Final Report out of Sight, out of Mind: the Aftermath of Syria’S Sieges Siege Watch Final Report out of Sight, out of Mind: the Aftermath of Syria’S Sieges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral Update of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic

Distr.: General 18 March 2014 Original: English Human Rights Council Twenty-fifth session Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Oral Update of the independent international commission of inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic 1 I. Introduction 1. The harrowing violence in the Syrian Arab Republic has entered its fourth year, with no signs of abating. The lives of over one hundred thousand people have been extinguished. Thousands have been the victims of torture. The indiscriminate and disproportionate shelling and aerial bombardment of civilian-inhabited areas has intensified in the last six months, as has the use of suicide and car bombs. Civilians in besieged areas have been reduced to scavenging. In this conflict’s most recent low, people, including young children, have starved to death. 2. Save for the efforts of humanitarian agencies operating inside Syria and along its borders, the international community has done little but bear witness to the plight of those caught in the maelstrom. Syrians feel abandoned and hopeless. The overwhelming imperative is for the parties, influential states and the international community to work to ensure the protection of civilians. In particular, as set out in Security Council resolution 2139, parties must lift the sieges and allow unimpeded and safe humanitarian access. 3. Compassion does not and should not suffice. A negotiated political solution, which the commission has consistently held to be the only solution to this conflict, must be pursued with renewed vigour both by the parties and by influential states. Among victims, the need for accountability is deeply-rooted in the desire for peace. -

Second Quarterly Report on Besieged Areas in Syria May 2016

Siege Watch Second Quarterly Report on besieged areas in Syria May 2016 Colophon ISBN/EAN:9789492487018 NUR 698 PAX serial number: PAX/2016/06 About PAX PAX works with committed citizens and partners to protect civilians against acts of war, to end armed violence, and to build just peace. PAX operates independently of political interests. www.paxforpeace.nl / P.O. Box 19318 / 3501 DH Utrecht, The Netherlands / [email protected] About TSI The Syria Institute (TSI) is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan think tank based in Washington, DC. TSI was founded in 2015 in response to a recognition that today, almost six years into the Syrian conflict, information and understanding gaps continue to hinder effective policymaking and drive public reaction to the unfolding crisis. Our aim is to address these gaps by empowering decision-makers and advancing the public’s understanding of the situation in Syria by producing timely, high quality, accessible, data-driven research, analysis, and policy options. To learn more visit www.syriainstitute.org or contact TSI at [email protected]. Photo cover: Women and children spell out ‘SOS’ during a protest in Daraya on 9 March 2016, (Source: courtesy of Local Council of Daraya City) Siege Watch Second Quarterly Report on besieged areas in Syria May 2016 Table of Contents 4 PAX & TSI ! Siege Watch Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 8 Key Findings and Recommendations 9 1. Introduction 12 Project Outline 14 Challenges 15 General Developments 16 2. Besieged Community Overview 18 Damascus 18 Homs 30 Deir Ezzor 35 Idlib 38 Aleppo 38 3. Conclusions and Recommendations 40 Annex I – Community List & Population Data 46 Index of Maps & Tables Map 1. -

