Chapter 6. It's Time for a New Forest Fire Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Upper Ovens Environmental FLOWS Assessment

Upper Ovens Environmental FLOWS Assessment * FLOW RECOMMENDATIONS Final 14 December 2006 Upper Ovens Environmental FLOWS Assessment FLOW RECOMMENDATIONS Final 14 December 2006 Sinclair Knight Merz ABN 37 001 024 095 590 Orrong Road, Armadale 3143 PO Box 2500 Malvern VIC 3144 Australia Tel: +61 3 9248 3100 Fax: +61 3 9248 3400 Web: www.skmconsulting.com COPYRIGHT: The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of Sinclair Knight Merz Pty Ltd. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of Sinclair Knight Merz constitutes an infringement of copyright. Error! Unknown document property name. Error! Unknown document property name. FLOW RECOMMENDATIONS Contents 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Structure of report 1 2. Method 2 2.1 Site selection and field assessment 2 2.2 Environmental flow objectives 4 2.3 Hydraulic modelling 4 2.4 Cross section surveys 5 2.5 Deriving flow data 5 2.5.1 Natural and current flows 6 2.6 Calibration 6 2.7 Using the models to develop flow recommendations 7 2.8 Hydraulic output 7 2.9 Hydrology 8 2.10 Developing flow recommendations 10 2.11 Seasonal flows 11 2.12 Ramp rates 12 3. Environmental Flow Recommendations 14 3.1 Reach 1 – Ovens River upstream of Morses Creek 15 3.1.1 Current condition 15 3.1.2 Flow recommendations 15 3.1.3 Comparison of current flows against the recommended flow regime 32 3.2 Reach 2 – Ovens River between Morses Creek and the Buckland River 34 3.2.1 Current condition 34 3.2.2 Flow recommendations 34 3.2.3 Comparison of current flows -

Alpine Shire Rural Land Strategy

Alpine Shire Council Rural Land Strategy – FINAL April 2015 3. Alpine Shire Rural Land Strategy Adopted 7 April 2015 Alpine Shire Council Rural Land Strategy – Final April 2015 1 Contents 1 Contents ....................................................................................................................................................................... 2 2 Maps .............................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................................................... 4 1 PART 1: RURAL LAND IN ALPINE SHIRE .......................................................................................................... 6 1.1 State policy context ............................................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1 State Planning Policy Framework (SPPF): ................................................................................ 6 1.2 Regional policy context ......................................................................................................................... 9 1.2.1 Hume Regional Growth Plan.................................................................................................... 9 1.2.2 Upper Ovens Valley Scenario Analysis .................................................................................. -

Ovens Fire Complex - Public Land and Road Closures - Updated 9Th Dec 2019

Ovens Fire Complex - Public Land and Road Closures - Updated 9th Dec 2019 H u g h e s N k L in a ! e n M e Meadow Creek ile T Kangaroo Creek rk rk Ovens River T H C o f Hurdle Creek ! E fm ! S ! d a d R n R ! ! k Buffalo River ! t e R e ! s r C u ! a d r l Mount B ffal ! P r o Rd e e ! ttife d E n t Mt McLeod r s R or F r C k ! rk boo ng d T ar o o ts C L le Spo Rd c t Pratts Lan M n e t u h M s e h C - i ! d Black Range Creek E e Lake Buffalo n a k L B r Mt Em s u T n u L T k a a k r f e ke k f e e Bu Mt Emu a r ffa C D lo l D y - o ck Whi o Ro tf z ield R Rd e Buckland River d iv r T e B his R ! t r r l P o ! e d T R r w o o r d ! ! H f i e rte r u n !! m a rs a T ! d T ! rk W p r !! h k ! T The Horn r T D k r k uc k ! B at ! l i ! a T ! ! ! r ! ! c k ! ! k D Ran e ge k v Tr i ! ls ! ie Sp ! old ur C ! T G r r C k Rose River ! e Morses Creek a e ! k r s ! R o ! d n ! M T e Rd ! d ! R r ! o a ! o k se l All Buffalo River camp sites are open. -

