Alexandra Tuite Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sebastian Di Mauro

Sebastian Di Mauro BORN Innisfail, Queensland, Australia ACADEMIC QUALIFICATIONS 2014-2015 Doctor of Philosophy, Griffith University 1993-1996 Master of Arts (Visual Arts), Monash University 1990-1991 Graduate Diploma of Arts, (Visual Arts), Monash University 1987 Bachelor of Arts, Queensland College of Art, Brisbane 1981-1983 Diploma of Teaching, Brisbane College of Advanced Education SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 GREENBACK MARS Gallery, Melbourne, Victoria 2019 GREENBACK, Onespace Gallery, Brisbane, Queensland 2014 Surf ‘n’ Turf, Gold Coast City Art Gallery, Gold Coast 2010 Scuta, Dianne Tanzer Gallery, Melbourne 2009 Footnotes of a verdurous tale, Sebastian Di Mauro 1987-2009, QUT Art Museum, Brisbane Scuta, Sullivan+Strumpf Fine Art, Sydney 2008 Evergreen, Dianne Tanzer Gallery, Melbourne 2007 Lasciare, Victorian Tapestry Workshop Gallery, Melbourne Archimedes’ Bath, Sullivan + Strumpf Fine Art, Sydney Suburban Abstractions 4, Mackay Artspace, Mackay Suburban Abstractions 3, Gladstone Regional Art Gallery, Gladstone 2006 Float, Dianne Tanzer Gallery, Melbourne 2005 Suburban Abstractions 2, Bundaberg Arts Centre, Bundaberg UAM Project Show: Catherine Brown, Denise Green, Sebastian Di Mauro and Tom Risley, University Art Museum, University of Queensland, Brisbane the grass is greener, Newcastle Regional Gallery, Newcastle 2004 Suburban Abstractions: Lifts Project, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra Suburban Abstractions: Roots, Dianne Tanzer Gallery, Melbourne Pivot, Umbrella Studios, Townsville Turf Sweet, Maroondah Art Gallery, Ringwood, -

Local Heritage Register

Explanatory Notes for Development Assessment Local Heritage Register Amendments to the Queensland Heritage Act 1992, Schedule 8 and 8A of the Integrated Planning Act 1997, the Integrated Planning Regulation 1998, and the Queensland Heritage Regulation 2003 became effective on 31 March 2008. All aspects of development on a Local Heritage Place in a Local Heritage Register under the Queensland Heritage Act 1992, are code assessable (unless City Plan 2000 requires impact assessment). Those code assessable applications are assessed against the Code in Schedule 2 of the Queensland Heritage Regulation 2003 and the Heritage Place Code in City Plan 2000. City Plan 2000 makes some aspects of development impact assessable on the site of a Heritage Place and a Heritage Precinct. Heritage Places and Heritage Precincts are identified in the Heritage Register of the Heritage Register Planning Scheme Policy in City Plan 2000. Those impact assessable applications are assessed under the relevant provisions of the City Plan 2000. All aspects of development on land adjoining a Heritage Place or Heritage Precinct are assessable solely under City Plan 2000. ********** For building work on a Local Heritage Place assessable against the Building Act 1975, the Local Government is a concurrence agency. ********** Amendments to the Local Heritage Register are located at the back of the Register. G:\C_P\Heritage\Legal Issues\Amendments to Heritage legislation\20080512 Draft Explanatory Document.doc LOCAL HERITAGE REGISTER (for Section 113 of the Queensland Heritage -

Project Brochure

Founded with a passion for architecture and a proud pioneering spirit, Kokoda Property creates living landmarks of craftsmanship, superior quality and thoughtful design. In 23 years our award-winning luxury residences have made the Kokoda Property name synonymous with quality and style, cementing our reputation as one of Australia’s most respected developers. THE VISION - THOUGHTFUL, AWARD-WINNING DESIGN - We seek out the nation’s premier locations and create bespoke residences to match, both in design and style. Offering unrivalled lifestyle and luxury, our homes live ADDRESSES up to our promise, receiving multiple industry awards for design excellence. SUPERIOR QUALITY & CRAFTSMANSHIP OF - Our standards are as high as yours. Every touch point of a Kokoda Property residence is carefully considered and cleverly designed. With meticulous attention to detail and luxury inclusions as standard, we aim DISTINCTION to exceed your expectations every time. BESPOKE, PERSONAL SERVICE - We understand that buying a new home is one of life’s most significant investments. Kokoda Property is with Defined by award-winning design, superior quality you every step of the way to make the journey simple and seamless, and help you personalise your and proud heritage, Kokoda Property creates luxury residence to suit your individual style. residences in Australia’s most desired locations. PROUD HERITAGE IN LUXURY - We began 23 years ago, building luxury homes in Melbourne’s most elite suburbs. Today our philosophy remains unchanged and our finished product serves as our proud legacy. Every Kokoda Property residence represents an unfaltering commitment to quality. HOMES YOU’LL LOVE LIVING IN - Our ultimate satisfaction comes from creating homes you’ll adore, inside and out. -

