Vol-10, No.1 (Myan to Chem)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lower Chindwin District Volume A

BURMA GAZETTEER LOWER CHINDWIN DISTRICT UPPER BURMA RANGOON OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT, GOVERNMENT PRINTING, BURMA TABLE OF CONTENTS. PAGE PART A. THE DISTRICT 1-211 Chapter I. Physical Description 1-20 Boundaries 1 The culturable portion 2 Rivers: the Chindwin; the Mu 3 The Alaungdaw gorge 4 Lakes ib. Diversity of the district ib. Area 5: Surveys ib. Geology 6 Petroliferous areas ib. Black-soil areas; red soils ib. Volcanic rocks 7 Explosion craters ib. Artesian wells 8 Saline efflorescence ib. Rainfall and climate 9 Fauna: quadrupeds; reptiles and lizards; game birds; predatory birds 9-15 Hunting: indigenous methods 16 Game fish 17 Hunting superstitions 18 Chapter II, History and Archæology 20-28 Early history 20 History after the Annexation of 1885 (a) east of the Chindwin; (b) west of the Chindwin: the southern portion; (c) the northern portion; (d) along the Chindwin 21-24 Archæology 24-28 The Register of Taya 25 CONTENTS. PAGE The Alaungdaw Katthapa shrine 25 The Powindaung caves 26 Pagodas ib. Inscriptions 27 Folk-lore: the Bodawgyi legend ib. Chapter III. The People 28-63 The main stock 28 Traces of admixture of other races ib. Population by census: densities; preponderance of females 29-32 Towns and large villages 32 Social and religious life: Buddhism and sects 33-35 The English Wesleyan Mission; Roman Catholics 35 Animism: the Alôn and Zidaw festivals 36 Caste 37 Standard of living: average agricultural income; the food of the people; the house; clothing; expenditure on works of public utility; agricultural stock 38-42 Agricultural indebtedness 42 Land values: sale and mortgage 48 Alienations to non-agriculturists 50 Indigence 51 Wages ib. -

Burmese Buddhist Imagery of the Early Bagan Period (1044 – 1113) Buddhism Is an Integral Part of Burmese Culture

Burmese Buddhist Imagery of the Early Bagan Period (1044 – 1113) 2 Volumes By Charlotte Kendrick Galloway A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University November 2006 ii Declaration I declare that to the best of my knowledge, unless where cited, this thesis is my own original work. Signed: Date: Charlotte Kendrick Galloway iii Acknowledgments There are a number of people whose assistance, advice and general support, has enabled me to complete my research: Dr Alexandra Green, Dr Bob Hudson, Dr Pamela Gutman, Dick Richards, Dr Tilman Frasch, Sylvia Fraser- Lu, Dr Royce Wiles, Dr Don Stadtner, Dr Catherine Raymond, Prof Michael Greenhalgh, Ma Khin Mar Mar Kyi, U Aung Kyaing, Dr Than Tun, Sao Htun Hmat Win, U Sai Aung Tun and Dr Thant Thaw Kaung. I thank them all, whether for their direct assistance in matters relating to Burma, for their ability to inspire me, or for simply providing encouragement. I thank my colleagues, past and present, at the National Gallery of Australia and staff at ANU who have also provided support during my thesis candidature, in particular: Ben Divall, Carol Cains, Christine Dixon, Jane Kinsman, Mark Henshaw, Lyn Conybeare, Margaret Brown and Chaitanya Sambrani. I give special mention to U Thaw Kaung, whose personal generosity and encouragement of those of us worldwide who express a keen interest in the study of Burma's rich cultural history, has ensured that I was able to achieve my own personal goals. There is no doubt that without his assistance and interest in my work, my ability to undertake the research required would have been severely compromised – thank you. -

