A Project of Five Canadian Academic Libraries Tony Horava University of Ottawa, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average Price by Percentage Increase: January to June 2016

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average price by percentage increase: January to June 2016 C06 – $1,282,135 C14 – $2,018,060 1,624,017 C15 698,807 $1,649,510 972,204 869,656 754,043 630,542 672,659 1,968,769 1,821,777 781,811 816,344 3,412,579 763,874 $691,205 668,229 1,758,205 $1,698,897 812,608 *C02 $2,122,558 1,229,047 $890,879 1,149,451 1,408,198 *C01 1,085,243 1,262,133 1,116,339 $1,423,843 E06 788,941 803,251 Less than 10% 10% - 19.9% 20% & Above * 1,716,792 * 2,869,584 * 1,775,091 *W01 13.0% *C01 17.9% E01 12.9% W02 13.1% *C02 15.2% E02 20.0% W03 18.7% C03 13.6% E03 15.2% W04 19.9% C04 13.8% E04 13.5% W05 18.3% C06 26.9% E05 18.7% W06 11.1% C07 29.2% E06 8.9% W07 18.0% *C08 29.2% E07 10.4% W08 10.9% *C09 11.4% E08 7.7% W09 6.1% *C10 25.9% E09 16.2% W10 18.2% *C11 7.9% E10 20.1% C12 18.2% E11 12.4% C13 36.4% C14 26.4% C15 31.8% Compared to January to June 2015 Source: RE/MAX Hallmark, Toronto Real Estate Board Market Watch *Districts that recorded less than 100 sales were discounted to prevent the reporting of statistical anomalies R City of Toronto — Neighbourhoods by TREB District WEST W01 High Park, South Parkdale, Swansea, Roncesvalles Village W02 Bloor West Village, Baby Point, The Junction, High Park North W05 W03 Keelesdale, Eglinton West, Rockcliffe-Smythe, Weston-Pellam Park, Corso Italia W10 W04 York, Glen Park, Amesbury (Brookhaven), Pelmo Park – Humberlea, Weston, Fairbank (Briar Hill-Belgravia), Maple Leaf, Mount Dennis W05 Downsview, Humber Summit, Humbermede (Emery), Jane and Finch W09 W04 (Black Creek/Glenfield-Jane -

HISTORICAL WALKING TOUR of Deer Park Joan C

HISTORICAL WALKING TOUR OF Deer Park Joan C. Kinsella Ye Merrie Circle, at Reservoir Park, c.1875 T~ Toronto Public Library Published with the assistance of Marathon Realty Company Limited, Building Group. ~THON --- © Copyright 1996 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Toronto Public Library Board Kinsella. Joan c. (Joan Claire) 281 Front Street East, Historical walking tour of Deer Park Toronto, Ontario Includes bibliographical references. M5A412 ISBN 0-920601-26-X Designed by: Derek Chung Tiam Fook 1. Deer Park (Toronto, OnL) - Guidebooks. 2. Walking - Ontario - Toronto - Guidebooks Printed and bound in Canada by: 3. Historic Buildings - Ontario - Toronto - Guidebooks Hignell Printing Limited, Winnipeg, Manitoba 4. Toronto (Ont.) - Buildings, structures, etc - Guidebooks. 5. Toronto (OnL) - Guidebooks. Cover Illustrations I. Toronto Public Ubrary Board. II. TItle. Rosehill Reservoir Park, 189-? FC3097.52.K56 1996 917.13'541 C96-9317476 Stereo by Underwood & Underwood, FI059.5.T68D45 1996 Published by Strohmeyer & Wyman MTL Tll753 St.Clair Avenue, looking east to Inglewood Drive, showing the new bridge under construction and the 1890 iron bridge, November 3, 1924 CTA Salmon 1924 Pictures - Codes AGO Art Gallery of Ontario AO Archives of Ontario CTA City of Toronto Archives DPSA Deer Park School Archives JCK Joan C. Kinsella MTL Metropolitan Toronto Library NAC National Archives of Canada TPLA Toronto Public Library Archives TTCA Toronto Transit Commission Archives ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Woodlawn. Brother Michael O'Reilly, ES.C. and Brother Donald Morgan ES.C. of De La This is the fifth booklet in the Toronto Public Salle College "Oaklands" were most helpful library Board's series of historical walking in providing information. -

