Upper Deschutes River Subbasin Fish Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oregon Historic Trails Report Book (1998)

i ,' o () (\ ô OnBcox HrsroRrc Tnans Rpponr ô o o o. o o o o (--) -,J arJ-- ö o {" , ã. |¡ t I o t o I I r- L L L L L (- Presented by the Oregon Trails Coordinating Council L , May,I998 U (- Compiled by Karen Bassett, Jim Renner, and Joyce White. Copyright @ 1998 Oregon Trails Coordinating Council Salem, Oregon All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Oregon Historic Trails Report Table of Contents Executive summary 1 Project history 3 Introduction to Oregon's Historic Trails 7 Oregon's National Historic Trails 11 Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail I3 Oregon National Historic Trail. 27 Applegate National Historic Trail .41 Nez Perce National Historic Trail .63 Oregon's Historic Trails 75 Klamath Trail, 19th Century 17 Jedediah Smith Route, 1828 81 Nathaniel Wyeth Route, t83211834 99 Benjamin Bonneville Route, 1 833/1 834 .. 115 Ewing Young Route, 1834/1837 .. t29 V/hitman Mission Route, 184l-1847 . .. t4t Upper Columbia River Route, 1841-1851 .. 167 John Fremont Route, 1843 .. 183 Meek Cutoff, 1845 .. 199 Cutoff to the Barlow Road, 1848-1884 217 Free Emigrant Road, 1853 225 Santiam Wagon Road, 1865-1939 233 General recommendations . 241 Product development guidelines 243 Acknowledgements 241 Lewis & Clark OREGON National Historic Trail, 1804-1806 I I t . .....¡.. ,r la RivaÌ ï L (t ¡ ...--."f Pðiräldton r,i " 'f Route description I (_-- tt |". -

Our Staff Compiled a List of Their Favorite Top 3 Local Spots for Each Category. We Hope That You Enjoy Them As Much As We Do!

Pronghorn Staff Top 3 Favorites Our staff compiled a list of their favorite top 3 local spots for each category. We hope that you enjoy them as much as we do! Breakfast Bike Trails 1. The Victorian Cafe 1. Phil’s Trail Complex 2. The Sparrow Bakery 2. Wanoga Trail Complex 3. McKay Cottage 3. Swampy Lakes Area Coffee: Hiking Trails 1. Looney Bean 1. Tumalo Falls 2. Backporch Coffee 2. Broken Top, No Name Lake 3. Thump Coffee 3. Elk Lake Elevated Dining: Non-sport Activities 1. The Blacksmith 1. Summer Concerts 2. Bos Taurus 2. Old Mill & Downtown Bend 3. Arianna 3. Cascade Lakes Highway Drive Casual Dining Outdoor Activities 1. Wild Rose 1. Deschutes River float 2. Spork 2. Mt. Bachelor 3. Brother Jon’s Alehouse 3. Fly fishing Local Breweries Must See 1. 10 Barrel Brewing Co. 1. Smith Rock State Park 2. Deschutes Brewery 2. 360 city view from Pilot Butte 3. Crux Fermentation Project 3. Tumalo Falls Contact our Concierge team for more information. 541.693.5311 | [email protected] “Why We Recommend” & More | Breakfast | Chow | Locally-sourced American cuisine served at an artful & comfortable eatery with a full bar & patio. Rotating menu based on region and sourcing. The Sparrow Bakery | Lively, family-friendly bakery for breakfast & lunch, in industrial-chic digs with a patio. Northwest Crossing location has a larger lunch menu. Eastside location is set in a historic building with a large patio. Famous for their ocean roll. Lemon Tree | Downtown, river-facing. Creative breakfast & lunch fare with craft cocktails, coffee & kombucha on tap plus, a gift shop. -

