Teen Action Heroines and the Logic of Anorexia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reading for Pleasure? Try a Little Something from Our Taster Menu

READING FOR PLEASURE? TRY A LITTLE SOMETHING FROM OUR TASTER MENU... Edition Looking for something to read but don’t know where to begin? Dip into these pages and see if something doesn’t strike a spark. With over thirty titles (many of which come recommended by the organisers of World Book Day - including a number of best sellers), there is bound to be something to appeal to every taste. There is a handy, interactive contents page to help you navigate to any title that takes your fancy. Feeling adventurous? Take a lucky dip and see what gems you find. Cant find anything here? Any Google search for book extracts will provide lots of useful websites. This is a good one for starters: https://www. penguinrandomhouse.ca/books If you find a book you like, there are plenty of ways to access the full novel. Try some of the services listed below: Chargeable services Amazon Kindle is the obvious choice if you want to purchase a book for keeps. You can get the app for both Apple and Android phones and will be able to buy and download any book you find here. If you would rather rent your books, library style, SCRIBD is the best app to use. They charge £8.99 per month but you can get the first 30 days free and cancel at any time. If you fancy listening to your favourite stories being read to you by talented voice recording artists and actors, tryAudible : they offer both one off purchases and subscription packages. Free services ORA provides access to myON and you will have already been given details for how to log in. -

Contwe're ACT

CHART-TOPPING MUSIC SENSATION ARIANA GRANDE ANNOUNCES THE HONEYMOON TOUR IN SUPPORT OF HER BILLBOARD #1 ALBUM, MY EVERYTHING – Pop Music's Biggest Breakout Star of the Year Kicks Off First North American Headlining Tour on Feb. 25, 2015 in Kansas City, Mo. and Includes Dates at Arenas in 25 Cities Across the U.S. and Canada – – Tickets On Sale Sept. 20 at LiveNation.com and through the Live Nation Mobile App – LOS ANGELES (Sept. 10, 2014) – Pop music's biggest breakout star of the year, Ariana Grande, announced today details for her first North American headlining tour in support of her Billboard #1 album, My Everything. Produced and promoted exclusively by Live Nation, THE HONEYMOON TOUR will kick off Feb. 25, 2015 at the Independence Event Center in Kansas City, Mo. The 25-date tour will visit arenas throughout the U.S. and Canada, including stops in Los Angeles, New York City, Toronto, Vancouver, Washington, D.C., Chicago, Dallas, Miami and more. Tickets go on sale Saturday, Sept. 20 at www.livenation.com and through the Live Nation mobile app. Always keeping her fans in mind, Ariana first revealed the tour dates via Fahlo—her new fan club—on Friday, Sept. 5. The innovative community even allows fans to interact and communicate about each tour date as well. Visit the hub here! Moreover, pre-sale tickets will go on sale for all fan club members who download the Fahlo app. Ariana fan club members and VIP Nation members will have access to the pre-sale starting Monday, Sept. 15 through Friday, Sept. -

UAE Lists Brotherhood As a 'Terrorist Group'

SUBSCRIPTION SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 16, 2014 MUHARRAM 23, 1436 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Road accidents Obama gets Triumphant Gritty Djokovic killed 225 glimpse of probe sends subdues people in life as lame last-gasp data Nishikori to six months4 duck14 abroad from28 ‘alien world’ reach17 final UAE lists Brotherhood Min 11º Max 29º as a ‘terrorist group’ High Tide 05:16 & 19:44 Over 80 other Islamist outfits blacklisted Low Tide 00:12 & 12:33 40 PAGES NO: 16344 150 FILS DUBAI: The United Arab Emirates has for- Yesterday’s move echoes a similar move the UAE for its alleged link to Egypt’s abide by an agreement not to interfere in conspiracy theories mally designated the Muslim Brotherhood by Saudi Arabia in March and could Muslim Brotherhood, as a terrorist group. one another’s internal affairs. So far efforts and local affiliates as terrorist groups, state increase pressure on Qatar whose backing UAE authorities have cracked down on by members of the GCC, an alliance that news agency WAM reported yesterday, cit- for the group has sparked a row with fel- members of Al-Islah and jailed scores of also includes Oman and Kuwait, to resolve Let’s do some math ing a cabinet decree. The Gulf Arab state low Gulf monarchies. It also underscores Islamists convicted of forming an illegal the dispute have failed. The three states has also designated Nusra Front and the concern in the US-allied oil producer branch of the Brotherhood. Al-Islah denies mainly fell out with Qatar over the role of Islamic State, whose fighters are battling about political Islam and the influence of any such link, but says it shares some of Islamists, including the Muslim Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad, as terror- the Brotherhood, whose Sunni Islamist the Brotherhood’s Islamist ideology. -