Journals of Travels in Assam, Burma, Bhootan, Afghanistan and The

Journals of Travels in Assam, Burma, Bhootan, Afghanistan and The Neighbouring Countries 1 Journals of Travels in Assam, Burma, Bhootan, Afghanistan and The Neighbouring Countries The Project Gutenberg eBook, Journals of Travels in Assam, Burma, Bhootan, Afghanistan and The Neighbouring Countries, by William Griffith, Edited by John M'Clelland This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re−use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Journals of Travels in Assam, Burma, Bhootan, Afghanistan and The Neighbouring Countries Author: William Griffith Release Date: February 25, 2005 [eBook #15171] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO−646−US (US−ASCII) ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK JOURNALS OF TRAVELS IN ASSAM, BURMA, BHOOTAN, AFGHANISTAN AND THE NEIGHBOURING COUNTRIES*** This eBook was produced by Les Bowler from the 1847 edition. JOURNALS OF TRAVELS IN ASSAM, BURMA, BHOOTAN, AFGHANISTAN AND THE NEIGHBOURING COUNTRIES By William Griffith. Arranged by John M'Clelland. [Sketch of William Griffith: pf.jpg] CONTENTS. Notice of the author from the Proceedings of the Linnaean Society, and Extracts from Correspondence. CHAPTER IProceeding with the Assam Deputation for the Examination of the Tea Plant. II Journal of an Excursion in the Mishmee Mountains. III Tea localities in the Muttock Districts, Upper Assam. IV Journey from Upper Assam towards Hookum. V Journey from Hookum to Ava. VI Botanical Notes written in pencil, connected with the foregoing Chapter. Journals of Travels in Assam, Burma, Bhootan, Afghanistan and The Neighbouring Countries 2 VII General Report on the foregoing. -

Cowry Shells of Andrew Bay in Rakhine Coastal Region of Myanmar

Journal of Aquaculture & Marine Biology Research Article Open Access Cowry shells of Andrew Bay in Rakhine coastal region of Myanmar Abstract Volume 8 Issue 4 - 2019 A total of 21 species of cowry shells belonging to genus Cypraea Linnaeus 1758 of family Cypraeidae falling under the order Mesogastropoda collected from field observation in Naung Naung Oo 2014, were identified, using liquid-preserved materials and living specimens in the field, Department of Marine Science, Mawlamyine University, Myanmar based on the external characters of shell structures. The specimens comprised Cypraea tigris Linnaeus, 1758, C. miliaris Gmelin, 1791, C. mauritiana Linnaeus, 1758, C. thersites Correspondence: Naung Naung Oo, Assistant Lecturer, Department of Marine Science, Mawlamyine University, Myanmar, Gaskoin, 1849, C. arabica Linnaeus, 1758, C. scurra Gmelin, 1791, C. eglantina Duclos, Email 1833, C. talpa Linnaeus, 1758, C. argus Linnaeus, 1758, C. erosa Linnaeus, 1758, C. labrolineata Gaskoin, 1849, C. caputserpentis Linnaeus, 1758, C. nucleus Linnaeus, 1758, Received: July 06, 2019 | Published: August 12, 2019 C. isabella Linnaeus, 1758, C. cicercula Linnaeus, 1758, C. globulus Linnaeus, 1758, C. lynx Linnaeus, 1758, C. asellus Linnaeus, 1758, C. saulae Gaskoin, 1843, C. teres Gmelin, 1791 and C. reevei Gray, 1832. The distribution, habitats and distinct ecological notes of cowry shells in intertidal and subtidal zone of Andrew Bay and adjacent coastal areas were studied in brief. Keywords: andrew Bay, cowry shells, cypraeidae, gastropod, rakhine Coastal Region Introduction in the Western Central Pacific.17 There are Cypraea annulus Linnaeus, 1758; C. arabica Linnaeus, 1758; C. argus Linnaeus, 1758; C. bouteti The literature of the molluscs is vast in other countries but Burgess and Arnette, 1981; C. -

Writing Systems Reading and Spelling

Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems LING 200: Introduction to the Study of Language Hadas Kotek February 2016 Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Outline 1 Writing systems 2 Reading and spelling Spelling How we read Slides credit: David Pesetsky, Richard Sproat, Janice Fon Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems What is writing? Writing is not language, but merely a way of recording language by visible marks. –Leonard Bloomfield, Language (1933) Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems Writing and speech Until the 1800s, writing, not spoken language, was what linguists studied. Speech was often ignored. However, writing is secondary to spoken language in at least 3 ways: Children naturally acquire language without being taught, independently of intelligence or education levels. µ Many people struggle to learn to read. All human groups ever encountered possess spoken language. All are equal; no language is more “sophisticated” or “expressive” than others. µ Many languages have no written form. Humans have probably been speaking for as long as there have been anatomically modern Homo Sapiens in the world. µ Writing is a much younger phenomenon. Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems (Possibly) Independent Inventions of Writing Sumeria: ca. 3,200 BC Egypt: ca. 3,200 BC Indus Valley: ca. 2,500 BC China: ca. 1,500 BC Central America: ca. 250 BC (Olmecs, Mayans, Zapotecs) Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems Writing and pictures Let’s define the distinction between pictures and true writing. -

