Hierarchy Without a Head: Observations on Changes in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P E E L C H R Is T Ian It Y , Is L a M , an D O R Isa R E Lig Io N

PEEL | CHRISTIANITY, ISLAM, AND ORISA RELIGION Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and rein- vigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org Christianity, Islam, and Orisa Religion THE ANTHROPOLOGY OF CHRISTIANITY Edited by Joel Robbins 1. Christian Moderns: Freedom and Fetish in the Mission Encounter, by Webb Keane 2. A Problem of Presence: Beyond Scripture in an African Church, by Matthew Engelke 3. Reason to Believe: Cultural Agency in Latin American Evangelicalism, by David Smilde 4. Chanting Down the New Jerusalem: Calypso, Christianity, and Capitalism in the Caribbean, by Francio Guadeloupe 5. In God’s Image: The Metaculture of Fijian Christianity, by Matt Tomlinson 6. Converting Words: Maya in the Age of the Cross, by William F. Hanks 7. City of God: Christian Citizenship in Postwar Guatemala, by Kevin O’Neill 8. Death in a Church of Life: Moral Passion during Botswana’s Time of AIDS, by Frederick Klaits 9. Eastern Christians in Anthropological Perspective, edited by Chris Hann and Hermann Goltz 10. Studying Global Pentecostalism: Theories and Methods, by Allan Anderson, Michael Bergunder, Andre Droogers, and Cornelis van der Laan 11. Holy Hustlers, Schism, and Prophecy: Apostolic Reformation in Botswana, by Richard Werbner 12. Moral Ambition: Mobilization and Social Outreach in Evangelical Megachurches, by Omri Elisha 13. Spirits of Protestantism: Medicine, Healing, and Liberal Christianity, by Pamela E. -

The Journey of Vodou from Haiti to New Orleans: Catholicism

THE JOURNEY OF VODOU FROM HAITI TO NEW ORLEANS: CATHOLICISM, SLAVERY, THE HAITIAN REVOLUTION IN SAINT- DOMINGUE, AND IT’S TRANSITION TO NEW ORLEANS IN THE NEW WORLD HONORS THESIS Presented to the Honors College of Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation in the Honors College by Tyler Janae Smith San Marcos, Texas December 2015 THE JOURNEY OF VODOU FROM HAITI TO NEW ORLEANS: CATHOLICISM, SLAVERY, THE HAITIAN REVOLUTION IN SAINT- DOMINGUE, AND ITS TRANSITION TO NEW ORLEANS IN THE NEW WORLD by Tyler Janae Smith Thesis Supervisor: _____________________________ Ronald Angelo Johnson, Ph.D. Department of History Approved: _____________________________ Heather C. Galloway, Ph.D. Dean, Honors College Abstract In my thesis, I am going to delve into the origin of the religion we call Vodou, its influences, and its migration from Haiti to New Orleans from the 1700’s to the early 1800’s with a small focus on the current state of Vodou in New Orleans. I will start with referencing West Africa, and the religion that was brought from West Africa, and combined with Catholicism in order to form Vodou. From there I will discuss the effect a high Catholic population, slavery, and the Haitian Revolution had on the creation of Vodou. I also plan to discuss how Vodou has changed with the change of the state of Catholicism, and slavery in New Orleans. As well as pointing out how Vodou has affected the formation of New Orleans culture, politics, and society. Introduction The term Vodou is derived from the word Vodun which means “spirit/god” in the Fon language spoken by the Fon people of West Africa, and brought to Haiti around the sixteenth century. -

View Centro's Film List

About the Centro Film Collection The Centro Library and Archives houses one of the most extensive collections of films documenting the Puerto Rican experience. The collection includes documentaries, public service news programs; Hollywood produced feature films, as well as cinema films produced by the film industry in Puerto Rico. Presently we house over 500 titles, both in DVD and VHS format. Films from the collection may be borrowed, and are available for teaching, study, as well as for entertainment purposes with due consideration for copyright and intellectual property laws. Film Lending Policy Our policy requires that films be picked-up at our facility, we do not mail out. Films maybe borrowed by college professors, as well as public school teachers for classroom presentations during the school year. We also lend to student clubs and community-based organizations. For individuals conducting personal research, or for students who need to view films for class assignments, we ask that they call and make an appointment for viewing the film(s) at our facilities. Overview of collections: 366 documentary/special programs 67 feature films 11 Banco Popular programs on Puerto Rican Music 2 films (rough-cut copies) Roz Payne Archives 95 copies of WNBC Visiones programs 20 titles of WNET Realidades programs Total # of titles=559 (As of 9/2019) 1 Procedures for Borrowing Films 1. Reserve films one week in advance. 2. A maximum of 2 FILMS may be borrowed at a time. 3. Pick-up film(s) at the Centro Library and Archives with proper ID, and sign contract which specifies obligations and responsibilities while the film(s) is in your possession. -

