Journal of Stevenson Studies Volume 13 Ii Journal of Stevenson Studies Journal of Stevenson Studies Iii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRAVEL and ADVENTURE in the WORKS of ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON by Mahmoud Mohamed Mahmoud Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department

TRAVEL AND ADVENTURE IN THE WORKS OF ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON by Mahmoud Mohamed Mahmoud Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Scottish Literature University of Glasgow. JULY 1984 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my deepest sense of indebtedness and gratitude to my supervisor, Alexander Scott, Esq., whose wholehearted support, invaluable advice and encouragement, penetrating observations and constructive criticism throughout the research have made this work possible; and whose influence on my thinking has been so deep that the effects, certainly, will remain as long as I live. I wish also to record my thanks to my dear wife, Naha, for her encouragement and for sharing with me a considerable interest in Stevenson's works. Finally, my thanks go to both Dr. Ferdous Abdel Hameed and Dr. Mohamed A. Imam, Department of English Literature and Language, Faculty of Education, Assuit University, Egypt, for their encouragement. SUMMARY In this study I examine R.L. Stevenson as a writer of essays, poems, and books of travel as well as a writer of adventure fiction; taking the word "adventure" to include both outdoor and indoor adventure. Choosing to be remembered in his epitaph as the sailor and the hunter, Stevenson is regarded as the most interesting literary wanderer in Scottish literature and among the most intriguing in English literature. Dogged by ill- health, he travelled from "one of the vilest climates under heaven" to more congenial climates in England, the Continent, the States, and finally the South Seas where he died and was buried. Besides, Stevenson liked to escape, especially in his youth, from the respectabilities of Victorian Edinburgh and from family trouble, seeking people and places whose nature was congenial to his own Bohemian nature. -

Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson Adapted by Bryony Lavery

TREASURE ISLAND BY ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON ADAPTED BY BRYONY LAVERY DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. TREASURE ISLAND Copyright © 2016, Bryony Lavery All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of TREASURE ISLAND is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan- American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for TREASURE ISLAND are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No professional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., and paying the requisite fee. Inquiries concerning all other rights should be addressed to United Agents, 12-26 Lexington Street, London, England, W1F 0LE. -

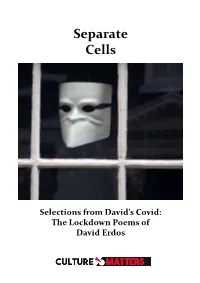

Separate Cells by David Erdos.Pdf

Separate Cells Selections from David’s Covid: The Lockdown Poems of David Erdos David Erdos is a vital part of our 21st century counter-cultural connectome, skittering across the literary landscape like a bead of mercury and leaving freshly-soldered synaptic linkages in his wake. If it’s a matter of importance, synthesis, or beauty, then Erdos is there to document, dissect and celebrate: an enthralling chatterbox of the human condition. —Alan Moore David Erdos is the good detective, out there, on the move, on the case. He is a positive energy, a sympathetic reporter and recorder. Follow him. I marvel over the velocity and production of David Erdos’ poems. He is out there now, high among the ranks of the great, but unappreciated —Iain Sinclair As psycho-geographer of the zeitgeist David Erdos has a rich hinterland to draw upon, being himself poet, actor, director, composer, illustrator, musician and critic. The reader soon learns that the writer is well informed on very many levels and that he’s in safe hands for what proves to be a rewarding, penetrating and often breath-taking ride. —Heathcote Williams Counterculture becomes even more important in these times of no cultural margins and constant erasure, making its dwindling list of commentators all the more crucial. There is no questioning the importance of David Erdos’ contribution as he includes me in his canon. Quite possibly the greatest living cultural commentator since Cyril Connolly! —Chris Petit My heart pulses with the essence of David’s poetry taking me away from the normal and casting each haunting image into an underworld of possibility —Clare Nasir David Erdos brings light to the back alleys and side streets of culture and reveals so much gold that you have to question what it is that more mainstream critics do with their days. -

