Prison Conditions in Indonesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reconnaissance Study Of

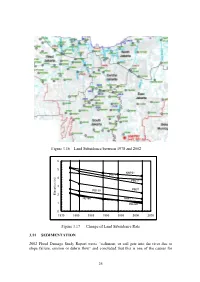

Figure 3.16 Land Subsidence between 1978 and 2002 6 5 NWP21 PB71 4 PB217 3 PB189 PB37 Elevation (m) Elevation 2 PB166 NWP17 1 PB384 0 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 Figure 3.17 Change of Land Subsidence Rate 3.11 SEDIMENTATION 2002 Flood Damage Study Report wrote “sediment, or soil gets into the river due to slope failure, erosion or debris flow” and concluded that this is one of the causes for 25 devastation of river flow capacity. However, trace of slope failure or debris flow cannot be found, though the study team conducted a field reconnaissance survey. The team found sheet erosion at the wide subdivisions/resorts of Village (Desa) Hambarang, parts of which are still under construction and also conversion areas of forest to vegetable field at Village Gunung Geulis. But, it is judged that sediment volume eroded from these areas cannot aggradate river bed in consideration of its volume, though river water contains wash load, most of which is transported to the Java Sea without deposition. 3.12 SURVEY ON SOCIO-ECONOMIC AND CULTURAL ENVIRONMENT A survey was conducted through interview to inhabitants so as to collect information on socio-economic and culture environment of inhabitants and informal dwellers in three (3) flood prone areas in DKI Jakarta, namely 1) South Jakarta (Tebet District, Manggarai Sub-district), 2) Central Jakarta (Kemayoran District, Serdang Sub-district) and 3) North Jakarta (Penjaringan District, Penjaringan Sub-disctict) as shown in Figure 3.18. Kelurahan Serdang Kec. Kemayoran Jakarta Pusat Kelurahan Pluit/Penjaringan Kec. Penjaringan Jakarta Utara LEGEND : Kelurahan Mangarai River Kec. -

Calling for Truth About Mass Killings of 1965/6

Calling for truth about mass killings of 1965/6 Civil Society Initiatives in revealing the truth of mass killings of 1965/6 under the transitional justice framework in Indonesia Candidate number: 9006 Submission deadline: 15 August 2014 Number of words: 19,996 Table of contents Abstract ………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Abbreviation and Names ……………………………………………………………….. 2 CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………. 5 1. 1. Background ……………………………………………………………….. 5 2. 2. Objective, scope and research question …………………………………... 7 3. 3. Methodology ……………………………………………………………… 8 4. 4. Structure …………………………………………………………………. 10 2. THE CONCEPT OF TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE FRAMWORK, RIGHT TO TRUTH AND CIVIL SOCIETY UNDER TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE FRAMEWORK ……………………………………………………………… 12 2. 1. Key concepts of the transitional justice framework …………………… 12 2. 2. Truth seeking and transitional justice ………………………………….. 15 2. 3. Civil society and transitional justice …………………………………….18 3. THE POLITICAL CONTEXT OF MASS KILLINGS OF 1965/6 IN INDONESIA’S POLITICAL TRANSITION …....…………………………20 3. 1. Political transition in Indonesia …………………………………………. 20 3. 2. State denial of the mass killings of 1965/6 ……………………………… 25 4. CIVIL SOCIETY INITIATIVES IN REVEALING THE TRUTH OF MASS KILLINGS OF 1965/6 ………………………………………………. 30 4. 1. Civil society and transitional justice in Indonesia ………………………. 30 4. 2. Civil society organizations’ initiatives in revealing the truth about the I mass killings of 1965/6 through formal mechanisms ……………… …. 32 4. 2. 1. Pushing for a Truth and Reconciliation Commission ……….. 32 4. 2. 2. Pushing for a pro justicia investigation of mass killings of 1965/6 to the National Human Rights Commission ………… 34 4. 3. Civil society organizations initiatives in revealing the truth about the mass killings 1965/6 through informal or unofficial truth mechanisms ……………………………………………………………. 38 4. 3. 1. -

