Biodiversity Hotspots in India 1. Himalaya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Development Or Despoilation? - Krishnakumar

Andaman Islands: Development or Despoilation? - Krishnakumar DEVELOPMENT OR DESPOILATION? The Andaman Islands under colonial and postcolonial regimes M.V. KRISHNAKUMAR Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi <[email protected]> Abstract The last quarter of the 19th Century marked an important watershed in the history of the Andaman Islands. The establishment of a penal settlement and an Imperial forestry service, along with other radical changes in the islands’ traditional economy and society, completely transformed the basic pattern of their forest resource use and entire system of forest management. These colonial policies, directly or indirectly, had a drastic impact on the indigenous population and island ecology. This article analyses the sources of environmental change in the Andaman Islands by examining the general ecological impacts of the state initiated development programmes. It also analyses the ‘civilising missions’ and forestry operations undertaken by British colonial administrators as well as the Indian state’s development initiatives under the ‘Five Year Plans’ that followed Indian independence in 1947. Keywords Andaman Islands, forestry, development, environmental change, Andaman tribes Introduction On December 26th 2004 a tsunami triggered by an earthquake off the south east coast of Sumatra swept across the Indian Ocean swamping many low-lying coastal areas and causing death, destruction of properties and infrastructure and despoliation of crops. Amongst those territories worst affected by the surge were the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. When Indian prime minister Dr Manmohan Singh visited the islands in the immediate aftermath of the flooding he identified that the project to reconstruct and rehabilitate coastal areas of islands provided the opportunity for a ‘New Andamans’ in which sustainable agriculture and fishery enterprises could exist in harmony with the natural environment. -

The Andaman Islands Penal Colony: Race, Class, Criminality, and the British Empire*

IRSH 63 (2018), Special Issue, pp. 25–43 doi:10.1017/S0020859018000202 © 2018 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The Andaman Islands Penal Colony: Race, Class, Criminality, and the British Empire* C LARE A NDERSON School of History, Politics and International Relations University of Leicester University Road, Leicester LE1 7RH, UK E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: This article explores the British Empire’s configuration of imprisonment and transportation in the Andaman Islands penal colony. It shows that British governance in the Islands produced new modes of carcerality and coerced migration in which the relocation of convicts, prisoners, and criminal tribes underpinned imperial attempts at political dominance and economic development. The article focuses on the penal transportation of Eurasian convicts, the employment of free Eurasians and Anglo-Indians as convict overseers and administrators, the migration of “volunteer” Indian prisoners from the mainland, the free settlement of Anglo-Indians, and the forced resettlement of the Bhantu “criminal tribe”.It examines the issue from the periphery of British India, thus showing that class, race, and criminality combined to produce penal and social outcomes that were different from those of the imperial mainland. These were related to ideologies of imperial governmentality, including social discipline and penal practice, and the exigencies of political economy. INTRODUCTION Between 1858 and 1939, the British government of India transported around 83,000 Indian and Burmese convicts to the penal colony of the Andamans, an island archipelago situated in the Bay of Bengal (Figure 1). -

Arachnozoogeographical Analysis of the Boundary Between Eastern Palearctic and Indomalayan Region

Historia naturalis bulgarica, 23: 5-36, 2016 Arachnozoogeographical analysis of the boundary between Eastern Palearctic and Indomalayan Region Petar Beron Abstract: This study aims to test how the distribution of various orders of Arachnida follows the classical subdivision of Asia and where the transitional zone between the Eastern Palearctic (Holarctic Kingdom) and the Indomalayan Region (Paleotropic) is situated. This boundary includes Thar Desert, Karakorum, Himalaya, a band in Central China, the line north of Taiwan and the Ryukyu Islands. The conclusion is that most families of Arachnida (90), excluding most of the representatives of Acari, are common for the Palearctic and Indomalayan Regions. There are no endemic orders or suborders in any of them. Regarding Arach- nida, their distribution does not justify the sharp difference between the two Kingdoms (Paleotropical and Holarctic) in Eastern Eurasia. The transitional zone (Sino-Japanese Realm) of Holt et al. (2013) also does not satisfy the criteria for outlining an area on the same footing as the Palearctic and Indomalayan Realms. Key words: Palearctic, Indomalayan, Arachnozoogeography, Arachnida According to the classical subdivision the region’s high mountains and plateaus. In southern Indomalayan Region is formed from the regions in Asia the boundary of the Palearctic is largely alti- Asia that are south of the Himalaya, and a zone in tudinal. The foothills of the Himalaya with average China. North of this “line” is the Palearctic (consist- altitude between about 2000 – 2500 m a.s.l. form the ing og different subregions). This “line” (transitional boundary between the Palearctic and Indomalaya zone) is separating two kingdoms, therefore the dif- Ecoregions. -