Yoruba Art & Culture

Yoruba Art & Culture Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Yoruba Art and Culture PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Written and Designed by Nicole Mullen Editors Liberty Marie Winn Ira Jacknis Special thanks to Tokunbo Adeniji Aare, Oduduwa Heritage Organization. COPYRIGHT © 2004 PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY ◆ UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT BERKELEY BERKELEY, CA 94720-3712 ◆ 510-642-3682 ◆ HTTP://HEARSTMUSEUM.BERKELEY.EDU Table of Contents Vocabulary....................4 Western Spellings and Pronunciation of Yoruba Words....................5 Africa....................6 Nigeria....................7 Political Structure and Economy....................8 The Yoruba....................9, 10 Yoruba Kingdoms....................11 The Story of How the Yoruba Kingdoms Were Created....................12 The Colonization and Independence of Nigeria....................13 Food, Agriculture and Trade....................14 Sculpture....................15 Pottery....................16 Leather and Beadwork....................17 Blacksmiths and Calabash Carvers....................18 Woodcarving....................19 Textiles....................20 Religious Beliefs....................21, 23 Creation Myth....................22 Ifa Divination....................24, 25 Music and Dance....................26 Gelede Festivals and Egugun Ceremonies....................27 Yoruba Diaspora....................28 -

Copyright by Omaris Zunilda Zamora 2013

Copyright by Omaris Zunilda Zamora 2013 The Report Committee for Omaris Zunilda Zamora Certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: Let the Waters Flow: (Trans)locating Afro-Latina Feminist Thought APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Jossianna Arroyo Jennifer Wilks Let the Waters Flow: (Trans)locating Afro-Latina Feminist Thought by Omaris Zunilda Zamora, B.A. Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin December 2013 Dedication I dedicate this body of work to some of the most influential women in my life. Mom, you motivate me to be a warrior and to always keep up the good fight. To my sister, Omandra: I honestly, don’t know where my brain and my heart would be if you weren’t always there to remind me of who I am and where we are going. To my black sisters who are always sharing words of wisdom and dropping knowledge, continue being who you are. Acknowledgements I want to thank everyone who supported me every step of the way to make this work come to fruition. Professors Jossianna Arroyo, Jennifer Wilks, Luis Cárcamo-Huechante, and Cesar Salgado: thank you for your support and guidance in approaching this work, for sharing your perspective with me, and giving me the necessary feedback to continue re-thinking my project. I also want to take the time to thank my partner William García for his moral support in approaching life’s challenges and motivating me to keep going even when everything seemed physically impossible. -

AFN 121 Yoruba Tradition and Culture

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Open Educational Resources Borough of Manhattan Community College 2021 AFN 121 Yoruba Tradition and Culture Remi Alapo CUNY Borough of Manhattan Community College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/bm_oers/29 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Presented as part of the discussion on West Africa about the instructor’s Heritage in the AFN 121 course History of African Civilizations on April 20, 2021. Yoruba Tradition and Culture Prof. Remi Alapo Department of Ethnic and Race Studies Borough of Manhattan Community College [BMCC]. Questions / Comments: [email protected] AFN 121 - History of African Civilizations (Same as HIS 121) Description This course examines African "civilizations" from early antiquity to the decline of the West African Empire of Songhay. Through readings, lectures, discussions and videos, students will be introduced to the major themes and patterns that characterize the various African settlements, states, and empires of antiquity to the close of the seventeenth century. The course explores the wide range of social and cultural as well as technological and economic change in Africa, and interweaves African agricultural, social, political, cultural, technological, and economic history in relation to developments in the rest of the world, in addition to analyzing factors that influenced daily life such as the lens of ecology, food production, disease, social organization and relationships, culture and spiritual practice. -

Reglas De Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe) a Book by Lydia Cabrera an English Translation from the Spanish