Perancangan Terminal Kampung Melayu Jatinegara, Jakarta Timur

LAPORAN TUGAS AKHIR - RA.141581 AGREGASI: PERANCANGAN TERMINAL KAMPUNG MELAYU JATINEGARA, JAKARTA TIMUR MUHAMMAD NURIL ARDAN 3213100028 DOSEN PEMBIMBING: ANGGER SUKMA M, ST., MT. PROGRAM SARJANA DEPARTEMEN ARSITEKTUR FAKULTAS TEKNIK SIPIL DAN PERENCANAAN INSTITUT TEKNOLOGI SEPULUH NOPEMBER SURABAYA 2017 LAPORAN TUGAS AKHIR - RA.141581 AGREGASI: PERANCANGAN TERMINAL KAMPUNG MELAYU JATINEGARA, JAKARTA TIMUR MUHAMMAD NURIL ARDAN 3213100028 DOSEN PEMBIMBING: ANGGER SUKMA M, ST., MT. PROGRAM SARJANA DEPARTEMEN ARSITEKTUR FAKULTAS TEKNIK SIPIL DAN PERENCANAAN INSTITUT TEKNOLOGI SEPULUH NOPEMBER SURABAYA 2017 FINAL PROJECT REPORT - RA.141581 AGGREGATION: THE DESIGN OF KAMPUNG MELAYU TERMINAL, JATINEGARA, EAST JAKARTA MUHAMMAD NURIL ARDAN 3213100028 TUTOR : ANGGER SUKMA M, ST., MT. UNDERGRADUATE PROGRAM DEPARTEMENT OF ARCHITECTURE FAKULTAS OF CIVIL ENGINEERING AND PLANNING INSTITUT TEKNOLOGI SEPULUH NOPEMBER SURABAYA 2017 ABSTRAK AGREGASI: PERANCANGAN TERMINAL KAMPUNG MELAYU, JATINEGARA, JAKARTA TIMUR Oleh Muhammad Nuril Ardan NRP : 3213100028 Kota dengan segala perkembangannya menarik orang dengan segala etnis, suku dan budayanya untuk hijrah dari desa ke kota. Hal ini menjadikan komposisi kota semakin heterogen dan beragam. Heterogenitas inilah yang kemudian secara tidak langsung menciptakan “batasan” (red. Segregasi) antar kelompok tertentu (dalam hal ini etnis) dalam kawasan perkotaan. dan hal ini pula yang memungkinkan terjadinya konflik perkotaan. Heterogenitas perkotaan perlu di biaskan (red. Agregasi). Agar kota tetap kondusif dengan segala kompleksitasnya. Dengan menggunakan pendekatan ruang dan aktivitas manusia yang beragam karakteristik etnis, diharapakan batasan-batasan tersebut akan terbiaskan. Melalui arsitektur yang berorientasi pada penyelesaian permsalahan sosial, perancangan pasar dan terminal sebagai ruang interaksi di masyarakat menjadi bagian dari respons segregasi. Dengan pendekatan agregasi dan penyelesaian melalui metode hybrid, rancangan arsitektur diupayakan menjadi rancangan yang interaktive dan bermanfaat. -

1 Urban Risk Assessment Jakarta, Indonesia Map City

CITY SNAPSHOT URBAN RISK ASSESSMENT (From Global City Indicators) JAKARTA, INDONESIA Total City Population in yr: 9.6 million in 2010 MAP Population Growth (% annual): 2.6% Land Area (Km2): 651 Km2 Population density (per Km2): 14,465 Country's per capita GDP (US$): $2329 % of country's pop: 4% Total number of households (based on registered Kartu Keluarga): 2,325,973 Administrative map of Jakarta1 Dwelling density (per Km2): N.A. CITY PROFILE GRDP (US$) 10,222 Jakarta is located on the north coast of the island of Java in the Indonesian archipelago in Southeast Asia. It is the country’s largest city and the political and economic hub of % of Country's GDP: 20% Indonesia. The city’s built environment is characterized physically by numerous skyscrapers, concentrated in the central business district but also built ad hoc throughout the city, especially in the past 20 years. The rest of Jakarta generally comprises low‐lying, Total Budget (US$) $3.1 Billion densely populated neighborhoods, which are highly diverse in terms of income levels and uses, and many of these neighborhoods are home to varied informal economic activities. The population of Jakarta is considered wealthy relative to neighboring provinces and Date of last Urban Master Plan: 2010 1 Source: DKI Jakarta 1 other islands, and indeed its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita is more than four times the national average. Jakarta is located in a deltaic plain crisscrossed by 13 natural rivers and more than 1,400 kilometers of man‐ made waterways. About 40% of the city, mainly the area furthest north near the Java Sea, is below sea level. -