BEL Deforestation Solution

BEL Deforestation Solution I. Abstract Deforestation is the result of forests decreasing due to people illegally cutting down trees and wild fires. It increases CO2 in the atmosphere, which leads to global warming. It is destroying the habitats of many animals and beautiful forests. According to the World Wildlife Organization, 15% of all greenhouse gas emissions are caused by deforestation. Additionally, the World Wildlife Organization says that 1.25 billion people worldwide rely on forests for shelter, livelihood, water, fuel, and food security. Our future technology solution is artificial trees to power the drones and absorb CO2 as well as drones to protect our forest, put out fires, and replant trees. II. Description 1. Present Technology Satellite monitoring is currently used to understand if the forests are changing and what are the causes for those changes. One example of this is Global Forest Watch 2.0. It was developed by “Google, in partnership with the University of Maryland and the UN Environment Programme,” according to enviromentalleader.com. This forest watch uses “satellite technology, data sharing and human networks around the world.”1 The purpose of this is to give real-time information regarding deforestation to all countries across the world. The limitation is it’s a monitoring system, and cannot actually stop deforestation without something to act on it. One current technology that exists for replanting trees is drone planting. Drone planting is drones dropping seed pods. Over time, the pods dissolve and the seeds pop out. The benefits of this technology are that this can easily reach hard-to find areas. -

FIGHTING FIRE with FIRE: Can Fire Positively Impact an Ecosystem?

FIGHTING FIRE WITH FIRE: Can Fire Positively Impact an Ecosystem? Subject Area: Science – Biology, Environmental Science, Fire Ecology Grade Levels: 6th-8th Time: This lesson can be completed in two 45-minute sessions. Essential Questions: • What role does fire play in maintaining healthy ecosystems? • How does fire impact the surrounding community? • Is there a need to prescribe fire? • How have plants and animals adapted to fire? • What factors must fire managers consider prior to planning and conducting controlled burns? Overview: In this lesson, students distinguish between a wildfire and a controlled burn, also known as a prescribed fire. They explore multiple controlled burn scenarios. They explain the positive impacts of fire on ecosystems (e.g., reduce hazardous fuels, dispose of logging debris, prepare sites for seeding/planting, improve wildlife habitat, manage competing vegetation, control insects and disease, improve forage for grazing, enhance appearance, improve access, perpetuate fire- dependent species) and compare and contrast how organisms in different ecosystems have adapted to fire. Themes: Controlled burns can improve the Controlled burns help keep capacity of natural areas to absorb people and property safe while and filter water in places where fire supporting the plants and animals has played a role in shaping that that have adapted to this natural ecosystem. part of their ecosystems. 1 | Lesson Plan – Fighting Fire with Fire Introduction: Wildfires often occur naturally when lightning strikes a forest and starts a fire in a forest or grassland. Humans also often accidentally set them. In contrast, controlled burns, also known as prescribed fires, are set by land managers and conservationists to mimic some of the effects of these natural fires. -

