Mother, Memory, Monotony Joshua Osborn a Thesis Submitted in Partial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Separate Cells by David Erdos.Pdf

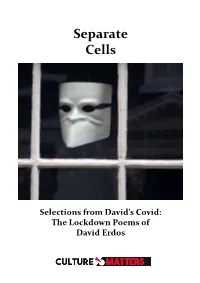

Separate Cells Selections from David’s Covid: The Lockdown Poems of David Erdos David Erdos is a vital part of our 21st century counter-cultural connectome, skittering across the literary landscape like a bead of mercury and leaving freshly-soldered synaptic linkages in his wake. If it’s a matter of importance, synthesis, or beauty, then Erdos is there to document, dissect and celebrate: an enthralling chatterbox of the human condition. —Alan Moore David Erdos is the good detective, out there, on the move, on the case. He is a positive energy, a sympathetic reporter and recorder. Follow him. I marvel over the velocity and production of David Erdos’ poems. He is out there now, high among the ranks of the great, but unappreciated —Iain Sinclair As psycho-geographer of the zeitgeist David Erdos has a rich hinterland to draw upon, being himself poet, actor, director, composer, illustrator, musician and critic. The reader soon learns that the writer is well informed on very many levels and that he’s in safe hands for what proves to be a rewarding, penetrating and often breath-taking ride. —Heathcote Williams Counterculture becomes even more important in these times of no cultural margins and constant erasure, making its dwindling list of commentators all the more crucial. There is no questioning the importance of David Erdos’ contribution as he includes me in his canon. Quite possibly the greatest living cultural commentator since Cyril Connolly! —Chris Petit My heart pulses with the essence of David’s poetry taking me away from the normal and casting each haunting image into an underworld of possibility —Clare Nasir David Erdos brings light to the back alleys and side streets of culture and reveals so much gold that you have to question what it is that more mainstream critics do with their days. -

RD 071 937 SO 005 072 AUTHOR Payne, Judy Reeder TITLE Introduction to Eastern Philosophy, :Jocial Studies: 6414.23

DOCIDIENT RESUME RD 071 937 SO 005 072 AUTHOR Payne, Judy Reeder TITLE Introduction to Eastern Philosophy, :Jocial Studies: 6414.23. INSTITUTION Dade County Public Schools, Miami, Fla. PUB DATE 71 NOTE 39p.; An Authorized course of instruction for the Quinmester Program EDRS PRICE MF -S0.65 HC -93.29 DESCRIPTORS Activity Units; Asian Studies; Behay.aral Objectives; Chinese Culture; Curriculum Guides; Grade 10; Grade 11; Grade 12; *Non Western Civilization; *Philosophy; *Religion; Resource Units; Secondary Grades; *Social Studies Units; Values IDENTIFIERS Flcrida; *Quinmester Program ABSTRACT Major Eastern philosophies and/or religions col sisting of Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, and Shintoism are investigated by 10th through 12th grade students in this general social studies quinmester course. Since Eastern philosophical ideas are already influencing students, this course aims to guide students in a universal search for values and beliefs about the meaning of life. Through suggested activity learning, the five major religions are compared and contrasted for their differences, similarities, and .are examined for their influences upon Non Western and Western civilizations. Lastly, students trace contemporary ideas to Eastern philosophies. The course is arranged, as are other quinmester courses, with sections on broad goals, course content, activities, and materials. (SJM) AUTHORIZED COURSE OF INSTRUCTION FOR THE Uo Vlige1/45) 0 O Spcial Studies : INTRODUCTION TO EASTERNPHILOSOPHY 64111.23 6448.69 DIVISION OF INSTRUCTION1971 ED 071937 SOCIAL STUDIES INTRODUCTION TO EASTERN PHILOSOPHY zwoom5,13,0-mmmMZ17,MmMgg25.±:1"21'zmy., -omc 6448.696414.23 mmzocon>owao5zar4o--4m-5).35o5mt7zom74oviSollAmstwoz.3:14mm_pm..'mo mzsimmZ .momoo5,7,09c JUDY REEDERby PAYNE CmzQrfi7!!400z0m'10'.00m:;CS-,.740Olapm zMrsg;,T,m, for the 517,ZE5c00,m2.00'T23-DOM OM 2..I DadeDivision CountyMiami, 1971of PublicFloridaInstruction Schools DADE COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD Mr. -

