Relative Abuse Liability of Hypnotic Drugs: a Conceptual Framework and Algorithm for Differentiating Among Compounds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics

Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics Molecular Determinants of Ligand Selectivity for the Human Multidrug And Toxin Extrusion Proteins, MATE1 and MATE-2K Bethzaida Astorga, Sean Ekins, Mark Morales and Stephen H Wright Department of Physiology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85724, USA (B.A., M.M., and S.H.W.) Collaborations in Chemistry, 5616 Hilltop Needmore Road, Fuquay-Varina NC 27526, USA (S.E.) Supplemental Table 1. Compounds selected by the common features pharmacophore after searching a database of 2690 FDA approved compounds (www.collaborativedrug.com). FitValue Common Name Indication 3.93897 PYRIMETHAMINE Antimalarial 3.3167 naloxone Antidote Naloxone Hydrochloride 3.27622 DEXMEDETOMIDINE Anxiolytic 3.2407 Chlordantoin Antifungal 3.1776 NALORPHINE Antidote Nalorphine Hydrochloride 3.15108 Perfosfamide Antineoplastic 3.11759 Cinchonidine Sulfate Antimalarial Cinchonidine 3.10352 Cinchonine Sulfate Antimalarial Cinchonine 3.07469 METHOHEXITAL Anesthetic 3.06799 PROGUANIL Antimalarial PROGUANIL HYDROCHLORIDE 100MG 3.05018 TOPIRAMATE Anticonvulsant 3.04366 MIDODRINE Antihypotensive Midodrine Hydrochloride 2.98558 Chlorbetamide Antiamebic 2.98463 TRIMETHOPRIM Antibiotic Antibacterial 2.98457 ZILEUTON Antiinflammatory 2.94205 AMINOMETRADINE Diuretic 2.89284 SCOPOLAMINE Antispasmodic ScopolamineHydrobromide 2.88791 ARTICAINE Anesthetic 2.84534 RITODRINE Tocolytic 2.82357 MITOBRONITOL Antineoplastic Mitolactol 2.81033 LORAZEPAM Anxiolytic 2.74943 ETHOHEXADIOL Insecticide 2.64902 METHOXAMINE Antihypotensive Methoxamine -

Date Rape and Steroid Panels, Updated Feb 1 2010

DRUG-FACILITATED SEXUAL ASSAULT (aka “DATE RAPE”) AND STEROID PANELS (Effective January 26, 2010) Basic Date Rape Panel Comprehensive Date Rape Panel • GHB (Hair Only) • Ketamine • GHB • Benzodiazepines, including Rohypnol • Benzodiazepines Alprazolam Clonazepam Alprazolam Clonazepam Diazepam Flunitrazepam (Rohypnol) Diazepam Flunitrazepam Lorazepam Oxazepam Lorazepam Oxazepam Temazepam Nitrazepam Temazepam Nitrazepam • Opioids Codeine Hydrocodone Comprehensive Date Rape Panel Meperidine Tramadol (Urine Only) Methadone Fentanyl • GHB • Sedatives/Hypnotics Ketamine Methaqualone • Barbiturates Zolpidem Zopiclone Amobarbital Butalbital Pentobarbital Phenobarbital • Over-The-Counter Drugs Secobarbital Diphenhydramine Dextromethorphan Doxylamine Chlorpheniramine • Benzodiazepines Brompheniramine Promethazine Alprazolam Clonazepam Pheniramine Diazepam Flunitrazepam Lorazepam Oxazepam • Muscle Relaxants Temazepam Nitrazepam Carisoprodol Meprobamate • Opioids Cyclobenzaprine Methocarbamol Codeine Morphine • Hallucinogens (PCP) Hydrocodone Hydromorphone Oxycodone Oxymorphone Meperidine Tramadol ANABOLIC STEROID PANEL Methadone Fentanyl (Urine or Blood) Propoxyphene Buprenorphine Androstenedione Boldenone • Sedatives/Hypnotics Fluoxymesterolone Mesterolone Ketamine Methaqualone 17-a-Methyltestosterone Methenolone Zolpidem Zopiclone Methandrostenolone Nandrolone • Over-The-Counter Drugs Norethandrolone Oxandrolone Diphenhydramine Dextromethorphan Stanozolol Trenbolone Doxylamine Chlorpheniramine Brompheniramine Promethazine Pheniramine For additional steroids, • Muscle Relaxants call for details and pricing Carisoprodol Meprobamate EXPERTOX, INC. Cyclobenzaprine Methocarbamol Blood should only be 1803 CENTER STREET, SUITE A submitted for date rape • Hallucinogens DEER PARK, TX 77536 PCP MDMA panels if within five (5) hours of 281.476.4600 MDA MDEA ingestion. FAX 281.930.8856 Cannabinoids (Carboxy-THC) • WWW.EXPERTOX.COM Turaround Time: Ten (10) Urine must be collected within five (5) days business days from specimen of drug exposure receipt at the lab . -