{Download PDF} Jakarta: 25 Excursions in and Around the Indonesian Capital Ebook, Epub

JAKARTA: 25 EXCURSIONS IN AND AROUND THE INDONESIAN CAPITAL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Andrew Whitmarsh | 224 pages | 20 Dec 2012 | Tuttle Publishing | 9780804842242 | English | Boston, United States Jakarta: 25 Excursions in and around the Indonesian Capital PDF Book JAKARTA, Indonesia -- A jet carrying 62 people lost contact with air traffic controllers minutes after taking off from Indonesia's capital on a domestic flight on Saturday, and debris found by fishermen was being examined to see if it was from the missing plane, officials said. Bingka Laksa banjar Pekasam Soto banjar. Recently, she spent several months exploring Africa and South Asia. The locals always have a smile on their face and a positive outlook. This means that if you book your accommodation, buy a book or sort your insurance, we earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. US Capitol riots: Tracking the insurrection. The Menteng and Gondangdia sections were formerly fashionable residential areas near the central Medan Merdeka then called Weltevreden. Places to visit:. We'll assume you're ok with this, but you can opt-out if you wish. Some traditional neighbourhoods can, however, be identified. Tis' the Season for Holiday Drinks. What to do there: Eat, sleep, and be merry. Special interest tours include history walks, urban art walks and market walks. Rujak Rujak cingur Sate madura Serundeng Soto madura. In our book, that definitely makes it worth a visit. Jakarta, like any other large city, also has its share of air and noise pollution. We work hard to put out the best backpacker resources on the web, for free! Federal Aviation Administration records indicate the plane that lost contact Saturday was first used by Continental Airlines in Articles from Britannica Encyclopedias for elementary and high school students. -

Nama Sekolah Jumlah Anak Penerima KJP SDN ANCOL 01 PG. 323 SDN ANCOL 03 PG. 210 SDN ANCOL 04 PT. 163 SDN ANGKE 01 PG. 375 SDN AN

Nama Sekolah Jumlah Anak Penerima KJP SD SDN ANCOL 01 PG. 323 SDN ANCOL 03 PG. 210 SDN ANCOL 04 PT. 163 SDN ANGKE 01 PG. 375 SDN ANGKE 03 PG. 72 SDN ANGKE 04 PT. 134 SDN ANGKE 05 PG. 79 SDN ANGKE 06 PG. 238 SDN BALE KAMBANG 01 PG. 138 SDN BALE KAMBANG 03 PG. 171 SDN BALIMESTER 01 PG. 69 SDN BALIMESTER 02 PT. 218 SDN BALIMESTER 03 PT. 274 SDN BALIMESTER 06 PG. 65 SDN BALIMESTER 07 PT. 110 SDN BAMBU APUS 01 PG. 84 SDN BAMBU APUS 02 PG. 92 SDN BAMBU APUS 03 PG. 283 SDN BAMBU APUS 04 PG. 79 SDN BAMBU APUS 05 PG. 89 SDN BANGKA 01 PG. 95 SDN BANGKA 03 PG. 96 SDN BANGKA 05 PG. 60 SDN BANGKA 06 PG. 42 SDN BANGKA 07 PG. 103 SDN BARU 01 PG. 10 SDN BARU 02 PG. 46 SDN BARU 03 PG. 124 SDN BARU 05 PG. 128 SDN BARU 06 PG. 107 SDN BARU 07 PG. 20 SDN BARU 08 PG. 163 SDN BATU AMPAR 01 PG. 24 SDN BATU AMPAR 02 PG. 100 SDN BATU AMPAR 03 PG. 81 SDN BATU AMPAR 05 PG. 61 SDN BATU AMPAR 06 PG. 113 SDN BATU AMPAR 07 PG. 108 SDN BATU AMPAR 08 PG. 66 SDN BATU AMPAR 09 PG. 95 SDN BATU AMPAR 10 PG. 111 SDN BATU AMPAR 11 PG. 91 SDN BATU AMPAR 12 PG. 64 SDN BATU AMPAR 13 PG. 38 SDN BENDUNGAN HILIR 01 PG. 144 SDN BENDUNGAN HILIR 02 PT. 92 SDN BENDUNGAN HILIR 03 PG. -

