in Libya Oil Facilities in Susan Cornwell (Front Row in Afghanistan and Iraq, As Well Washington) As Somalia, Where a U.S

Newstablet Edition - 09/03/11 http://www.LibertyNewspost.com Gadhafi forces hit Lugar warns U.S. against war in Libya oil facilities in Susan Cornwell (Front Row in Afghanistan and Iraq, as well Washington) as Somalia, where a U.S. central Libya (AP) Submitted at 3/8/2011 7:51:08 PM humanitarian mission went (Yahoo! News: Most Popular) wrong in the 1990s, “the burden In recent days some U.S. of proof lies on those calling for Submitted at 3/9/2011 12:43:25 PM senators have been urging military intervention to AP - Forces loyal to Moammar President Obama to consider demonstrate that doing so would Gadhafi struck an oil pipeline and military intervention to help be in the United States’ national oil storage facility Wednesday, Libyan rebels fighting Moammar interest,” Lugar declared. sending a giant yellow fireball Gaddafi. And: A major mlitary action to into the sky as they pounded Not Richard Lugar. support anti-Gaddafi forces rebels with artillery and gunfire in The top Republican on the Senate would require a declaration of war at least two major cities. foreign relations committee said by Congress, Lugar said. little while a senior member of Something for his fellow senators, his own party, John McCain, as well as President Obama, to repeatedly urged the United States consider. Fire in central to pursue setting up a no-fly zone Photo Credits: Reuters/Gleb over Libya. Garanich (Lugar at news Pa. farmhouse On Sunday Democrat John conference in Kiev, August 29, Kerry, the chairman of the foreign kills 7 kids (AP) consequences and implications,” Afghanistan and Iraq, he warned. -

List of Programs Broadcast by the Arutz Hayeladim

List of programs broadcast by the Arutz HaYeladim This is a list of television programs formerly broadcast by the U.S. cable television channel G4. 10 Play. 2 Months 2 Million (2009; 2014; reruns). American Ninja Warrior (2009â“2013). Arena (2002â“2005). Attack of the Show! (2005â“2013). Blister (2002â“2004). The Block (2007). Body Hits (2004). Bomb Patrol Afghanistan (2011â“2013). Boost Mobile MLG Pro Circuit (2007). Campus PD (2009â“2012; 2012â“2014; reruns). Cheat! (2002â“2006). Code Monkeys (2007â“2008). Cinematech (2002â“2007). Arutz HaYeladim's wiki: Arutz HaYeladim (Hebrew: ערוץ הילדי×âŽ, The Kids' Channel) is an Israeli youngster cable television channel owned by RGE (and formerly NOGA Communications Limited). It was one of the first cable channels in Israel, along with Arutz HaMishpaha, Arutz HaSrat. See also. List of programs broadcast by the Arutz HaYeladim. Image & Video Gallery. Michal Yannai in Arutz HaYeladim. Reference Links For This Wiki. All information for Arutz HaYeladim's wiki comes from the below links. Any source is valid, including Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn. Pictures, videos, biodata, and files relating to Arutz HaYeladim are also acceptable encyclopedic sources. In 2016, Arutz Hayeladim started to air DreamWorks Animation shows, including: 2015 [ edit ]. Turbo FAST. Lists of TV programs broadcast by country. Asia-wide. In August 2011, Arutz Hayeladim started to air a block of Cartoon Network shows, including: Adventure Time. Almost Naked Animals. The Amazing World of Gumball. Angelo Rules. Baby Looney Tunes. Bakugan Battle Brawlers (season 3 and 4). Lists of TV programs broadcast by country. Asia-wide. -

Luke Bryan Concert at the Wharf on the Island This Week, You May Run Into In-State Spring Breakers from Faulkner University and the Montgomery County Schools