LPRO E-Newsletter Feb 15 2021

E-Newsletter 15 February 2021 http://www.lyttonparkro.ca/ The Lytton Park Residents’ Organization (LPRO) is an incorporated non-profit association, representing member households from Lawrence Avenue West to Roselawn and Briar Hill Avenues, Yonge Street to Saguenay and Proudfoot Avenue. We care about protecting and advancing the community’s interests and fostering a sense of neighbourhood in our area. We work together to make our community stronger, sharing information about our community issues and events. “Together we do make a difference!” Keeping Our Community Connected: Follow us on Twitter! Our Twitter handle is @LyttonParkRO LPRO’s Community E-Newsletter - It’s FREE! If you do not already receive the LPRO’s E-Newsletter and would like to receive it directly, please register your email address at www.lyttonparkro.ca/newsletter-sign-up or send us an email to [email protected]. Please share this newsletter with neighbours! Check out LPRO’s New Website! Click HERE Community Residents’ Association Membership - Renew or Join for 2021 As a non-profit organization run by community volunteers, we rely on your membership to cover our costs to advocate for the community, provide newsletters, lead an annual community yard sale and a ravine clean-up, organize speaker events and host election candidate debates. Please join or renew your annual membership. The membership form and details on how to pay the $30 annual fee are on the last page of this newsletter or on our website at http://www.lyttonparkro.ca/ . If you are a Member you will automatically get LPRO’s Newsletters. Thank you for your support! Have a Happy Family Day! LPRO E-Newsletter – 15 February 2021 1 Settlement Achieved - 2908 Yonge Development at Chatsworth A lot has happened in a very short space of time, including a settlement which approves the zoning for a building at 2908 Yonge (the former Petrocan site at Chatsworth and Yonge). -

Community Information

Community Information MEN 23959 Broker Demographic Brochure V9.indd 1 2014-07-29 4:56 PM th Yonge & Eglinton ranked 4 out of 140 Toronto neighbourhoods. “Best Places To Live in the City” Toronto Life Magazine 2013 survey The Yonge & Eglinton Neighbourhood The Eglinton truly is Yonge at heart. Located on Eglinton Avenue in the prime midtown area known as Yonge and Eglinton, this elegant new condominium proudly takes up residence in one of the city’s most desirable neighbourhoods. Not only is the area one of the best places to live in the city, it is fast becoming a major economic hub in the city. From an employment standpoint, it is ranked as the second largest and fastest growing employment centre in Toronto. The Eglinton at a glance Bathurst St. St. Yonge Mt. Pleasant Rd. Lawrence Ave. Bayview Ave. Developer: Menkes Developments Location: Yonge & Eglinton Architect: Giannone Petriconne Associates Eglinton Ave. Yonge + Central. Interior Designers: Mike Niven Interior Design THE EGLINTON Landscape Designers: NAK Design Group St. Clair Ave. Statistics: 34 storeys Amenities: Lobby with 24-hr concierge Fitness centre Party room with catering kitchen and bar Wireless lounge Party room Outdoor terrace with BBQ, dining area, lounge and sundeck Kids room 2 guest suites 3 LIFE STOREYS menkes.com MEN 23959 Broker Demographic Brochure V9.indd 2-3 2014-07-29 4:56 PM HWY 401 WILSON AVE. YORK MILLS RD. LAWRENCE AVE. W. LAWRENCE AVE. E. Locke Library Havergal College Lawrence Park Osler Bluff Ski Club Yonge Street Animal Hospital Assaggio menkes.com Blythwood Ravine Park Lytton Park LYTTON BLVD. -