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Towns and Cities

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Towns and Cities Alaska Aialik Bay Alaska Highway Alcan Highway Anchorage Arctic Auk Lake Cape Prince of Wales Castle Rock Chilkoot Pass Columbia Glacier Cook Inlet Copper River Cordova Curry Dawson Denali Denali National Park Eagle Fairbanks Five Finger Rapids Gastineau Channel Glacier Bay Glenn Highway Haines Harding Gateway Homer Hoonah Hurricane Gulch Inland Passage Inside Passage Isabel Pass Juneau Katmai National Monument Kenai Kenai Lake Kenai Peninsula Kenai River Kechikan Ketchikan Creek Kodiak Kodiak Island Kotzebue Lake Atlin Lake Bennett Latouche Lynn Canal Matanuska Valley McKinley Park Mendenhall Glacier Miles Canyon Montgomery Mount Blackburn Mount Dewey Mount McKinley Mount McKinley Park Mount O’Neal Mount Sanford Muir Glacier Nome North Slope Noyes Island Nushagak Opelika Palmer Petersburg Pribilof Island Resurrection Bay Richardson Highway Rocy Point St. Michael Sawtooth Mountain Sentinal Island Seward Sitka Sitka National Park Skagway Southeastern Alaska Stikine Rier Sulzer Summit Swift Current Taku Glacier Taku Inlet Taku Lodge Tanana Tanana River Tok Tunnel Mountain Valdez White Pass Whitehorse Wrangell Wrangell Narrow Yukon Yukon River General Views—no specific location Alabama Albany Albertville Alexander City Andalusia Anniston Ashford Athens Attalla Auburn Batesville Bessemer Birmingham Blue Lake Blue Springs Boaz Bobler’s Creek Boyles Brewton Bridgeport Camden Camp Hill Camp Rucker Carbon Hill Castleberry Centerville Centre Chapman Chattahoochee Valley Cheaha State Park Choctaw County -

Notes from the Desk of the Drc's Executive Director

Summer 2011 VOLUME 5 NUMBER 2 NEWSLETTER OF THE DESCHUTES RIVER CONSERVANCY The mission of the DRC: To restore streamflow and improve water quality in the Deschutes Basin. MARISA CHAPPELL HOSSICK The DRC is beginning to successfully navigate the serpentine nature of water to restore flows to the lower Crooked River while helping North Unit irrigators maintain a viable agricultural economy on the plateaus above. NOTES FROM THE DESK OF THE DRC’S EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, TOD HEISLER Making a Difference by Working Together sults on Whychus Creek, Lake Creek and districts. The net result will be 50 cfs Here at the Deschutes River Conservancy the Crooked River. In four short years of restored streamflows in the Crooked (DRC) we are living proof that when The Deschutes Collaborative imple- River, $300,000 pumping cost savings people of differing views are brought to mented nearly $20 million dollars of for NUID, improved irrigation infra- a table where the expectation is coopera- integrated projects where they are needed structure, and a more reliable supply tion and forging consensus, significant most for salmonid reintroduction. The of water for commercial farmers. This results achieved include 15 cubic feet per long-lasting results can be achieved in model project would not be possible second (cfs) of streamflow restored, six relatively short timeframes. We know without the cooperation of many part- fish passage barriers eliminated, three this because we are coming off another ners including state and federal agen- fantastic year of results on Whychus miles of stream protected from develop- cies, several irrigation districts, Portland Creek and have laid the groundwork for ment, and five miles of habitat restored. -

Comprehensive Plan

Deschutes County Transportation System Plan 2010 - 2030 Adopted by Ordinance 2012-005 August 6, 2012 By The Deschutes County Board of Commissioners EXHIBIT C ORDINANCE 2012-005 Page 1 of 268 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ...................................................................................................... 10 Chapter One Introduction ...................................................................................................................................30 1.1 Geographic Setting .......................................................................................................30 1.2 Transportation Planning ..............................................................................................31 Goal 12 .....................................................................................................................31 Transportation Planning Rule (TPR) ..................................................................31 TPR Requirements for Deschutes County ......................................................33 1.3 Major Changes Since the Adoption of the 1998 Plan ...........................................35 Regional Growth and Destination Resorts ......................................................35 Urban Growth and County Coordination .......................................................36 Public Transportation ...........................................................................................36 Financial Impacts ....................................................................................................37 -