Financial Inclusion

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 I LIFT Annual Report 2020 ANNUAL REPORT 2020 II III LIFT Annual Report 2020 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ADB Asian Development Bank LBVD Livestock Breeding and Veterinary ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Department CBO Community-based Organisation We thank the governments of Australia, Canada, the European Union, LEARN Leveraging Essential Nutrition Ireland, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and CSO Civil Society Organisation Actions To Reduce Malnutrition project the United States of America for their kind contributions to improving the livelihoods and food security of rural poor people in Myanmar. Their DAR Department of Agricultural MAM Moderate acute malnutrition support to the Livelihoods and Food Security Fund (LIFT) is gratefully Research acknowledged. M&E Monitoring and evaluation DC Donor Consortium MADB Myanmar Agriculture Department of Agriculture Development Bank DISCLAIMER DoA DoF Department of Fisheries MEAL Monitoring, evaluation, This document is based on information from projects funded by LIFT in accountability and learning 2020 and supported with financial assistance from Australia, Canada, the DRD Department for Rural European Union, Ireland, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, the United Development MoALI Ministry of Agriculture, Kingdom, and the United States of America. The views expressed herein Livestock and Irrigation should not be taken to reflect the official opinion of the LIFT donors. DSW Department of Social Welfare MoE Ministry of Education Exchange rate: This report converts MMK into -

Developing Budalin Township of Sagaing Division Article: Kyawt Maung Maung; Photos: Tin Soe (Myanma Alin)

Established 1914 Volume XVII, Number 129 4th Waxing of Tawthalin 1371 ME Sunday, 23 August, 2009 Four political objectives Four economic objectives Four social objectives * Stability of the State, community peace * Development of agriculture as the base and all-round * Uplift of the morale and morality of development of other sectors of the economy as well and tranquillity, prevalence of law and the entire nation * Proper evolution of the market-oriented economic order * Uplift of national prestige and integ- system * National reconsolidation rity and preservation and safeguard- * Development of the economy inviting participation in * Emergence of a new enduring State ing of cultural heritage and national terms of technical know-how and investments from Constitution character sources inside the country and abroad * Building of a new modern developed * Uplift of dynamism of patriotic spirit * The initiative to shape the national economy must be kept * Uplift of health, fitness and education nation in accord with the new State in the hands of the State and the national peoples Constitution standards of the entire nation Developing Budalin Township of Sagaing Division Article: Kyawt Maung Maung; Photos: Tin Soe (Myanma Alin) Photo shows thriving Ngwechi-6 long staple cotton plantation in Budalin Township. Upon arrival at the entrance to Budalin recently, the news crew of Myanma Alin Daily saw the equestrian statue of Maha Bandoola that brings honour to the town. Located on the east bank of Chindwin River, Budalin is sharing border with Dabayin Township in the north, Ayadaw Township in the east, Monywa Township in the south and Yinmabin and Kani townships in the west. -

COUNCIL COMMON POSITION 2006/318/CFSP of 27 April 2006 Renewing Restrictive Measures Against Burma/Myanmar Having Regard To

29.4.2006EN Official Journal of the European Union L 116/77 COUNCIL COMMON POSITION 2006/318/CFSP of 27 April 2006 renewing restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, — the continued harassment of the NLD and other organised political movements, Having regard to the Treaty on European Union, and in particular Article 15 thereof, — the continuing serious violations of human rights, including the failure to take action to eradicate the use of forced labour in accordance with the recom- Whereas: mendations of the International Labour Organisa- tion's High-Level Team report of 2001 and recom- mendations and proposals of subsequent ILO Missions; and (1) On 26 April 2004, the Council adopted Common Position 2004/423/CFSP renewing restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar (1). These measures replaced the measures imposed by Common Position — 2003/297/CFSP (2), which had replaced the restrictive recent developments such as increasing restrictions measures initially adopted in 1996 (3). on the operation of international organisations and non-governmental organisations, (2) On 25 April 2005, the Council adopted Common Position 2005/340/CFSP extending restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar (4). These measures expire on the Council considers it fully justified to maintain the 25 April 2006. restrictive measures against the military regime in Burma/Myanmar, those who benefit most from its misrule, and those who actively frustrate the process of national reconciliation, respect for human rights and democracy. -