Chemist Warehouse Participating Agents

Agency Name Street Address MALL NEWS BEENLEIGH 19-21 MAIN STREET BEENLEIGH QLD 4207 KIRRA BEACH NEWS 48 MUSGRAVE STREET COOLANGATTA QLD 4225 PADDINGTON NEWS 199 LATROBE TERRACE PADDINGTON QLD 4064 JUNCTION NEWS 500 IPSWICH ROAD ANNERLEY QLD 4103 WEST SIDE STORY NEWS 85 BOUNDARY STREET WEST END QLD 4101 KENMORE NEWS 2061-2069 MOGGILL ROAD KENMORE QLD 4069 GUMDALE NEWSXPRESS 696 NEW CLEVELAND ROAD GUMDALE QLD 4154 AUSTRALIA CLEVELAND NEXTRA NEWS CLEVELAND SHOPPING CENTRE 91 MIDDLE STREET CLEVELAND QLD 4163 WEST END NEWS 199 BOUNDARY STREET WEST END QLD 4101 SPRINGWOOD MALL NEWS CENTRO SPRINGWOOD SHOPPING CENTRE 9 FITZGERALD AVE SPRINGWOOD QLD 4127 WOOLLOONGABBA NEWS 7 LOGAN RD WOOLOONGABBA QLD 4102 ALEXANDRA HILLS NEWS 71 CAMBRIDGE DRIVE ALEXANDRA HILLS QLD 4161 THE GAP NEWSXPRESS 1000 WATERWORKS ROAD THE GAP QLD 4061 INDOOROOPILLY S/C METRO N INDOOROOPILLY SHOPPINGTOWN 322 MOGGILL ROAD INDOOROOPILLY QLD 4068 CAMP HILL NEWS 569 OLD CLEVELAND ROAD CAMP HILL QLD 4152 REGENTS PARK NEWS 3358-3374 MOUNT LINDESAY HIGHWAY REGENTS PARK QLD 4118 CRIBB STREET NEWS 23 LITTLE CRIBB STREET MILTON QLD 4064 ST LUCIA NEWS 219 HAWKEN DRIVE ST LUCIA QLD 4067 OXFORD STREET NEWS 134 OXFORD STREET BULIMBA QLD 4171 HOLLAND PARK NEWS 105 SEVILLE ROAD HOLLAND PARK QLD 4121 BOOVAL NEWS 38 SOUTH STATION ROAD BOOVAL QLD 4304 GREENSLOPES NEWS 700 LOGAN ROAD GREENSLOPES QLD 4120 413 WEST Wacol - QLD SOUTH BRISBANE NEWS 133 GREY STREET SOUTH BRISBANE QLD 4101 SPRINGWOOD THE LUCKY CHAR ARNDALE SHOPPING CENTRE 17-27 CINDERELLA DRIVE SPRINGWOOD QLD 4127 GIVEN TERRACE NEWSAGENCY -

