An Empirical Investigation of High-Frequency Ground Wave Propagation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

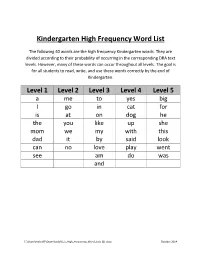

Kindergarten High Frequency Word List

Kindergarten High Frequency Word List The following 40 words are the high frequency Kindergarten words. They are divided according to their probability of occurring in the corresponding DRA text levels. However, many of these words can occur throughout all levels. The goal is for all students to read, write, and use these words correctly by the end of Kindergarten. Level 1 Level 2 Level 3 Level 4 Level 5 a me to yes big I go in cat for is at on dog he the you like up she mom we my with this dad it by said look can no love play went see am do was and C:\Users\metcalfr\Downloads\K_5_High_Frequency_Word_Lists (2).docx October 2014 First Grade High Frequency Word list The goal is for all students to read, write, and use these words (and words from the kindergarten word list) correctly by the end of first grade. after have please all her saw an here should are him so as his some be I’m thank because if that but into them came just then come know they could little there day make us did many very end new want from not were get of what goes one when going or where good our who had out will has over would your C:\Users\metcalfr\Downloads\K_5_High_Frequency_Word_Lists (2).docx October 2014 Second Grade High Frequency Word List The goal is for all students to read, write, and use these words (and the words from preceding grade level word lists) correctly by the end of second grade. -

High Frequency Communications – an Introductory Overview

High Frequency Communications – An Introductory Overview - Who, What, and Why? 13 August, 2012 Abstract: Over the past 60+ years the use and interest in the High Frequency (HF -> covers 1.8 – 30 MHz) band as a means to provide reliable global communications has come and gone based on the wide availability of the Internet, SATCOM communications, as well as various physical factors that impact HF propagation. As such, many people have forgotten that the HF band can be used to support point to point or even networked connectivity over 10’s to 1000’s of miles using a minimal set of infrastructure. This presentation provides a brief overview of HF, HF Communications, introduces its primary capabilities and potential applications, discusses tools which can be used to predict HF system performance, discusses key challenges when implementing HF systems, introduces Automatic Link Establishment (ALE) as a means of automating many HF systems, and lastly, where HF standards and capabilities are headed. Course Level: Entry Level with some medium complexity topics Agenda • HF Communications – Quick Summary • How does HF Propagation work? • HF - Who uses it? • HF Comms Standards – ALE and Others • HF Equipment - Who Makes it? • HF Comms System Design Considerations – General HF Radio System Block Diagram – HF Noise and Link Budgets – HF Propagation Prediction Tools – HF Antennas • Communications and Other Problems with HF Solutions • Summary and Conclusion • I‟d like to learn more = “Critical Point” 15-Aug-12 I Love HF, just about On the other hand… anybody can operate it! ? ? ? ? 15-Aug-12 HF Communications – Quick pretest • How does HF Communications work? a. -

High-Frequency Radiowa Ve Probing of the High-Latitude Ionosphere

RAYMOND A. GREENWALD HIGH-FREQUENCY RADIOWAVE PROBING OF THE HIGH-LATITUDE IONOSPHERE During the past several years, a program of high-frequency radiowave studies of the high-latitude ionosphere has been developed in the APL Space Department. Studies are now being conducted on the formation and motion of high-latitude ionospheric electron density irregularities, using a sophisti cated high-frequency radar system installed at Goose Bay, .Labrador. The radar antenna is also being used to receive signals from a beacon transmitter located at Thule, Greenland. This information is providing a better understanding of the spatial and temporal variability of high-latitude propagation channels and their relationship to disturbances in the magnetosphere-ionosphere system . INTRODUCTION turbances prior to their impingement on the magneto At altitudes above 100 kilometers, the atmosphere sphere is quite limited. Therefore, we still have only of the earth gradually changes from a predominantly limited success in forecasting sudden changes in the neutral medium to an increasingly ionized gas or plas high-latitude ionosphere and consequently in high ma. The ionization is caused chiefly by a combination latitude radiowave propagation. of solar extreme ultraviolet radiation and, at high lati In order for space scientists to obtain a better un tudes, particle precipitation from the earth's magne derstanding of the various interactions occurring tosphere. Because of its ionized nature between 100 among the solar wind, the magnetosphere, and the ion and 1000 kilometers, this part of the atmosphere is osphere, active measurement programs are conduct commonly referred to as the ionosphere. In this re ed in all three regions. -