Understanding REPORT of the WESTERNGHATS ECOLOGY EXPERT PANEL

Understanding REPORT OF THE WESTERNGHATS ECOLOGY EXPERT PANEL KERALA PERSPECTIVE KERALA STATE BIODIVERSITY BOARD Preface The Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel report and subsequent heritage tag accorded by UNESCO has brought cheers to environmental NGOs and local communities while creating apprehensions among some others. The Kerala State Biodiversity Board has taken an initiative to translate the report to a Kerala perspective so that the stakeholders are rightly informed. We need to realise that the whole ecosystem from Agasthyamala in the South to Parambikulam in the North along the Western Ghats in Kerala needs to be protected. The Western Ghats is a continuous entity and therefore all the 6 states should adopt a holistic approach to its preservation. The attempt by KSBB is in that direction so that the people of Kerala along with the political decision makers are sensitized to the need of Western Ghats protection for the survival of themselves. The Kerala-centric report now available in the website of KSBB is expected to evolve consensus of people from all walks of life towards environmental conservation and Green planning. Dr. Oommen V. Oommen (Chairman, KSBB) EDITORIAL Western Ghats is considered to be one of the eight hottest hot spots of biodiversity in the World and an ecologically sensitive area. The vegetation has reached its highest diversity towards the southern tip in Kerala with its high statured, rich tropical rain fores ts. But several factors have led to the disturbance of this delicate ecosystem and this has necessitated conservation of the Ghats and sustainable use of its resources. With this objective Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel was constituted by the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) comprising of 14 members and chaired by Prof. -

Shiva's Waterfront Temples

Shiva’s Waterfront Temples: Reimagining the Sacred Architecture of India’s Deccan Region Subhashini Kaligotla Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 © 2015 Subhashini Kaligotla All rights reserved ABSTRACT Shiva’s Waterfront Temples: Reimagining the Sacred Architecture of India’s Deccan Region Subhashini Kaligotla This dissertation examines Deccan India’s earliest surviving stone constructions, which were founded during the 6th through the 8th centuries and are known for their unparalleled formal eclecticism. Whereas past scholarship explains their heterogeneous formal character as an organic outcome of the Deccan’s “borderland” location between north India and south India, my study challenges the very conceptualization of the Deccan temple within a binary taxonomy that recognizes only northern and southern temple types. Rejecting the passivity implied by the borderland metaphor, I emphasize the role of human agents—particularly architects and makers—in establishing a dialectic between the north Indian and the south Indian architectural systems in the Deccan’s built worlds and built spaces. Secondly, by adopting the Deccan temple cluster as an analytical category in its own right, the present work contributes to the still developing field of landscape studies of the premodern Deccan. I read traditional art-historical evidence—the built environment, sculpture, and stone and copperplate inscriptions—alongside discursive treatments of landscape cultures and phenomenological and experiential perspectives. As a result, I am able to present hitherto unexamined aspects of the cluster’s spatial arrangement: the interrelationships between structures and the ways those relationships influence ritual and processional movements, as well as the symbolic, locative, and organizing role played by water bodies. -