THE KONGO RULE: THE PALO MONTE MAYOMBE WISDOM SOCIETY (REGLAS DE CONGO: PALO MONTE MAYOMBE) A BOOK BY LYDIA CABRERA AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION FROM THE SPANISH Donato Fhunsu A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature (Comparative Literature). Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Inger S. B. Brodey Todd Ramón Ochoa Marsha S. Collins Tanya L. Shields Madeline G. Levine © 2016 Donato Fhunsu ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Donato Fhunsu: The Kongo Rule: The Palo Monte Mayombe Wisdom Society (Reglas de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe) A Book by Lydia Cabrera An English Translation from the Spanish (Under the direction of Inger S. B. Brodey and Todd Ramón Ochoa) This dissertation is a critical analysis and annotated translation, from Spanish into English, of the book Reglas de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe, by the Cuban anthropologist, artist, and writer Lydia Cabrera (1899-1991). Cabrera’s text is a hybrid ethnographic book of religion, slave narratives (oral history), and folklore (songs, poetry) that she devoted to a group of Afro-Cubans known as “los Congos de Cuba,” descendants of the Africans who were brought to the Caribbean island of Cuba during the trans-Atlantic Ocean African slave trade from the former Kongo Kingdom, which occupied the present-day southwestern part of Congo-Kinshasa, Congo-Brazzaville, Cabinda, and northern Angola. The Kongo Kingdom had formal contact with Christianity through the Kingdom of Portugal as early as the 1490s. -

DIANA PATON & MAARIT FORDE, Editors

diana paton & maarit forde, editors ObeahThe Politics of Caribbean and Religion and Healing Other Powers Obeah and Other Powers The Politics of Caribbean Religion and Healing diana paton & maarit forde, editors duke university press durham & london 2012 ∫ 2012 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper $ Designed by Katy Clove Typeset in Arno Pro by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of Newcastle University, which provided funds toward the production of this book. Foreword erna brodber One afternoon when I was six and in standard 2, sitting quietly while the teacher, Mr. Grant, wrote our assignment on the blackboard, I heard a girl scream as if she were frightened. Mr. Grant must have heard it, too, for he turned as if to see whether that frightened scream had come from one of us, his charges. My classmates looked at me. Which wasn’t strange: I had a reputation for knowing the answer. They must have thought I would know about the scream. As it happened, all I could think about was how strange, just at the time when I needed it, the girl had screamed. I had been swimming through the clouds, unwillingly connected to a small party of adults who were purposefully going somewhere, a destination I sud- denly sensed meant danger for me. Naturally I didn’t want to go any further with them, but I didn’t know how to communicate this to adults and ones intent on doing me harm. -

Vodou and the U.S. Counterculture

VODOU AND THE U.S. COUNTERCULTURE Christian Remse A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2013 Committee: Maisha Wester, Advisor Katerina Ruedi Ray Graduate Faculty Representative Ellen Berry Tori Ekstrand Dalton Jones © 2013 Christian Remse All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Maisha Wester, Advisor Considering the function of Vodou as subversive force against political, economic, social, and cultural injustice throughout the history of Haiti as well as the frequent transcultural exchange between the island nation and the U.S., this project applies an interpretative approach in order to examine how the contextualization of Haiti’s folk religion in the three most widespread forms of American popular culture texts – film, music, and literature – has ideologically informed the U.S. counterculture and its rebellious struggle for change between the turbulent era of the mid-1950s and the early 1970s. This particular period of the twentieth century is not only crucial to study since it presents the continuing conflict between the dominant white heteronormative society and subjugated minority cultures but, more importantly, because the Enlightenment’s libertarian ideal of individual freedom finally encouraged non-conformists of diverse backgrounds such as gender, race, and sexuality to take a collective stance against oppression. At the same time, it is important to stress that the cultural production of these popular texts emerged from and within the conditions of American culture rather than the native context of Haiti. Hence, Vodou in these American popular texts is subject to cultural appropriation, a paradigm that is broadly defined as the use of cultural practices and objects by members of another culture. -

