Alienation Reconsidered. Criticizing Non-Speculative Anti-Essentialism | Asger Sørensen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CRITICAL THEORY Past, Present, Future Anders Bartonek and Sven-Olov Wallensein (Eds.) SÖDERTÖRN PHILOSOPHICAL STUDIES

CRITICAL THEORY Past, Present, Future Anders Bartonek and Sven-Olov Wallensein (eds.) SÖDERTÖRN PHILOSOPHICAL STUDIES The series is attached to Philosophy at Sder- trn University. Published in the series are es- says as well as anthologies, with a particular em- phasis on the continental tradition, understood in its broadest sense, from German idealism to phenomenology, hermeneutics, critical theory and contemporary French philosophy. The com- mission of the series is to provide a platform for the promotion of timely and innovative phil- osophical research. Contributions to the series are published in English or Swedish. Cover image: Kristofer Nilson, System (Portrait of a Swedish Tax Form), 2020, Lead pencil drawing on chalk paint, on mdf 59.2 x 42 cm. Photo: Jesper Petersen. Te Swedish tax form is one of many systems designed to handle and present information. Mapped onto the surface of an artwork, it opens a free space; an untouched surface where everything can exist at the same time. Kristofer Nilson Critical Theory Past, Present, Future Edited by Anders Bartonek & Sven-Olov Wallenstein Sdertrns hgskola Sdertrns University Library SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications © the Authors Published under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License Cover layout: Jonathan Robson Graphic form: Per Lindblom & Jonathan Robson Printed by Elanders, Stockholm 2021 Sdertrn Philosophical Studies 28 ISSN 1651-6834 Sdertrn Academic Studies 83 ISSN 1650-433X ISBN 978-91-89109-35-3 (print) ISBN 978-91-89109-36-0 (digital) Contents Introduction -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Rahel Jaeggi [email protected] Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Center for Humanities and Social Change Unter den Linden 6 10099 Berlin I. AREAS OF SPECIALIZATION Social Philosophy, Political Philosophy, Ethics, Philosophical Anthropology, Social Ontology, Critical Theory, History of Critical Theory. II. EDUCATION 2009 Habilitation, Goethe University, Frankfurt a. M./Germany, on the subject of „Critique of Forms of Life“. 2002 PhD, Goethe University, Frankfurt a. M./Germany, with a dissertation on „Freedom and Indifference – A Reconstruction of the Concept of Alienation”. 1996 Magistra Artium (Master equivalent), Freie Universität Berlin with a thesis on Hannah Arendt's political philosophy. III. ACADEMIC POSITIONS Since February 2018 Director of the Center for Humanities and Social Change at the Humboldt-University of Berlin. 2016 Offer of the chair for Social Philosophy at the Goethe University Frankfurt a. M./Germany, declined. 2009–present Professor of Social Philosophy at the Humboldt University of Berlin/Germany. 2003–2009 Assistant Professor (Wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiterin, Postdoc) at the Institute for Philosophy, Goethe University Frankfurt a. M./Germany (Chair for Social Philosophy/Prof. Axel Honneth). 2001–2002 Research Assistant at the University of St. Gallen/Switzerland. 1996–2001 Research Associate (Wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiterin, Predoc) at the Institute for Philosophy, Goethe University Frankfurt a. M./Germany (Chair for Social Philosophy, Prof. Axel Honneth). 1989–1995 Studies of Philosophy, History and Theology at the Freie Universität Berlin. CV Rahel Jaeggi IV. FELLOWSHIPS AND INTERNATIONAL APPOINTMENTS 2018–2019 (Sept.–Apr.) Member at the Institute for Advanced Study, School for Social Science, Princeton/USA. 2015–2016 Theodor Heuss Professor at the New School for Social Research, New York/USA. -