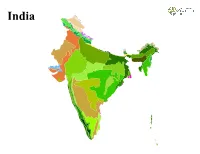

R Graphics Output

India India LEGEND Ecoregion Andaman Islands rain forests Mizoram−Manipur−Kachin rain forests Aravalli west thorn scrub forests Narmada Valley dry deciduous forests Baluchistan xeric woodlands Nicobar Islands rain forests Brahmaputra Valley semi−evergreen forests North Deccan dry deciduous forests Central Deccan Plateau dry deciduous forests North Western Ghats moist deciduous forests Central Tibetan Plateau alpine steppe North Western Ghats montane rain forests Chhota−Nagpur dry deciduous forests Northeast Himalayan subalpine conifer forests Chin Hills−Arakan Yoma montane forests Northeast India−Myanmar pine forests Deccan thorn scrub forests Northern Triangle temperate forests East Deccan dry−evergreen forests Northwestern Himalayan alpine shrub and meadows East Deccan moist deciduous forests Orissa semi−evergreen forests Eastern Himalayan alpine shrub and meadows Rann of Kutch seasonal salt marsh Eastern Himalayan broadleaf forests Rock and Ice Eastern Himalayan subalpine conifer forests South Deccan Plateau dry deciduous forests Godavari−Krishna mangroves South Western Ghats moist deciduous forests Himalayan subtropical broadleaf forests South Western Ghats montane rain forests Himalayan subtropical pine forests Sundarbans freshwater swamp forests Indus River Delta−Arabian Sea mangroves Sundarbans mangroves Karakoram−West Tibetan Plateau alpine steppe Terai−Duar savanna and grasslands Khathiar−Gir dry deciduous forests Thar desert Lower Gangetic Plains moist deciduous forests Upper Gangetic Plains moist deciduous forests Malabar Coast moist forests Western Himalayan alpine shrub and meadows Maldives−Lakshadweep−Chagos Archipelago tropical moist forests Western Himalayan broadleaf forests Meghalaya subtropical forests Western Himalayan subalpine conifer forests. -

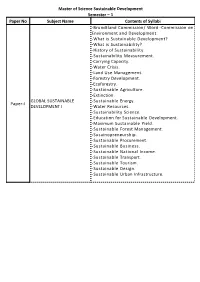

Master of Science Sustainable Development Semester – 1 Paper

Master of Science Sustainable Development Semester – 1 Paper No Subject Name Contents of Syllabi -Brundtland Commission/ Word -Commission on Environment and Development. -What is Sustainable Development? -What is Sustainability? -History of Sustainability. -Sustainability Measurement. -Carrying Capacity. -Water Crisis. -Land Use Management. -Forestry Development. -Ecoforestry. -Sustainable Agriculture. -Extinction. GLOBAL SUSTAINABLE -Sustainable Energy. Paper-I DEVELOPMENT I -Water Resources. -Sustainability Science. -Education for Sustainable Development. -Maximum Sustainable Yield. -Sustainable Forest Management. -Susainopreneurship. -Sustainable Procurement. -Sustainable Business. -Sustainable National Income. -Sustainable Transport. -Sustainable Tourism. -Sustainable Design. -Sustainable Urban Infrastructure. Master of Science Sustainable Development -What is Biodiversity? -Measurement of Biodiversity. -Species Richness. -Shannon Index. -2010 Biodiversity Indicators- Partnership. -Evolution. -Evolutionary Thought. -How does Evolution Occur? -Timeline of Evolution. BIODIVERSITY -Social Effect of Evolutionary Theory. Paper-II CONSERVATION & -Objections of Evolution. MANAGEMENT I -Population Genetics. -Genetics. -Heredity. -Mutation. -Molecular Evolution. -Genetic Recombination. -Sexual Reproduction. -Gene Flow. -Hybrid. -What is Energy? -History of Energy. -Timeline of Thermodynamics. -Units of Energy. -Potential Energy. -Elastic Energy. -Kinetic Energy. -Internal Energy. -Electromagnetism. -Electricity. GLOBAL ENERGY POLICIES Paper-III -