Title Around the Sagaing Township in Kon-Baung Period All Authors Moe

Title Around the Sagaing Township in Kon-baung Period All Authors Moe Moe Oo Publication Type Local Publication Publisher (Journal name, Myanmar Historical Research Journal, No-21 issue no., page no etc.) Sagaing Division was inhabited by Stone Age people. Sagaing town was a place where the successive kings of Pagan, Innwa and Kon-baungs period constructed religious buildings. Hence it can be regarded as an important place not only for military matters, but also for the administration of the kingdom. Moreover, a considerable number of foreigners were Siamese, Yuns and Manipuris also settled in Sagaing township. Its population was higher than that of Innwa and Abstract lower than that of Amarapura. Therefore, it can be regarded as a medium size town. Agriculture has been the backbone of Sagaing township’s economy since the Pagan period. The Sagaing must have been prosperous but the deeds of land and other mortgages highlight the economic difficulties of the area. It is learnt from the documents concerning legal cases that arose in this area. As Sagaing was famous for its silverware industry, silk-weaving and pottery, it can be concluded that the cultural status was high. Keywords Historical site, military forces, economic aspect, cultural heigh Citation Issue Date 2011 Myanmar Historical Research Journal, No-21, June 2011 149 Around the Sagaing Township in Kon-baung Period By Dr. Moe Moe Oo1 Background History Sagaing Division comprises the tracts between Ayeyarwady and Chindwin rivers, and the earliest fossil remains and remains of Myanmar’s prehistoric culture have been discovered there. A fossilized mandible of a primate was discovered in April 1978 from the Pondaung Formation, a mile to the northwest of Mogaung village, Pale township, Sagaing township. -

Ie, I Oung-Hill, and Noo-Nah? Leprosy? Refer

UPPER BURMA. 53 Feb., 1906.] YAWS IN The of these are riverine villages be- REPORT ON THE PREVALENCE OF YAWS majority tween which constant communication ?exists IN THE LOWER CHINDWIN DISTRICT, Inland villages in this township are less affected UPPER BURMA. and in farther inland ones some distance from each the disorder to a slight by p. a. other, prevails only ? McCarthy, extent. Mily. Asst.-Sdbgeon, Budalin township adjoining Kani has also 29 Civil Surgeon, Lower Chinchoin District. villages where the disease is found. The majo- was of are on I he existence of yaws in the district rity these villages the Chindwin river with first Mr. A. H. Nolan, late Civil in communication villages in the Kani recognised bj7 have also of Monywa, who had his attention township. Oases been seen in some Surgeon on the Mu drawn to cases of the disease in the small villages river near the Sliwebo previously district. Pakokku and Shwebo districts in 1899. After border of the the dis- In Alon township the disease is found in his appointment to Lower Chindwin were seen to those 6 in one villas trict, cases which similar only villages, Salingyi township is while Pale is found in Shwebo and Pakokku districts, led to affected ; entirely free from ft and ? an and study of the disorder found Character description of the disease. enquiry The observations have been made prevailing in this district. His observations following be- from a of 431 cases that have been were embodied in a paper which was read study treated m the from November fore the Indian Medical Congress in Calcutta district 1904. -

