History of Sugar Maple Decline Introduction Sugar Maple Dectines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Experimental Branch Cooling Increases Foliar Sugar and Anthocyanin Concentrations in Sugar Maple at the End of the Growing Season Paul G

696 NOTE Experimental branch cooling increases foliar sugar and anthocyanin concentrations in sugar maple at the end of the growing season Paul G. Schaberg, Paula F. Murakami, John R. Butnor, and Gary J. Hawley Abstract: Autumnal leaf anthocyanin expression is enhanced following exposure to a variety of environmental stresses and may represent an adaptive benefit of protecting leaves from those stresses, thereby allowing for prolonged sugar and nutrient resorption. Past work has shown that experimentally induced sugar accumulations following branch girdling triggers anthocyanin biosynthesis. We hypothesized that reduced phloem transport at low autumnal temperatures may increase leaf sugar concentrations that stimulate anthocyanin production, resulting in enhanced tree- and landscape-scale color change. We used refrigerant-filled tubing to cool individual branches in a mature sugar maple (Acer saccharum Marsh.) tree to test whether phloem cooling would trigger foliar sugar accumulations and enhance anthocyanin biosynthesis. Cooling increased foliar sucrose, glucose, and fructose concentrations 2- to nearly 10-fold (depending on the specific sugar and sampling date) relative to controls and increased anthocyanin concentrations by approximately the same amount. Correlation analyses indicated a strong and steady positive relationship between anthocyanin and sugar concentrations, which was consistent with a mechanistic link between cooling-induced changes in these constituents. Tested here at the branch level, we propose that low temperature induced -

The Viability of Tree Leaves for Cellulosic Ethanol

The Viability of Tree Leaves for Cellulosic Ethanol. Testing Select Quercus & Acer saccharum species for glucose content through acid & enzyme hydrolysis Ryan Caudill Grove High School 2013-14 Purpose The purpose of this project is to measure the glucose levels in leaves collected from two varieties of sugar maple and two varieties of oak trees to see if they are viable sources for cellulosic ethanol production. The varieties to be tested are: Acer saccharum “Caddo” (Caddo sugar maple) Acer saccharum “Commemoration” (Commemoration sugar maple) Quercus rubra (red oak) Quercus alba (white oak) Hypothesis A. It is hypothesized that the leaves of two sugar maple varieties, Acer saccharum “Caddo” and Acer saccharum “Commemoration” will contain higher levels of glucose than the leaves of the two varieties of Oak, Quercus alba and Quercus rubra. B. It is also hypothesized that the leaves of all varieties chosen will contain enough glucose to be viable sources for cellulosic ethanol production. Background Research Carbon based fuels have been used in past generations and generations to come. Carbon based fuels are a great source of energy this is why they are used as fuels. When these fuels are burned for their energy to be released this will add carbon to the atmosphere, and that’s not a good thing. Carbon is the primary greenhouse gas emitted by human activity. Also Carbon fuels are in a limited supply, they are nonrenewable and they are being used up at a very quick rate. It is important for the introduction of good reliable fuels that can be used on a very large scale. -

Chapter 14 — Syrup

Chapter 14—Syrup Description of the Product Maple trees become dormant in the winter and store food and Its Uses as liquid starches and sugars. In late winter as tempera- tures begin to rise, the trees start to mobilize these stored Maple syrup is a sweetener, famous for its use on sugars, and the sap begins to move up the trunk to the ° ° pancakes and waffles. It is made by boiling the sap of branches. A combination of cold nights (20 F to 32 F) ° ° maple trees until it thickens into sugary, sweet syrup. and warm days (45 F to 55 F) brings on the greatest sap About 30 to 40 gallons of sap are usually needed to make flow. 1 gallon of pure maple syrup. Both sap flow and sweetness are influenced by heredity Pure maple syrup can only be made from the kinds of and environmental factors. Chief among these is a large maples found in North America. While there are native crown with many leaves exposed to sunlight during the maples on other continents, only North American maples growing season for maximum sap and sugar production. have sap with the flavor cursor that creates the taste of Trees whose crowns have diameters greater than 30 feet maple. can produce as much as 100 percent more syrup than those with narrower crowns and can produce sap as much The sugar maple (Acer saccharum), also known as hard as 30 percent sweeter than narrower crowned trees. Sap or rock maple, is by far the species most often tapped for flow is further increased by large stem diameters, which sap production. -

