Assessment for the Western Pond Turtle Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life History Account for Western Pond Turtle

California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Interagency Wildlife Task Group WESTERN POND TURTLE Actinemys marmorata Family: EMYDIDAE Order: TESTUDINES Class: REPTILIA R004 Written by: S. Morey Reviewed by: T. Papenfuss Edited by: R. Duke Updated by: CWHR Program Staff, March 2000 DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND SEASONALITY The western pond turtle is uncommon to common in suitable aquatic habitat throughout California, west of the Sierra-Cascade crest and absent from desert regions, except in the Mojave Desert along the Mojave River and its tributaries. Elevation range extends from near sea level to 1430 m (4690 ft) (Jennings and Hayes 1994). Associated with permanent or nearly permanent water in a wide variety of habitat types. SPECIFIC HABITAT REQUIREMENTS Feeding: This species is considered omnivorous. Aquatic plant material, including pond lilies, beetles and a variety of aquatic invertebrates as well as fishes, frogs, and even carrion have been reported among their food (Stebbins 1972, Nussbaum et al. 1983). Cover: Pond turtles require basking sites such as partially submerged logs, rocks, mats of floating vegetation, or open mud banks. Turtles slip from basking sites to underwater retreats at the approach of humans or potential predators. Hibernation in colder areas is passed underwater in bottom mud. Reproduction: Storer (1930) suggested that two distinct habitats may be used for oviposition. Along large slow-moving streams, eggs are deposited in nests constructed in sandy banks. Along foothill streams, females may climb hillsides, sometimes moving considerable distances to find a suitable nest site. Nussbaum et al. (1983) reports a nest in a clover field 100 m (325 ft) from water. -

Competing Generic Concepts for Blanding's, Pacific and European

Zootaxa 2791: 41–53 (2011) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2011 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Competing generic concepts for Blanding’s, Pacific and European pond turtles (Emydoidea, Actinemys and Emys)—Which is best? UWE FRITZ1,3, CHRISTIAN SCHMIDT1 & CARL H. ERNST2 1Museum of Zoology, Senckenberg Dresden, A. B. Meyer Building, D-01109 Dresden, Germany 2Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, MRC 162, Smithsonian Institution, P.O. Box 37012, Washington, D.C. 20013-7012, USA 3Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract We review competing taxonomic classifications and hypotheses for the phylogeny of emydine turtles. The formerly rec- ognized genus Clemmys sensu lato clearly is paraphyletic. Two of its former species, now Glyptemys insculpta and G. muhlenbergii, constitute a well-supported basal clade within the Emydinae. However, the phylogenetic position of the oth- er two species traditionally placed in Clemmys remains controversial. Mitochondrial data suggest a clade embracing Actinemys (formerly Clemmys) marmorata, Emydoidea and Emys and as its sister either another clade (Clemmys guttata + Terrapene) or Terrapene alone. In contrast, nuclear genomic data yield conflicting results, depending on which genes are used. Either Clemmys guttata is revealed as sister to ((Emydoidea + Emys) + Actinemys) + Terrapene or Clemmys gut- tata is sister to Actinemys marmorata and these two species together are the sister group of (Emydoidea + Emys); Terra- pene appears then as sister to (Actinemys marmorata + Clemmys guttata) + (Emydoidea + Emys). The contradictory branching patterns depending from the selected loci are suggestive of lineage sorting problems. Ignoring the unclear phy- logenetic position of Actinemys marmorata, one recently proposed classification scheme placed Actinemys marmorata, Emydoidea blandingii, Emys orbicularis, and Emys trinacris in one genus (Emys), while another classification scheme treats Actinemys, Emydoidea, and Emys as distinct genera. -