Upper Deschutes River Fish Managementplan

Upper Deschutes River Fish ManagementPlan Draft May22, 1996 Oregon Department of Fish and Wtldlife Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife Page 1 of 431 Upper Deschutes River Basin Fish Management Plan 1996 COMPLETED DISTRICT DRAFT 04/11/96 6:12:58 PM DESCHUTES RIVER from Wickiup Dam to Bend (North Canal Dam) including the tributaries Fall River and Spring River Overview This portion of the basin plan includes the Deschutes River from Wickiup Dam (RM 227) downstream to Bend (North Canal Dam, RM 164.8), Fall River, and Spring River. The Little Deschutes River, a major tributary which enters at RM 193, is not included because of its' length and connection with other waters in the basin. The Little Deschutes River will be presented in a separate section of the basin plan. In the Habitat and Fish Management sections of the following discussion, the Deschutes River will be divided into two sections; Wickiup Dam to Benham Falls (RM 181), and Benham Falls to Bend (North Canal Dam). The reason for this is based on stream morphology and changes in fish populations. Benham Falls is a high gradient natural cascade which separates the Deschutes River into two logical sections with low gradient above the falls and high gradient below. Similarly, fish population composition changes at Benham Falls with brown trout dominant above and rainbow trout dominant below. The remaining sections; location and ownership, fish stocking history, angling regulations, management issues, summary of alternatives and alternatives will be presented as (1) Deschutes River, and (2) Tributaries. In 1987, the Oregon legislature designated the section of Deschutes River from Wickiup Dam to General Patch Bridge, and from Harper Bridge to the north boundary of the Deschutes National Forest as a State Scenic Waterway. -

Benham Falls, OR

Benham Falls, OR Vicinity Location: The trailhead is about 125 miles southeast of Portland, Oregon in the Deschutes National Forest. Directions: From Portland, drive to Bend, about 175 miles. From Bend, drive south onto Cascade Lakes National Scenic Byway passing through several traffic circles. After the last traffic circle, continue on Cascade Lakes Highway / SW Century Dr for about 5 miles. Turn left onto Dillon Falls Rd / NF-41 and continue for 4 miles. After 4 miles, turn left onto a gravel road following signs for Benham Falls. Drive for 2.2 miles on FR 400 and park at the end of the road. There is a restroom at the trailhead. From May 1 through September 30 $5 daily permit or a Northwest Forest pass is required. No on- site purchase for permits. No permits are needed to park between October 1st and June 30. Dogs are allowed and have to be on-leash from May 15th to September 15th. Trail: Deschutes River Trail. There is no geocache on this trail, but there is farther up the Deschutes River Trail. Trail Maps: Topo Map, Download Garmin .gpx file Length and Elevation: 0.4 miles roundtrip. Elevation at the trailhead is 4,150 feet. Elevation gain totals 100 feet. Total gain and loss is 200 feet. Highest elevation is 4,150 feet. Review: April 17, 2014. The short trail goes down several gentle switchbacks through the pine-scented forest with the ever- present roar of the waterfall. The trail is enclosed by a split-rail fence to keep people from trampling the area around the overlook. -