FSS Wos Response Analysis

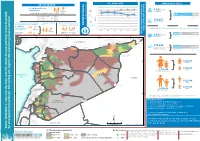

SO1 RESPONSE MARCH 2017 CYCLE Y PEOPLE IN NEED N I 8 B G Food & Livelihood 7.0 7.0 7.0 I 9 7 6.3 6.3 6.3 5.38million Assistance HED OR Food Basket Million C e 6 l Humanitarian Needs Overview (HNO) - 2017 6.16 D SO1 5.8 5.89 5.78 5 N 4 M m 1.16.338m M 5.38 3.35 Target REA September 2015 8.7 Million 5.15 A From within Syria From neighbouring e 4 countries June 2016 9.4 Million WHOLE OF SYRIA ES ES Million peop I nc September 2016 9.0 Million 129,657 3 Cash and Voucher ITI LIFE SUSTAINING AND LIFE SAVING AR ta OVERALL TARGET MARCH 2017 RESPONSE 2 BENEFICIARIES Reached s FOOD ASSISTANCE (SO1) TARGET SO1 Food Basket, Cash & Voucher i Beneficiaries 1 Food Basket, ICI Cash & Voucher - ODAL Additionally, Bread - Flour and Ready to Eat Rations were also Provided ss 7 EF 5.38 0 life sustaining Million M 9 Million OCT NOV DEC JAN FEB MAR N a E nsecure Million Emergency i d B 2 Response (77%) of SO1 Target o 608,654 1.84 M Million Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) - 2017 2.45million From within Syria From neighbouring od 36°0'0"E 38°0'0"E 40°0'0"E 42°0'0"E Bread-Flour fo countries 7 7 o c 1 Cizre- f 1 0 g! i 0 ng 2 Nusaybin-Al i 2 Kiziltepe-Ad l T U R K E Y Qamishli Peshkabour T U R K E Y Darbasiyah n Ayn al g! ! g! h g Arab Ceylanpinar-Ras c b Al Ayn Al Yaroubiya 170,555 r Islahiye Karkamis-Jarabulus g! - Rabiaa tai Akcakale-Tall ! Emergency Response with 116,265 a g! g! g g! 54,290 u Bab As Abiad Ready to Eat Ration From neighbouring M Salama Cobanbey g! From within Syria - countries ssessed g! g! p sus ) a 1 t e Reyhanli - A L --H A S A K E H fe -

Post-Reconciliation Rural Damascus: Are Local Communities Still Represented?

Post-Reconciliation Rural Damascus: Are Local Communities Still Represented? Mazen Ezzi Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) Research Project Report 27 November 2020 2020/16 © European University Institute 2020 Content and individual chapters © Mazen Ezzi 2020 This work has been published by the European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. Requests should be addressed to [email protected]. Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual authors and not those of the European University Institute. Middle East Directions Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Research Project Report RSCAS/Middle East Directions 2020/16 27 November 2020 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ cadmus.eui.eu Funded by the European Union Post-Reconciliation Rural Damascus: Are Local Communities Still Represented? Mazen Ezzi * Mazen Ezzi is a Syrian researcher working on the Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) project within the Middle East Directions Programme hosted by the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the European University Institute in Florence. Ezzi’s work focuses on the war economy in Syria and regime-controlled areas. This research report was first published in Arabic on 19 November 2020. It was translated into English by Alex Rowell. -

Security Council Distr.: General 8 November 2012

United Nations S/2012/550 Security Council Distr.: General 8 November 2012 Original: English Identical letters dated 13 July 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council Upon instructions from my Government, and following my letters dated 16 to 20 and 23 to 25 April, 7, 11, 14 to 16, 18, 21, 24, 29 and 31 May, 1, 4, 6, 7, 11, 19, 20, 25, 27 and 28 June, and 2, 3, 9 and 11 July 2012, I have the honour to attach herewith a detailed list of violations of cessation of violence that were committed by armed groups in Syria on 9 July 2012 (see annex). It would be highly appreciated if the present letter and its annex could be circulated as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Bashar Ja’afari Ambassador Permanent Representative 12-58099 (E) 271112 281112 *1258099* S/2012/550 Annex to the identical letters dated 13 July 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council [Original: Arabic] Monday, 9 July 2012 Rif Dimashq governorate 1. At 2200 hours on it July 2012, an armed terrorist group abducted Chief Warrant Officer Rajab Ballul in Sahnaya and seized a Government vehicle, licence plate No. 734818. 2. At 0330 hours, an armed terrorist group opened fire on the law enforcement checkpoint of Shaykh Ali, wounding two officers. 3. At 0700 hours, an armed terrorist group detonated an explosive device as a law enforcement overnight bus was passing the Artuz Judaydat al-Fadl turn-off on the Damascus-Qunaytirah road, wounding three officers. -