Situation Report #3 FLOODS in JABODETABEK January 2, 2020

Situation Report #3 FLOODS in JABODETABEK January 2, 2020 Type : Flood Location : Jakarta, Bogor, Tangerang, Bekasi Time : January 2, 2020 I. Keys Information 1. Heavy rain since Tuesday flushed all over Jakarta and surrounding areas until Wednesday morning 2. A total of 268 villages in Jabodetabek were flooded with a height between 30-200 cm. 3. There are 6 areas with a height of water around 2 meters : Cipinang Melayu East Jakarta, Jatikramat Bekasi, Bekasi Exile, Margahayu Bekasi, Duren Jaya Bekasi, and Bintaro South Jakarta. 4. Flood points in DKI Jakarta includes West Jakarta 30 points, Central Jakarta 22 points, South Jakarta 28 points, East Jakarta 65 points, North Jakarta 13 points. 5. Flood points in Bekasi, Depok and Tangerang, among others: Bekasi Regency 47 points, Bogor Regency 11 points, Bekasi City 43 points, Tangerang City 4 points and Tangerang Selatan City 5 points. 6. The number of victims by floods was 16 people : DKI Jakarta 8 people, Bekasi City 1 person, Depok City 3 people, Bogor City 1 person, Bogor Regency 1 person, Tangerang City 1 person and Tangerang Selatan 1 person. 7. The number of refugee in Jakarta are 269 locations with a total refugees 31,232 people. II. Description of Situation Heavy rain since Tuesday, December 31, 2019 flushed all regions in Jakarta and its surroundings until 07.35 am, the rain continued to flush. As a result, a number of areas in Jakarta and surrounding areas were flooded after being rained overnight. The water level at the Katulampa dam is 170 centimeters, rain conditions and alert status number 2. -

Only Yesterday in Jakarta: Property Boom and Consumptive Trends in the Late New Order Metropolitan City

Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 38, No.4, March 2001 Only Yesterday in Jakarta: Property Boom and Consumptive Trends in the Late New Order Metropolitan City ARAI Kenichiro* Abstract The development of the property industry in and around Jakarta during the last decade was really conspicuous. Various skyscrapers, shopping malls, luxurious housing estates, condominiums, hotels and golf courses have significantly changed both the outlook and the spatial order of the metropolitan area. Behind the development was the government's policy of deregulation, which encouraged the active involvement of the private sector in urban development. The change was accompanied by various consumptive trends such as the golf and cafe boom, shopping in gor geous shopping centers, and so on. The dominant values of ruling elites became extremely con sumptive, and this had a pervasive influence on general society. In line with this change, the emergence of a middle class attracted the attention of many observers. The salient feature of this new "middle class" was their consumptive lifestyle that parallels that of middle class as in developed countries. Thus it was the various new consumer goods and services mentioned above, and the new places of consumption that made their presence visible. After widespread land speculation and enormous oversupply of property products, the property boom turned to bust, leaving massive non-performing loans. Although the boom was not sustainable and it largely alienated urban lower strata, the boom and resulting bust represented one of the most dynamic aspect of the late New Order Indonesian society. I Introduction In 1998, Indonesia's "New Order" ended. -

Sudargo Gautama and the Development of Indonesian Public Order: a Study on the Application of Public Order Doctrine in a Pluralistic Legal System