Ralph I. Gifford Photographs, Circa 1910S - 1947

Guide to the Ralph I. Gifford Photographs, circa 1910s - 1947 Title Ralph I. Gifford Photographs (P 218-SG 2) Dates circa 1910s - 1947 (inclusive) 1935-1947 (bulk) Creator Gifford, Ralph I. Summary The Ralph I. Gifford Photographs consist of images taken by Gifford throughout Oregon, primarily during the 1930s and 1940s. The photographs depict many Oregon landmarks and scenes, including the Oregon Coast, Crater Lake, Mount Hood, the Wallowa Mountains, and the Snake River Canyon. The collection includes numerous images of sport fishing as well as several photographs of Native Americans. Ralph Gifford was the son of Benjamin A. Gifford and took over his father©s Portland photography business around 1920. In 1936, Ralph became the first photographer of the newly established Travel and Information Department of the Oregon State Highway Department, a position he held until his death in 1947. Quantity 2.5 cubic feet, including 2089 photographs (17 boxes, including 2 oversize boxes, and 1 map folder) Restrictions on Access Collection is open for research. Oregon State University Libraries, University Archives 121 The Valley Library Oregon State University Corvallis, OR 97331-4501 Phone: 541-737-2165 Email: [email protected] Web: http://osulibrary.oregonstate.edu/archives Finding aid prepared by Lawrence A. Landis; updated by Elizabeth Nielsen, 2011. Funding for encoding this finding aid was provided through a grant awarded by the National Endowment for the Humanities. PDF Created May 28, 2013 Guide to the Ralph I. Gifford Photographs, circa 1910s - 1947 Page 2 of 31 Biographical Note Born in Portland, Ralph I. Gifford (1894-1947) worked in his father©s (Benjamin A. -

Field Guides

Downloaded from fieldguides.gsapubs.org on August 1, 2011 Field Guides Fire and water: Volcanology, geomorphology, and hydrogeology of the Cascade Range, central Oregon Katharine V. Cashman, Natalia I. Deligne, Marshall W. Gannett, Gordon E. Grant and Anne Jefferson Field Guides 2009;15;539-582 doi: 10.1130/2009.fld015(26) Email alerting services click www.gsapubs.org/cgi/alerts to receive free e-mail alerts when new articles cite this article Subscribe click www.gsapubs.org/subscriptions/ to subscribe to Field Guides Permission request click http://www.geosociety.org/pubs/copyrt.htm#gsa to contact GSA Copyright not claimed on content prepared wholly by U.S. government employees within scope of their employment. Individual scientists are hereby granted permission, without fees or further requests to GSA, to use a single figure, a single table, and/or a brief paragraph of text in subsequent works and to make unlimited copies of items in GSA's journals for noncommercial use in classrooms to further education and science. This file may not be posted to any Web site, but authors may post the abstracts only of their articles on their own or their organization's Web site providing the posting includes a reference to the article's full citation. GSA provides this and other forums for the presentation of diverse opinions and positions by scientists worldwide, regardless of their race, citizenship, gender, religion, or political viewpoint. Opinions presented in this publication do not reflect official positions of the Society. Notes © 2009 Geological Society of America Downloaded from fieldguides.gsapubs.org on August 1, 2011 The Geological Society of America Field Guide 15 2009 Fire and water: Volcanology, geomorphology, and hydrogeology of the Cascade Range, central Oregon Katharine V. -

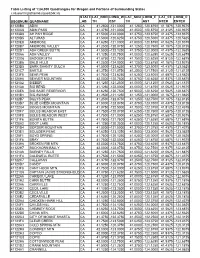

Table Listing of 1:24,000 Quadrangles for Oregon and Portions of Surrounding States C:Research\Gisthemes\Quad24k.Xls USGSNUM