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1 S-JO-100-18-CA-004 Weekly Report 209-212 — October 1–31, 2018 Michael D. Danti, Marina Gabriel, Susan Penacho, Darren Ashby, Kyra Kaercher, Gwendolyn Kristy Table of Contents: Other Key Points 2 Military and Political Context 3 Incident Reports: Syria 5 Heritage Timeline 72 1 This report is based on research conducted by the “Cultural Preservation Initiative: Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq.” Weekly reports reflect reporting from a variety of sources and may contain unverified material. As such, they should be treated as preliminary and subject to change. 1 Other Key Points ● Aleppo Governorate ○ Cleaning efforts have begun at the National Museum of Aleppo in Aleppo, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Heritage Response Report SHI 18-0130 ○ Illegal excavations were reported at Shash Hamdan, a Roman tomb in Manbij, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0124 ○ Illegal excavation continues at the archaeological site of Cyrrhus in Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0090 UPDATE ● Deir ez-Zor Governorate ○ Artillery bombardment damaged al-Sayyidat Aisha Mosque in Hajin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0118 ○ Artillery bombardment damaged al-Sultan Mosque in Hajin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0119 ○ A US-led Coalition airstrike destroyed Ammar bin Yasser Mosque in Albu-Badran Neighborhood, al-Susah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0121 ○ A US-led Coalition airstrike damaged al-Aziz Mosque in al-Susah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. -

HOW to HELP SYRIA RECOVER? Policy Paper 2

HOW TO HELP SYRIA RECOVER? Policy Paper 2 Author: Collective of the “SDGs and Migration“ project This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of Diaconia of the ECCB and can under no cirmustances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union. The document is part of the „SDGs and Migration – Multipliers and Journalists Addressing Decision Makers and Citizens“ project which is realized in the framework of the Development Education and Awareness Raising (DEAR) programme. Graphic design: BOOM s.r.o. Translation: Mánes překlady a tlumočení The following organizations are involved in the “SGDs and Migration” project, managed by Diaconia of ECCB: Global Call to Action Against Poverty (Belgium), Bulgarian Platform for International Development (Bulgaria), Federazione Organismi Cristiani Servizio Internazionale Volontario (Italy), ActionAid Hellas (Greece), Ambrela (Slovakia) and Povod (Slovenia). 1 POLICY PAPER The humanitarian situation in Syria, and its regional and global dimension With the Syrian crisis about to enter its 10th year, the humanitarian situation in Syria and in the neighbouring con- tinues to be critical. Despite the fact that in some areas of Syria the situation has largely stabilized, in Northwest and Northeast Syria there is the potential for a further escalation. There are risks of new displacements and increased humanitarian needs of a population already affected by years of conflict and depletion of resources, as witnessed in recent months as a result of the Operation Peace Spring in the Northeast and the ongoing Gov- ernment of Syria (GoS) and Government of Russia (GoR) offensive in the Northwest. -

Aid in Danger Monthly News Brief – March 2018 Page 1

Aid in Danger Aid agencies Monthly News Brief March 2018 Insecurity affecting the delivery of aid Security Incidents and Access Constraints This monthly digest comprises threats and incidents of Africa violence affecting the delivery Central African Republic of aid. It is prepared by 05 March 2018: In Paoua town, Ouham-Pendé prefecture, and across Insecurity Insight from the wider Central African Republic, fighting among armed groups information available in open continues to stall humanitarian response efforts. Source: Devex sources. 07 March 2018: In Bangassou city, Mbomou prefecture, rumours of All decisions made, on the basis an armed attack in the city forced several unspecified NGOs to of, or with consideration to, withdraw. Source: RJDH such information remains the responsibility of their 07 March 2018: In Bangassou city, Mbomou prefecture, protesters at respective organisations. a women’s march against violence in the region called for the departure of MINUSCA and the Moroccan UN contingent from Editorial team: Bangassou, accusing them of passivity in the face of threats and Christina Wille, Larissa Fast and harassment. Source: RJDH Laurence Gerhardt Insecurity Insight 09 or 11 March 2018: In Bangassou city, Mbomou prefecture, armed men suspected to be from the Anti-balaka movement invaded the Andrew Eckert base of the Dutch NGO Cordaid, looting pharmaceuticals, work tools, European Interagency Security motorcycles and seats. Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Forum (EISF) Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) personnel intervened, leading to a firefight between MINUSCA and the armed Research team: men. The perpetrators subsequently vandalised the local Médecins James Naudi Sans Frontières (MSF) office. Cars, motorbikes and solar panels Insecurity Insight belonging to several NGOs in the area were also stolen. -