The Dracula Film Adaptations

DRACULA IN THE DARK DRACULA IN THE DARK The Dracula Film Adaptations JAMES CRAIG HOLTE Contributions to the Study of Science Fiction and Fantasy, Number 73 Donald Palumbo, Series Adviser GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Recent Titles in Contributions to the Study of Science Fiction and Fantasy Robbe-Grillet and the Fantastic: A Collection of Essays Virginia Harger-Grinling and Tony Chadwick, editors The Dystopian Impulse in Modern Literature: Fiction as Social Criticism M. Keith Booker The Company of Camelot: Arthurian Characters in Romance and Fantasy Charlotte Spivack and Roberta Lynne Staples Science Fiction Fandom Joe Sanders, editor Philip K. Dick: Contemporary Critical Interpretations Samuel J. Umland, editor Lord Dunsany: Master of the Anglo-Irish Imagination S. T. Joshi Modes of the Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Twelfth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Robert A. Latham and Robert A. Collins, editors Functions of the Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Thirteenth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Joe Sanders, editor Cosmic Engineers: A Study of Hard Science Fiction Gary Westfahl The Fantastic Sublime: Romanticism and Transcendence in Nineteenth-Century Children’s Fantasy Literature David Sandner Visions of the Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Fifteenth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Allienne R. Becker, editor The Dark Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Ninth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts C. W. Sullivan III, editor Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Holte, James Craig. Dracula in the dark : the Dracula film adaptations / James Craig Holte. p. cm.—(Contributions to the study of science fiction and fantasy, ISSN 0193–6875 ; no. -

Journal of Stevenson Studies

1 Journal of Stevenson Studies 2 3 Editors Dr Linda Dryden Professor Roderick Watson Reader in Cultural Studies English Studies Faculty of Art & Social Sciences University of Stirling Craighouse Stirling Napier University FK9 4La Edinburgh Scotland Scotland EH10 5LG Scotland Tel: 0131 455 6128 Tel: 01786 467500 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Contributions to future issues are warmly invited and should be sent to either of the editors listed above. The text should be submitted in MS WORD files in MHRA format. All contributions are subject to review by members of the Editorial Board. Published by The Centre for Scottish Studies University of Stirling © the contributors 2005 ISSN: 1744-3857 Printed and bound in the UK by Antony Rowe Ltd. Chippenham, Wiltshire. 4 Journal of Stevenson Studies Editorial Board Professor Richard Ambrosini Professor Gordon Hirsch Universita’ de Roma Tre Department of English Rome University of Minnesota Professor Stephen Arata Professor Katherine Linehan School of English Department of English University of Virginia Oberlin College, Ohio Professor Oliver Buckton Professor Barry Menikoff School of English Department of English Florida Atlantic University University of Hawaii at Manoa Dr Jenni Calder Professor Glenda Norquay National Museum of Scotland Department of English and Cultural History Professor Richard Dury Liverpool John Moores University of Bergamo University (Consultant Editor) Professor Marshall Walker Department of English The University of Waikato, NZ 5 Contents Editorial -

Chapter Five: a Gentleman from France

CHAPTER FIVE A Gentleman From France THE boom of naval gunnery rolled like thunder off the hills behind Vailima. Louis could feel each concussion as he sat writing in his study beside a locked stand of loaded rifles. With these the household was supposed to defend itself if attacked by natives during the civil war that had broken out in Samoa. It had been a gory business, with heads taken on both sides, but so far Louis’s extended family had escaped harm. He knew and loved many of the Samoans taking part, and despised the Colonial governors whose incompetence had led to this fiasco, yet he felt curiously detached from it all. The men on board HMS Curacoa, now engaged in shelling a small fort full of Samoan rebels, were his friends. Whenever any naval vessel put in at Apia, Louis liked to offer the men rest and recreation at Vailima, with a Samoan feast. In return he had been welcomed on board the Curacoa and taken out on naval manoeuvres to see how Victorian marine engineering and a well-drilled crew combined to create an invincible fighting machine, whose firepower was now directed at his other, Samoan friends cowering within the stockade, their small arms and war clubs useless against a British dreadnought. They, too, had been welcome guests at Vailima, where ‘Tusitala’ (the storyteller) was always willing to interrupt his writing to entertain native chiefs and their entourages. For them each Boom! now spelled pain and death, yet Louis could not wring his hands. He had done his best to avoid this small colonial tragedy, and destiny must take its course. -

RD 071 937 SO 005 072 AUTHOR Payne, Judy Reeder TITLE Introduction to Eastern Philosophy, :Jocial Studies: 6414.23