Manchester Historical Society

- \ . , 1- . , PAGE TWENTY - EVENING HERALD, Thurs.. May 24, 1979 —N Source comparative 'tar' and nicotine figures: FTC Report May 1978. r--------- ^ Of All Brands Sold: Lowest tan 0.5 mg.'tar,' 0.05 mg. nicotine av. per cigarette. 1 Bystander Takes Movie I Orioles Red Hot Golden Lights: Regular 8i M enthol— 8 mg.'tar,' 0.7 mg. nicotine av. per cigarette by FTC Method. Warning: The Surgeon General Has Determined Area HMO Starts Work 1 TV Spin-Off Syndrome That Cigarette Smoking Is Dangerous to Your Health. For New Health Center Growing in the 1980s 1 Of Robbery in Vermont 1 As Red Sox Learn Page 2 Page 10 1 Page 1 2 1 Page 13 L 1 Cloudy, Showers Through Saturday Details .on page 2 Coal Standards Vol. XCVIII, No. 200 — Manchester, Conn., Friday, May 25,1979 a A Family NEWSpaper Since 1881 • 20C Single Copy • 15$ Home Delivered WASHINGTON (UPI) - The Environmental Protection Agen cy today announced strict emis sion standards for new coal-fired power plants and said they will cost $35 billion but will clear the Gas Prices air of acid rain after the turn of the century. The standards apply to all new power plants for which' construc tion began after Sept. 18, 1978. The proposal is believed to be Spark Rise one of the most costly ever proposed by the EPA, but ad ministrator Douglas Costle said it is necessary to protect health and environment in light of the ad In Inflation ministration’s plan to triple coal use and production to meet the WASHINGTON (UPI) - Gasoline cent. -

Lands of Intrigue: Castle Spulzeer Builder's Guide

Lands of Intrigue: Castle Spulzeer Builder's Guide a Neverwinter Nights 1 Module by Erick “Alleyslink” Horton Based on Lands of Intrigue: Book 2 by Steven E. Schend & Castle Spulzeer by Doug Stewart TABLE OF CONTENTS Clink link for section's Table of Contents Prelude Guilds Chapters Key Concepts Story Arcs Henchmen TOC > Prelude The Unfortunate House of Spellseer The Possession of Xvim TOC > Guilds Temple of Major Cargunn's the Black Hand Mercenary Cowled Wizards (Bane) Guild Tower of Duskwood Dell Golden Fortress Willful Suffering (Ilmater) Tower of the Twisted Rune Shadow Thieves Vengeful Hand (Tempus) TOC > Chapters Chapter 1: Chapter 2: Chapter 3: Encounter in Eshpurta The South Road Hillfort Kelsha Chapter 4a: Chapter 4b: Chapter 5a: Skullgnasher Route Overland Route Trailstone Chapter 5b: Chapter 5c: Chapter 5d: Twin Towers of the Eternal Eclipse Cave of Wonders Rebels of Riatavin Chapter 5e: Chapter 5f: Chapter 6: Sunrise Orchid Orgoth's Tower Castle Spulzeer Chapter Thirteen TOC > Prelude: The Unfortunate House of Spellseer 1 2 3 An ancient, rich, powerful and wicked Some family left and founded Trailstone Chardath Spulzeer, current occupant, and family named Spellseer lived on the Amn others remained in the family castle, which Marble, his deaf mute sister recently and Tethyr Border. Horse trading made they converted to an inn catering to rich abode in the Castle. Kartak, plotting to their fortune, aided by family members' travelers with perverted tastes. Kartak kept once more encase his spirit in flesh, innate magical abilities. a secret chamber in the castle and there he mentally compelled Chardath to sacrifice hid his phylactery. -