UNRWA-Weekly-Syria-Crisis-Report

UNRWA Weekly Syria Crisis Report, 15 July 2013 REGIONAL OVERVIEW Conflict is increasingly encroaching on UNRWA camps with shelling and clashes continuing to take place near to and within a number of camps. A reported 8 Palestine Refugees (PR) were killed in Syria this week as a result including 1 UNRWA staff member, highlighting their unique vulnerability, with refugee camps often theatres of war. At least 44,000 PR homes have been damaged by conflict and over 50% of all registered PR are now displaced, either within Syria or to neighbouring countries. Approximately 235,000 refugees are displaced in Syria with over 200,000 in Damascus, around 6600 in Aleppo, 4500 in Latakia, 3050 in Hama, 6400 in Homs and 13,100 in Dera’a. 71,000 PR from Syria (PRS) have approached UNRWA for assistance in Lebanon and 8057 (+120 from last week) in Jordan. UNRWA tracks reports of PRS in Egypt, Turkey, Gaza and UNHCR reports up to 1000 fled to Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia. 1. SYRIA Displacement UNRWA is sheltering over 8317 Syrians (+157 from last week) in 19 Agency facilities with a near identical increase with the previous week. Of this 6986 (84%, +132 from last week and nearly triple the increase of the previous week) are PR (see table 1). This follows a fairly constant trend since April ranging from 8005 to a high of 8400 in May. The number of IDPs in UNRWA facilities has not varied greatly since the beginning of the year with the lowest figure 7571 recorded in early January. A further 4294 PR (+75 from last week whereas the week before was ‐3) are being sheltered in 10 non‐ UNRWA facilities in Aleppo, Latakia and Damascus. -

Into the Tunnels

REPORT ARAB POLITICS BEYOND THE UPRISINGS Into the Tunnels The Rise and Fall of Syria’s Rebel Enclave in the Eastern Ghouta DECEMBER 21, 2016 — ARON LUND PAGE 1 In the sixth year of its civil war, Syria is a shattered nation, broken into political, religious, and ethnic fragments. Most of the population remains under the control of President Bashar al-Assad, whose Russian- and Iranian-backed Baʻath Party government controls the major cities and the lion’s share of the country’s densely populated coastal and central-western areas. Since the Russian military intervention that began in September 2015, Assad’s Syrian Arab Army and its Shia Islamist allies have seized ground from Sunni Arab rebel factions, many of which receive support from Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Turkey, or the United States. The government now appears to be consolidating its hold on key areas. Media attention has focused on the siege of rebel-held Eastern Aleppo, which began in summer 2016, and its reconquest by government forces in December 2016.1 The rebel enclave began to crumble in November 2016. Losing its stronghold in Aleppo would be a major strategic and symbolic defeat for the insurgency, and some supporters of the uprising may conclude that they have been defeated, though violence is unlikely to subside. However, the Syrian government has also made major strides in another besieged enclave, closer to the capital. This area, known as the Eastern Ghouta, is larger than Eastern Aleppo both in terms of area and population—it may have around 450,000 inhabitants2—but it has gained very little media interest. -