Contwe're ACT

ARIANA GRANDE MULTI-PLATINUM SELLING & GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATED ARTIST ANNOUNCES THE DANGEROUS WOMAN TOUR – North American Headlining Tour Kicks Off on Feb. 2, 2017 in Phoenix, AZ and Includes Over 30 Shows in Cities Across the U.S. and Canada – – Tickets On Sale Sept. 24 at LiveNation.com – LOS ANGELES (Sept. 19, 2016) – Multi-platinum selling and Grammy Award-nominated artist, Ariana Grande, today revealed details behind her biggest tour yet - THE DANGEROUS WOMAN TOUR. Produced and promoted exclusively by Live Nation, THE DANGEROUS WOMAN TOUR will kick off Feb. 2, 2017 at the Talking Stick Arena in Phoenix, Ariz. and includes 36 dates in cities throughout North America, including stops in Los Angeles, New York City, Toronto, Vancouver, Washington, DC, Chicago, Dallas, Miami and more. "Ariana Grande is an incredible performing artist and American Express is excited to partner with her on the DANGEROUS WOMAN TOUR. We are excited to bring our Card Members, who are her fans, an opportunity to purchase tickets before the general on-sale date,” said Walter Frye, Vice President of Global Entertainment and Premier Events at American Express. "Our Card Members have a strong passion for music and Ariana's tour is sure to deliver an exceptional music experience." American Express® Card Members can purchase tickets before the general public beginning Tuesday, September 20 at 10am local through Friday, September 23 at 10pm local. Tickets go on sale Saturday, September 24 at www.livenation.com. Within less than a year, ARIANA GRANDE captured No. 1 on the Billboard Top 200 twice—first with her Republic Records debut “Yours Truly” and also with its 2014 follow-up, “My Everything.” “Yours Truly” yielded the game-changing pop smash “The Way” featuring Mac Miller, which went triple- platinum, landed in the Top 10 of the Billboard Hot 100, and seized No. -

Becky G Joins Jason Derulo’S Talk Dirty Tour Single “Shower” Sold Over Half a Million Units

BECKY G JOINS JASON DERULO’S TALK DIRTY TOUR SINGLE “SHOWER” SOLD OVER HALF A MILLION UNITS (Los Angeles, CA) – Becky G will join Jason Derulo’s Talk Dirty tour which kicks off on October 21st at the Starland Ballroom in New Jersey and wraps on November 2nd at the Filmore in Miami. Becky’s latest single “Shower” has sold over half a million units. Her performances of “Shower” on NBC’s Today Show and FOX’s Teen Choice Awards earned her high praise. “Becky G was the youngest performer on the 2014 Teen Choice Awards stage, but you would never know it from her awesome-beyond-her-years performance of ‘Shower’. Becky G worked that stage like nobody’s business, singing her heart out and flaunting some seriously killer dance moves.” (PopCrush) The music video for “Shower” premiered earlier this summer and was presented exclusively in partnership with COVERGIRL. Check out the video here. The video was directed by Tim Nackashi and shot in Los Angeles. “Shower” is produced by Dr. Luke & Cirkut for Prescription Songs and written by Becky G, Dr. Luke, Rock City (Theron Thomas & Timothy Thomas) and Henry Walter. Becky is one of COVERGIRL’s newest and youngest faces who won “The Best New Artist” award on Radio Disney Music Awards. She has also scored her first #1 single “Can’t Get Enough” feat. Pitbull on Latin Billboard Charts. Additionally, Becky wrapped her first major support tour with Austin Mahone and appeared on the cover of the April/May issue of Girls’ Life Magazine. Becky G is a 17-year-old singer, songwriter, and rapper who is signed with Kemosabe / RCA Records. -