****************************************It******************* Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 332 166 CS 010 588 AUTHOR Costa, Arthur L., E. TITLE Developing Minds: A Resource Book for Teaching Thinking. Revised Edition, Volume 1. INSTITUTION Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, Alexandria, Va. REPORT NO ISBN-87120-180-1 PUB DATE 91 NOTE 411p.; For volume 2, see CS 010 589. For previous edition, see ED 262 968. AVAILABLE FROMAssociation for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 1250 North Pitt St., Alexandria, VA 22314 (Stock No. 611-91026, $24.95). PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Cognitive Processes; *Comprehension; Concept Formation; Creative Thinking; *Critical Thinking; Curriculum Design; Curriculum Development; Curriculum Evaluation; Decision Making; Developmental Stages; Elementary Secondary Education; *Problem Solving; *Program Descriptions; Teaching Methods; *Thinking Skills ABSTRACT This eight-part book contains 69 articles which address topics related to helping students become effective thinkers. The articles are organized under these categories:(1) the need to teach students to think; (2) creating school conditions for thinking; (3) what is thinking? deciding on definitions; (4) a curriculum for thinking; (5) thinking pervades the curriculum; (6) teaching for thinking; (7) teaching strategies; and (8) assessing growth in thinking abilities. The book lists other resources for teaching thinking (in nine appendixes) which include a glossary of cognitive terminology, observation forms, checklists, questionnaires, evaluation instruments, suggestions for getting started, and questions for system planners. (PRA) ***************************************************It******************* Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** A RESOURCE BOOK FOR TEACHING THINKING Revised Edition, Volume 1 Edited by Arthur L. -

Western Painted Turtle (Chrysemys Picta)

Western Painted Turtle (Chrysemys picta) Class: Reptilia Order: Testudines Family: Emydidae Characteristics: The most widespread native turtle of North America. It lives in slow-moving fresh waters, from southern Canada to Louisiana and northern Mexico, and from the Atlantic to the Pacific. The adult painted turtle female is 10–25 cm (4–10 in) long; the male is smaller. The turtle's top shell is dark and smooth, without a ridge. Its skin is olive to black with red, orange, or yellow stripes on its extremities. The subspecies can be distinguished by their shells: the eastern has straight-aligned top shell segments; the midland has a large gray mark on the bottom shell; the southern has a red line on the top shell; the western has a red pattern on the bottom shell (Washington Nature Mapping Program). Behavior: Although they are frequently consumed as eggs or hatchlings by rodents, canines, and snakes, the adult turtles' hard shells protect them from most predators. Reliant on warmth from its surroundings, the painted turtle is active only during the day when it basks for hours on logs or rocks. During winter, the turtle hibernates, usually in the mud at the bottom of water bodies. Reproduction: The turtles mate in spring and autumn. Females dig nests on land and lay eggs between late spring and mid- summer. Hatched turtles grow until sexual maturity: 2–9 years for males, 6–16 for females. Diet: Wild: aquatic vegetation, algae, and small water creatures including insects, crustaceans, and fish Zoo: Algae, duck food Conservation: While habitat loss and road killings have reduced the turtle's population, its ability to live in human-disturbed settings has helped it remain the most abundant turtle in North America. -

Afraid of Bear to Zuni: Surnames in English of Native American Origin Found Within

RAYNOR MEMORIAL LIBRARIES Indian origin names, were eventually shortened to one-word names, making a few indistinguishable from names of non-Indian origin. Name Categories: Personal and family names of Indian origin contrast markedly with names of non-Indian Afraid of Bear to Zuni: Surnames in origin. English of Native American Origin 1. Personal and family names from found within Marquette University Christian saints (e.g. Juan, Johnson): Archival Collections natives- rare; non-natives- common 2. Family names from jobs (e.g. Oftentimes names of Native Miller): natives- rare; non-natives- American origin are based on objects common with descriptive adjectives. The 3. Family names from places (e.g. following list, which is not Rivera): natives- rare; non-native- comprehensive, comprises common approximately 1,000 name variations in 4. Personal and family names from English found within the Marquette achievements, attributes, or incidents University archival collections. The relating to the person or an ancestor names originate from over 50 tribes (e.g. Shot with two arrows): natives- based in 15 states and Canada. Tribal yes; non-natives- yes affiliations and place of residence are 5. Personal and family names from noted. their clan or totem (e.g. White bear): natives- yes; non-natives- no History: In ancient times it was 6. Personal or family names from customary for children to be named at dreams and visions of the person or birth with a name relating to an animal an ancestor (e.g. Black elk): natives- or physical phenominon. Later males in yes; non-natives- no particular received names noting personal achievements, special Tribes/ Ethnic Groups: Names encounters, inspirations from dreams, or are expressed according to the following physical handicaps. -