Rajasthan Tour Itinerary V. 5

Exclusive Tour of the Music, Dance and Spiritual Worlds of Rajasthan, India 2016 With Yuval Ron & Sajida Ben-Tzur Take a journey full of rare musical encounters, exquisite dancing, sacred Sufi shrines, stunning landscapes, temples, desert tribal parties and the festive celebrations of Rajasthan 14 glorious days - February 14-27, 2016 The sights of India’s impressive landscapes are the glorious backdrop for a special excursion that enables an intimate, unique introduction to India through its tribal musical culture and the special inhabitants of the Rajasthan desert. Rajasthan (Raj – royal, sthan – land/state) is one of the most colorful states in India. It is a desert region abounding in classical and ancient traditions, where palaces, temples, fortresses and royalty exist alongside villages and tribes. Music in India, and especially in Rajasthan, is a principal part of religious rituals setting the tone for holidays and wedding ceremonies. This music, played for kings when they went off to battle, accompanies the Sufi festivities and provides entertainment for the high society. Bringing the various religions and classes together, the music of Rajasthan opens a door to the fascinating cultural worlds that are the focus and inspiration for this special journey. Sajida Ben-Tzur, our tour guide, is a dancer of Kathak classical Indian and the Rajasthani folk dance traditions, an Indian Chef and the daughter of a Sufi Sheikh from Rajasthan. Sajida (pronounced SAJ-DA) has met and worked with many of the most exceptional musicians in this region. This tour facilitates a personal connection with Rajasthan’s landscapes and people through the ears, the eyes and especially the heart! Feb 14-15, 2016 - Day 1-2: Flight to India Depart on a flight of your choice to Delhi, India. -

Bees in the Garden: Poems by the Masala Mystic

BEES IN THE GARDEN POEMS BY THE MASALA MYSTIC Edited by Henry Rasof Poems by the Masala Mystic © 2019 by Henry Rasof 1 BEES IN THE GARDEN POEMS BY THE MASALA MYSTIC View of Varanasi (at one time called Benares or Banaras), the holiest Indian city, from the Ganges, the holiest Indian river. The cloudy air probably includes smoke from the many cremations that take place along the banks of the river. I say "probably," because it also is possible that the hazy air is a kind of physical metaphor for maya, the veil of illusion that the Masala Mystic writes about in many of his poems. If you are cremated in Varanasi, it is said that you will not be reincarnated on Earth. Poems by the Masala Mystic © 2019 by Henry Rasof 2 BEES IN THE GARDEN POEMS BY THE MASALA MYSTIC I give my poetry away, and give myself along with it But first I look for people who can value what I give. —Mirza Ghalib Mirza Ghalib Edited by Henry Rasof TEMESCAL CANYON PRESS Louisville, CO 2019 Poems by the Masala Mystic © 2019 by Henry Rasof 3 Books of Original Poetry by the Editor Souls in the Garden: Poems About Jewish Spain (2019) Here I Seek You: Jewish Poems for Shabbat, Holy Days, and Everydays (2016) Chance Music: Prose Poems 1974 to 1982 (2012) The House (2009) Web Sites by the Editor henryrasof.com www.medievalhebrewpoetry.org copyright © 2019 by Henry Rasof All rights reserved. No photograph, regardless of the source, may be reproduced, copied, transmitted, or linked to in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage or retrieval system. -

Journal of Stevenson Studies Volume 13 Ii Journal of Stevenson Studies Journal of Stevenson Studies Iii