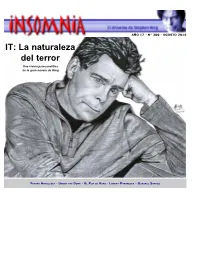

Acceder a INSOMNIA Nº

AÑO 17 - Nº 200 - AGOSTO 2014 IT: La naturaleza del terror Una visión psicoanalítica de la gran novela de King FUTURA ANTOLOGÍA - UNDER THE DOME - EL POP DE KING - LAMENT PARANOIKA - GONZALO SANTOS Nº 200 - AGOSTO 2014 PORTADA La imagen de portada de este mes IT: LA NATURALEZA es un dibujo original de nuestro DEL TERROR EDITORIAL colaborador, redactor y traductor Alejandro Ginori. Una pequeña obra Una visión NOTICIAS de arte (hablando del tamaño, no psicoanalítica de la A FONDO de la calidad)... gran novela de King INFORME PÁG. 3 Conforme avanzan, no sin cierto frenesí, las vastas concepciones EDICIONES científicas que a posteriori THE DOME inundan el terreno harto sugestionable de la opinión O ICCIÓN • Una extracto en castellano de la N -F pública, resulta paulatinamente novela Mr Mercedes ORTOMETRAJES más inadecuado e ilícito enfatizar C • Ediciones aniversario de varios y referirse a la “naturaleza” de libros de King FICCIÓN las cosas. El desarrollo de las • Se editan dos audiolibros de King ciencias sociales, inclusive cierta OTROS MUNDOS en castellano parcela de las “ciencias • Detours, una nueva antología que CONTRATAPA naturales”, adjudican un rol incluye Memory, extracto de la protagónico, relativo a los novela Duma Key desencadenantes fenoménicos de • Joyland, por error los procesos madurativos en general y patrones ... y otras noticias comportamentales en particular, PÁG. 4 a los factores procedentes del influjo socio-cultural. PÁG. 23 Ingredientes para una nueva antología Lament Paranoika, Episodios Hace unas semanas conocíamos la de Darek Kocurek 14 al 17 noticia de que Stephen King editará en otoño de 2015 —fecha tentativa El 19 de junio de 1999 Stephen Ha vuelto Under the Dome. -

Dylan O Brien New Girl

Dylan o brien new girl Continue American actor Dylan O'Brien at the 2017 San Diego Comic-ConBorn (1991-08-26) August 26, 1991 (age 29)New York, New York, USA EducationWorld Costa High SchoolOccupationActorYears active2011-present Dylan O'Brien (born August 26, 1991) is an American actor. He is best known for his starring role as Thomas in the dystopian sci-fi trilogy The Maze Runner and the role of Stiles Stillinsky in MTV's Little Wolf. O'Brien's other work includes starring roles in such films as First Time and American Killer, as well as supporting roles in the films Internship and Deepwater Horizon. Early life O'Brien was born in New York, the son of Lisa (nee Rhodes), a former actress who also ran acting school, and Patrick O'Brien, a cameraman. He grew up in Springfield Township, New Jersey, until he was twelve years old when he and his family moved to Hermosa Beach, California. His father is of Irish descent and his mother of Italian, English and Spanish descent. After graduating from Mira Costa High School in 2009, he confers to engage in sports broadcasting and possibly work for the New York Mets. At the age of 14, O'Brien began posting original videos on his YouTube channel. With the video developing, a local producer and director approached him about doing the work for a web series while in his senior year of high school. While working on the web series, O'Brien met the actor, who connected him with the manager. He had planned to enter Syracuse University as a sports broadcasting major, but instead decided to pursue an acting career. -

Concerts/Tours/Events

11/26/2019 Rhapsody James | CONCERTS/TOURS/EVENTS Janet Jackson “Metamorphosis” Las Vegas Residency 2019 Choreographer Park MGM Las Vegas / Dir: Gil Duldulao Gwen Stefani “Just A Girl” Las Vegas Residency (Underneath It All) 2019 Contributing Choreographer Planet Hollywood Las Vegas / Dir: Luther Brown Chris Brown / Heartbreak on a Full Moon Tour 2018 Contributing Choreographer Dir: Josh Smith Trey Songz / Between the Sheets Tour 2016 Choreographer Dir: Barry Lather Puff Daddy / Bad Boy Family Reunion Tour 2015 Choreographer Dir: Laurie Ann Gibson Ariana Grande / Honeymoon Tour 2015 Contributing Choreographer Dir: Nick Demoura / Brian & Scott Nicholson Contributing Choreographer Dir: Nick Demoura / Brian & Scott Nicholson Ciara / The Jackie Tour 2015 Contributing Choreographer Dir: Jamaica Craft Contributing Choreographer Dir: Jamaica Craft TLC / Main Event Tour 2015 Associate Director Dir: Jamaica Craft Demi Lovato World Tour Contributing Choreographer Dir: Gil Duldulao Mariah Carey/ The Elusive Chantuse Show 2014 Contributing Choreographer Dir: Eddie Morales Britney Spears / The Circus Tour 2009 Asst. Choreographer Dir: Jamie King Spice Girls Reunion Tour 2009 Asst. Choreographer Dir: Jamie King Beyonce / The Beyonce Experience 2007 Contributing Choreographer Dir: Frank Gatson Cassie / NFL Kick Off Concert 2006 https://msaagency.com/portfolio/rhapsodyjames/ 1/4 11/26/2019 Rhapsody James | Choreographer Dir: Laurie Ann Gibson Betsey Johnson Fashion Show 2005 Movement Coach Betsey Johnson AWARD SHOWS 2018 MTV Video Music Awards - Logic Staging Choreographer MTV/ Dir: Barry Lather 2017 BET AWARDS - Trey Songz Choreographer BET / Dir: Barry Lather 2016 GRAMMY AWARDS - Pitbull Choreographer ABC 2015 MTV Video Music Awards - Nicki Minaj Choreographer MTV 2015 BET AWARDS - Puff Daddy & Bad Boy Choreographer BET 2015 TIDAL Music Festival – Nicki Minaj & Beyonce Choreographer Dir: Laurie Ann Gibson 2014 BET AWARDS - Trey Songz Choreographer BET / Dir: Barry Lather 2014 TEEN CHOICE AWARDS – Demi Lovato Asst. -

AA-Postscript 2.Qxp:Layout 1

lifestyle SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 16, 2014 Gossip Khloe Kardashian proud of Kim West’s nude photo shoot he ‘Keeping Up With The Kardashians’ star credited her big sister TKim for stripping off in a recent shoot for Paper magazine and thinks the 34-year-old mother of one looks “incredible”. She told E! News: “You know what? If you’ve got it, flaunt it. I think Kim has an amazing body, she looks incredible. To each their own. “I think Kim looks great and if you have the confidence to do that, more power to you. And people just, I think, went so hard on her during her pregnan- cy that I think it’s almost that she feels so liberated to show everyone, like, ‘Look how bomb I look.’ And she does, she looks great.” Khloe, 30, went on to praise the brunette beauty’s relationship with her husband Kanye West and revealed they decided Kim would star in the contro- versial full frontal shoot together. She explained: “The thing that I love about Kim and Kanye, they do things together, like that’s something they both agreed to do as a couple—even though it was just Kim—but they discuss it and they both think it’s art and it’s cool, and that’s their thing.” Along with the nude shots, Kim - who has 16-month-old daugh- ter, North, with the ‘Bound 2’ rapper - also recreated French photogra- pher Jean-Paul Goude’s famous “Champagne Incident” for the cover of the New York magazine. She shared the image on her Instagram account, along with the caption: “Paper Magazine new cover alert! - such a honor to work with the legendary Jean-Paul Goude!!!! Shot this in Paris. -