Adopt a Heritage Project - List of Adarsh Monuments

Adopt a Heritage Project - List of Adarsh Monuments Monument Mitras are invited under the Adopt a Heritage project for selecting/opting monuments from the below list of Adarsh Monuments under the protection of Archaeological Survey of India. As provided under the Adopta Heritage guidelines, a prospective Monument Mitra needs to opt for monuments under a package. i.e Green monument has to be accompanied with a monument from the Blue or Orange Category. For further details please refer to project guidelines at https://www.adoptaheritage.in/pdf/adopt-a-Heritage-Project-Guidelines.pdf Please put forth your EoI (Expression of Interest) for selected sites, as prescribed in the format available for download on the Adopt a Heritage website: https://adoptaheritage.in/ Sl.No Name of Monument Image Historical Information Category The Veerabhadra temple is in Lepakshi in the Anantapur district of the Indian state of Andhra Virabhadra Temple, Pradesh. Built in the 16th century, the architectural Lepakshi Dist. features of the temple are in the Vijayanagara style 1 Orange Anantpur, Andhra with profusion of carvings and paintings at almost Pradesh every exposed surface of the temple. It is one of the centrally protected monumemts of national importance. 1 | Page Nagarjunakonda is a historical town, now an island located near Nagarjuna Sagar in Guntur district of Nagarjunakonda, 2 the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, near the state Orange Andhra Pradesh border with Telangana. It is 160 km west of another important historic site Amaravati Stupa. Salihundam, a historically important Buddhist Bhuddist Remains, monument and a major tourist attraction is a village 3 Salihundum, Andhra lying on top of the hill on the south bank of the Orange Pradesh Vamsadhara River. -

Southern India Project Elephant Evaluation Report

SOUTHERN INDIA PROJECT ELEPHANT EVALUATION REPORT Mr. Arin Ghosh and Dr. N. Baskaran Technical Inputs: Dr. R. Sukumar Asian Nature Conservation Foundation INNOVATION CENTRE, INDIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE, BANGALORE 560012, INDIA 27 AUGUST 2007 CONTENTS Page No. CHAPTER I - PROJECT ELEPHANT GENERAL - SOUTHERN INDIA -------------------------------------01 CHAPTER II - PROJECT ELEPHANT KARNATAKA -------------------------------------------------------06 CHAPTER III - PROJECT ELEPHANT KERALA -------------------------------------------------------15 CHAPTER IV - PROJECT ELEPHANT TAMIL NADU -------------------------------------------------------24 CHAPTER V - OVERALL CONCLUSIONS & OBSERVATIONS -------------------------------------------------------32 CHAPTER - I PROJECT ELEPHANT GENERAL - SOUTHERN INDIA A. Objectives of the scheme: Project Elephant was launched in February 1992 with the following major objectives: 1. To ensure long-term survival of the identified large elephant populations; the first phase target, to protect habitats and existing ranges. 2. Link up fragmented portions of the habitat by establishing corridors or protecting existing corridors under threat. 3. Improve habitat quality through ecosystem restoration and range protection and 4. Attend to socio-economic problems of the fringe populations including animal-human conflicts. Eleven viable elephant habitats (now designated Project Elephant Ranges) were identified across the country. The estimated wild population of elephants is 30,000+ in the country, of which a significant -

Bird Diversity of Protected Areas in the Munnar Hills, Kerala, India

PRAVEEN & NAMEER: Munnar Hills, Kerala 1 Bird diversity of protected areas in the Munnar Hills, Kerala, India Praveen J. & Nameer P. O. Praveen J., & Nameer P.O., 2015. Bird diversity of protected areas in the Munnar Hills, Kerala, India. Indian BIRDS 10 (1): 1–12. Praveen J., B303, Shriram Spurthi, ITPL Main Road, Brookefields, Bengaluru 560037, Karnataka, India. Email: [email protected] Nameer P. O., Centre for Wildlife Studies, College of Forestry, Kerala Agricultural University, KAU (PO), Thrissur 680656, Kerala, India. India. [email protected] Introduction Table 1. Protected Areas (PA) of Munnar Hills The Western Ghats, one of the biodiversity hotspots of the Protected Area Abbreviation Area Year of world, is a 1,600 km long chain of mountain ranges running (in sq.km.) formation parallel to the western coast of the Indian peninsula. The region Anamudi Shola NP ASNP 7.5 2003 is rich in endemic fauna, including birds, and has been of great biogeographical interest. Birds have been monitored regularly Eravikulam NP ENP 97 1975 in the Western Ghats of Kerala since 1991, with more than 60 Kurinjimala WLS KWLS 32 2006 surveys having been carried out in the entire region (Praveen & Pampadum Shola NP PSNP 11.753 2003 Nameer 2009). This paper is a result of such a survey conducted in December 2012 supplemented by relevant prior work in this area. Anamalais sub-cluster in southern Western Ghats (Nair 1991; Das Munnar Hills (10.083°–10.333°N, 77.000°–77.617°E), et al. 2006). Anamudi (2685 m), the highest peak in peninsular forming part of the High Ranges of Western Ghats, also known as India, lies in these hills inside Eravikulam National Park (NP). -