Re-Thinking Ideology

Call for Papers: International Summer School Critical Theory 2018 (JULY 15 – JULY 20) RE-THINKING IDEOLOGY Why do people often accept, and even embrace, social and political conditions that seem to run counter to their own interests? How is it possible that we sometimes support forms of domination with our ways of behaving and thinking without intending or even realizing it? One answer to these questions refers to the notion of ideology. Ideologies are more or less coherent systems of practices and beliefs that shape how individuals relate to their social reality in ways that distort their understanding of what is wrong with that reality and thereby contribute to its reproduction. The summer school will seek to clarify the meanings and theoretical roles of ideology, as the concept has been prominently developed from the writings of Marx via Critical Theory in the tradition of the Frankfurt School to more recent debates in feminism and analytic philosophy. Key contemporary protagonists of ideology critique like Sally Haslanger, Robert Gooding-Williams, Axel Honneth, Alice Crary, Karen Ng, Titus Stahl, Robin Celikates, Martin Saar and Rahel Jaeggi will be present at the summer school and facilitate debates both of key texts from canonical authors and of their own systematic positions. We will discuss questions such as: What is ideology and in which sense are ideologies false or deficient? How do ideologies come into existence and how do they function? On which basis and from which standpoint can ideologies be criticized? What is the continuing -

Trivium , 32- Institutions Rahel Jaeggi – Notice 2

Trivium Revue franco-allemande de sciences humaines et sociales - Deutsch-französische Zeitschrift für Geistes- und Sozialwissenschaften 32- Institutions Rahel Jaeggi – notice Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/trivium/7352 ISSN: 1963-1820 Publisher Les éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’Homme Electronic reference « Rahel Jaeggi – notice », Trivium [En ligne], 32- Institutions, mis en ligne le 28 janvier 2021, consulté le 29 janvier 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/trivium/7352 This text was automatically generated on 29 January 2021. Les contenus des la revue Trivium sont mis à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Rahel Jaeggi – notice 1 Rahel Jaeggi – notice Trivium , 32- Institutions Rahel Jaeggi – notice 2 1 Rahel Jaeggi est, depuis 2009, professeur de philosophie pratique (spécialité : philosophie sociale) et directrice (depuis 2018) du Center for Humanities and Social Change à l’Université Humboldt de Berlin. Elle a fait des études de philosophie, d‘histoire et de théologie à l’Université Libre de Berlin puis à l’Université de Francfort- sur-le-Main, où elle a obtenu son doctorat en 2002 et son habilitation en 2009. Elle a été chercheuse (de 1996 à 2001) puis maître de conférences (2003-2009) à la chaire de philosophie sociale d’Axel Honneth à l’Université de Francfort-sur-le-Main et à l’Université de Saint-Gall (2001-2002). En tant que professeur invité, elle a enseigné à Yale, New Haven (2002-2003), à l’Université Fudan à Shanghai (sept.-oct. 2012) et à la New School for Social Research à New York (2015-2016). -

Downloads/Von Der Gesellschaftssteuerung Zur Sozialen Kontrolle.Pdf 704 the Conference Was Max Weber Und Die Soziologie Heute: Verhandlungen Des 15

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Political Deficits: The Dawn of Neoliberal Rationality and the Eclipse of Critical Theory Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9p0574bc Author Callison, William Andrew Publication Date 2019 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Political Deficits: The Dawn of Neoliberal Rationality and the Eclipse of Critical Theory By William Andrew Callison A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Wendy Brown, Chair Professor Pheng Cheah Professor Kinch Hoekstra Professor Martin Jay Professor Hans Sluga Professor Shannon C. Stimson Summer 2019 Political Deficits: The Dawn of Neoliberal Rationality and the Eclipse of Critical Theory Copyright © 2019 William Andrew Callison All rights reserved. Abstract Political Deficits: The Dawn of Neoliberal Rationality and the Eclipse of Critical Theory By William Andrew Callison Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Berkeley Professor Wendy Brown, Chair This dissertation examines the changing relationship between social science, economic governance, and political imagination over the past century. It specifically focuses on neoliberal, ordoliberal and neo-Marxist visions of politics and rationality from the interwar period to the recent Eurocrisis. Beginning with the Methodenstreit (or “methodological dispute”) between Gustav von Schmoller and Carl Menger and the subsequent “socialist calculation debate” about markets and planning, the dissertation charts the political and epistemological formation of the Austrian School (e.g., Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich A. -