Paper Clip—High Risk Medications

You belong. PAPER CLIP—HIGH RISK MEDICATIONS Description: Some medications may be risky for people over 65 years of age and there may be safer drug choices to treat some conditions. It is recommended that medications are reviewed regularly with your providers/prescriber to ensure patient safety. Condition Treated Current Medication(s)-High Risk Safer Alternatives to Consider Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs), Nitrofurantoin Bactrim (sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim) or recurrent UTIs, or Prophylaxis (Macrobid, or Macrodantin) Trimpex/Proloprim/Primsol (trimethoprim) Allergies Hydroxyzine (Vistaril, Atarax) Xyzal (Levocetirizine) Anxiety Hydroxyzine (Vistaril, Atarax) Buspar (Buspirone), Paxil (Paroxetine), Effexor (Venlafaxine) Parkinson’s Hydroxyzine (Vistaril, Atarax) Symmetrel (Amantadine), Sinemet (Carbidopa/levodopa), Selegiline (Eldepryl) Motion Sickness Hydroxyzine (Vistaril, Atarax) Antivert (Meclizine) Nausea & Vomiting Hydroxyzine (Vistaril, Atarax) Zofran (Ondansetron) Insomnia Hydroxyzine (Vistaril, Atarax) Ramelteon (Rozerem), Doxepin (Silenor) Chronic Insomnia Eszopiclone (Lunesta) Ramelteon (Rozerem), Doxepin (Silenor) Chronic Insomnia Zolpidem (Ambien) Ramelteon (Rozerem), Doxepin (Silenor) Chronic Insomnia Zaleplon (Sonata) Ramelteon (Rozerem), Doxepin (Silenor) Muscle Relaxants Cyclobenazprine (Flexeril, Amrix) NSAIDs (Ibuprofen, naproxen) or Hydrocodone Codeine Tramadol (Ultram) Baclofen (Lioresal) Tizanidine (Zanaflex) Migraine Prophylaxis Elavil (Amitriptyline) Propranolol (Inderal), Timolol (Blocadren), Topiramate (Topamax), -

National Clearinghouse for Drug Abuse Information Selected Reference Series, Series 1, No

DOCUMENT RESOHE ED 090 455 CG 008 832 TITLE National Clearinghouse For Drug Abuse Information Selected Reference Series, Series 1, No. 1. INSTITUTION National Inst. of Mental Health (DHEW), Rockville, Hd. National Clearinghouse for Drug Abuse Information.; Student Association for the Study of Hallucinogens, Biloit, His. PDB DATE Nov 73 NOTE 13p. AVAILABLE FROM National Clearinghouse for Drug Abuse Information, p. 0. Box 1908, Rockville, Maryland 20850 EDRS PRICE MF-10.75 HC-S1.50 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS ^Bibliographies; *Drug Abuse; *Drug Education; *Drug Therapy; Government Publications; ^Narcotics ABSTRACT One of a series of bibliographies published by the National Clearinghouse for Drug Abuse Information, this reference focuses on the drug, methagualone. Literature is selected for inclusion on the basis of its currency, significance in the field, and its availability to the public. Materials are directed toward researchers, educators, lawyers, physicians, and members of the public with more than a general need for information. Citations are not annotated. (Author/CJ) SERIES 7, No.l NOVEMBER 1973 Each bibliography of the National Clearinghouse for Drug Abuse 3- Information Selected Reference Series is a representative listing of citations on subjects of topical interest. The selection of o literature is based on its currency, its significance in the field, and its availability in local bookstores or research libraries. The scope of the material is directed toward students writing research papers, special interest groups, such as educators, lawyers and phy sicians, and the general public requiring more resources than public information materials can provide. Each reference series is meant to present an overview of the existing literature, but is not meant to be comprehensive or definitive in scope. -

Chemistry Information Sheet Methaqualone © 2014 Beckman Coulter, Inc

SYNCHRON System(s) METQ Chemistry Information Sheet Methaqualone © 2014 Beckman Coulter, Inc. All rights reserved. 475021 For In Vitro Diagnostic Use Rx Only ANNUAL REVIEW Reviewed by Date Reviewed by Date PRINCIPLE INTENDED USE METQ reagent, in conjunction with UniCel® DxC 600/800 System(s) and SYNCHRON® Systems Drugs of Abuse Testing (DAT) Urine Calibrators, is intended for the qualitative determination of methaqualone in human urine at a cutoff value of 300 ng/mL. The METQ assay provides a rapid screening procedure for determining the presence of methaqualone (METQ) and its metabolites in urine. This test provides only a preliminary analytical result; a positive result by this assay should be conrmed by another generally accepted non-immunological method such as thin layer chromatography (TLC), gas chromatography (GC), or gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS). GC/MS is the preferred conrmatory method.1,2 Clinical consideration and professional judgement should be applied to any drug of abuse test result, particularly when preliminary positive results are used. CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE Measurements of methaqualone are used as an aid in the diagnosis and treatment of methaqualone use or overdose. METHODOLOGY The Methaqualone assay utilizes a homogenous enzyme immunoassay method.3 The METQ reagent is comprised of specic antibodies which can detect methaqualone and its metabolites in urine. A drug-labeled glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) conjugate competes with any free drug from the urine sample for a xed amount of antibody binding sites. In the absence of free drug from the sample, the drug-labeled G6PDH conjugate is bound by the specic antibody and the enzyme activity is inhibited. -

Injecting Drug Users Etc.)