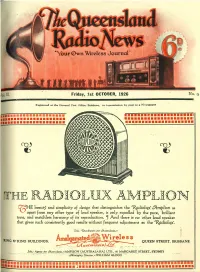

QRN Oct 1926 .Pdf

-- vol. II. Friday, 1st OCTOBER, 1926 No. 9 Registered at the General Post O ffice, Brisbane, or tr ans mission by post as a Nt w spai:-e r 7••••••••••••n••••••· •••••••m•••••••••••••I •••••••••••••••••••• ···················••1••••••••••••••••••••• THE RADIOLUX AMPLION C(9'HE beauty and simplicity of design that distinguishes the ~gdiolu.)( c?t.mplion as apart from any other type of loud speaker, is only equalled by the pure, brilliant tone, and matchless harmony of its reproduction. ' And there is no otber loud speaker that gives such consistently good results without frequent adjustment as the 'RpdioluJ(. TS oie_.,-· 'Dist1ibut~rs · for -.::5\ ~stralasia ....... ill ~ : " KING &- KING Bt:JILDINGS, QUEEN STREET, BRISBANE ' <·- ,_ . ';_"- ______ ...... ___ ·-: Sole.; Agents Jor .9.ustralasia_,.,AMPLION [AUSTRALASIA] LTD., 56 MARGARET STREET, SYDNEY . -~'.:'."--- ··---. --------- "'&i[;i;.-;;ging D ir~~ ,,;~::,.WfLLI AKi' 'EiL6dcr ·-:::. ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• ·· · ····················~··················•• 1 ••············· WHAT SPLITDORF has made possible lor you ! Musical tones-clear, pure, mellow! We a re t he Sole Q ueensland Speech-sharp, dis tinct, understand Distributors for this set and able ! st rongly recommend dealers to get in touch with us now ::i. bout Volume-when volume is desired. !.,_ Distance if that is your pleasure. L . Assuredly the best low-priced S And, beyond all the qualities of the Valve Set ever offered to the reception, is the absolute assurance public. of unfaltering, dependable, perform- ance-always. - '~hi s Five V alve, inherent ly neutra _,.Z7/J.O/· lised, _tuned radio frequency receiver Accessories Extra combmes ease of operation and handsome appearance ''with' the g reat est economy in first cost and maintenance. E ncased in an attra: tive cabinet, with large t unin g- dials and_ richly 'finished metal panel it is an m strument to be proud of. -

Cover for Visual Reference Only

Cover for visual reference only Cover for visual reference only An inspired landmark at the cusp of Newstead and Teneriffe, Le Bain evokes the hedonistic pleasures of Les Bains Paris, a luxurious destination known for its glamourous night life and 5-star boutique hotel. Le Bain is another triumph by Cavcorp, a showcase of fine craftsmanship, architectural precision and innovation. Delivering the best of luxury living, Le Bain will pamper privileged residents with unparalleled service and exclusive amenity. Its dedicated concierge and excellent property management will ensure your needs are cared for, and the building is nothing short of perfection. A collection of only eight exquisite penthouses crown this spectacular masterpiece, awaiting the most discerning owners. Embrace an indulgent lifestyle most can only dream of, in a destination made for a beautiful life. Damien Cavallucci Cavcorp LE BAIN NEWSTEAD THE CAVCORP STORY 1960 Cavallucci family migrates to Australia from Italy. 1996 Damien Cavallucci acquires his Bachelor’s degree of Engineering from the University of Queensland. 1999 After selling his car, Damien purchases his first building and is able to substantially increase the value and sell for a small profit. 2003 Cavcorp founded and commences residential, commercial and industrial projects. 2004 Damien partners with his brother Michael Cavallucci and his sister Lisa Cavallucci to create a strong dynamic team. 2 2005 Cavcorp develops Cargo Business Park, recognised as one of the best business parks in Queensland with global tenants including Nike, Telstra, Huawei, Asics and Betta Electrical with an end value of $240 billion. 2007 Cavcorp completes multi-award-winning 100-unit residential development, winning Masters Builders Award ‘Developments up to $30 million’ for the state of Queensland. -