Table Listing of 1:24,000 Quadrangles for Oregon and Portions of Surrounding States c:research\gisthemes\quad24k.xls STATE LAT_NOR LONG_W LAT_SOU LONG_E LAT_CE LONG_C USGSNUM QUADNAME _AB TH EST TH AST NTER ENTER 41120B8 ADIN CA 41.2500 -121.0000 41.1250 -120.8750 41.1875 -120.9375 41120C8 ADIN PASS CA 41.3750 -121.0000 41.2500 -120.8750 41.3125 -120.9375 41123D8 AH PAH RIDGE CA 41.5000 -124.0000 41.3750 -123.8750 41.4375 -123.9375 41120D5 ALTURAS CA 41.5000 -120.6250 41.3750 -120.5000 41.4375 -120.5625 41120E8 AMBROSE CA 41.6250 -121.0000 41.5000 -120.8750 41.5625 -120.9375 41120B7 AMBROSE VALLEY CA 41.2500 -120.8750 41.1250 -120.7500 41.1875 -120.8125 41122D1 ASH CREEK BUTTE CA 41.5000 -122.1250 41.3750 -122.0000 41.4375 -122.0625 41120A6 ASH VALLEY CA 41.1250 -120.7500 41.0000 -120.6250 41.0625 -120.6875 41122G6 BADGER MTN CA 41.8750 -122.7500 41.7500 -122.6250 41.8125 -122.6875 41123B8 BALD HILLS CA 41.2500 -124.0000 41.1250 -123.8750 41.1875 -123.9375 41123D5 BARK SHANTY GULCH CA 41.5000 -123.6250 41.3750 -123.5000 41.4375 -123.5625 41121C7 BARTLE CA 41.3750 -121.8750 41.2500 -121.7500 41.3125 -121.8125 41123F5 BEAR PEAK CA 41.7500 -123.6250 41.6250 -123.5000 41.6875 -123.5625 41120H6 BEAVER MOUNTAIN CA 42.0000 -120.7500 41.8750 -120.6250 41.9375 -120.6875 41121A2 BIEBER CA 41.1250 -121.2500 41.0000 -121.1250 41.0625 -121.1875 41121A8 BIG BEND CA 41.1250 -122.0000 41.0000 -121.8750 41.0625 -121.9375 41120E6 BIG SAGE RESERVOIR CA 41.6250 -120.7500 41.5000 -120.6250 41.5625 -120.6875 41121B1 BIG SWAMP CA 41.2500 -121.1250 41.1250 -121.0000 -

Sunriver to Lava Lands Paved Path Project Environmental Assessment

Sunriver to Lava Lands Paved Path Project Environmental Assessment United States Bend-Fort Rock Ranger District Department of Deschutes National Forest Agriculture Deschutes County, Oregon Forest Service March 2013 Township 19 South, Range 11 East, Sections 16, 17, 20-26 Willamette Meridian For More Information Contact: Scott McBride 63095 Deschutes Market Road Bend, OR 97701 Phone: 541-383-4712 Sunriver to Lava Lands Paved Path EA The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250- 9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Sunriver to Lava Lands Paved Path EA COMMONLY USED ACRONYMS ABA Architectural Barriers Act AASHTO American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials BA Biological Assessment BBC Birds of Conservation Concern BE Biological Evaluation BMP Best Management Practices BO Biological Opinion CEQ Council of Environmental Quality CFR Code -

Oigon Historic Tpms REPORT I

‘:. OIGoN HIsToRIc TPms REPORT I ii Presented by the Oregon Trails Coordinating Council May, 1998 h I Oregon Historic Trails Report Table of Contents . Executive summary 1 Project history 3 Introduction to Oregon’s Historic Trails 7 C Oregon’s National Historic Trails 11 C Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail 13 Oregon National Historic Trail 27 Applegate National Historic Trail 47 a Nez Perce National Historic Trail 63 C Oregon’s Historic Trails 75 Kiamath Trail, 19th Century 77 o Jedediah Smith Route, 1828 87 Nathaniel Wyeth Route, 1832/1834 99 C Benjamin Bonneville Route, 1833/1834 115 o Ewing Young Route, 1834/1837 129 Whitman Mission Route, 1841-1847 141 c Upper Columbia River Route, 1841-1851 167 John Fremont Route, 1843 183 o Meek Cutoff, 1845 199 o Cutoff to the Barlow Road, 1848-1884 217 Free Emigrant Road, 1853 225 o Santiam Wagon Road, 1865-1939 233 C General recommendations 241 Product development guidelines 243 Acknowledgements 247 4Xt C’ Executive summary C The Board of Directors and staff of the Oregon Trails Coordinating Council present the Oregon Historic Trails Report, the first step in the development of a statewide Oregon Historic C Trails Program. The Oregon Historic Trails Report is a general guide and planning document that will help future efforts to develop historic trail resources in Oregon. o The objective of the Oregon Historic Trails Program is to establish Oregon as the nation’s leader in developing historic trails for their educational, recreational, and economic values. The Oregon Historic Trails Program, when fully implemented, will help preserve and leverage C existing heritage resources while promoting rural economic development and growth through C heritage tourism.