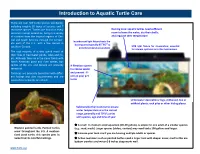

Introduction to Aquatic Turtle Care

Mississippi Map Turtle Introduction to Aquatic Turtle Care There are over 300 turtle species worldwide, including roughly 60 types of tortoise and 7 sea turtle species. Turtles are found on every Basking area: aquatic turtles need sufficient continent except Antarctica, living in a variety room to leave the water, dry their shells, of climates from the tropical regions of Cen- and regulate their temperature. tral and South America through the temper- Incandescent light fixture heats the ate parts of the U.S., with a few species in o- o) basking area (typically 85 95 to UVB light fixture for illumination; essential southern Canada. provide temperature gradient for vitamin synthesis in turtles held indoors The vast majority of turtles spend much of their lives in freshwater ponds, lakes and riv- ers. Although they are in the same family with North American pond and river turtles, box turtles of the U.S. and Mexico are primarily A filtration system terrestrial. to remove waste Tortoises are primarily terrestrial with differ- and prevent ill- ent habitat and diet requirements and are ness in your pet covered in a separate care sheet. turtle Underwater decorations: logs, driftwood, live or artificial plants, rock piles or other hiding places. Submersible thermometer to ensure water temperature is in the correct range, generally mid 70osF; varies with species, age and time of year A small to medium-sized aquarium (20-29 gallons) is ample for one adult of a smaller species Western painted turtle. Painted turtles (e.g., mud, musk). Larger species (sliders, cooters) may need tanks 100 gallons and larger. -

Year of the Turtle News No

Year of the Turtle News No. 1 January 2011 Basking in the Wonder of Turtles www.YearoftheTurtle.org Welcome to 2011, the Wood Turtle, J.D. Kleopfer Bog Turtle, J.D. Willson Year of the Turtle! Turtle conservation groups in partnership with PARC have designated 2011 as the Year of the Turtle. The Chinese calendar declares 2011 as the Year of the Rabbit, and we are all familiar with the story of the “Tortoise and the Hare”. Today, there Raising Awareness for Turtle State of the Turtle Conservation is in fact a race in progress—a race to extinction, and turtles, unfortunately, Trouble for Turtles Our Natural Heritage of Turtles are emerging in the lead, ahead The fossil record shows us that While turtles (which include of birds, mammals, and even turtles, as we know them today, have tortoises) occur in fresh water, salt amphibians. The majority of turtle been on our planet since the Triassic water, and on land, their shells make threats are human-caused, which also Period, over 220 million years ago. them some of the most distinctive means that we can work together to Although they have persisted through animals on Earth. Turtles are so address turtle conservation issues many tumultuous periods of Earth’s unique that some scientists argue that and to help ensure the continued history, from glaciations to continental they should be in their own Class of survival of these important animals. shifts, they are now at the top of the vertebrates, Chelonia, separate from Throughout the year we will be raising list of species disappearing from the reptiles (such as lizards and snakes) awareness of the issues surrounding planet: 47.6% of turtle species are and other four-legged creatures. -