Sudargo Gautama and the Development of Indonesian Public Order: A Study on the Application of Public Order Doctrine in a Pluralistic Legal System Yu Un Oppusunggu A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: John O. Haley, Chair Michael E. Townsend Beth E. Rivin Program Authorized to Offer Degree School of Law © Copyright 2015 Yu Un Oppusunggu ii University of Washington Abstract Sudargo Gautama and the Development of Indonesian Public Order: A Study on the Application of Public Order Doctrine in a Pluralistic Legal System Yu Un Oppusunggu Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor John O. Haley School of Law A sweeping proviso that protects basic or fundamental interests of a legal system is known in various names – ordre public, public policy, public order, government’s interest or Vorbehaltklausel. This study focuses on the concept of Indonesian public order in private international law. It argues that Indonesia has extraordinary layers of pluralism with respect to its people, statehood and law. Indonesian history is filled with the pursuit of nationhood while protecting diversity. The legal system has been the unifying instrument for the nation. However the selected cases on public order show that the legal system still lacks in coherence. Indonesian courts have treated public order argument inconsistently. A prima facie observation may find Indonesian public order unintelligible, and the courts have gained notoriety for it. This study proposes a different perspective. It sees public order in light of Indonesia’s legal pluralism and the stages of legal development. -

Kode Dan Data Wilayah Administrasi Pemerintahan Provinsi Dki Jakarta

KODE DAN DATA WILAYAH ADMINISTRASI PEMERINTAHAN PROVINSI DKI JAKARTA JUMLAH N A M A / J U M L A H LUAS JUMLAH NAMA PROVINSI / K O D E WILAYAH PENDUDUK K E T E R A N G A N (Jiwa) **) KABUPATEN / KOTA KAB KOTA KECAMATAN KELURAHAN D E S A (Km2) 31 DKI JAKARTA 31.01 1 KAB. ADM. KEP. SERIBU 2 6 - 10,18 21.018 31.01.01 1 Kepulauan Seribu 3 - Utara 31.01.01.1001 1 Pulau Panggang 31.01.01.1002 2 Pulau Kelapa 31.01.01.1003 3 Pulau Harapan 31.01.02 2 Kepulauan Seribu 3 - Selatan. 31.01.02.1001 1 Pulau Tidung 31.01.02.1002 2 Pulau Pari 31.01.02.1003 3 Pulau Untung Jawa 31.71 2 KODYA JAKARTA PUSAT 8 44 - 52,38 792.407 31.71.01 1 Gambir 6 - 31.71.01.1001 1 Gambir 31.71.01.1002 2 Cideng 31.71.01.1003 3 Petojo Utara 31.71.01.1004 4 Petojo Selatan 31.71.01.1005 5 Kebon Pala 31.71.01.1006 6 Duri Pulo 31.71.02 2 Sawah Besar 5 - 31.71.02.1001 1 Pasar Baru 31.71.02.1002 2 Karang Anyar 31.71.02.1003 3 Kartini 31.71.02.1004 4 Gunung Sahari Utara 31.71.02.1005 5 Mangga Dua Selatan 31.71.03 3 Kemayoran 8 - 31.71.03.1001 1 Kemayoran 31.71.03.1002 2 Kebon Kosong 31.71.03.1003 3 Harapan Mulia 31.71.03.1004 4 Serdang 1 N A M A / J U M L A H LUAS JUMLAH NAMA PROVINSI / JUMLAH WILAYAH PENDUDUK K E T E R A N G A N K O D E KABUPATEN / KOTA KAB KOTA KECAMATAN KELURAHAN D E S A (Km2) (Jiwa) **) 31.71.03.1005 5 Gunung Sahari Selatan 31.71.03.1006 6 Cempaka Baru 31.71.03.1007 7 Sumur Batu 31.71.03.1008 8 Utan Panjang 31.71.04 4 Senen 6 - 31.71.04.1001 1 Senen 31.71.04.1002 2 Kenari 31.71.04.1003 3 Paseban 31.71.04.1004 4 Kramat 31.71.04.1005 5 Kwitang 31.71.04.1006 6 Bungur -