The Concept of Critique in Critical Theory

Outhwaite W. Generations of Critical Theory? Berlin Journal of Critical Theory 2017, 1(1), 5-27. Copyright: ©2017. With permission granted from the publisher, this is the accepted manuscript of an article published by Berlin Journal of Critical Theory. weblink to article: http://www.bjct.de/home.html Date deposited: 25/08/2017 Newcastle University ePrints - eprint.ncl.ac.uk Generations of Critical Theory? This journal is oriented to re-evaluating early critical theory and is therefore an appropriate place to pose some questions about the periodisation of critical theory as a whole. Whether or not one accepts a generational model with Adorno, Horkheimer, Marcuse et al in the first generation, Habermas, Apel and Wellmer in the second and Honneth, Fraser and a cluster of other German and North American theorists in the third, a model powerfully criticised in relation to Habermas by Stefan Müller-Doohm (2017), there is general agreement that Habermas’s project has always been substantially diferent from that of the earlier critical theorists – themselves of course quite differentiated despite Horkheimer’s somewhat managerial attempts to present them as a team. But whereas Horkheimer’s earlier opposition to Habermas was based on anxiety that he was too radical and outspoken (Müller-Doohm 2016: 80-88), later commentators have polarised roughly between those who see Habermas’s project as a continuation of critical theory in a different mode more adapted to the realities of postwar advanced capitalist societies with their apparently stable liberal polities and those who see it as an abandonment of some of the more radical motifs of earlier critical theory. -

Fate of the Novel, Graduate Lecture, Spring 2011

1 SPRING 2016: GPHI5509 Professor Alice Crary The Case for Critique Office: 6 East 16th St., Rm. 1115A New School for Social Research [email protected] Th 2-3:50 pm, 6 E. 16th Street, Rm. 901 Off. hrs.: Th 4:00-6:00pm & by appt. Professor Rahel Jaeggi Office: 6 East 16th St., Rm. 1115 [email protected] Off. Hrs: Th 4:00-6:00pm & by appt. The Case for Critique: Syllabus Course description This course investigates the idea of immanent critique. We will consider forms of criticism that start from conceptual resources of actual or historical social practices, and we will take seriously the possibility that—although these forms of criticism lack the socially transcendent reach laid claim to by various familiar views that draw their main inspiration from Kant, and so might be said not to qualify as ‘external’—they are not merely ‘internal’ in a sense that would deprive them of genuine rational authority. The idea of immanent critique, thus understood, is sometimes rejected as no more than an illusion. Thinkers such as Hegel and Wittgenstein, who treat our normative positions as practice-bound, are often taken to be thereby depriving themselves of the requisite resources for a critical approach that is wholeheartedly rational. But both Hegel and Wittgenstein are plausibly read as insisting on a transformed image of rational critique is like—an image that straightforwardly combines an ineradicable link to practice with unqualified rational authority. Exploring this possibility and its consequences is the task of this seminar. Course readings will include classic and contemporary contributions to Critical Theory as well as contributions to Anglo- American analytic disputes about philosophy and the social sciences. -

Cv-Rahel-Jaeggi-English-1.Pdf

Curriculum vitae Prof. Dr. Rahel Jaeggi Humboldt University of Berlin Department of Philosophy Chair of Practical Philosophy and Social Philosophy Unter den Linden 6 10099 Berlin Areas of Specialization Social Philosophy, Political Philosophy, Ethics, Philosophical Anthropology, Social Ontology, Critical Theory, History of Critical Theory. Education 2009 Habilitation from the Goethe University, Frankfurt a. M./Germany, on the subject of "Critique of Forms of Life" 2002 Doctorate from the Goethe University, Frankfurt a. M./Germany, with a dissertation on "Freedom and Indifference – A reconstruction of the Concept of Alienation” 1996 Magistra Artium (Master equivalent) from the Free University of Berlin with a thesis on Hannah Arendt's political philosophy Academic Positions 2009–present Professor of Practical Philosophy with Emphasis on Social Philosophy and Political Philosophy at the Humboldt University of Berlin/Germany 2003–2009 Assistant Professor (Wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiterin, Postdoc) at the Institute for Philosophy, Goethe University, Frankfurt a. M./Germany (Chair for Social Philosophy/Prof. Axel Honneth) 1996–2001 Research Associate (Wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiterin, Predoc) at the Institute for Philosophy, Goethe University, Frankfurt a. M./Germany (Chair for Social Philosophy, Prof. Axel Honneth) Fellowships and international Appointments 2015–2016 Theodor Heuss Professor at the New School for Social Research, New York/USA. 2012 Visiting Professor at the Fudan University, Shanghai/PRC. 2012–2013 Senior Fellow at the DFG-Forschungskolleg ‚Postwachstumsgesellschaften‘, Friedrich Schiller University Jena/Germany. 2002–2003 Visiting Assistant Professor at the Yale University, New Haven/USA, Program for Ethics, Politics and Economics. 1999 Visiting Scholar at the New School for Social Research, New York/USA. Rahel Jaeggi – Curriculum vitae Publications I. -