COMMUNITY CALENDAR: Ongoing and Upcoming Events, PAGE 5 Florida Georgia Line coming to Orange Beach The Islander PAGE 39 INSIDE MARCH 22, 2017 | GulfCoastNewsToday.com | 75¢ This week’s Spring Breakers While out and about Luke Bryan concert at The Wharf on the Island this week, you may run into in-state Spring Breakers from Faulkner University and the Montgomery County schools. St. Patrick’s Day Pub Crawl Last week saw the return of the be- loved annual Gulf Shores St. Patrick’s Day Walking Parade and Pub Crawl. For pictures of all the fun festivities from this year’s event, turn to PHOTOS BY CAPT. MARK ROBINSON Page 6. It was a fun time in Orange Beach last week as Luke Bryan visited The Wharf Friday for an amazing concert. The seats were packed as people enjoyed Bryan and his opening acts, Brett Young and Brett Eldredge. For more photos from this event, turn to Page 2 or visit our website at gulfcoastnewstoday.com. School Gulf Shores board residents speak out on beach recognizes access issues Orange Beach Concierge gains GSHS Council passes new chef Acclaimed local Chef students Hangout Festival, Sam McLeod has joined on with the Three helped retail study team at Orange Beach BCBE Board Member Angie Swiger recognizes several people for their Concierge. To learn victims injured in work and help in the aftermath of the Gulf Shores Mardi Gras parade agreements more about this, turn accident in which 12 students were transported to local hospitals for injuries. By CRYSTAL COLE to Page 38. parade accident [email protected] STAFF REPORT professionalism and calm in a trying time. -

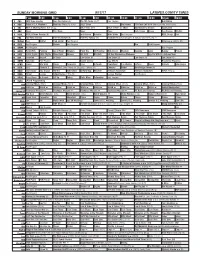

Sunday Morning Grid 9/17/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/17/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Paid Program Bull Riding 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) 2017 Evian Presidents PGA Tour Golf BMW Championship, Final Round. 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am Countdown to Emmys Countdown 7 ABC News This Week News News Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Philadelphia Eagles at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Drive ››› (2011) (R) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program The Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Cooking Jazzy Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ 28 Day Metabolism Makeover Age Fix With Dr. Anthony Youn 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Central Liga MX (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio de Singapur: Carrera. -

Crystal Reports

VITAL/EXPANDED TECHNOLOGIES INITIATIVE FY 2018-2019 PROPOSALS Proposal ID: 39 Division Academic Affairs College of Arts and Letters 47228 Campus Division David Carlson [email protected] 909-537-5834 Total Amount Requested for FY 2017 $45,357.00 Project Title: Mobile Laptop Labs for English Courses and Advising Project Abstract: The English Department requests funding for two 30-laptop mobile labs to enhance student learning in multiple classes, and to be used by the department for group advising sessions as we work through the semester conversion and towards overall improvement in graduation rates. One of these labs will be housed at the San Bernardino campus and the other will be housed at the Palm Desert campus. These labs will serve the many sections of first-year composition (ENG 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107) and expository writing (ENG 306) taken each quarter by students from all different majors. In these courses, the laptops will help students to learn how to conduct online research; complete collaborative writing projects; and incorporate real-time feedback from their peers and instructors into their writing. In addition, in our English literature, creative writing, and linguistics courses taken by English majors and Liberal Studies majors, the laptops will allow students to research digital archives on authors and texts; to use online "corpus linguistics" tools to examine word usage in real- life discourse; and to produce a range of multimedia texts. Our department has just hired a new creative writing faculty member with expertise in digital publication and multi-modal creative writing; we expect this faculty member to regularly employ these labs in her courses. -

Thomason Given Norwood Veterans Service Award

SPORTS: LOCAL NEWS: Preds comeback Owens Corning falls short in honors Armed Forces Game 1: Page 9 members: Page 8 163rd Year • No. 26 16 paGes • 50¢ CLEVELAND, TN 37311 THE CITY WITH SPIRIT TUESDAY, MAY 30, 2017 Cleveland No. 21 for job growth By LARRY C. BOWERS [email protected] The city of Cleveland is preparing to carry its economic success of the past fiscal year into a new one. Cleveland was ranked No. 1 in the nation last year in municipal job growth, and now ranks high Banner photos, DaNieL GUY on a new list of American cities & LarrY BOWers for future job growth. Thomason given Newgeography.com ranks U.s. NaVaL sea Cleveland 21st on its list of 250 CaDeTs, Chattanooga “Best Cities For Job Growth.” Division, above left, pre- This ranking displays lofty sented the colors at the Norwood Veterans expectations for the city with the 2017 Veteran's Day obser- opening of the new Spring vation at the Bradley Branch Industrial Park south of County Courthouse Square the city, and the anticipation of on Monday. Service Award 2,000 or more new jobs during the coming months. U.s. air Force Col. Newgeography is a website cre- Charles Murray, center, By LARRY C. BOWERS ated in 2008 by Praxis Strategy delivers the address. [email protected] Group. Praxis develops economic WOrLD War ii Marine Like tears from heaven, a sprin- strategies for clients in business, veteran Jack Murphy kling of Monday morning raindrops industry, communities and pub- salutes the flag during the concluded a somber and solemn lic-private partnerships.