UNIT -1 Microwave Spectrum and Bands-Characteristics Of

UNIT -1 Microwave spectrum and bands-characteristics of microwaves-a typical microwave system. Traditional, industrial and biomedical applications of microwaves. Microwave hazards.S-matrix – significance, formulation and properties.S-matrix representation of a multi port network, S-matrix of a two port network with mismatched load. 1.1 INTRODUCTION Microwaves are electromagnetic waves (EM) with wavelengths ranging from 10cm to 1mm. The corresponding frequency range is 30Ghz (=109 Hz) to 300Ghz (=1011 Hz) . This means microwave frequencies are upto infrared and visible-light regions. The microwaves frequencies span the following three major bands at the highest end of RF spectrum. i) Ultra high frequency (UHF) 0.3 to 3 Ghz ii) Super high frequency (SHF) 3 to 30 Ghz iii) Extra high frequency (EHF) 30 to 300 Ghz Most application of microwave technology make use of frequencies in the 1 to 40 Ghz range. During world war II , microwave engineering became a very essential consideration for the development of high resolution radars capable of detecting and locating enemy planes and ships through a Narrow beam of EM energy. The common characteristics of microwave device are the negative resistance that can be used for microwave oscillation and amplification. Fig 1.1 Electromagnetic spectrum 1.2 MICROWAVE SYSTEM A microwave system normally consists of a transmitter subsystems, including a microwave oscillator, wave guides and a transmitting antenna, and a receiver subsystem that includes a receiving antenna, transmission line or wave guide, a microwave amplifier, and a receiver. Reflex Klystron, gunn diode, Traveling wave tube, and magnetron are used as a microwave sources. -

HF Radio Propagation

Introduction to HF Radio Propagation 1. The Ionosphere 1.1 The Regions of the Ionosphere In a region extending from a height of about 50 km to over 500 km, most of the molecules of the atmosphere are ionised by radiation from the Sun. This region is called the ionosphere (see Figure 1.1). Ionisation is the process in which electrons, which are negatively charged, are removed from neutral atoms or molecules to leave positively charged ions and free electrons. It is the ions that give their name to the ionosphere, but it is the much lighter and more freely moving electrons which are important in terms of HF (high frequency) radio propagation. The free electrons in the ionosphere cause HF radio waves to be refracted (bent) and eventually reflected back to earth. The greater the density of electrons, the higher the frequencies that can be reflected. During the day there may be four regions present called the D, E, F1 and F2 regions. Their approximate height ranges are: • D region 50 to 90 km; • E region 90 to 140 km; • F1 region 140 to 210 km; • F2 region over 210 km. At certain times during the solar cycle the F1 region may not be distinct from the F2 region with the two merging to form an F region. At night the D, E and F1 regions become very much depleted of free electrons, leaving only the F2 region available for communications. Only the E, F1 and F2 regions refract HF waves. The D region is very important though, because while it does not refract HF radio waves, it does absorb or attenuate them (see Section 1.5). -

International High Frequency Broadcasting Agreement (Mexico

This electronic version (PDF) was scanned by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Library & Archives Service from an original paper document in the ITU Library & Archives collections. La présente version électronique (PDF) a été numérisée par le Service de la bibliothèque et des archives de l'Union internationale des télécommunications (UIT) à partir d'un document papier original des collections de ce service. Esta versión electrónica (PDF) ha sido escaneada por el Servicio de Biblioteca y Archivos de la Unión Internacional de Telecomunicaciones (UIT) a partir de un documento impreso original de las colecciones del Servicio de Biblioteca y Archivos de la UIT. (ITU) ﻟﻼﺗﺼﺎﻻﺕ ﺍﻟﺪﻭﻟﻲ ﺍﻻﺗﺤﺎﺩ ﻓﻲ ﻭﺍﻟﻤﺤﻔﻮﻇﺎﺕ ﺍﻟﻤﻜﺘﺒﺔ ﻗﺴﻢ ﺃﺟﺮﺍﻩ ﺍﻟﻀﻮﺋﻲ ﺑﺎﻟﻤﺴﺢ ﺗﺼﻮﻳﺮ ﻧﺘﺎﺝ (PDF) ﺍﻹﻟﻜﺘﺮﻭﻧﻴﺔ ﺍﻟﻨﺴﺨﺔ ﻫﺬﻩ .ﻭﺍﻟﻤﺤﻔﻮﻇﺎﺕ ﺍﻟﻤﻜﺘﺒﺔ ﻗﺴﻢ ﻓﻲ ﺍﻟﻤﺘﻮﻓﺮﺓ ﺍﻟﻮﺛﺎﺋﻖ ﺿﻤﻦ ﺃﺻﻠﻴﺔ ﻭﺭﻗﻴﺔ ﻭﺛﻴﻘﺔ ﻣﻦ ﻧ ﻘ ﻼً 此电子版(PDF版本)由国际电信联盟(ITU)图书馆和档案室利用存于该处的纸质文件扫描提供。 Настоящий электронный вариант (PDF) был подготовлен в библиотечно-архивной службе Международного союза электросвязи путем сканирования исходного документа в бумажной форме из библиотечно-архивной службы МСЭ. INTERNATIONAL HIGH FREQUENCY BROADCASTING AGREEMENT Mexico City, 1949 FINAL PROTOCOL ANNEXED TO THE INTERNATIONAL HIGH FREQUENCY BROADCASTING AGREEMENT MEXICO CITY PLAN OF THE DISTRIBUTION OF CHANNEL HOURS FOR HIGH FREQUENCY BROADCASTING ANNEXED TO THE INTERNATIONAL HIGH FREQUENCY BROADCASTING AGREEMENT BASi.C_.PL A N INTERNATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATION UNION, G April 1949 Note of the General Secretariat of the I#T,U# The following divergencies were found between the English text of the Mexico City Agreement and the French text which is authoritative: Page 2A. § 5, 3rd line, read: • #••# and, in the Interest of these administrations, ask all administrations ••##.• III# Terms of reference, a), 5th-6th lines, read: This index shall be determined by the T#P#C# Page 31. -