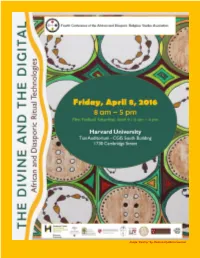

2016 Conference Program

Image “Destiny” by Deanna Oyafemi Lowman MOYO ~ BIENVENIDOS ~ E KAABO ~ AKWABAA BYENVENI ~ BEM VINDOS ~ WELCOME Welcome to the fourth conference of the African and Diasporic Religious Studies Association! ADRSA was conceived during a forum of scholars and scholar- practitioners of African and Diasporic religions held at the Center for the Study of World Religions at Harvard Divinity School in October 2011 and the idea was solidified during the highly successful Sacred Healing and Wholeness in Africa and the Americas symposium held at Harvard in April 2012. Those present at the forum and the symposium agreed that, as with the other fields with which many of us are affiliated, the expansion of the discipline would be aided by the formation of an association that allows researchers to come together to forge relationships, share their work, and contribute to the growing body of scholarship on these rich traditions. We are proud to be the first US-based association dedicated exclusively to the study of African and Diasporic Religions and we look forward to continuing to build our network throughout the country and the world. Although there has been definite improvement, Indigenous Religions of all varieties are still sorely underrepresented in the academic realms of Religious and Theological Studies. As a scholar- practitioner of such a tradition, I am eager to see that change. As of 2005, there were at least 400 million people practicing Indigenous Religions worldwide, making them the 5th most commonly practiced class of religions. Taken alone, practitioners of African and African Diasporic religions comprise the 8th largest religious grouping in the world, with approximately 100 million practitioners, and the number continues to grow. -

African Concepts of Energy and Their Manifestations Through Art

AFRICAN CONCEPTS OF ENERGY AND THEIR MANIFESTATIONS THROUGH ART A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Renée B. Waite August, 2016 Thesis written by Renée B. Waite B.A., Ohio University, 2012 M.A., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by ____________________________________________________ Fred Smith, Ph.D., Advisor ____________________________________________________ Michael Loderstedt, M.F.A., Interim Director, School of Art ____________________________________________________ John R. Crawford-Spinelli, D.Ed., Dean, College of the Arts TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………….. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS …………………………………… vi CHAPTERS I. Introduction ………………………………………………… 1 II. Terms and Art ……………………………………………... 4 III. Myths of Origin …………………………………………. 11 IV. Social Structure …………………………………………. 20 V. Divination Arts …………………………………………... 30 VI. Women as Vessels of Energy …………………………… 42 VII. Conclusion ……………………………………….…...... 56 VIII. Images ………………………………………………… 60 IX. Bibliography …………………………………………….. 84 X. Further Reading ………………………………………….. 86 iii LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: Porogun Quarter, Ijebu-Ode, Nigeria, 1992, Photograph by John Pemberton III http://africa.si.edu/exhibits/cosmos/models.html. ……………………………………… 60 Figure 2: Yoruba Ifa Divination Tapper (Iroke Ifa) Nigeria; Ivory. 12in, Baltimore Museum of Art http://www.artbma.org/. ……………………………………………… 61 Figure 3.; Yoruba Opon Ifa (Divination Tray), Nigerian; carved wood 3/4 x 12 7/8 x 16 in. Smith College Museum of Art, http://www.smith.edu/artmuseum/. ………………….. 62 Figure 4. Ifa Divination Vessel; Female Caryatid (Agere Ifa); Ivory, wood or coconut shell inlay. Nigeria, Guinea Coast The Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org. ……………………… 63 Figure 5. Beaded Crown of a Yoruba King. Nigerian; L.15 (crown), L.15 (fringe) in. -

On the Rationality of Traditional Akan Religion: Analyzing the Concept of God

Majeed, H. M/ Legon Journal of the Humanities 25 (2014) 127-141 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ljh.v25i1.7 On the Rationality of Traditional Akan Religion: Analyzing the Concept of God Hasskei M. Majeed Lecturer, Department of Philosophy and Classics, University of Ghana, Legon Abstract This paper is an attempt to show how logically acceptable (or rational) belief in Traditional Akan religion is. The attempt is necessitated by the tendency by some scholars to (mis) treat all religions in a generic sense; and the potential which Akan religion has to influence philosophical debates on the nature of God and the rationality of belief in God – generally, on the practice of religion. It executes this task by expounding some rational features of the religion and culture of the Akan people of Ghana. It examines, in particular, the concept of God in Akan religion. This paper is therefore a philosophical argument on the sacred and institutional representation of what humans have come to refer to as “religious.” Keywords: rationality; good; Akan religion; God; worship By “Traditional Akan religion,” I mean the indigenous system of sacred beliefs, values, and practices of the Akan people of Ghana1. This is not to say, however, that the Akans are only found in Ghana. Traditional Akan religion has features that distinguish it from other African religions, and more so from non-African ones. This seems to underscore the point that religious practice varies across the cultures of the world, although all religions could share some common attributes. Yet, some philosophers and religionists, for instance, have not been measured in their presentation of the general features of religion.