Genetic Diversity of Willows in Southeastern Australia

Genetic diversity of willows in southeastern Australia Tara Hopley Supervisors: Andrew Young, Curt Brubaker and Bill Foley Biodiversity and Sustainable Production CSIRO Plant Industry Pilot study 1. Quantify level of genetic differentiation among catchments 2. Determine the power of molecular fingerprinting to track seed movement across the landscape 3. Assess relative importance of vegetative versus seed reproduction 4. Quantify the spatial scale of seed dispersal 5. Revisit the appropriate landscape scale for effective willow eradication and invasion risk assessment East Gippsland study area Sampling • 50 mature trees in four Buffalo R putative source catchments Morses Ck • 30 mature trees and 38 seedlings in one target Ovens R catchment (Dargo River ) Buckland R Fingerprinting • Individuals genotyped with two marker systems (SSRs and AFLPs) Dargo R Structure analysis (Pritchard et al. 2000) Buffalo R Morses Ck • Bayesian probability Buffalo River M orses Creek 1 2 3 1 4 2 modelling 3 5 4 Ovens R 5 • Model I: no a priori Ovens River 1 2 3 4 information 5 Buckland River – adults fall into five 1 2 3 4 genetic groups 5 – general alignment with populations Buckland R Dargo River Adults Dargo R Structure analysis (Pritchard et al. 2000) Buffalo R Morses Ck • Bayesian probability Buffalo River M orses Creek 1 2 3 1 4 2 modelling 3 5 4 Ovens R 5 • Model I: no a priori Ovens River 1 2 3 4 information 5 Buckland River – adults fall into five 1 2 3 4 genetic groups 5 – general alignment with populations Buckland R – Dargo seedlings mixed assignments Dargo River Seedlings – >70% not local origin seedlings – Ovens R and Morses Ck (>50km) Dargo R Seed or pollen? Buffalo Buckland Morses Ovens Dargo Dargo River River Creek River River River Adults Seedlings • Model II: a priori population assignments • Apparent pollen and seed movement across catchments is evident Conclusions of pilot study • AFLPs work well as genetic markers in Salix cinerea for measuring gene flow. -

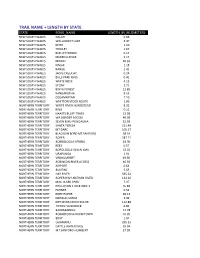

Trail Name + Length by State

TRAIL NAME + LENGTH BY STATE STATE ROAD_NAME LENGTH_IN_KILOMETERS NEW SOUTH WALES GALAH 0.66 NEW SOUTH WALES WALLAGOOT LAKE 3.47 NEW SOUTH WALES KEITH 1.20 NEW SOUTH WALES TROLLEY 1.67 NEW SOUTH WALES RED LETTERBOX 0.17 NEW SOUTH WALES MERRICA RIVER 2.15 NEW SOUTH WALES MIDDLE 40.63 NEW SOUTH WALES NAGHI 1.18 NEW SOUTH WALES RANGE 2.42 NEW SOUTH WALES JACKS CREEK AC 0.24 NEW SOUTH WALES BILLS PARK RING 0.41 NEW SOUTH WALES WHITE ROCK 4.13 NEW SOUTH WALES STONY 2.71 NEW SOUTH WALES BINYA FOREST 12.85 NEW SOUTH WALES KANGARUTHA 8.55 NEW SOUTH WALES OOLAMBEYAN 7.10 NEW SOUTH WALES WHITTON STOCK ROUTE 1.86 NORTHERN TERRITORY WAITE RIVER HOMESTEAD 8.32 NORTHERN TERRITORY KING 0.53 NORTHERN TERRITORY HAASTS BLUFF TRACK 13.98 NORTHERN TERRITORY WA BORDER ACCESS 40.39 NORTHERN TERRITORY SEVEN EMU‐PUNGALINA 52.59 NORTHERN TERRITORY SANTA TERESA 251.49 NORTHERN TERRITORY MT DARE 105.37 NORTHERN TERRITORY BLACKGIN BORE‐MT SANFORD 38.54 NORTHERN TERRITORY ROPER 287.71 NORTHERN TERRITORY BORROLOOLA‐SPRING 63.90 NORTHERN TERRITORY REES 0.57 NORTHERN TERRITORY BOROLOOLA‐SEVEN EMU 32.02 NORTHERN TERRITORY URAPUNGA 1.91 NORTHERN TERRITORY VRDHUMBERT 49.95 NORTHERN TERRITORY ROBINSON RIVER ACCESS 46.92 NORTHERN TERRITORY AIRPORT 0.64 NORTHERN TERRITORY BUNTINE 5.63 NORTHERN TERRITORY HAY RIVER 335.62 NORTHERN TERRITORY ROPER HWY‐NATHAN RIVER 134.20 NORTHERN TERRITORY MAC CLARK PARK 7.97 NORTHERN TERRITORY PHILLIPSON STOCK ROUTE 55.84 NORTHERN TERRITORY FURNER 0.54 NORTHERN TERRITORY PORT ROPER 40.13 NORTHERN TERRITORY NDHALA GORGE 3.49 NORTHERN TERRITORY -