Investigations of the Processes of Discoloration and Decay of Sugar Maple, Acer Saccharum, Associated with Fomes Connatus

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 1971 INVESTIGATIONS OF THE PROCESSES OF DISCOLORATION AND DECAY OF SUGAR MAPLE, ACER SACCHARUM, ASSOCIATED WITH FOMES CONNATUS TERRY ALAN TATTAR Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation TATTAR, TERRY ALAN, "INVESTIGATIONS OF THE PROCESSES OF DISCOLORATION AND DECAY OF SUGAR MAPLE, ACER SACCHARUM, ASSOCIATED WITH FOMES CONNATUS" (1971). Doctoral Dissertations. 944. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/944 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 71-22,411 TATTAR, Terry Alan, 1943- ] INVESTIGATIONS OF THE PROCESSES OF 1 DISCOLORATION AND DECAY OF SUGAR MAPLE, | ACER SACCHARUM, ASSOCIATED WITH FOMES i CONNATUS. | | University of New Hampshire, Ph.D., 1971 f Botany University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED INVESTIGATIONS OF THE PROCESSES OF DISCOLORATION AND DECAY OF SUGAR MAPLE, ACER SACCHAKUM, ASSOCIATED WITH FCMES CONNATUS. by Terry A: Tattar B.A. Northeastern University, 1967 A thesis Submitted to the University of New Hampshire In Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate School Department of Botany June, 1971 This thesis has been examined and approved. Thesis director/ Xvery E. Rich Prof. of Plant ^(thology a R. Marcel Reeves, Assoc. Prof. of Entomology PLEASE NOTE: Some pages have indistinct print. -

Desirable Street Tree List (PDF)

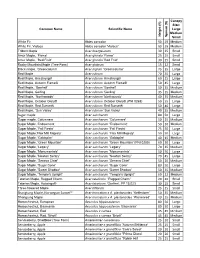

Canopy Size: Common Name Scientific Name Large Medium Height (ft) Spread (ft) Small White Fir Abies concolor 50 25 Medium White Fir, Violaca Abies concolor 'Violaca' 50 25 Medium Trident Maple Acer buergeianum 30 25 Small Amur Maple, `Flame' Acer ginnala` Flame' 25 25 Small Amur Maple, `Red Fruit' Acer ginnala `Red Fruit' 30 25 Small Rocky Mountain Maple (Tree Form) Acer glabrum 15 12 Small Black maple, 'Greencolumn' Acer nigrum 'Greencolumn' 75 35 Large Red Maple Acer rubrum 70 35 Large Red Maple, Armstrong® Acer rubrum Armstrong® 60 25 Large Red Maple, Autumn Flame® Acer rubrum Autumn Flame® 50 45 Large Red Maple, `Bowhall' Acer rubrum ' Bowhall' 50 15 Medium Red Maple, Gerling Acer rubrum 'Gerling' 35 35 Medium Red Maple, `Northwoods' Acer rubrum 'Northwoods ' 40 35 Medium Red Maple, October Glory® Acer rubrum October Glory® (PNI 0268) 50 35 Large Red Maple, Red Sunset® Acer rubrum Red Sunset® 50 40 Large Red Maple, `Sun Valley' Acer rubrum ' Sun Valley' 40 35 Medium Sugar maple Acer saccharum 80 50 Large Sugar maple, Columnare Acer saccharum ' Columnare' 50 25 Medium Sugar Maple, Endowment Acer saccharum ' Endowment' 50 10 Medium Sugar Maple, 'Fall Fiesta' Acer saccharum ' Fall Fiesta' 75 50 Large Sugar Maple,'Flax Mill Majesty' Acer saccharum ' Flax Mill Majesty' 50 50 Large Sugar Maple, 'Goldspire' Acer saccharum ' Goldspire' 40 15 Medium Sugar Maple, 'Green Mountain' Acer saccharum ' Green Mountain' (PNI 0285) 60 30 Large Sugar Maple, 'Legacy' Acer saccharum 'Legacy' 70 35 Medium Sugar Maple, 'Monumentale' Acer saccharum 'Monumentale' -