Economic and Social Council E/NR/2015/3 Annual Reports Questionnaire Part Three. Extent and patterns of and trends in drug use Report of the Government of: Reporting Year: reporting. Completed on (date): (dd/mm/yyyy) Please upload completed questionnaire to: https://arq.unodc.org/ The completed annual report questionnaire is due on: official March 31, 2016 For technical support, contact: for Phone Fax Email UNODC Vienna (+43-1) 26060-3914 (+43-1) 26060-5866 [email protected] Not Note: This is a printable version of the annual report questionnaire, which is in the form of an Excel spreadsheet and is designed to be completed electronically. In this printable version, definitions of key terms used in the questionnairecopy. are provided in the footnotes, whenever relevant; in the electronic version, these definitions (and additional instructions) are repeated throughout the questionnaire through the “Comments” function in Excel. The Excel spreadsheet also uses drop-down lists for some questions, allowing respondents to simply select from a list the answer that is most appropriate for their country. Sample INSTRUCTIONS The annual report questionnaire consists of the following four parts: Part One. Legislative and institutional framework; Part Two. Comprehensive approach to drug demand reduction; Part Three. Extent, patterns and trends in drug use; Part Four. Extent and patterns of and trends in drug crop cultivation and drug manufacture and trafficking This is part three of the annual report questionnaire. Respondents are asked to complete all questions. Where no data are available, this should be indicated by inserting two dashes (--) or writing "not known" in the appropriate cell. -

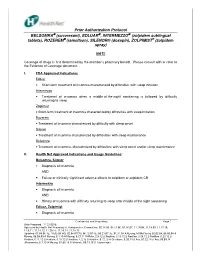

Prior Authorization Protocol BELSOMRA® (Suvorexant)

Prior Authorization Protocol BELSOMRA (suvorexant), EDLUAR , INTERMEZZO (zolpidem sublingual tablets), ROZEREM (ramelteon), SILENOR® (doxepin), ZOLPIMIST ® (zolpidem spray) NATL Coverage of drugs is first determined by the member’s pharmacy benefit. Please consult with or refer to the Evidence of Coverage document. I. FDA Approved Indications: Edluar • Short-term treatment of insomnia characterized by difficulties with sleep initiation Intermezzo • Treatment of insomnia when a middle-of-the-night awakening is followed by difficulty returning to sleep Zolpimist • Short-term treatment of insomnia characterized by difficulties with sleep initiation. Rozerem • Treatment of insomnia characterized by difficulty with sleep onset Silenor • Treatment of insomnia characterized by difficulties with sleep maintenance Belsomra • Treatment of insomnia, characterized by difficulties with sleep onset and/or sleep maintenance II. Health Net Approved Indications and Usage Guidelines: Belsomra, Silenor • Diagnosis of insomnia AND • Failure or clinically significant adverse effects to zolpidem or zolpidem CR Intermezzo • Diagnosis of insomnia AND • History of insomnia with difficulty returning to sleep after middle of the night awakening Edluar, Zolpimist • Diagnosis of insomnia Confidential and Proprietary Page 1 Date Prepared: 11.23.05JE Approved by Health Net Pharmacy & Therapeutic s Committee: 02.14.06, 04.11.06, 05.16.07, 11.19.08, 11.18.09, 11.17.10, 11.9.11, 11.14.12, 11.20.13, 11.19.14, 11.18.15 Updated: 05.09.06 JE, 10.03.06 RG, 02.08.07CM, -

Insomnia in Adults

New Guideline February 2017 The AASM has published a new clinical practice guideline for the pharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia in adults. These new recommendations are based on a systematic review of the literature on individual drugs commonly used to treat insomnia, and were developed using the GRADE methodology. The recommendations in this guideline define principles of practice that should meet the needs of most adult patients, when pharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia is indicated. The clinical practice guideline is an essential update to the clinical guideline document: Sateia MJ, Buysse DJ, Krystal AD, Neubauer DN, Heald JL. Clinical practice guideline for the pharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia in adults: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(2):307–349. SPECIAL ARTICLE Clinical Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Insomnia in Adults Sharon Schutte-Rodin, M.D.1; Lauren Broch, Ph.D.2; Daniel Buysse, M.D.3; Cynthia Dorsey, