SOUTH AFRICA Mapping Digital Media: South Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

South African tabloid newspapers’ representation of black celebrities: A social constructionism perspective Emmanuel Mogoboya Matsebatlela Dissertation presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy (Journalism) at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Josh Ogada September 2009 DECLARATION I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this dissertation is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature: Date: (Emmanuel Mogoboya Matsebatlela) Copyright © 2009 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the following people: . My supervisor, Josh Ogada, for his expert and invaluable guidance throughout the course of my studies. Professor Alet Kruger for helping me with the translations. The University of South Africa for providing me unrestricted access to their library facilities. My parents, John and Paulina Matsebatlela, for their unwavering support and constant encouragement. My wife, Molebogeng, for her patience, motivation and support. 2 DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this study to my late Uncles, Rangwane M’phalaborwa ‘Mamodila Selemantwa’ Matsebatlela and Malome Thomas Mahlo. Though their life journeys have ended, they will forever remain etched in our memories. May their souls rest in peace. 3 ABSTRACT This study examines how positively or negatively as well as how subjectively or objectively the South African tabloid newspapers represent black celebrities. This examination was primarily conducted by using the content analysis research technique. The researcher selected a total of 85 newspapers spread across four different South African daily and weekend tabloid newspapers that were published during the period February to September 2008. -

Who Owns the News Media?

RESEARCH REPORT July 2016 WHO OWNS THE NEWS MEDIA? A study of the shareholding of South Africa’s major media companies ANALYSTS: Stuart Theobald, CFA Colin Anthony PhibionMakuwerere, CFA www.intellidex.co.za Who Owns the News Media ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We approached all of the major media companies in South Africa for assistance with information about their ownership. Many responded, and we are extremely grateful for their efforts. We also consulted with several academics regarding previous studies and are grateful to Tawana Kupe at Wits University for guidance in this regard. Finally, we are grateful to Times Media Group who provided a small budget to support the research time necessary for this project. The findings and conclusions of this project are entirely those of Intellidex. COPYRIGHT © Copyright Intellidex (Pty) Ltd This report is the intellectual property of Intellidex, but may be freely distributed and reproduced in this format without requiring permission from Intellidex. DISCLAIMER This report is based on analysis of public documents including annual reports, shareholder registers and media reports. It is also based on direct communication with the relevant companies. Intellidex believes that these sources are reliable, but makes no warranty whatsoever as to the accuracy of the data and cannot be held responsible for reliance on this data. DECLARATION OF CONFLICTS Intellidex has, or seeks to have, business relationships with the companies covered in this report. In particular, in the past year, Intellidex has undertaken work and received payment from, Times Media Group, Independent Newspapers, and Moneyweb. 2 www.intellidex.co.za © Copyright Intellidex (Pty) Ltd Who Owns the News Media CONTENTS 1. -

Blurred Lines

BLURRED LINES: HOW SOUTH AFRICA’S INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM HAS CHANGED WITH A NEW DEMOCRACY AND EVOLVING COMMUNICATION TOOLS Zoe Schaver The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Media and Journalism Advised by: __________________________ Chris Roush __________________________ Paul O’Connor __________________________ Jock Lauterer BLURRED LINES 1 ABSTRACT South Africa’s developing democracy, along with globalization and advances in technology, have created a confusing and chaotic environment for the country’s journalists. This research paper provides an overview of the history of the South African press, particularly the “alternative” press, since the early 1900s until 1994, when democracy came to South Africa. Through an in-depth analysis of the African National Congress’s relationship with the press, the commercialization of the press and new developments in technology and news accessibility over the past two decades, the paper goes on to argue that while journalists have been distracted by heated debates within the media and the government about press freedom, and while South African media companies have aggressively cut costs and focused on urban areas, the South African press has lost touch with ordinary South Africans — especially historically disadvantaged South Africans, who are still struggling and who most need representation in news coverage. BLURRED LINES 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I: Introduction A. Background and Purpose B. Research Questions and Methodology C. Definitions Chapter II: Review of Literature A. History of the Alternative Press in South Africa B. Censorship of the Alternative Press under Apartheid Chapter III: Media-State Relations Post-1994 Chapter IV: Profits, the Press, and the Public Chapter V: Discussion and Conclusion BLURRED LINES 3 CHAPTER I: Introduction A. -

RATE CARD 2018 Contents

RATE CARD 2018 Contents 1. Digital Rates 2. Newspaper Rates 3. Local Titles Insert Rates 4. Magazine Rates 5. Material & Insert Deadlines 6. Column Sizes ϳ͘ dĞƌŵƐĂŶĚŽŶĚŝƟŽŶƐ 8. Contact Details ůůƌĂƚĞƐĂƌĞEĞƩĂŶĚĞdžĐůƵĚĞsd ZĂƚĞƐĞīĞĐƟǀĞƉƌŝůϮϬϭϴʹDĂƌĐŚϮϬϭϵ ĂŶĐĞůůĂƟŽŶĨĞĞǁŝůůďĞĐŚĂƌŐĞĚĨŽƌůĂƚĞĐĂŶĐĞůůĂƟŽŶƐ 1 1. Rates Digital ZĂƚĞƐĂŶĚWƵďůŝĐĂƟŽŶ/ŶĨŽƌŵĂƟŽŶMonday - Saturday Click on a heading below to navigate to that page Digital Rates Netwerk 24 City Press Son <ŝĐŬKī Ϯ͘ EĞǁƐƉĂƉĞƌ Netnuus Daily Sun Soccer Laduma Kuier Rates WƌŝŶƚZĂƚĞƐ DŽŶĚĂLJͲ&ƌŝĚĂLJ DŽŶĚĂLJͲ^ĂƚƵƌĚĂLJ Sunday Titles Daily Sun Beeld City Press Son Die Burger Rapport Volksblad Son op Sonday Volksblad 3. Tiltes Local DŽŶĚĂLJͲ&ƌŝĚĂLJtĞĚŶĞƐĚĂLJ /ŶƐĞƌƚZĂƚĞƐ The Witness & Weekend Witness Sunday Sun Soccer Laduma >ŽĐĂůdŝƚůĞƐ/ŶƐĞƌƚZĂƚĞƐ ĂƐƚĞƌŶĂƉĞdŝƚůĞƐ tĞƐƚĞƌŶĂƉĞ͗WĞŶŝŶƐƵůĂdŝƚůĞƐ Maritzburg Echo Isolomzi Express City Vision Lagunya ^ŽƵƚŚŽĂƐƚ&ĞǀĞƌ Kouga Express City Vision Khayelitsha Mid-Karoo Express >ŝŵƉŽƉŽdŝƚůĞƐ ŝƚLJsŝƐŝŽŶ>ǁĂŶĚůĞͬEŽŵnjĂŵŽ 4. Magazine Mthatha Express Rise ‘n Shine People’s Post Athlone Rates PE Express DƉƵŵĂůĂŶŐĂdŝƚůĞƐ WĞŽƉůĞ͛ƐWŽƐƚƚůĂŶƟĐ^ĞĂͲŽĂƌĚͬ Queenstown Express ŝƚLJĚŝƟŽŶ UD Express Cosmos News WĞŽƉůĞ͛ƐWŽƐƚůĂƌĞŵŽŶƚͬ Rondebosch &ƌĞĞ^ƚĂƚĞdŝƚůĞƐ EŽƌƚŚtĞƐƚdŝƚůĞƐ WĞŽƉůĞ͛ƐWŽƐƚŽŶƐƚĂŶƟĂͬtLJŶďĞƌŐ Bloemnuus ĂƌůĞƚŽŶǀŝůůĞ,ĞƌĂůĚ WĞŽƉůĞΖƐWŽƐƚ&ĂůƐĞĂLJ Midweek Potchefstroom Herald /ŶƐĞƌƚĞĂĚůŝŶĞƐ Express ϱ͘ DĂƚĞƌŝĂůΘ People's Post Grassy Park Kroonnuus Potchefstroom Herald People's Post Landsdowne Vista Leseding News Bojanala People’s Post Michell’s Plain Vrystaat Nuus EŽƌƚŚĞƌŶĂƉĞdŝƚůĞƐ People’s Post -

Annual Report: April 2002 to May 2003

ANNUAL REPORT: APRIL 2002 TO MAY 2003 INTRODUCTION 1. Both National and International circumstances have had a telling impact on the work of the Commission during the current year. The Middle-east conflict led to several complaints emanating from South African supporters of the two sides involved in the conflict. The war in Afghanistan also led to some complaints, but in this case the general impact on our work was less serious. The Broadcasting Amendment Act 2002 granted the Independent Communications Authority of South Africa the authority to make regulations which repealed the Broadcasting Code and replaced it with what has become known as the ICASA Code. This Commission is bound by this Code and, as from 7 th March 2003, all broadcasters that fall under the jurisdiction of this Commission (approximately 50 in number) have been subject to the new Code. 2. After the Constitutional Court decided in April 2002 that the Broadcasting Code was too wide in its prohibition relating to material that is harmful to relations between sections of the population, several judgments of this Commission were published in 2 the light of the new criteria. The criterion laid down by the Constitutional Court is that the old provision should be limited to material that makes propaganda for war, incites to violence, and also material that amounts to the advocacy of hatred based on race, ethnicity, gender or religion, and which constitutes incitement to cause harm. Thereafter, the first complaint that faced this Commission was a song written by a well known South African songwriter, Mbongeni Ngema. -

Informal Settlement Upgrading in Cape Town’S Hangberg: Local Government, Urban Governance and the ‘Right to the City’

Informal Settlement Upgrading in Cape Town’s Hangberg: Local Government, Urban Governance and the ‘Right to the City’ by Walter Vincent Patrick Fieuw Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy in Sustainable Development Planning and Management in the Faculty of Economics and Management Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Dr Firoz Khan December 2011 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Signature Walter Fieuw Name in full 22/11/2011 Date Copyright © 2011 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract Integrating the poor into the fibre of the city is an important theme in housing and urban policies in post‐apartheid South Africa. In other words, the need for making place for the ‘black’ majority in urban spaces previously reserved for ‘whites’ is premised on notions of equity and social change in a democratic political dispensation. However, these potentially transformative thrusts have been eclipsed by more conservative, neoliberal developmental trajectories. Failure to transform apartheid spatialities has worsened income distribution, intensified suburban sprawl, and increased the daily livelihood costs of the poor. After a decade of unintended consequences, new policy directives on informal settlements were initiated through Breaking New Ground (DoH 2004b). -

Public Libraries in the Free State

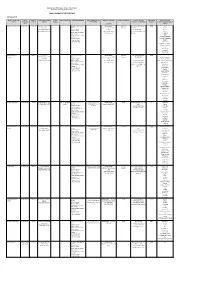

Department of Sport, Arts, Culture & Recreation Directorate Library and Archive Services PUBLIC LIBRARIES IN THE FREE STATE MOTHEO DISTRICT NAME OF FRONTLINE TYPE OF LEVEL OF TOWN/STREET/STREET STAND GPS COORDINATES SERVICES RENDERED SPECIAL SERVICES AND SERVICE STANDARDS POPULATION SERVED CONTACT DETAILS REGISTERED PERIODICALS AND OFFICE FRONTLINE SERVICE NUMBER NUMBER PROGRAMMES CENTER/OFFICE MANAGER MEMBERS NEWSPAPERS AVAILABLE IN OFFICE LIBRARY: (CHARTER) Bainsvlei Public Library Public Library Library Boerneef Street, P O Information and Reference Library hours: 446 142 Ms K Niewoudt Tel: (051) 5525 Car SA Box 37352, Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 446-3180 Fair Lady LANGENHOVENPARK, Outreach Services 17:00 Fax: (051) 446-1997 Finesse BLOEMFONTEIN, 9330 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 karien.nieuwoudt@mangau Hoezit Government Info Services Sat: 8:30-12:00 ng.co.za Huisgenoot Study Facilities Prescribed books of tertiary Idees Institutions Landbouweekblad Computer Services: National Geographic Internet Access Rapport Word Processing Rooi Rose SA Garden and Home SA Sports Illustrated Sarie The New Age Volksblad Your Family Bloemfontein City Public Library Library c/o 64 Charles Information and Reference Library hours: 443 142 Ms Mpumie Mnyanda 6489 Library Street/West Burger St, P Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 051 405 8583 Africa Geographic O Box 1029, Outreach Services 17:00 Architect and Builder BLOEMFONTEIN, 9300 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 Tel: (051) 405-8583 Better Homes and Garden n Government Info -

Fact Finder 2011

TABLe Of cOntentS Welcoming message: Prof Cheryl de la Rey 3 University of Pretoria campuses and faculties 4 Contact information and banking details 6 Important dates 9 Facts A-Z (in alphabetical order) Academic records 12 Accommodation 12 Accounts 13 Admission and registration (first-year students) 14 Bookshops 15 Bursary and loans division (financial aid) 16 Career Placement Centre/job opportunities 18 Cashiers 19 Computer facilities 19 Crisis Service (24 hour) 20 Dining on campus 20 Disbursements 21 Discontinuation of studies/modules and changing of academic programme 21 Emergency University of Pretoria telephone numbers 22 Emotional and academic support 22 Examinations 23 Fees 25 Health services 26 HIV and AIDS counselling 27 International students 28 Internet access 29 Language policy and medium of instruction 30 Legal aid 30 Letter confirming full-time studies 32 Letter of proof of residence 32 Letter for students travelling abroad 32 Library Services 32 Lost and found 35 Museums, heritage collections and galleries 35 Parking 35 fact finder 1 Facts A-Z (in alphabetical order) Page Performing arts 37 Plagiarism 38 Printing and copying services 39 Proof of registration 39 Radio station 40 Programme for registration and start of the academic year (29 January to 11 February) 40 Registration process (all students) 41 Safety and security 46 Safety routes (the Green Route) 46 Sport 47 Student access cards 49 Student affairs 49 Student Representative Council (SRC) 51 Student online services 51 Study methods and study advice 52 Transport/bus services 53 Unit for Students with Special Needs 53 Disciplinary Code: Students 55 ISBN 978-1-86854-802-6 2 fact finder WeLcOme tO the UniverSity Of PretOria A welcoming message from the Vice-Chancellor and Principal Dear student and prospective student, Welcome to the University of Pretoria, one of the leading universities in South Africa that is recognised internationally. -

Good Hope FM Rebranding

SOUTH AFRICAN BROADCASTING SABC SOC LIMITED (“the SABC”) REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL (RFP) RFP NUMBER: RFP/RAD/2020/48 RFP TITLE: GOOD HOPE FM REBRANDING CAMPAIGN EXPECTED TIMEFRAME BID PROCESS EXPECTED DATES Bid Advertisement Date 30 October 2020 National Treasury’s tender portal (http://www.etenders.gov.za) Bid Documents Available From SABC Website (http://www.sabc.co.za/sabc/tenders/) Briefing Session Date and Time The Bid Specification Committee (BSC) to Virtual Briefing Session make use of virtual Briefing sessions were Briefing Session is deemed necessary and cannot be avoided. Date: 11 November 2020 AT 11H00 See Annexure A (Guideline for Briefing Session) that the bidder needs to take note of Microsoft Teams meeting Join on your computer or mobile app Venue/ Link for virtual Briefing session Click here to join the meeting Learn More | Meeting options Bid Closing Date and Time 20 November 2020 @ 12:00 noon Contact details [email protected] The SABC retains the right to change the timeframe whenever necessary and for whatever reason it deems fit. BIDS DELIVERY SABC's Tender Box SABC Office Radio Park Henley Road; Auckland Johannesburg Confidential and Proprietary Information Page 1 of 48 Bid Document During the COVID-19 pandemic, bidders may submit bids in the tender box or electronically until further notice. Refer to Document A for Conditions to be observed when bidding. Late Bid submissions will not be accepted for consideration by the SABC. Confidential and Proprietary Information Page 2 of 48 Bid Document RFP NUMBER: RFP/RAD/2020/48 RFP TITLE: Good Hope FM Rebranding Campaign 1. -

Human Rights, Civil Society & the Media in Sub-Saharan Africa

Media Human rights Civil society Coalition Partnership Sustainable media Media Human rights Civil society Coalition Partnership Sustainable media Media Human rights Civil society Coalition Partnership Sustainable media Media Human rights Civil society Coalition Partnership Sustainable media Media Human rights Civil society Coalition Partnership Sustainable media Media Human rights Civil society Coalition Partnership Sustainable media Media Human rights Civil society Coalition Partnership Sustainable media Media Human rights Civil society Coalition Partnership Sustainable media Media Human rights Civil society Coalition Partnership Sustainable media Media Human rights Civil society Coalition Partnership Sustainable media Media Human rights Civil society Coalition Partnership Sustainable media Media Human rights Civil society Coalition Partnership Sustainable media Media Human rights Civil society Coalition Partnership Sustainable media Media Human rights Civil society Coalition Media Human rights Civil society Coalition Partnership Sustainable media Media Human rights Civil society Coalition Partnership Sustainable media Media Human rights Civil society Coalition Partnership Sustainable media Media Human rights Civil society Coalition Partnership Sustainable media Media Human rights Civil society Coalition Partnership Sustainable media Media Human rights Civil society Coalition Partnership Sustainable media Media Human rights Civil society Coalition Partnership Sustainable media Media Human rights Civil society Coalition Partnership Sustainable -

Participant Biographies

Participant Biographies African Regional Conference on the Right of Access to Information Accra, Ghana February 7-9, 2010 Samuel O. Ablakwa Gbenga Adefaye Estelle Akofio-Sowah Currently the Country Lead of Google Ghana, Estelle is a highly motivated individual, committed to the social and economic development of Ghana. Previously the Managing Director of BusyInternet, Africa's hugely successful internet startup, highlights of her leadership there include launching an ISP which went on to be awarded ISP of the year 2008, winning a World Bank Incubator SME program grant and successfully raising the finances required to open two additional cafe outlets serving an average of 1000 clients per day. In 2008, Estelle was awarded Top African ICT Business Woman by the ForgeAhead African ICT Achievers Award Program in South Africa. A 2008 Class Fellow of the West African Leadership initiative (Aspen, Colorado), Estelle has a degree in Economics and Development Studies from the University of Sussex. Other work experience includes being the Conference and Banqueting Manager at La-Palm Royal Beach Hotel (Ghana’s only 5-star hotel) and Project Manager of the National Poverty Reduction Program at ProNet (local NGO partner to WaterAid UK). From her twelve years work experience in Ghana, Estelle has a broad understanding of local conditions, politics, social dynamics and the ICT community. Anthony Akoto Ampaw Joseph Allan Elizabeth Alpha-Lavalie Elizabeth Alpha - Lavalie is a professional Banker turned politician. She was elected to parliament in 1996 and served as Chairperson of the Finance committee and the committee of Health and Social services. She was elected Deputy Speaker of the Sierra Leone Parliament in 2001 and served as Chairperson of the Public Accounts Committee. -

Office of the Western Cape Police Ombudsman

Office of the Western Cape Police Ombudsman Annual Report 2014-15 Western Cape Police Ombudsman 1 Annual Report 2014-15 Office of the Western Cape Police Ombudsman Annual Report 2014-15 CONTENTS PART A: GENERAL INFORMATION ……………………………………………….............……………… 3 1. Departmental General Information ………………………………….......................………………………………..... 4 2. List of Abbreviations ……………………………………………………….…................................………………………… 5 3. Foreword by Ombudsman …………………………………………….…..........................……………………………….. 6 4. Strategic Overview ………………………………………………………….….............................……………………………. 8 4.1 Vision …………………………………………………………………….........................……………………………….. 8 4.2 Mission …………………………………………………………………........................………………………………… 8 4.3 Values ……………………………………………………………………….........................……………………………. 8 4.4 Summary ……………………………………………………………………............................……………………….. 9 5. Legislative and other Mandates ………………………………………………….........................……………………… 11 6. The Complaint Resolution Process ……………………………………………………………..........................…….. 13 7. Organisational Structure ……………………………………………………………………………........................……… 17 PART B: PERFORMANCE INFORMATION ……………………………………….........…..………….. 19 1. Overview of WCPO Performance ………………..……………………………………………….............................… 20 1.1 Service Delivery Environment ………………………………………………………………...............……….. 20 1.2 Formation of Task Team ……………………………………………………………………….......................… 23 1.3 Best Practice Benchmarking