DOCIDIENT RESUME RD 071 937 SO 005 072 AUTHOR Payne, Judy Reeder TITLE Introduction to Eastern Philosophy, :Jocial Studies: 6414.23. INSTITUTION Dade County Public Schools, Miami, Fla. PUB DATE 71 NOTE 39p.; An Authorized course of instruction for the Quinmester Program EDRS PRICE MF -S0.65 HC -93.29 DESCRIPTORS Activity Units; Asian Studies; Behay.aral Objectives; Chinese Culture; Curriculum Guides; Grade 10; Grade 11; Grade 12; *Non Western Civilization; *Philosophy; *Religion; Resource Units; Secondary Grades; *Social Studies Units; Values IDENTIFIERS Flcrida; *Quinmester Program ABSTRACT Major Eastern philosophies and/or religions col sisting of Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, and Shintoism are investigated by 10th through 12th grade students in this general social studies quinmester course. Since Eastern philosophical ideas are already influencing students, this course aims to guide students in a universal search for values and beliefs about the meaning of life. Through suggested activity learning, the five major religions are compared and contrasted for their differences, similarities, and .are examined for their influences upon Non Western and Western civilizations. Lastly, students trace contemporary ideas to Eastern philosophies. The course is arranged, as are other quinmester courses, with sections on broad goals, course content, activities, and materials. (SJM) AUTHORIZED COURSE OF INSTRUCTION FOR THE Uo Vlige1/45) 0 O Spcial Studies : INTRODUCTION TO EASTERNPHILOSOPHY 64111.23 6448.69 DIVISION OF INSTRUCTION1971 ED 071937 SOCIAL STUDIES INTRODUCTION TO EASTERN PHILOSOPHY zwoom5,13,0-mmmMZ17,MmMgg25.±:1"21'zmy., -omc 6448.696414.23 mmzocon>owao5zar4o--4m-5).35o5mt7zom74oviSollAmstwoz.3:14mm_pm..'mo mzsimmZ .momoo5,7,09c JUDY REEDERby PAYNE CmzQrfi7!!400z0m'10'.00m:;CS-,.740Olapm zMrsg;,T,m, for the 517,ZE5c00,m2.00'T23-DOM OM 2..I DadeDivision CountyMiami, 1971of PublicFloridaInstruction Schools DADE COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD Mr. -

Manchester Historical Society

- \ . , 1- . , PAGE TWENTY - EVENING HERALD, Thurs.. May 24, 1979 —N Source comparative 'tar' and nicotine figures: FTC Report May 1978. r--------- ^ Of All Brands Sold: Lowest tan 0.5 mg.'tar,' 0.05 mg. nicotine av. per cigarette. 1 Bystander Takes Movie I Orioles Red Hot Golden Lights: Regular 8i M enthol— 8 mg.'tar,' 0.7 mg. nicotine av. per cigarette by FTC Method. Warning: The Surgeon General Has Determined Area HMO Starts Work 1 TV Spin-Off Syndrome That Cigarette Smoking Is Dangerous to Your Health. For New Health Center Growing in the 1980s 1 Of Robbery in Vermont 1 As Red Sox Learn Page 2 Page 10 1 Page 1 2 1 Page 13 L 1 Cloudy, Showers Through Saturday Details .on page 2 Coal Standards Vol. XCVIII, No. 200 — Manchester, Conn., Friday, May 25,1979 a A Family NEWSpaper Since 1881 • 20C Single Copy • 15$ Home Delivered WASHINGTON (UPI) - The Environmental Protection Agen cy today announced strict emis sion standards for new coal-fired power plants and said they will cost $35 billion but will clear the Gas Prices air of acid rain after the turn of the century. The standards apply to all new power plants for which' construc tion began after Sept. 18, 1978. The proposal is believed to be Spark Rise one of the most costly ever proposed by the EPA, but ad ministrator Douglas Costle said it is necessary to protect health and environment in light of the ad In Inflation ministration’s plan to triple coal use and production to meet the WASHINGTON (UPI) - Gasoline cent. -

Staging the Urban Soundscape in Fiction Film

Echoes of the city : staging the urban soundscape in fiction film Citation for published version (APA): Aalbers, J. F. W. (2013). Echoes of the city : staging the urban soundscape in fiction film. Maastricht University. https://doi.org/10.26481/dis.20131213ja Document status and date: Published: 01/01/2013 DOI: 10.26481/dis.20131213ja Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. -

28 Affiliated Colleges - Trinity College

AFFILIATED COLLEGES. The establishment of Affiliated Colleges is specially pro vided for in the Act of Incorporation, as will be perceived by a reference to the 8th clause of that measure. The Church of Kngland is the only denomination that has yet availed itself of the right thus accorded. Their founda tion, which bears the name of Trinity College, was affiliated in February Term, 1876. A short account of this College is here appended:— TRINITY COLLEGE. Trinity College stands in a section of the University Re serve, facing the Sydney road. It was built by means of the voluntary contributions of members of the Church of England, supplemented by a loan from Bishop Perry. The first stone was laid on February 10, 1870, and the College was opened for the reception of Students in JulyTerm, 1872, TheBev. G.W. Torrance, M.A., had been appointed Acting Head of the College in February Term, 1872, and held office till the commencement of February Term, 1876. At this time it was determined to establish the College on a more settled basis. Mr. Torrance resigned, and the present Principal was appointed. Until then the College had been little else than a boarding-house, as there was no provision made for the instruction of .Students. Since that time, in addition to the enforcement of discipline and moral and religious supervision, the Students have been able to enjoy the advantage of regular tuition in preparation for the lectures and examinations of the University. The buildings, when completed, will consist of a Chapel, Dining Hall, Library, Provost's Irodge, Lecture Rooms, and sets of Chambers for Students. -