Document.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS Cadillac Fairview and YCC Introduction 2 YCC Building Hours 3 Cadillac Fairview Meet the Team 4 Security and Life Safety 5 Janitorial 7 Green Initiatives 7 Parking and Transportation 8 Available Services 10 Corporate Concierge Service 11 Amenities at YCC 12 Amenities in the Neighborhood 13 Restaurants 14 Emergency Preparedness 15 General Information, Fire Wardens/Deputy Wardens 16 Fire Alarm 18 Bomb Threat Procedures 20 Medical Emergencies 22 Elevator Malfunction/Entrapment 23 2 WELCOME TO YONGE CORPORATE CENTRE On behalf of Cadillac Fairview Corporation we are pleased to welcome you to Yonge Corporate Centre. YCC is one of North Toronto’s premier office towers whose employees are dedicated to your total satisfaction. We have prepared this guide to answer many of the most commonly asked questions regarding building operations, systems and the numerous amenities in and around YCC. We strongly encourage you and your staff to familiarize yourself with the services and operations of YCC and we hope you find this helpful and informative. Please retain this manual for future reference as it will be amended and updated time to time. Studies show that more than half of all adult waking hours are spent in work related activities. YCC is designed to be a pleasant and productive business home during these hours by providing a quality and efficient working environment for business’s and its employees. We are proud you have chosen the Yonge Corporate Centre and look forward to a long and mutually beneficial relationship. We welcome your comments and encourage you to discuss with us any suggestions as to how we may improve our services: The Cadillac Fairview Corporation Limited 4100 Yonge Street, Suite 412, Toronto, Ontario M2P 2B5 Phone: (416) 222-5100 Fax: (416) 222-8452 Daily Access Hours are 6:00 am - 7:00 pm, After Hours Access is 7:00 pm - 6:00 am THE CADILLAC FAIRVIEW CORPORATION Cadillac Fairview is one of North America’s largest investors, owners and managers of commercial real estate. -

NORTH YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER AUGUST-OCTOBER, 2011 1960-2011: 51St Year [email protected]

NORTH YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER AUGUST-OCTOBER, 2011 1960-2011: 51st Year www.nyhs.ca [email protected] From the President The end of an era: since the mid-1960s, the Society has had a connection with the Gibson House Museum. In 1964, the Borough of North York acquired the Gibson House. It was officially opened as a museum in 1971, with the support of the Society, historical interpreters, exhibits, displays and an annual festival. The Gibson House Volunteers were a sub-committee of the NYHS, and after amalgamation, they became City of Toronto volunteers. Through the years the Society has had representation on the GH Museum Board and post amalgamation, one appointee. City of Toronto museum boards have now been dissolved by Council. See page 2 for more information. A reminder to members, the October meeting program: C. W. Jefferys: Picturing Canada – his daughter, Mrs. Elizabeth Fee (1912-2010) was the Society’s Honourary President for many years. Congratulations to the 2011 recipients of the Volunteer Service Awards. See page 2. Geoff Geduld Wednesday, September 21st, 7.30 p.m. HERITAGE TREES: PRESERVING OUR NATURAL ROOTS LOCATION Edith George, past director of the Weston Historical Society & North York Central Library advisor to the Ontario Urban Forest Council. Meeting Room #1 How we can identify a tree’s historical and cultural significance? 2nd floor Using a special red oak as the example in her presentation, find 5120 Yonge Street out what is a heritage tree and why is it important to protect it. (at Park Home Ave) West side of atrium, Wednesday, October 19th, 7.30 p.m. -

West Toronto Diamond

West Toronto Diamond Brent Archibald, P.Eng. Vic Anderson, MSc (London), DIC, P.Eng. Joanne Crabb, P.Eng.,ing., PE Jonathan Werner, M.A.Sc., P.Eng. Paper prepared for presentation at the Bridges: Economic and Social Linkages Session of the 2007 Annual Conference of the Transportation Association of Canada Saskatoon, Saskatchewan Abstract This paper describes the West Toronto Diamond project in Ontario, Canada. This project has been designed to eliminate at-grade diamond crossings of the Canadian National Railway (CN) and the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) tracks in the Junction area of Toronto, an area which takes its name from the confluence of these railways. Since the 1880’s, rail traffic here has been constrained by these diamond crossings involving the CN and CPR mainlines and a CPR Wye track. The project will result in a quantum improvement in the levels of service and safety provided by the Railways at this site. The project involves relocating the CN tracks below the CPR tracks, while at the same time maintaining all rail operations with a minimum of interruption to the Railways’ activities. The site is physically constrained and hence, in order to accomplish this goal, Delcan’s design includes the sliding of 4 mainline railway bridge spans, weighing a total of some 10,000 tonnes, into their final positions. Each slide occupies only a few hours, as it is powered by computerized high-speed tandem hydraulic jacks, moving these massive structures on steel / aluminum bronze slide paths, enabling the bridge spans to move quickly and continuously into position during brief possessions of the tracks. -