Journal of Stevenson Studies Volume 13 ii Journal of Stevenson Studies Journal of Stevenson Studies iii Editors Professor Linda Dryden Professor Emeritus CLAW Roderick Watson School of Arts and Creative School of Arts and Industries Humanities Napier University University of Stirling Craighouse Stirling Edinburgh FK9 4LA EH10 5LG Scotland Scotland Email: Tel: 0131 455 6128 [email protected] Email: [email protected] Contributions to volume 14 are warmly invited and should be sent to either of the editors listed above. The text should be submitted in MS WORD files in MHRA format. All contribu- tions are subject to review by members of the Editorial Board. Published by The Centre for Scottish Studies University of Stirling © The contributors 2016 ISSN: 1744-3857 Printed and bound in the UK by Antony Rowe Ltd. Chippenhan, Wiltshire. iv Journal of Stevenson Studies Editorial Board Professor Richard Ambrosini Professor Penny Fielding Universita’ di Roma Tre Department of English Rome University of Edinburgh Professor Stephen Arata Professor Gordon Hirsch School of English Department of English University of Virginia University of Minnesota Dr Hilary Beattie Professor Barry Menikoff Department of Psychiatry Department of English Columbia University University of Hawaii at Manoa Professor Oliver Buckton Professor Glenda Norquay School of English Department of English and Florida Atlantic University Cultural History Liverpool John Moores Professor Linda Dryden University School of Arts and Creative Industries Professor Roderick Watson Edinburgh -

Studio Dragon (253450) Update Long -Awaited Good News

2019. 11. 22 Company Studio Dragon (253450) Update Long -awaited good news ● Studio Dragon yesterday inked a three-years strategic deal with Netflix, in which Minha Choi the: 1) latter will purchase 4.99% of the Korean firm within a year; and 2) former will Analyst provide the US distributor with at least 21 productions starting from next year. [email protected] ● The partnership should allow Studio Dragon to: 1) produce dramas stably before 822 2020 7798 other global OTT platforms enter Korea or make inroads elsewhere in Asia; and 2) Kwak Hoin enjoy margin growth for its content production and distribution rights sale. Research Associate [email protected] ● We keep the stock as our sector top pick on expectations of its overseas 822 2020 7763 expansion gathering pace. WHAT’S THE STORY? Deal with Netflix...: CJ ENM, Studio Dragon, and Netflix yesterday announced that they had entered a multi-year strategic partnership, under which: 1) CJ ENM can sell up to 4.99% [roughly 1.4m shares] of Studio Dragon to Netflix within a year; 2) Studio Dragon will provide at least 21 original series productions to Netflix, along with their distribution rights sales, for three years starting in 2020. Per-show and distribution rights prices will be determined case by case, while titles are to be selected from a library of IP rights owned by Studio Dragon and distribution rights held by CJ ENM. AT A GLANCE … boasts several positives: This deal will give Studio Dragon stability as it provides Netflix with drama productions for at least three years, while the US firm’s massive budget should help those shows compete worldwide. -

D , Honolulu Weekly

n the surface, it looks like That's the way the debate over the a classic political show state's homeless village plan is being The Wolf in down. On one side: The portrayed. But there are too many Smokey state government with a loose ends, unasked questions and heart, aggressively slash disquieting hints to accept this inter bythe Sheep's Clothing ing through a jungle of red pretation at face value. I can't help tape to build a series of asking, "What's wrong with this pic "viIJages" to shelter the homeless. ture?" Sea Is the state'shomeless plan a On the other: An array of appar Earlier in the summer, the gov 3 ently selfish property owners, ernment that cares aboutthe home frontfor development interests? NIMBYsout to protect_allthat they less sent in police and bulJdozers to illlllllllB have accumulated in their own take care of families whb had the By Ian Lind backyards. Artist in Attic 7 \ Rocks ofAges Volume 1, Issue 9, September 11, 1991 11 Every- �I lhing You Always wanted toKnow About Sumo· ) • I I I I � L��(/ ,.----� --- -- ... Mauka to Makai public discussions of the controver their neighborho�s or on land use Continuedfrom Page 1 sial plan and refusingeven to appear laws, while they pointedlyignore the Not your audacity to build their own shelters publicly or to be photographed. whole speculative real estate system near the beach at Anahola without Most ominous, in the long term, that has benefitedpolitical insiders in the benefit of charity. I remember are the increasing number of com Hawaii foryears. -