P. Sujanapal Kerala Forest Research Institute India Western Ghats – the Lifeline of Peninsular India Phytogeographical Similarities with Sri Lanka

MANAGEMENT OF INVASIVE ALIEN PLANTS IN THE MOIST DECIDUOUS FORESTS OF WESTERN GHATS, INDIA P. Sujanapal Kerala Forest Research Institute India Western Ghats – The lifeline of Peninsular India Phytogeographical similarities with Sri Lanka - Northern WG - Central WG - Southern WG Southern Western Ghats Palakkad Gap Nilgiri-Wyanad-Kodagu Anamalai Hills – The heart of SWG Palani Hills Agasthyamalai Hills The landscape – DEM Anamalai Phytogeographical region, WG Topography & Vegetation Nelliyampathy Hills Pandaravarai Pezha mala Chalakkudy Forest Division Reservoir Parambikulam Tiger Reserve Vengoli Reservoir Karimala gopuram Vazhachal Forest Division Reservoir FOREST HEALTH vs INTRODUCTION & SPREAD OF IAS - INVERSELY PROPORTIONAL MDF - Major habitat/forest type in the windward region of Western Ghats Moist Deciduous Forest – Hot spot of IAS Compared to other habitats (evergreen, semi-evergreen and shola forests) highly susceptible to introduction and spread of IAS Seasonal variation in the canopy – Leaves sheds during summer, it paved way for the introduction Center of major timber yielding trees and commercially important species Dense feeding ground of herbivores , thus carnivores - an ideal habitat Most of the agricultural landscapes in the lowlands are midlands bordered by MDF – landscape sharing Human wildlife conflict is more reported in this type of landscape Deterioration in the quality of the ecosystem, directly affects the adjacent agricultural system, increases the human- wildlife conflict, etc. Since protection of the reserve forests -

The Sunda Shelf the Continent, People Were Forced to Flee in All Discover Island Sanctuaries from the Directions

Seen&HeArd lying over the Anambas Islands is a lovely sight. Island after island dots the sea with azure blue reefs blending into rainforest mountain peaks. Only 24 of these 238 islands Fare inhabited – a hidden world amidst the bustling South China Sea. I contemplate the spectacular scenery from the window flying overhead and realise that only the mountain tops are peaking up through the waters edge and recall reading about the drowned continent of Southeast Asia called Sundaland. This ancient land of Asia became the South China Sea about 8,000 years ago when the ocean water rose at the end of the last ice age. Once fertile valleys and To The Heights Of lowlands now lie submerged, forests turned into reefs, lagoons and a rolling continental shelf. During these years, as the ocean claimed The Sunda Shelf the continent, people were forced to flee in all Discover island sanctuaries from the directions. Those who lived near mountains would lost continent of Sundaland. have moved upwards, but those living in the valleys By Abigail Alling, President PCRF and far from the mountains were flooded. Thus, these people gathered themselves and became sea nomads, adrift in search of higher land. Many colourful, bustling city with ample supplies and think that these “sea-people” from this ancient gentle, friendly people. Just around the corner, civilization spread north to the Asian continent, on the waters edge in a sheltered bay, is a hotel south to Australia, west to Africa and the Middle located at Tanjung Tebu. There you will find excellent East, and east to Polynesia.