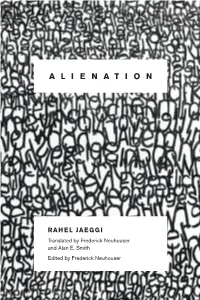

A L I E N a T I

ALIENATION RAHEL JAEGGI Translated by Frederick Neuhouser and Alan E. Smith Edited by Frederick Neuhouser ALIENATION new directions in critical theory C6471.indb i 6/3/14 8:38 AM new directions in critical theory Amy Allen, General Editor New Directions in Critical Theory presents outstanding classic and contem- porary texts in the tradition of critical social theory, broadly construed. The series aims to renew and advance the program of critical social theory, with a particular focus on theorizing contemporary struggles around gender, race, sexuality, class, and globalization and their complex interconnections. Narrating Evil: A Postmetaphysical Theory of Refl ective Judgment , María Pía Lara The Politics of Our Selves: Power, Autonomy, and Gender in Contemporary Critical Theory , Amy Allen Democracy and the Political Unconscious, Noëlle McAfee The Force of the Example: Explorations in the Paradigm of Judgment , Alessandro Ferrara Horrorism: Naming Contemporary Violence , Adriana Cavarero Scales of Justice: Reimagining Political Space in a Globalizing World , Nancy Fraser Pathologies of Reason: On the Legacy of Critical Theory , Axel Honneth States Without Nations: Citizenship for Mortals , Jacqueline Stevens The Racial Discourses of Life Philosophy: Négritude, Vitalism, and Modernity , Donna V. Jones Democracy in What State? Giorgio Agamben, Alain Badiou, Daniel Bensaïd, Wendy Brown, Jean-Luc Nancy, Jacques Rancière, Kristin Ross, Slavoj Žižek Politics of Culture and the Spirit of Critique: Dialogues , edited by Gabriel Rockhill and Alfredo -

Crary CV Web Version 6-20

Alice Crary Academic Positions University Distinguished Professor, Department of Philosophy (/Department of Liberal Studies/Gender and Sexuality Studies), New School for Social Research, 2019-. During Spring 2021, while teaching at the New School, I will hold a Visiting Professorship at the University of Paris-1 Pantheon Sorbonne. Professor of Philosophy, Tutorial Fellow in Philosophy and Christian Ethics, and Director of Studies for Philosophy, Regent’s Park College, University of Oxford, 2018-2019. Chair, Department of Philosophy, New School for Social Research, 2014-2017. Founding Co-director, Graduate Certificate in Gender and Sexuality Studies, New School, 2014- 2017. Visiting Professor, Department of Philosophy, Humboldt University, Berlin, Summer 2011. Assistant, Associate and Full Professor, Department of Philosophy, New School for Social Research, 2000-2017. Education PHD—University of Pittsburgh, December 1999. Dissertation “The Role of Feeling in Moral Thought,” directed by John McDowell. AB in Philosophy—Harvard College, June 1990. Summa cum laude for honors thesis “‘I Know I’m in Pain’: An Essay on the Philosophy of Wittgenstein,” directed by Hilary Putnam (Bechtel Prize for Best Undergraduate or Graduate Essay in Philosophy). Areas of Research Moral Philosophy; Social Philosophy, including Critical Theory, Critical Disability Studies and Critical Race Theory; Critical Animal Studies; Aesthetics, especially Philosophy and Literature; Wittgenstein/Austin/Speech Act Theory; Feminism and Philosophy. Crary 2 of 30 Honors and Fellowships Visiting Fellow, Regent’s Park College, Oxford, 2020-present. Honorary Guest Wittgenstein Professor, University of Innsbruck, Austria, Summer 2018. Member, School of Social Studies, Institute for Advanced Studies, Princeton, NJ, School of Social Studies, 2017-2018. Fellow, Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics, 2016-present. -