Maple Syrup Production in Ohio and the Impact of Ohio State University (OSU) Extension Programming

utilization & engineering Maple Syrup Production in Ohio and the Impact of Ohio State University (OSU) Extension Programming Gary W. Graham, P. Charles Goebel, Randall B. Heiligmann, and Matthew S. Bumgardner The maple syrup industry in Ohio, which ranks fifth in total production in the United States, is comprised nink [1985], and Huyler and Williams primarily of small family owned operations that are served by The Ohio State University (OSU) [1992, 1994]), and the genetic improve- Extension system. We evaluated the effectiveness of OSU Extension educational programming designed ment of sugar maple for higher sap sugar to improve sugarbush and sugarhouse management through a survey administered at the three 2004 content (Kriebel 1960, 1989, 1990). Ohio Maple Days workshops. Most survey respondents indicated that after attending past maple syrup workshops they implemented changes that were relatively simple and inexpensive; however, most The Maple Syrup Industry In indicated they are interested in learning more about technologies that increase production and maple Ohio ABSTRACT syrup quality. During the 19th century, Ohio was one of the largest producers of maple syrup Keywords: maple syrup, sugarbush, forest management, Extension (924,000 gal annually), the third largest pro- ducer of maple sugar (614,000 lb annually), and the largest producer of total maple prod- ucts (equivalent to more than a million gal- aple syrup production is a sus- able luxury (Lawrence et al. 1993, Lockhart tainable family forestry activity 2000). lons annually) in the United States (United that has a long tradition in North In many ways, the methods used by States Census Office 1840, 1870, Bryan et M al. -

Acer Saccharum L. Sugar Maple Aceraceae Section Acer, Series Saccharodenron

Acer saccharum L. Sugar Maple Aceraceae Section Acer, series Saccharodenron Introduced to Europe in 1725 Specific epithet: saccharum, with suger [note: this species is different than A. saccharinum, the Silver Maple] Native range: Eastern U.S. Culture: full sun; Sugar Maples appreciate well-drained, moist soils with at least average fertility. They are particularly sensitive to road salt. A medium/large-sized tree to 60’ with an upright, round oval crown. Flowers: pale yellow early spring corymbs Leaves: dark green above, paler beneath glabrous 3-6” across simple, palmate, 3 to 5-lobed, sharply acuminate fall color: brilliant orange and red Fruit: samara (schizocarp) yellowish>brown wings: angle U-shaped each wing 1-1.75” matures Sept.-Oct. Bark: gray; rough, long ridges and plates Twig: smooth and glabrous; green>reddish brown Buds: long, sharply pointed Maintenance: minimal Pruning: minimal Insect and Disease Problems: Landscape Use: Landscape Use: large residential lawns, parks, commercial Wildlife Use: buds, seeds, twigs-squirrels porcupines browse for deer, moose, snowshoe hare Paul Wray, Iowa State University, Bugwood.org Acer saccarum ‘Green Mountain’ © Emily Levine Native Use: Cherokee---infusion of bark for cramps, disentery, hives, eyewash, gynocology, sores Omaha and Winnebago---black dye Visit unlgardens.unl.edu Many tribes used the sap as a sweetener, including Ojibwe, Dakoya, Iroquios, Omaha, and Ponca UNL Gardens Historical/Cultural Information: Maple syrup is a 65 million dollar a year industry in New England And Sugar Maple foliage tourism can be measured in the billion. Acer saccharum Cultivars in Maxwell Arboretum ‘Bonfire’: Princeton Nurseries/J. Frank Schmidt & Son. “vigorous grower with brilliant carmine red autumn color...a selected seedling from open-pollinated seed of A. -