Stream Media Corporation / 4772

Stream Media Corporation / 4772 COVERAGE INITIATED ON: 2021.07.20 LAST UPDATE: 2021.07.20 Shared Research Inc. has produced this report by request from the company discussed in the report. The aim is to provide an “owner’s manual” to investors. We at Shared Research Inc. make every effort to provide an accurate, objective, and neutral analysis. In order to highlight any biases, we clearly attribute our data and findings. We will always present opinions from company management as such. Our views are ours where stated. We do not try to convince or influence, only inform. We appreciate your suggestions and feedback. Write to us at [email protected] or find us on Bloomberg. Research Coverage Report by Shared Research Inc. Stream Media Corporation/ 4772 RCoverage LAST UPDATE: 2021.07.20 Research Coverage Report by Shared Research Inc. | https://sharedresearch.jp INDEX How to read a Shared Research report: This report begins with the trends and outlook section, which discusses the company’s most recent earnings. First-time readers should start at the business section later in the report. Executive summary ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Key financial data ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 Recent updates ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

0 M Thalos Lead Philos 73—48

i ^ m WEATHER, | || EUREKA JAMBOREE [Ucj jjje Si FAIR and WARMER i® 0 SATURDAY, OCT. 8th ^nl 31 --OF- TAYLOR UNIVERSITY VOLUME XV. UPLAND, INDIANA, WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 5, 1927 NUMBER 3 Thalos Lead Philos 73—48 LATEST OFFICIAL FIGURES ON RESULTS Two Great Missionary OF RUSH DAY SHOW Programs of High Merit THE THALOS WITH A Sermons Heard Sunday LEAD OF 25 OVER THEIR RIVALS THEPresented to T,U, Audiences Dr. Rockwell Clancy From India Speaks at Chapel. PHILOS. Dr. Canright of China Speaks at the M. E. Church. THIS COUNT IS PRACTI PHILOS DRAW LARGE CROWDS THALO PROGRAM AN ARTISTIC AT OPENING PROGRAM MARVEL CALLY FINAL WITH ONLY WELL KNOWN ARTISTS A Day Of Missionary Feasting For T, U. A VERY FEW OF THE NEW PARTICIPATE "A DREAM OF YOUTH"' was the STUDENTS UNACCOUNTED theme of the program Saturday ev Taylor and vicinity were favored FOR. An exceptional range of talent of ening. Amid a setting of artistic beau with a feast Sunday when two great Dr, Clancy Speaks InP, M. the highest order, rendered amid a ty the Thalonian Literary Society missionaries gave stirring messages, setting of superb and almost breath presented to a Taylor audience one Christ is responsible for the great representing practically one half of taking beauty was the feature of the of the finest programs in the last revolutions going on in Asia toady. the world. Dr* Paul Preaches Philo program of Friday night, Sept. several years Speaking of India before the after 30. From begining to end it was well __Dr. Canright has spent the best Allen presented a silver loving noon Chapel service, Dr. -

Beyond Holy Russia: the Life and Times of Stephen Graham

Beyond Holy Russia MICHAEL The Life and Times HUGHES of Stephen Graham To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/217 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. BEYOND HOLY RUSSIA The Life and Times of Stephen Graham Michael Hughes www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Michael Hughes This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Hughes, Michael, Beyond Holy Russia: The Life and Times of Stephen Graham. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0040 Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders; any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available from our website at: http://www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781783740123 ISBN Paperback: 978-1-78374-012-3 ISBN Hardback: 978-1-78374-013-0 ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-78374-014-7 ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 978-1-78374-015-4 ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 978-1-78374-016-1 DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0040 Cover image: Mikhail Nesterov (1863-1942), Holy Russia, Russian Museum, St Petersburg.