Stevensoniana; an Anecdotal Life and Appreciation of Robert Louis Stevenson, Ed. from the Writings of JM Barrie, SR Crocket

: R. L. S. AND HIS CONTEMPORARIES 225 XII R. L. S. AND HIS CONTEMPORARIES Few authors of note have seen so many and frank judg- ments of their work from the pens of their contemporaries as Stevenson saw. He was a ^persona grata ' with the whole world of letters, and some of his m,ost admiring critics were they of his own craft—poets, novelists, essayists. In the following pages the object in view has been to garner a sheaf of memories and criticisms written—before and after his death—for the most part by eminent contemporaries of the novelist, and interesting, apart from intrinsic worth, by reason of their writers. Mr. Henry James, in his ' Partial Portraits,' devotes a long and brilliant essay to Stevenson. Although written seven years prior to Stevenson's death, and thus before some of the most remarkable productions of his genius had appeared, there is but little in -i^^^ Mr. James's paper which would require modi- fication to-day. Himself the wielder of a literary style more elusive, more tricksy than Stevenson's, it is difficult to take single passages from his paper, the whole galaxy of thought and suggestion being so cleverly meshed about by the dainty frippery of his manner. Mr. James begins by regretting the 'extinction of the pleasant fashion of the literary portrait,' and while deciding that no individual can bring it back, he goes on to say It is sufficient to note, in passing, that if Mr. Stevenson had P 226 STEVENSONIANA presented himself in an age, or in a country, of portraiture, the painters would certainly each have had a turn at him. -

DCP - Verleihangebot

Mitglied der Fédération D FF – Deutsches Filminstitut & Tel.: +49 (0)611 / 97 000 10 www.dff.film Wiesbadener Volksbank Internationale des Archives Filmmuseum e.V. Fax: +49 (0)611 / 97 000 15 E-Mail: wessolow [email protected] IBAN: D E45510900000000891703 du Film (FIAF) Filmarchiv BIC: WIBADE5W XXX Friedrich-Bergius-Stra ß e 5 65203 Wiesbaden 08/ 2019 DCP - Verleihangebot Die angegebenen Preise verstehen sich pro Vorführung (zzgl. 7 % MwSt. und Versandkosten) inkl. Lizenzgebühren Erläuterung viragiert = ganze Szenen des Films sind monochrom eingefärbt koloriert = einzelne Teile des Bildes sind farblich bearbeitet ohne Angabe = schwarz/weiß restauriert = die Kopie ist technisch bearbeitet rekonstruiert = der Film ist inhaltlich der ursprünglichen Fassung weitgehend angeglichen eUT = mit englischen Untertiteln Kurz-Spielfilm = kürzer als 60 Minuten Deutsches Filminstitut - DIF DCP-Verleihangebot 08/2019 Zwischen Stummfilm Titel / Land / Jahr Regie / Darsteller Titel / Format Preis € Tonfilm Sprache DIE ABENTEUER DES PRINZEN Regie: Lotte Reiniger ACHMED Stummfilm deutsch DCP 100,-- D 1923 / 26 viragiert | restauriert (1999) ALRAUNE Regie: Arthur Maria Rabenalt BRD 1952 Tonfilm Darsteller: Hildegard Knef, Karlheinz Böhm deutsch DCP 200,-- Erich von Stroheim, Harry Meyen ALVORADA - AUFBRUCH IN Regie: Hugo Niebeling BRASILIEN DCP (Dokumentarfilm) Tonfilm deutsch 200,-- Bluray BRD 1961/62 FARBFILM AUF DER REEPERBAHN Regie: Wolfgang Liebeneiner NACHTS UM HALB EINS Tonfilm Darsteller: Hans Albers Fita Benkhoff deutsch DCP 200,-- BRD 1954 Heinz Rühmann Gustav Knuth AUS EINEM DEUTSCHEN Regie: Theodor Kotulla LEBEN Tonfilm Darsteller: Götz George Elisabeth Schwarz deutsch DCP 200,-- BRD 1976/1977 Kai Taschner Hans Korte Regie: Ernst Lubitsch DIE AUSTERNPRINZESSIN deutsch Stummfilm Darsteller: Ossi Oswalda Victor Janson DCP 130,-- Deutschland 1919 eUT mögl.