AN INTRODUCTION to Texas Turtles

TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE AN INTRODUCTION TO Texas Turtles Mark Klym An Introduction to Texas Turtles Turtle, tortoise or terrapin? Many people get confused by these terms, often using them interchangeably. Texas has a single species of tortoise, the Texas tortoise (Gopherus berlanderi) and a single species of terrapin, the diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin). All of the remaining 28 species of the order Testudines found in Texas are called “turtles,” although some like the box turtles (Terrapene spp.) are highly terrestrial others are found only in marine (saltwater) settings. In some countries such as Great Britain or Australia, these terms are very specific and relate to the habit or habitat of the animal; in North America they are denoted using these definitions. Turtle: an aquatic or semi-aquatic animal with webbed feet. Tortoise: a terrestrial animal with clubbed feet, domed shell and generally inhabiting warmer regions. Whatever we call them, these animals are a unique tie to a period of earth’s history all but lost in the living world. Turtles are some of the oldest reptilian species on the earth, virtually unchanged in 200 million years or more! These slow-moving, tooth less, egg-laying creatures date back to the dinosaurs and still retain traits they used An Introduction to Texas Turtles | 1 to survive then. Although many turtles spend most of their lives in water, they are air-breathing animals and must come to the surface to breathe. If they spend all this time in water, why do we see them on logs, rocks and the shoreline so often? Unlike birds and mammals, turtles are ectothermic, or cold- blooded, meaning they rely on the temperature around them to regulate their body temperature. -

The Western Pond Turtle: Habitat and History

THE WESTERN POND TURTLE: HABITAT AND HISTORY FINAL REPORT Prepared by: Dan C. Holland, PhD Wildlife Diversity Program Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Portland, OR Prepared for: U. S. Department ofEnergy Bonneville Power Administration Environment, Fish and Wildlife P. O. Box 3621 Portland, OR 97208-3 62 1 Project Number 92-068 Contract Number DE-BI79-92BP62 137 August 1994 TABLE OF CONTENTSf1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Pat,:e Chapter 1 A Brief Overview of the Evolution of the Willamette-Puget Sound Hydrographic Basin Introduction .1-3 The Biotic Landscape ofthe Willamette Valley in the Holocene .1-7 The Historical Appearance of the Willamette Valley ca: 18 10- 1860 .1-15 The Influence ofHumans on the Biotic Landscape ofthe Willamette Valley .1-19 Changes in the Biotic Landscape: 1840's-1940' .1-22 Literature Cited .1-31 Chapter 2 A Synopsis of the Natural History of the Western Pond Turtle Taxonomy 2-3 Description , 2-3 Range 2-4 Distribution-Oregon 2-4 Behavior 2-5 Diet 2-5 Home Range 2-6 Activity '" 2-6 Habitat Requirements--Aquatic Habitats .2-7 Habitat Requirements--Terrestrial Habitats .2-8 Overland Movements 2-9 Reproduction 2-9 Growth and Survivorship .2-11 Predation and Mortality 2-11 Disease 2-13 Parasites 2-14 Drought. .2-14 Literature Cited .2-15 Chapter 3 Methods 3-1 Chapter 4 Status of the Western Pond Turtle in the Willamette Drainage Historical Background 4-3 Recent Studies 4-4 Survey Effort Goals 4-4 Overall Results 4-5 Other Studies 4-5 Locality Data 4-6 Population Structure 4-6 Population Size 4-8 TABLE OF CONTENTS/2 -

Ecology and Conservation Biology of the North American Wood Turtle (Glyptemys

Ecology and Conservation Biology of the North American Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) in the Central Appalachians A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Steven P. Krichbaum May 2018 © 2018 Steven P. Krichbaum. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Ecology and Conservation Biology of the North American Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) in the Central Appalachians by STEVEN P. KRICHBAUM has been approved for the Department of Biological Sciences and the College of Arts and Sciences by Willem Roosenburg Professor of Biological Sciences Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 Abstract KRICHBAUM, STEVEN P., Ph.D., May 2018, Biological Sciences Ecology and Conservation Biology of the North American Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) in the Central Appalachians Director of Dissertation: Willem Roosenburg My study presents information on summer use of terrestrial habitat by IUCN “endangered” North American Wood Turtles (Glyptemys insculpta), sampled over four years at two forested montane sites on the southern periphery of the species’ range in the central Appalachians of Virginia (VA) and West Virginia (WV) USA. The two sites differ in topography, stream size, elevation, and forest composition and structure. I obtained location points for individual turtles during the summer, the period of their most extensive terrestrial roaming. Structural, compositional, and topographical habitat features were measured, counted, or characterized on the ground (e.g., number of canopy trees and identification of herbaceous taxa present) at Wood Turtle locations as well as at paired random points located 23-300m away from each particular turtle location. -