Forgotten Lives Life Under Regime Rule in Former Opposition-Held East Ghouta

FORGOTTEN LIVES LIFE UNDER REGIME RULE IN FORMER OPPOSITION-HELD EAST GHOUTA A COLLABORATION BETWEEN THE MIDDLE EAST INSTITUTE AND ETANA SYRIA MAY 2019 POLICY PAPER 2019-10 CONTENTS * SUMMARY * KEY POINTS AND STATISTICS * 1 INTRODUCTION * 2 MAIN AREAS OF CONTROL * 3 MAP OF EAST GHOUTA * 6 MOVEMENT OF CIVILIANS * 8 DETENTION CENTERS * 9 PROPERTY AND REAL ESTATE UPHEAVAL * 11 CONCLUSION Cover Photo: Syrian boy cycles down a destroyed street in Douma on the outskirts of Damascus on April 16, 2018. (LOUAI BESHARA/AFP/Getty Images) © The Middle East Institute Photo 2: Pro-government soldiers stand outside the Wafideen checkpoint on the outskirts of Damascus on April 3, 2018. (Photo by LOUAI BESHARA/ The Middle East Institute AFP) 1319 18th Street NW Washington, D.C. 20036 SUMMARY A “black hole” of information due to widespread fear among residents, East Ghouta is a dark example of the reimposition of the Assad regime’s authoritarian rule over a community once controlled by the opposition. A vast network of checkpoints manned by intelligence forces carry out regular arrests and forced conscriptions for military service. Russian-established “shelters” house thousands and act as detention camps, where the intelligence services can easily question and investigate people, holding them for periods of 15 days to months while performing interrogations using torture. The presence of Iranian-backed militias around East Ghouta, to the east of Damascus, underscores the extent of Iran’s entrenched strategic control over key military points around the capital. As collective punishment for years of opposition control, East Ghouta is subjected to the harshest conditions of any of the territories that were retaken by the regime in 2018, yet it now attracts little attention from the international community. -

Reconstruct- Ing Syria: Risks and Side Effects Strategies, Actors and Interests

ZUSAMMENFASSUNG ADOPT A REVOLUTION RECONSTRUCT- ING SYRIA: RISKS AND SIDE EFFECTS Strategies, actors and interests 1 2 Cover photo: Jan-Niklas Kniewel RECONSTRUCTING SYRIA: RISKS AND SIDE EFFECTS ADOPT A REVOLUTION CONTENT Summary 04 Introduction 06 Dr. Joseph Daher Reconstructing Syria: How the al-Assad regime is 09 capitalizing on destruction Jihad Yazigi Reconstruction or Plunder? How Russia and Iran are 20 dividing Syrian Resources Dr. Salam Said Reconstruction as a foreign policy tool 30 Alhakam Shaar Reconstruction, but for whom? Embracing the role of Aleppo’s 34 displaced Dispossessed and deprived: 39 Three case studies of Syrians affected by the Syrian land and property rights 03 SUMMARY RECONSTRUCTING SYRIA: RISKS AND SIDE EFFECTS SUMMARY 1 The reconstruction plans of the al-Assad regime largely ignore the needs of internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees. The regime’s reconstruction strategy does not address the most pressing needs of over 10 million Syrian IDPs and refugees. Instead it caters mostly to the economic interests of the regime itself and its allies. 2 Current Syrian legislation obstructs the return of IDPs and refugees, and legalizes the deprivation of rights of residents of informal settlements. A series of tailor-made laws have made it legal to deprive inhabitants of informal settlements of their rights. This includes the restriction of housing, land and property rights through Decree 66, Law No. 10, the restriction of basic rights under the counterterrorism law, and the legal bases for public-private co-investments. These laws also serve the interests of regime cronies and regime-loyal forces. The process of demographic engineering in former opposition-held territories, which has already begun, driven by campaigns of forced displacement and the evictions of original residents, is being cemented by these laws.