ARTBA National Convention 2015

ARTBA National Convention 2015 September 29-October 1 Hilton Philadelphia at Penn’s Landing Program of Events www.artbanationalconvention.org 2015 ARTBA National Convention 1 2 2015 ARTBA National Convention A COMPLETE LINE OF PAVING SOLUTIONS. 9 24/7 support 9 One-stop equipment, parts, Discover a world of service 9 Dedicated and highly service and rental and value. Contact your trained paving specialists 9 Flexible financial incentives local Cat® dealer today. CS34 CP44B CP54B CP56B CP68B CP74B CS34 CS44B CS54B CS56B CS68B CS74B CS78B AP255E AP500E AP555E AP600F AP655F AP1000F AP1055F AS3143 AS3251CAS4252C SE60 V SE60 V XW SE60 V SE60 V XW SE60 VT XW CB14B CB14B CB22B CB24B CB24B XT CB32B CC24B CB34B CB36B CC34B 900 mm (35") 1000 mm (39") Combi Combi CB44B CB54B CB64B CB66B CB68B CD44B CD54B CW14 CW14 HW CW34 RM300 RM500B PM102 PM102 PM200 PM200 (Track) (Wheel) (2.0 m) (2.2m) Find us online at www.cat.com/paving facebook.com/CATPaving youtube.com/CATPaving R QEXC1798-02 © 2015 Caterpillar. All Rights Reserved. CAT, CATERPILLAR, BUILT FOR IT, their respective logos, “Caterpillar Yellow,” the “Power Edge” trade dress as well as corporate and product identity used herein, are trademarks of Caterpillar and may not be used without permission. 2015 ARTBA National Convention 3 © 2015 Webber LLC. All rights reserved. INTELLIGENT INFRASTRUCTURE STARTS HERE Webber is an American construction company with global resources, dedicated to safely providing intelligent infrastructure solutions to our clients and community. With over 150 engineers globally, best-in-class technology and virtually unlimited resources, Webber is able to build better and manage smarter. -

Kevin Maher Television

Kevin Maher Television: Jump, Jive & Thrive Creative Director CBS Hailee Steinfeld- Staging + Choreographer Today Show Dancing With The Stars w/ Choreographer ABC Selena Gomez The X-Factor UK w/ The Choreographer Wanted The Voice Australia w/ The Choreographer Wanted So You Think You Can Dance Choreographer Australia w/ Jason Derulo American Idol w/ Carly Rae Choreographer FOX Jepsen American Idol w/ Jason Derulo Choreographer FOX American Idol w/ The Wanted Choreographer Island Def Jam Music Group Victoria Secret Fashion Show Choreographer BT Touring, LLC (Multiple w/ Justin Bieber Years) 15 Awesomest Boy Bands Choreographer E! Network All Around The World / Justin Contributing Choreographer NBC Bieber Special Marvin, Marvin w/ Big Time Series Choreographer Nickelodeon Rush Big Time Rush Series Choreographer Nickelodeon Big Time Rush "Big Time Choreographer Nickelodeon Tour" NBC's Fashion Star Choreographer NBC (Multiple Episodes) The Jay Leno Show w/ Jason Choreographer NBC Derulo The View w/ Jason Derulo, Choreographer ABC New Kids on the Block, Victoria Justice The Ellen DeGeneres Show Choreographer NBC w/ Fifth Harmony The Ellen DeGeneres Show Choreographer NBC w/ Jason Derulo The Arsenio Hall Show w/ Choreographer CBS Fifth Harmony Lopez Tonight w/ Jason Choreographer TBS Derulo, Iyaz The Today Show w/ Fifth Choreographer NBC Harmony The Today Show w/ Justin Choreographer NBC Bieber / "All Around the World" The Today Show w/ New Kids Choreographer NBC on the Block Late Night with Jimmy Fallon Choreographer NBC w/ New Kids on the Block Rock The Cradle Performance Coach MTV Network America's Got Talent Assoc. Choreographer NBC LXD - Webisodes 5, 6, 7 Asst. Choreographer Dir.