EMYDIDAE P Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles

REPTILIA: TESTUDINES: EMYDIDAE P Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Pseudemysj7oridana: Baur, 1893:223 (part). Pseudemys texana: Brimley, 1907:77 (part). Seidel, M.E. and M.J. Dreslik. 1996. Pseudemys concinna. Chrysemysfloridana: Di tmars, 1907:37 (part). Chrysemys texana: Hurter and Strecker, 1909:21 (part). Pseudemys concinna (LeConte) Pseudemys vioscana Brimley, 1928:66. Type-locality, "Lake River Cooter Des Allemands [St. John the Baptist Parrish], La." Holo- type, National Museum of Natural History (USNM) 79632, Testudo concinna Le Conte, 1830: 106. Type-locality, "... rivers dry adult male collected April 1927 by Percy Viosca Jr. of Georgia and Carolina, where the beds are rocky," not (examined by authors). "below Augusta on the Savannah, or Columbia on the Pseudemys elonae Brimley, 1928:67. Type-locality, "... pond Congaree," restricted to "vicinity of Columbia, South Caro- in Guilford County, North Carolina, not far from Elon lina" by Schmidt (1953: 101). Holotype, undesignated, see College, in the Cape Fear drainage ..." Holotype, USNM Comment. 79631, dry adult male collected October 1927 by D.W. Tesrudofloridana Le Conte, 1830: 100 (part). Type-locality, "... Rumbold and F.J. Hall (examined by authors). St. John's river of East Florida ..." Holotype, undesignated, see Comment. Emys (Tesrudo) concinna: Bonaparte, 1831 :355. Terrapene concinna: Bonaparte, 183 1 :370. Emys annulifera Gray, 183 1:32. Qpe-locality, not given, des- ignated as "Columbia [Richland County], South Carolina" by Schmidt (1953: 101). Holotype, undesignated, but Boulenger (1889:84) listed the probable type as a young preserved specimen in the British Museum of Natural His- tory (BMNH) from "North America." Clemmys concinna: Fitzinger, 1835: 124. -

Surveys for Western Pond Turtle Actinemys Marmorata on The

Surveys for Western pond turtle Actinemys marmorata On the Siuslaw National Forest Cynthia G. Burns, Wildlife Biologist U. S. Forest Service Siuslaw National Forest October 29, 2010 SUMMARY Surveys were contracted to establish presence of the western pond turtle (Actinemys marmorata) on lands within or adjacent to the Siuslaw National Forest’s (SNF) Hebo and Central Coast/ODNRA (Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area) Ranger Districts during the summer of 2010. Portions of 5 rivers and 1 lake were surveyed on or near the Central Coast/Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area (ODNRA) Ranger District and 3 lakes were surveyed on the Hebo District. Surveys were conducted by kayak and at fixed points. Two Red-eared Sliders Trachemys scripta elegans were confirmed during contracted surveys. No western pond turtles were found. Habitat and invasive species data were also collected as part of the survey effort. INTRODUCTION The western pond turtle occurs along the Pacific states from Baja California to Puget Sound of Washington. Western pond turtles are listed as endangered in Washington, sensitive critical in Oregon and are a species of concern in Region 6 of the Forest Service (WA & OR). It was proposed for Federal listing in 1991 but was precluded due to lack of supporting evidence on its population trends. In 2010 the Siuslaw National Forest continued surveys of lands within or adjacent to its boundaries in an effort to determine where individuals or populations may still exist. In Oregon, the western pond turtle occurs primarily within the drainages of the Willamette, Umpqua, Rogue and Klamath Rivers but has also been documented in lowland aquatic habitats throughout western Oregon (Rosenberg, 2009).