Attached Detailed Report

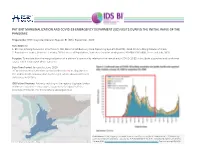

PATIENT MARGINALIZATION AND COVID-19 EMERGENCY DEPARMENT (ED) VISITS DURING THE INITIAL WAVE OF THE PANDEMIC Prepared by: HHS Integrated Decision Support BI (IDS), September, 2020 Data Sources: 1. ED Visit & Marginalization Information: IDS: National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (NACRS), 2016 Ontario Marginalization Index 2. Population Counts: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census of Population, Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-400-X2016003. Accessed July, 2020. Purpose: To explore how the marginalization of a patient's community relates to the rate of adult COVID-19 ED visits (both suspected and confirmed cases) in the inital wave of the pandemic. Data Time Period: January to June, 2020 > For context, this is the time period outlined in red as displayed in the Public Health Ontario chart to the right, which shows confirmed daily cases in Ontario. IDS Patient Regions: Patients residing in the regions displayed below in blue are included in this report, accounting for about half the province of Ontario. For more details see Appendix A. Chart Source: Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario). Epidemiologic summary: COVID-19 in Ontario – January 15, 2020 to September 20, 2020. Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for © 2020 Mapbox © OpenStreetMap Ontario; 2020. https://files.ontario.ca/moh-covid-19-report-en-2020-09-21.pdf. Accessed on Sept 21, 2020. Rate of COVID-19 ED Visits Per 10,000 Adult Population, by Ontario Marginalization Dimensions Summary Table All IDS Patient Regions, Adults Only, Jan to Jun 2020 IDS Patient -

Social Services Funding Agencies

TO Support Cluster Service Area Agency Name Allocation Amount Communities Being Served Emergency Food Community Kitchens Kingston Rd/Galloway, Orton Park, and West Scarborough East Scarborough Boys and Girls Club $ 327,600.00 Hill communities (Wards 23, 24, 25), plus extended service to Wards 20 and 22. Primarily east Toronto and Scarborough 5N2 Kitchen within the boundaries of DVP and Woodbine, East Toronto and Scarborough $ 99,600.00 Danforth, Finch and Port Union; also delivering to vulnerable populations Downtown East and West, Regent Park, Downtown; Scarborough; Etobicoke Kitchen 24 $ 96,000.00 Scarborough, North Etobicoke Hospitality Workers Training Centre Downtown; Scarborough $ 78,000.00 South East Toronto (HWTC, aka Hawthorn Kitchen) Toronto Drop-in Network ( 51 Various locations across the City, City-wide $ 140,564.00 agencies) concentration downtown City-wide FoodShare $ 150,000.00 Various NIAs, especially Tower Communities Downtown West, High Park, and Downtown Toronto Feed It Forward $ 72,000.00 Parkdale Across Toronto serving those with mental City-Wide Bikur Cholim $ 10,000.00 health conditions, & vulnerable seniors African (East and West, Caribbean) and Black communities in Black Creek Black Creek Community Health Humber Summit cluster area, Glenfield- North Etobicoke $ 60,000.00 Centre Jane Heights, Kingsview Village- The Westway, Beaumonde Heights, Mt. Olive- Silverstone-Jamestown Community Food Providers City-wide Daily Bread Food Bank $ 150,000.00 City-wide Second Harvest $ 150,000.00 City-wide Salvation Army $ 150,000.00 -