Satellite Communications in the New Space

IEEE COMMUNICATIONS SURVEYS & TUTORIALS (DRAFT) 1 Satellite Communications in the New Space Era: A Survey and Future Challenges Oltjon Kodheli, Eva Lagunas, Nicola Maturo, Shree Krishna Sharma, Bhavani Shankar, Jesus Fabian Mendoza Montoya, Juan Carlos Merlano Duncan, Danilo Spano, Symeon Chatzinotas, Steven Kisseleff, Jorge Querol, Lei Lei, Thang X. Vu, George Goussetis Abstract—Satellite communications (SatComs) have recently This initiative named New Space has spawned a large number entered a period of renewed interest motivated by technological of innovative broadband and earth observation missions all of advances and nurtured through private investment and ventures. which require advances in SatCom systems. The present survey aims at capturing the state of the art in SatComs, while highlighting the most promising open research The purpose of this survey is to describe in a structured topics. Firstly, the main innovation drivers are motivated, such way these technological advances and to highlight the main as new constellation types, on-board processing capabilities, non- research challenges and open issues. In this direction, Section terrestrial networks and space-based data collection/processing. II provides details on the aforementioned developments and Secondly, the most promising applications are described i.e. 5G associated requirements that have spurred SatCom innovation. integration, space communications, Earth observation, aeronauti- cal and maritime tracking and communication. Subsequently, an Subsequently, Section III presents the main applications and in-depth literature review is provided across five axes: i) system use cases which are currently the focus of SatCom research. aspects, ii) air interface, iii) medium access, iv) networking, v) The next four sections describe and classify the latest SatCom testbeds & prototyping. -

Historical Survey of Fading at Medium and High Radio Frequencies

PB161634 *#©. 133 jjoulder laboratories HISTORICAL SURVEY OF FADING AT MEDIUM AND HIGH RADIO FREQUENCIES BY *- ROGER &. SALAIS4AN U. S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS THE NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS Functions and Activities The functions of the National Bureau of Standards are set forth in the Act of Congress, March 3, 1901, as amended by Congress in Public Law 619, 1950. These include the development and maintenance of the na- tional standards of measurement and the provision of means and methods for making measurements consistent with these standards; the determination of physical constants and properties of materials; the development of methods and instruments for testing materials, devices, and structures; advisory services to government agen- cies on scientific and technical problems; invention and development of devices to serve special needs of the Government; and the development of standard practices, codes, and specifications. The work includes basic and applied research, development, engineering, instrumentation, testing, evaluation, calibration services, and various consultation and information services. Research projects are also performed for other government agencies when the work relates to and supplements the basic program of the Bureau or when the Bureau's unique competence is required. The scope of activities is suggested by the listing of divisions and sections on the inside of the back cover. Publications The results of the Bureau's research are published either in the Bureau's own series of publications or in the journals of professional and scientific societies. The Bureau itself publishes three periodicals avail- able from the Government Printing Office: The Journal of Research, published in four separate sections, presents complete scientific and technical papers; the Technical News Bulletin presents summary and pre- liminary reports on work in progress; and Basic Radio Propagation Predictions provides data for determining the best frequencies to use for radio communications throughout the world. -

High Frequency Words

High Frequency Words High-frequency words are the words that appear most often in printed materials. Students are encouraged to recognize these words by sight, without having to “sound them out.” Learning to recognize high-frequency words by sight is critical to developing fluency in reading. Students should be able to read these words individually and in sentences and stories. Automatic recognition of high frequency words provides an essential starting point for your child becoming a confident reader. It is important to note that 12 high frequency words make up 25% of words we read and write. 100 high frequency words make up 50% of words we read and write. about 300 high frequency words account for 75% of words we read and write. Seven Simple Tips to Help Your Child Learn High-Frequency Words 1. Write high-frequency words on index cards. Click on the grade levels below for printable word cards. a. PreK word cards b. Kindergarten cards c. First Grade cards d. Second Grade cards e. Third Grade cards 2. Help your child create sentences with the index cards. (ex. Look at me. I like red.) 3. Have your child say or write sentences using each word. 4. Have your child write the words in shaving cream, play dough, sand, or sugar. 5. Add movement when reading or spelling the words. For example, if the word is look, your child says look three times while jumping, clapping, stomping, or snapping fingers. 6. Read a story to your child. After reading, have him/her find the high frequency words on each page. -