Prescribed Fire 101 Controlling Fire for Ecological Benefits

Prescribed Fire 101 Controlling Fire for Ecological Benefits The very foundation of fire ecology is the premise that wildland fire is neither innately destructive nor in the best interest of every forest. Fire causes change and change has its own value. Certain forest biomes benefit more than others. Change by fire is biologically necessary to maintain many healthy ecosystems in fire-loving plant communities and resource managers have learned to use fire to cause changes in plant and animal communities to meet their objectives. Varying fire timing, frequency, and intensity produces differing resource responses that create the correct changes for habitat manipulation. A History of Fire Indigenous peoples used fire in virgin pine stands to provide better access, improve hunting, and ridding the land of undesirable species so they could farm. Early settlers observed this and many continued the practice of using fire as a beneficial agent. Destructive wildfire was also prevented by burning under safer conditions with the necessary tools for control. An appropriately "controlled" burn would reduce fuels that fed dangerous fires and assure that the next fire season would not bring destructive, property damaging fire. But increased tree planting and an encroaching urban interface called attention the wildfire problem and led foresters to advocate the exclusion of all fire from the woods. This, in part, was due to the wood boom after WWII and the planting of millions of acres of susceptible trees that were vulnerable to fire in the first few years of establishment. This "exclusion of fire" was not always an acceptable option - and this dramatically learned in Yellowstone National Park after decades of excluding fire. -

2.4 Effects of Controlled Burns on the Bulk Density and Thermal Conductivity of Soils at a Southern Colorado Site W. J. Massman1

2.4 Effects of controlled burns on the bulk density MEF is a forested, high elevation, semi-arid, site and thermal conductivity of soils at a dominated by ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) and southern Colorado site by soils that are derived mostly from biotite gran- ite and associated igneous rocks of the Pikes Peak W. J. Massman1,2 and J. M. Frank2 batholith. Two different MEF experimental burn sites were used for this study. The first site, burned in January 2002, is described by Massman et al. (2003) 1. Introduction and Massman and Frank (2004). The second site, de- Throughout the world fire plays an important role scribed by Massman et al. (2006), was burned during in the management and maintenance of ecosystems. April of 2004. Both these sites have moderately dis- However, if a fire is sufficiently intense, soil can be turbed soils, but the first burn site had once been used irreversibly altered and the ability of vegetation, par- as an access road to other parts of the forest, so the ticularly forests, to recover after a fire can be seriously soils there are more compacted (hence denser) than at compromised. Because fire is frequently used by land the second site. The consequences of this additional managers to reduce surface fuels, it is important to complication to the sampling strategy at the first site know if and how soil properties may change as a con- are discussed in more detail below. sequence of the fire-associated soil heat pulse. At the time we sampled the soils more than 3.5 years The present study outlines an experiment to deter- had passed after the first burn and about 1.5 years mine the effect that controlled burns can have on the had elapsed after the second. -

Henrico County Division of Fire Office of the Fire Marshal

Henrico County Division of Fire Office of the Fire Marshal Regulations for Open Burning Tree and Garden Trimmings/Bonfires Open burning shall be allowed after obtaining the approval and permit from the Fire Marshal for the destruction of any vegetation that would be commonly removed from trees, shrubs or garden plants during the normal pruning process. Also, any twigs or small branches that fall from trees during normal thunderstorms or windy days. And any plants removed from a garden after the growing season (corn stalks, tomato vines, bean vines etc.) The Fire Marshal shall prohibit open burning that will be offensive or objectionable due to smoke or odor emissions when atmospheric conditions or local circumstances make such fires hazardous. The Fire Marshal shall order the extinguishment, by the permit holder or the fire department, of any open burning that creates or adds to a hazardous or objectionable situation. 1. Possession of a permit for open burning does not exempt or excuse a person from the consequence, damages or injuries which may result from such conduct, nor does it excuse or exempt any person from complying with all applicable laws, ordinances, regulations, and orders of the federal government, Commonwealth of Virginia and/or Henrico County. 2. Burning of the following is PROHIBITED: a. Toxic or hazardous materials or containers for such materials. b. Rubber tires, asphaltic material, crankcase oil, impregnated wood, or other rubber or petroleum-based materials. c. Paper, used lumber or trade waste. d. Building and/or demolition material. e. Household/commercial trash or refuse. 3. A “written permit” is required for the open burning of tree and/or garden trimmings. -