Mahkamah Agu Mahkamah Agung

Direktori Putusan Mahkamah Agung Republik Indonesia putusan.mahkamahagung.go.id PUTUSAN Nomor 275/PDT/2016/PT.DKI DEMI KEADILAN BERDASARKAN KETUHANAN YANG MAHA ESA Mahkamah AgungPengadilan Tinggi Jakarta Republik yang memeriksa dan memutus perkaraIndonesia perdata pada tingkat banding, telah menjatuhkan putusan sebagai berikut dalam perkara antara : 1. AIDA SASKIA, bertempat tinggal di Jalan Lembang No. 67 RT.011/ RW.007, Kelurahan Menteng, Kecamatan Menteng, Jakarta Pusat, selanjutnya disebut sebagai TERGUGAT ; 2. ASHAR DARIUS, bertempat tinggal di Jalan Tongkol II D-13/14 P.Permai RT.06/RW.03, Kelurahan Kuta Baru, Kecamatan Pasar Kemis, Tangerang, selanjutnya disebut sebagai TURUT TERGUGAT I; 3. ANNA JESSICA, bertempat tinggal di Jalan Lembang No. 67 RT.011/ RW.007, Kelurahan Menteng, Kecamatan Menteng, Jakarta Pusat, selanjutnya disebut sebagai TURUT TERGUGAT II; 4. MUHAMAD ANAS MALLA, bertempat tinggal di Jalan Graha Taman Blok HC 10 No. 1A Bintaro Sektor 9 Tangerang Selatan, selanjutnya disebut sebagai TURUT TERGUGAT III; Mahkamah AgungDalam hal ini diwakili Republikoleh Kuasa Hukumnya : IWAN IndonesiaSETIAWAN, SH.,MM., dan NURIATY SITOMPUL, SH., Para Advokat pada Kantor Hukum MOSS & ASSOCIATE, beralamat di Patria Apartement & Office, Jalan Mayjen. D.l. Panjaitan Kav 5-7, room 1607 Jakarta Timur, berdasarkan Surat Kuasa Khusus tertanggal 25 Nopember 2015 selanjutnya disebut PEMBANDING semula TERGUGAT dan PARA TURUT TERGUGAT; M E LAWAN: 1. JAMES ROBERT HURKENS, bertempat tinggal di Jalan AUP RT.006/ RW.010, Kelurahan Pasar Minggu, Kecamatan Pasar Minggu, Jakarta Selatan, selanjutnya disebut sebagai............................................................ PENGGUGAT I; 2. DONNA GABY HURKENS, bertempat tinggal di Jalan AUP RT.006/ RW.010, Kelurahan Pasar Minggu, Kecamatan Pasar Minggu, Jakarta Selatan, selanjutnya disebut sebagai........................................................... -

Title of the Document

Underage drivers rule the road by night “It’s not that hard once you’ve got it moving,” says Andi Ilham as he powers a lurching Metro Mini at high speed down a Jakarta street late at night. The No. 75 bus that he drives most nights, plying the popular route between Blok M and Pasar Minggu in South Jakarta, is one of a fleet of 13 that belongs to a distant relative, through whom Andi got the job. He says he started out as a conductor on one of the Metro Minis, and gradually learned how to drive the heavy, smoke-belching bus. Neatly dressed in a button-down checked shirt and jeans, and wearing closed shoes, Andi is not your typical Metro Mini driver. That’s because he’s only 16 years old. Too young to apply for a driver’s license or even an ID card — the minimum age for both is 17 — Andi has been driving Metro Minis since he was 15. He claims to be one of a growing number of underage sopir tembak — illegal drivers who fill in for the regular drivers, usually at night, when the streets are less crowded and the police not as likely to pull buses over for traffic infractions. While no government figures are available, the claim may hold water. When the Jakarta Globe visited Blok M, Senen and Manggarai bus terminals over several nights last week, many of the Metro Mini and Kopaja drivers admitted to being between 14 and 17 years old. These drivers, none of whom had a license, operate buses serving some of the most frequented routes, including Blok M to Ciledug, Manggarai to Pasar Minggu and Senen to Lebak Bulus.