Bigleaf Maple Syrup Nontimber Forest Products for Small Woodland Owners

OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION SERVICE Bigleaf Maple Syrup Nontimber Forest Products For Small Woodland Owners In the Pacific Northwest, sap Spile Drip: Lady DragonflyCC/ CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 BY-NC-SA CC Spile Drip: Lady DragonflyCC/ collection is done in the late fall and winter (after the leaves aple syrup is one of the oldest forms of sweet- have dropped) through early eners, its use dating back hundreds of years. spring prior to bud-break. MMaple syrup comes from maple tree sap, The sap is made up of water, which is collected from living trees and boiled down to dissolved minerals, sugars, the thick, sweet syrup many of us like to pour over our vitamins, and amino acids. It pancakes. moves from the roots of the The sugar maple tree (Acer saccharum) is most com- tree up the stem through the monly used in maple sugaring, but all maples produce sapwood to provide water and sap that can be converted to maple syrup. Though not nutrients to various parts of as high in sugar content as the sugar maple, the sap of the tree. This happens when Bigleaf maple trees. bigleaf maple trees (Acer macrophyllum) grown in the nighttime temperatures are Pacific Northwest produces excellent syrup. In addition at or near freezing. During the day when the tempera- to the delicious flavor, maple sap and syrup are high ture warms, sap flows back down the tree. The sap flow in minerals, such as potassium, calcium, magnesium, quantity and quality will depend on weather conditions, manganese, iron, and zinc, and can boost your energy available moisture, and the soil type. -

The Microbiome of Acer Saccharum: Environmental Drivers of Microbial Communities in Different Plant Structures

UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL THE MICROBIOME OF ACER SACCHARUM: ENVIRONMENTAL DRIVERS OF MICROBIAL COMMUNITIES IN DIFFERENT PLANT STRUCTURES THESIS PRESENTED AS PARTIAL REQUIREMENT OF THE MASTERS OF BIOLOGY BY JESSICA WALLACE AUGUST 2016 UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL Service des bibliothèques Avertissement La diffusion de ce mémoire se fait dans le respect des droits de son auteur, qui a signé le formulaire Autorisation de reproduire et de diffuser un travail de recherche de cycles supérieurs (SDU-522 - Rév.0?-2011 ). Cette autorisation stipule que «conformément à l'article 11 du Règlement no 8 des études de cycles supérieurs, [l 'auteur] concède à l'Université du Québec à Montréal une licence non exclusive d'utilisation et de publication de la totalité ou d'une partie importante de [son] travail de recherche pour des fins pédagogiques et non commerciales. Plus précisément, [l 'auteur] autorise l'Université du Québec à Montréal à reprodu ire , diffuser, prêter, distribuer ou vendre des copies de [son] travail de recherche à des fins non commerciales sur quelque support que ce soit, y compris l'Internet. Cette licence et cette autorisation n'entraînent pas une renonciation de [la] part [de l'auteur] à [ses] droits moraux ni à [ses] droits de propriété intellectuelle. Sauf entente contraire, [l 'auteur] conserve la liberté de diffuser et de commercialiser ou non ce travail dont [il] possède un exemplaire.» UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL LE MICROBIOME D'ACER SACCHARUM: L'INFLUENCE DES FACTEURS ENVIRONNEMENTAUX SUR LES COMMUNAUTÉS MICROBIENNES DES TISSUS VÉGÉTAUX MÉMOIRE PRÉSENTÉE COMME EXIGENCE PARTIELLE DE LA MAÎTRISE EN BIOLOGIE PAR JESSICA WALLACE AOÛT 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ........ -