Appendix E: Sample Burn Plan Refuge Or Station: San Francisco Bay NWR Complex Unit

Appendix E: Sample Burn Plan Refuge or Station: San Francisco Bay NWR Complex Unit : Antioch Dunes NWR 11646 Date: Prepared By: Date: Roger P. Wong Prescribed Fire Burn Boss Reviewed By: Date: ADR Assistant Refuge Manager The approved Prescribed Fire Plan constitutes the authority to burn, pending approval of Section 7 Consultations, Environmental Assessments, or other required documents. No one has the authority to burn without an approved plan or in a manner not in compliance with the approved plan. Prescribed burning conditions established in the plan are firm limits. Actions taken in compliance with the approved Prescribed Fire Plan will be fully supported, but personnel will be held accountable for actions taken which are not in compliance with the approved plan. Approved By: Date: Margaret Kolar Project Leader San Francisco Bay/Don Edwards NWR 85 PRESCRIBED FIRE PLAN Refuge: San Francisco Bay NWR Complex Refuge Burn Number: Sub Station: Antioch Dunes NWR Fire Number: Name of Areas: Stamm Unit Total Acres To Be Burned: 11 acres divided into 2 units to be burned over one day Legal Description: Stamm Unit T.2N; R.2E, Section 18 Lat. 38 01', Long. 121 48' Is a Section 7 Consultation being forwarded to Fish and Wildlife Enhancement for review? Yes No (circle). Biological Opinion dated June 11, 1997 (Page 2 of this PFP should be a refuge base map showing the location of the burn on Fish and Wildlife Service land.) The Prescribed Fire Burn Boss/Specialist must participate in the development of this plan. I. GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF BURN UNIT Physical Features and Vegetation Cover Types Burn Unit 1B -- Stamm Unit - Hardpan (4 acres): Predominantly annual grasses interspersed with YST and bush lupin “skeletons” from previous year’s prescribed burn. -

Study of Old-Growth Forest in Victoria's North East

Study of Old-growth Forest in Victoria’s North East Department of Natural Resources and Environment Victoria Forests Service Technical Reports 98-1 June 1998 Copyright © Department of Natural Resources and Environment 1998 Published by the Department of Natural Resources and Environment PO Box 500, East Melbourne Victoria 3002, Australia http://www.nre.vic.gov.au This publication is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, photocopying or otherwise, without prior permission of the copyright owner. The National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in- Publication entry: Study of Old-growth Forest in Victoria’s North East. Bibliography. ISSN 1443-1106 ISBN 0 7311 4440 6 1.Forest Management - Victoria, Northeastern. 2.Forests and forestry - Victoria, Northeastern. 3.Old-growth forests - Victoria, Northeastern. I. Victoria. Dept. of Natural Resources and Environment. (Series: Forests Service Technical Report ; 98 -1). 634.909945 General Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss, or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. Cover design and layout: Wamen Press Cover photographs: 1. Montane/ Sub-alpine Woodland near Mt Howitt - Geoff Lucas, 2. Alpine Complex - from Tims Spur, - Geoff Lucas Printing by Wamen Press i FOREWORD During the early 1990’s the then Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (CNR) and the Australian Heritage Commission (AHC) reached joint agreement on a series of studies to evaluate National Estate values in Victoria’s North East.