Fading Correlation Bandwidth and Short-Term Frequency Stability Measurements on a High-Frequency Transauroral Path

*>Uo„al Bureau of standard library, ». w . Bldg FEB 4 1963 ^ecknical v2©te 165 FADING CORRELATION BANDWIDTH AND SHORT-TERM FREQUENCY STABILITY MEASUREMENTS ON A HIGH-FREQUENCY TRANSAURORAL PATH J. L. AUTERMAN U. S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS THE NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS Functions and Activities The functions of the National Bureau of Standards are set forth in the Act of Congress, March 3, 1901, as amended by Congress in Public Law 619, 1950. These include the development and maintenance of the na- tional standards of measurement and the provision of means and methods for making measurements consistent with these standards; the determination of physical constants and properties of materials; the development of methods and instruments for testing materials,- devices, and structures; advisory services to government agen- cies on scientific and technical problems; invention and development of devices to serve special needs of the Government; and the development of standard practices, codes, and specifications. The work includes basic and applied research, development, engineering, instrumentation, testing, evaluation, calibration services, and various consultation and information services. Research projects are also performed for other government agencies when the work relates to and supplements the basic program of the Bureau or when the Bureau's unique competence is required. The scope of activities is suggested by the listing of divisions and sections on the inside of the back cover. Publications The results -

Introduction to Wireless Electromagnetic Channels & Large

EE-546 Wireless Communication Technologies Spring 2005 Introduction to Wireless Electromagnetic Channels & Large Scale Fading* Rahul N. Pupala [email protected] Department of Electrical Engineering – Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ 08854 Abstract- This article provides a brief introduction to atmosphere reflects, absorbs or scatters radio waves. wireless channels – frequency range classification of the The layers most relevant to terrestrial radio propagation electromagnetic spectra and large-scale propagation in are shown in fig 1 below. such channels. I. INTRODUCTION/MOTIVATION The term wireless communication refers to the transfer of information using electromagnetic (EM) or acoustic waves over the atmosphere rather than using any propagation medium that employs wires. Not requiring an explicit network of wires and permitting communication while on the move were the main factors which motivated the study of wireless th communication in the early 20 century. Wireless communication evolved remarkably since Fig 1: Atmospheric Layers relevant to terrestrial radio Marconi first demonstrated radio’s ability to provide propagation. continuous contact with ships sailing the English Channel in 1897. Since then, particularly during the last The troposphere is the first layer above the surface decade, the mobile radio communications industry has of the earth, and contains approximately half of the grown by orders of magnitude fueled by digital and RF earth’s atmosphere. This is the layer at which weather circuit fabrication and miniaturization techniques that takes place. The ionosphere is where ions and electrons make portable radio equipment smaller, cheaper and exist in sufficient quantities to reflect and/or refract the more reliable. Digital switching techniques have radio waves. -

A Double-Edged Sword Be Smart When You Design a Climate Room

BY THEO TEKSTRA, MARKETING MANAGER GAVITA HOLLAND EMI CAN DISRUPT OR DEGRADE THE FUNCTIONING OF OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES E.M.I. A DOUBLE-EDGED SWORD BE SMART WHEN YOU DESIGN A CLIMATE ROOM The introduction of high frequency electronic remote ballasts into the market has created a new problem: electromagnetic interference (EMI). EMI consists of high frequency signals which are either conducted (through for example your power cord back to the grid), or emitted in the form of radio waves (for example by your lamp cord connecting a high frequency remote ballast to the lamp). EMI can disrupt or degrade the functioning of other electronic devices. In some cases, this may even lead to life threatening situations, for example, if medical systems or emergency communication systems are influenced. So what is that EMI, and what can we do to avoid it? What are the rules and regulations? 74 E.M.I. I GARDEN CULTURE Standards Let’s get the dull stuff out of the way first: there are two classes which define how much EMI a device may emit: a) Class A for industrial use - Conducted EMI travels through the power cord of the b) Class B for residential or medical use device back to the grid, and is distributed over your mains ca- In industrial environments the EMI levels are allowed to be bles. All devices that are plugged into the same mains supply a bit higher. Class B, for residential use, is more strict than will receive this automatically. The interference does not stop the industrial standard. In Europe, as well as North America, at your house though: a complete block of houses or more, class A and B are used, and are connected to the same supply, can very similar.