Kriterion Miolo 110.P65 3/1/2005, 09:47294 PROLEGOMENON for an ETHICS of VISIBILITY in HANNAH ARENDT 295

PROLEGOMENON FOR AN ETHICS OF VISIBILITY IN HANNAH ARENDT* Bethânia Assy** ABSTRACT This paper aims to discuss the Arendtian notions of appearance and perception in order to promote a displacement of those conceptions from the generally associated domain of passive apprehension of the faculty of knowledge towards the domain of a praxiology of action and language, based on an active perception. Arendt’s appropriations on the Heideggerian “to take one’s <it> place” (sich hin-stellen) will be discussed, as well as the Augustinian “finding oneself in the world” (diligere). A twofold disposition of appearance will be distinguished: producing and position, whose transposed to the Arendtian notion of world correspond, respectively, to fabrication (poiesis) of the world, man’s objective in-between space, and to action (praxis) in the world, man’s subjective in-between space. Those conceptual replacements, in a broad sense, uphold a closer imbrication between the activities of the mind and acting, stricto sensu, and consequently, foment not only the valorization of the public space, but the visibility of our acts and deeds as well, calling out the dignity of appearance in ethics. Key-words Ethics of visibility, Hannah Arendt, Martin Heidegger, Active Perception, Appearance * Paper delivered at Prof. Axel Honneth’s Forschungskolloquium zur Sozialphilosophie in the Philosophy Department at Frankfurt University during my stay as visiting scholar in the Summer Semester/2003. An the same occasion this paper was also delivered at Kolloquium des Hannah Arendt-Zentrums, at the Carl Von Ossietzky University, Oldenburg, directed by Antonia Grunenberg. I am particularly in debt to the comments of Antonia Grunenberg, Hans Scheulen, Zoltan Szankay, Francisco Ortega, Axel Honneth, Rainer Forst and Rahel Jaeggi. -

Critical Theory

Nordic Wittgenstein Review 7 (1) 2018 | pp. 7-41 | DOI 10.15845/nwr.v7i1.3493 INVITED PAPER Alice Crary alicecrary @ yahoo.com Wittgenstein Goes to Frankfurt (and Finds Something Useful to Say) Abstract This article aims to shed light on some core challenges of liberating social criticism. Its centerpiece is an intuitively attractive account of the nature and difficulty of critical social thought that nevertheless goes missing in many philosophical conversations about such thought. This omission at bottom reflects the fact that the account presupposes a philosophically contentious conception of rationality. Yet the relevant conception of rationality does in fact inform influential philosophical treatments of social criticism, including, very prominently, a left Hegelian strand of thinking within contemporary Critical Theory. Moreover, it is possible to mount a defense of the conception by reconstructing, if with various qualifications and additions, an argument from classic – mid twentieth-century – Anglo-American philosophy of the social sciences, in particular, the argument that forms the backbone of Peter Winch’s The Idea of a Social Science. Winch draws his guiding insights from the later philosophy of Wittgenstein, and one of the payoffs of considering Winch’s Wittgenstein-inspired work against the backdrop of Hegel-inspired work in Critical Theory is to contest the artificial professional strictures that are sometimes taken to speak against reaching across the so-called ‘Continental Divide’ in philosophy. The larger payoff is advancing, by means of this philosophically ecumenical approach, the enterprise of liberating social thought. 1. The Idea of Widely Rational Critique It is plausible but by no means uncontroversial to suggest that liberating social criticism needs to be conceived so that it is capable 7 Alice Crary CC-BY of harnessing the cognitive power of critical gestures that shape our sense of what is important, inviting us to see social phenomena in new moral and political lights.