An Assessment of Stress in Acer Saccharum As a Possible Response to Climate Change

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Fall 2009 An assessment of stress in Acer saccharum as a possible response to climate change Martha Carlson University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Carlson, Martha, "An assessment of stress in Acer saccharum as a possible response to climate change" (2009). Master's Theses and Capstones. 469. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/469 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ASSESSMENT OF STRESS IN ACER SACCHARUM AS A POSSIBLE RESPONSE TO CLIMATE CHANGE BY MARTHA CARLSON BA, MOUNT HOLYOKE COLLEGE, 1968 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fullfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Natural Resources: Environmental Conservation September 2009 UMI Number: 1472053 Copyright 2009 by Carlson, Martha INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Acer Saccharum Sugar Maple1 Edward F

Fact Sheet ST-51 November 1993 Acer saccharum Sugar Maple1 Edward F. Gilman and Dennis G. Watson2 INTRODUCTION Sugar Maple is the most common maple in the east and is a hard-wooded tree with a moderate to slow growth rate (Fig. 1). The tree will be 60 to 80 feet tall at maturity in landscape plantings. Sugar Maple grows about 1 foot each year in most soils but is sensitive to reflected heat, and to drought, turning the leaves brown (scorch) along their edges. Leaf scorch from dry soil is often evident in areas where the root system is restricted to a small soil area, such as a street tree planting. It is more drought-tolerant in open areas where the roots can proliferate into a large soil space. GENERAL INFORMATION Scientific name: Acer saccharum Pronunciation: AY-ser sack-AR-rum Common name(s): Sugar Maple Family: Aceraceae USDA hardiness zones: 3 through 8A (Fig. 2) Origin: native to North America Uses: Bonsai; wide tree lawns (>6 feet wide); screen; shade tree; residential street tree Figure 1. Middle-aged Sugar Maple. Availability: generally available in many areas within its hardiness range Crown shape: oval; round Crown density: dense DESCRIPTION Growth rate: medium Texture: medium Height: 50 to 80 feet Spread: 35 to 50 feet Crown uniformity: symmetrical canopy with a regular (or smooth) outline, and individuals have more or less identical crown forms 1. This document is adapted from Fact Sheet ST-51, a series of the Environmental Horticulture Department, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. -

Sugar Maple Acer Saccharum

Plant Guide England types, while yellows are more pronounced SUGAR MAPLE further west. Interior leaves may be yellow, while outer exposed leaves turn orange-red. The species is Acer saccharum Marsh. Plant Symbol = ACSA3 best suited to larger sites where soil compaction is not a concern. It also is sometimes used in shelterbelt Contributed By: USDA NRCS National Plant Data plantings and has potential value for rehabilitation of Center & the Biota of North America Program disturbed sites. Sugar maple is an important timber tree valued for its hard, heavy, and strong wood, commonly used to make furniture, paneling, flooring, and veneer. It is also used for gunstocks, tool handles, plywood dies, cutting blocks, woodenware, novelty products, sporting goods, bowling pins, and musical instruments. White-tailed deer, moose, and snowshoe hare commonly browse sugar maple. Red squirrel, gray squirrel, and flying squirrels feed on the seeds, buds, twigs, and leaves. Porcupines consume the bark and A.E. Hoyle can girdle the upper stem. Songbirds, woodpeckers, U.S. Forest Service and cavity nesters nest in sugar maple. Although the @ Hunt Institute flowers appear to be wind-pollinated, the early- produced pollen may be important to the biology of Alternate common names bees and other pollen-dependent insects because Hard maple, head maple, sugartree, bird‟s-eye maple many insects, especially bees, visit the flowers. Uses Status Sugar maple is the only tree today used for Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State commercial syrup production, as its sap has twice the Department of Natural Resources for this plant‟s sugar content of other maple species.