Chemist Warehouse Autumn 2021 Allocations

Name Address KENMORE NEWS 2061-2069 MOGGILL ROAD KENMORE QLD 4069 THE LUCKY CHARM VIC POINT VICTORIA POINT LAKESIDE SHOPPING CENTRE 21-27 BUNKER ROAD VICTORIA POINT QLD 4165 BOOVAL NEWS 38 SOUTH STATION ROAD BOOVAL QLD 4304 THE GAP NEWSXPRESS 1000 WATERWORKS ROAD THE GAP QLD 4061 CORNER HOUSE NEWS 195 PRESTON ROAD MANLY WEST QLD 4179 IPSWICH CITY NEWS 193 BRISBANE STREET IPSWICH QLD 4305 KIRRA BEACH NEWS 48 MUSGRAVE STREET COOLANGATTA QLD 4225 WESTPOINT NEWS & CASKET WESTPOINT SHOPPING CENTRE 8-24 BROWNS PLAINS RD BROWNS PLAINS QLD 4118 AUSTRALIA EAGLE JUNCTION NEWS 272 JUNCTION ROAD CLAYFIELD QLD 4011 PROTON NEWS 39 MINJUNGBAL DRIVE TWEED HEADS SOUTH NSW 2486 OXFORD STREET NEWS 134 OXFORD STREET BULIMBA QLD 4171 REDLAND BAY NEWS 11 STRADBROKE STREET REDLAND BAY QLD 4165 GUMDALE NEWSXPRESS 696 NEW CLEVELAND ROAD GUMDALE QLD 4154 AUSTRALIA FULL THROTTLE BORONIA PK 7 VALERIE CL EDENS LANDING QLD 4207 AUSTRALIA NORMAN PARK CENTRAL NEWS 183 BENNETTS ROAD NORMAN PARK QLD 4170 CORNER STORE NEWS 8 STATION ROAD INDOOROOPILLY QLD 4068 BURSTALL AVENUE NEWS 185 BELMONT ROAD BELMONT QLD 4153 KINGSCLIFF NEWSAGENCY 96 MARINE PARADE KINGSCLIFF NSW 2487 BURANDA NEWS 140 LOGAN ROAD WOOLLOONGABBA QLD 4102 MOUNTAIN VIEW NEWS 965-967 LOGAN ROAD HOLLAND PARK WEST QLD 4121 GAILEY NEWS SHOP 7 144 INDOOROOPILLY RD TARINGA QLD 4068 AUSTRALIA PADDINGTON NEWS 199 LATROBE TERRACE PADDINGTON QLD 4064 LOGANLEA FULL THROTTLE 7 VALERIE CL EDENS LANDING QLD 4207 AUSTRALIA WOOLLOONGABBA NEWS 7 LOGAN RD WOOLOONGABBA QLD 4102 ST LUCIA NEWS 219 HAWKEN DRIVE ST LUCIA QLD -

Legislative Assembly Hansard 1981

Queensland Parliamentary Debates [Hansard] Legislative Assembly TUESDAY, 24 MARCH 1981 Electronic reproduction of original hardcopy 404 Ministerial Statements [24 MARCH 1981] Ministerial Statements TUESDAY, 24 IMARCH 1981 The committee has now completed^ its deliberations, and its findings and recom mendations are embodied in a 425-page report. I am sure members wiU be sitbfied .that the committee has effectively carded out Mr SPEAKER (Hon. S. J. MuUer, Fassi the commission which it was given^ fern) read prayers and took the chair at A summary of the committee's main recom 11 a.m. mendation b as foUows:— The ambulance service should retain its organisational independence and not PAPERS become incorporated into either the Public The following papers were laid on the Service system or the State hospital system. table:— It should be controlled and governed by a central body caUed the "Queensland Orders in Council under— Ambulance Service Board" and administra Supreme Court Act 1921-1979. tive responsibUity should be devolved into State Housing Act 1945-1979. two further tiers in the form of three Electiicity Act 1976-1980. divisions and 90 ambulance centres through Mines Regulation Act 1964-1979. out the State. Harbours Act 1955-1980. Ambulance superintendents should be in charge of administration and operations Section 43 of the Metropolitan Transit throughout the State, subject to a central Authority Act 1976-1979. exeoitive and the Queensland Ambulance Service Board Area ambulance committees should be retained in an advbory capacity MINISTERIAL STATEMENTS to exercise certain prescribed functions and to lend assistance in fund-rabing. AMBULANCE SERVICES IN QUEENSLAND Standardised specifications for motor Hon. -

QRE-Merged 180..191

Book Reviews Bronwen Levy’s introduction to this volume suggests that it did matter that Helen was a woman artist, rather than an ungendered ‘pen’. She was part of a creative scene in South-East Queensland in the 1960s and 1970s that included poets Bruce Dawe, Rodney Hall, Oodgeroo Noonuccal and Tom Shapcott. This volume, published with the support of the Jani Haenke Charitable Trust, redeems her forgotten creative life. Perhaps it might also be a catalyst for research that explores the ‘creative community’ that is contemporary Ipswich and that places her work in a wider Queensland literary history. Kay Ferres Griffith University k.ferres@griffith.edu.au doi 10.1017/qre.2019.16 Melissa Fagan, What Will Be Worn: A McWhirters Story, Brisbane: Transit Lounge, 2018, 296 pp., ISBN 9 7819 2576 0095, A$29.99. When Melissa Fagan stands before the famed McWhirters building in Valley Corner, she tries ‘to decipher what this immutable object, this icon, means to the city and me’, but finds that ‘the building is in my way’ (2018: 8). In this book, she tries to move beyond the Art Deco department store to examine the lives and work of the women who were connected to it by blood and marriage. Weaving together research, reportage, imagined lives and personal memoir, she illuminates the impact of wealth, social expectations and loss across five generations of women. It is more her mother’s story than her own, Fagan explains in her prologue, but to know the life of her mother means knowing the women who formed her. -

Brisbane City Plan, Appendix 2

Introduction ............................................................3 Planting Species Planning Scheme Policy .............167 Acid Sulfate Soil Planning Scheme Policy ................5 Small Lot Housing Consultation Planning Scheme Policy ................................................... 168a Air Quality Planning Scheme Policy ........................9 Telecommunication Towers Planning Scheme Airports Planning Scheme Policy ...........................23 Policy ..................................................................169 Assessment of Brothels Planning Scheme Transport, Access, Parking and Servicing Policy .................................................................. 24a Planning Scheme Policy ......................................173 Brisbane River Corridor Planning Scheme Transport and Traffic Facilities Planning Policy .................................................................. 24c Scheme Policy .....................................................225 Centre Concept Plans Planning Scheme Policy ......25 Zillmere Centre Master Plan Planning Scheme Policy .....................................................241 Commercial Character Building Register Planning Scheme Policy ........................................29 Commercial Impact Assessment Planning Scheme Policy .......................................................51 Community Impact Assessment Planning Scheme Policy .......................................................55 Compensatory Earthworks Planning Scheme Policy ................................................................. -

Newstead & Teneriffe

your ULTIMATE location and living EXPERIENCE 2 3 Panoramic view of Brisbane. Brisbane is a global city where art, business, LIVING WELL BEING education and environment live in perfect balance. REVELRY gastronomy CITYLUXURY LIFE technology GREEN CONNECTIVITY public realm SPACE GALLERYindividual designed CULTURE 2 3 Inspiration through LAVISH DESIGN Our vision for Lucent has always been one of transformation – regenerating an existing location to fulfill its true potential. To do this, CAVCORP has teamed up with renowned Award winning architect Shane Plazibat to create an entirely new destination for Brisbane. By working together from the outset, as a collective, we have been able to create something truly special and make the vision a reality. Arranged over fifteen floors, Lucent sets a benchmark for modern architecture in Brisbane. In part, all elevations will have shimmering champagne sliding screens, rippling across the façade, the screens create an ever-changing skin to the building. The façade is articulated further by four separate vertical green landscaping zones that span 45 meters in height. A curtain glass wall accentuates the building elevation and creates a dramatic effect to the stunning corner apartments. With 190 units in total, greater emphasis has been given to create amazing living spaces designed from the ‘inside-out’ to ensure privacy while maximising daylight and fresh air. The width of both the winter gardens and balconies has been maximised to facilitate outdoor living that natural blends into the two acres of landscaped and beautifully verdant gardens. Lucent’s signature shimmering champagne sliding screens transform the balconies into outdoor living rooms Looking down onto a central Main Plaza with pedestrian walkways, luscious greenery and vibrant restaurants, Lucent will provide a new city destination for Brisbane. -

Thanks to Macca's® You Can Score Yourself a Free Big

Thanks to Macca’s® you can score yourself a free Big Mac®, to celebrate the Brisbane Lions v Gold Coast Suns match, Saturday May 15th on the Gold Coast. It’s simple: if the Lions win, lose or draw, thanks to Macca’s® you win! It’s Mac for a Match! McDonald’s are proud to support all AFL teams in Queensland and this weekend we want to reward all loyal Lions members and fans. So, keep your 2021 Lions mobile membership ticket or match day e-ticket handy and pick up a free Big Mac to celebrate the Lions playing the Suns, the following day on Sunday 16th May 2021 after 10.30 am – lunch sorted! Redeeming your free Big Mac is easy! Brisbane Lions members or match day ticket holders will simply need to show their 2021 mobile membership ticket or membership email confirmation or match day e-ticket at any participating McDonald’s Gold Coast and Brisbane restaurant on Sunday 16th May 2021 to redeem. Regardless of the final outcome. See Terms and Conditions below. TERMS AND CONDITIONS Offer entitles Brisbane Lions Football Club ticket holder/member to one free Big Mac® on Sunday 16th May 2021. Parent/carer must be present for anyone under 14 years to redeem this offer. Available after 10.30am. Show your game e-ticket, mobile membership ticket or membership email confirmation when ordering to receive offer. Limit of one offer per person. Not to be used in conjunction with or to discount any other offer or with an Extra Value Meal®.