Chapter 7 Site and Area Specific Policies

CHAPTER 7 SITE AND AREA SPECIFIC POLICIES Throughout the City are sites and areas that require policies that vary from one or more of the provisions of this Plan. These policies generally reflect unique historic conditions for approval that must be recognized for specific development sites, or provide a further layer of local policy direction for an area. In most cases, the site and area specific policies provide direction on land use. The Plan policies apply to these lands except where the site and area specific policies vary from the Plan. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. South of Steeles Avenue, West of Alcide Street .......................................................................................... 13 2. West Side of The West Mall, East of Etobicoke Creek ................................................................................. 13 3. 124 Belfield Road ........................................................................................................................................ 14 4. Monogram Place.......................................................................................................................................... 14 5. 20 Thompson Avenue .................................................................................................................................. 14 6. South Side of The Queensway, Between Zorra Street and St. Lawrence Avenue, North of the Gardiner Expressway ................................................................................................................................................ -

October 2 Heaps Estrin Newsletter-Smaller

FROM THE TEAM FEATURED PROPERTIES FALL FESTIVITIES REAL ESTATE TEAM FROM THE TEAM Welcome to the Autumn Edition of Your Best Move Newsletter Toronto always feels special as the We have consummate professionals in 30,000 women and children who have temperatures cool and the leaves change each role working harmoniously towards become victims of domestic abuse. The colour. It may be a busy time of the year, our clients needs. Providing a full-service foundation has helped raise more than but it’s also beautiful. We hope you are team at the cost of a single practitioner 20 million dollars and supports two - enjoying autumn and trust you had a is the backbone to our success. Every hundred local women’s shelters and their relaxing Thanksgiving with loved ones. team member loves what they do and national partners. There are plenty of fascinating things are always happy to help in any capacity going on around the city and we have they can. We appreciate the steadfast I am sending warm wishes to all of you prepared a list of the highlights. Our praise and referrals of friends and family, as the temperature begins to plummet. team is planning a pumpkin patch party and look forward to working with more Should you ever have questions or if we at our office on October 18th, which is of you. can be of some assistance, please call or sure to be a great time. Bring along the email. We would love to hear from you. kids for fun activities, treats and pick up a We are grateful for our success and are complementary pumpkin for Halloween. -

Allocations to Agencies (For the Period April 1, 2015 to March 31, 2016)

Allocations To Agencies (for the period April 1, 2015 to March 31, 2016) The following is a list of agencies that United Way Toronto & York Region funded, with the corresponding dollar amounts: Agency Name Allocation 360° Kids Support Services $104,137 519 Church Street Community Centre $199,318 Abrigo Centre $267,083 ACCES Employment $237,092 Access Alliance Multicultural Health and Community Services $158,000 Agincourt Community Services Association $423,065 Aisling Discoveries Child and Family Centre $200,026 Albion Neighbourhood Services $441,381 Alzheimer Society of York Region $74,669 Anishnawbe Health Toronto $191,925 Barbra Schlifer Commemorative Clinic $206,416 Baycrest Centre for Geriatric Care $312,281 Bernard Betel Centre for Creative Living $214,921 Big Brothers Big Sisters of Toronto $396,019 Big Brothers Big Sisters of York $85,816 Birchmount Bluffs Neighbourhood Centre $215,180 Bloor Information and Life Skills Centre $311,819 Blue Door Shelters $372,593 Bond Child and Family Development $15,788 Braeburn Neighbourhood Place $419,367 Call-A-Service Inc./Harmony Hall Centre for Seniors $189,579 Canadian Centre for Victims of Torture $242,193 Canadian Hearing Society - Simcoe York Region (The) $175,849 Canadian Hearing Society - Toronto Region (The) $618,964 Canadian Mental Health Association Toronto Branch $628,605 Canadian Mental Health Association, York Region $192,956 Canadian Red Cross Society - Region of York Branch $64,637 1 Agency Name Allocation Canadian Red Cross - Toronto Region (The) $2,565,013 CANES Community Care $185,801 Carefirst Seniors & Community Services Association $484,156 Catholic Community Services of York Region $104,450 Cedar Centre (formerly York Region Abuse Program) $184,160 Central Neighbourhood House Association, one of The $752,246 Neighbourhood Group Centre for Immigrant & Community Services of Ontario $658,247 Centre For Independent Living in Toronto (C.I.L.T.) Inc.