TRENDS in SAGAING Photo Credits

Local Governance Mapping THE STATE OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS IN SAGAING Photo Credits William Pryor Mithulina Chatterjee Myanmar Survey Research The views expressed in this publication are those of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views of UNDP. Local Governance Mapping THE STATE OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS IN SAGAING UNDP MYANMAR The State of Local Governance: Trends in Sagaing - UNDP Myanmar 2015 Table of Contents Acknowledgements II Acronyms III Executive summary 1 - 3 1. Introduction 4 - 5 2. Methodology 6 - 8 3. Sagaing Region overview and regional governance institutions 9 - 24 3.1 Geography 11 3.2 Socio-economic background 11 3.3 Demographic information 12 3.4 Sagaing Region historical context 14 3.5 Representation of Sagaing Region in the Union Hluttaws 17 3.6 Sagaing Region Legislative and Executive Structures 19 3.7 Naga Self-Administered Zone 21 4. Overview of the participating townships 25 - 30 4.1 Introduction to the townships 26 4.1.1 Kanbalu Township 27 4.1.2 Kalewa Township 28 4.1.3 Monywa Township 29 4.1.4 Lahe Township (in the Naga SAZ) 30 5. Governance at the frontline – participation in planning, responsiveness for local service provision, and accountability in Sagaing Region 31- 81 5.1 Development planning and participation 32 5.1.1 Planning Mechanisms 32 5.1.2 Citizens' perspectives on development priorities 45 5.1.3 Priorities identified at the township level 49 5.2 Basic services - access and delivery 50 5.2.1 General Comments on Service Delivery 50 5.2.2 Health Sector Services 50 5.2.3 Education Sector Services 60 5.2.4 Drinking Water Supply Services 68 5.3 Transparency and accountability 72 5.3.1 Citizens' knowledge of governance structures 72 5.3.2 Citizen access to information relevant to accountability 76 5.3.3 Safe, productive venues for voicing opinions 79 6. -

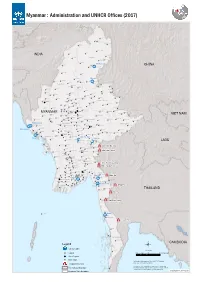

Myanmar : Administration and UNHCR Offices (2017)

Myanmar : Administration and UNHCR Offices (2017) Nawngmun Puta-O Machanbaw Khaunglanhpu Nanyun Sumprabum Lahe Tanai INDIA Tsawlaw Hkamti Kachin Chipwi Injangyang Hpakan Myitkyina Lay Shi Myitkyina CHINA Mogaung Waingmaw Homalin Mohnyin Banmauk Bhamo Paungbyin Bhamo Tamu Indaw Shwegu Momauk Pinlebu Katha Sagaing Mansi Muse Wuntho Konkyan Kawlin Tigyaing Namhkan Tonzang Mawlaik Laukkaing Mabein Kutkai Hopang Tedim Kyunhla Hseni Manton Kunlong Kale Kalewa Kanbalu Mongmit Namtu Taze Mogoke Namhsan Lashio Mongmao Falam Mingin Thabeikkyin Ye-U Khin-U Shan (North) ThantlangHakha Tabayin Hsipaw Namphan ShweboSingu Kyaukme Tangyan Kani Budalin Mongyai Wetlet Nawnghkio Ayadaw Gangaw Madaya Pangsang Chin Yinmabin Monywa Pyinoolwin Salingyi Matman Pale MyinmuNgazunSagaing Kyethi Monghsu Chaung-U Mongyang MYANMAR Myaung Tada-U Mongkhet Tilin Yesagyo Matupi Myaing Sintgaing Kyaukse Mongkaung VIET NAM Mongla Pauk MyingyanNatogyi Myittha Mindat Pakokku Mongping Paletwa Taungtha Shan (South) Laihka Kunhing Kengtung Kanpetlet Nyaung-U Saw Ywangan Lawksawk Mongyawng MahlaingWundwin Buthidaung Mandalay Seikphyu Pindaya Loilen Shan (East) Buthidaung Kyauktaw Chauk Kyaukpadaung MeiktilaThazi Taunggyi Hopong Nansang Monghpyak Maungdaw Kalaw Nyaungshwe Mrauk-U Salin Pyawbwe Maungdaw Mongnai Monghsat Sidoktaya Yamethin Tachileik Minbya Pwintbyu Magway Langkho Mongpan Mongton Natmauk Mawkmai Sittwe Magway Myothit Tatkon Pinlaung Hsihseng Ngape Minbu Taungdwingyi Rakhine Minhla Nay Pyi Taw Sittwe Ann Loikaw Sinbaungwe Pyinma!^na Nay Pyi Taw City Loikaw LAOS Lewe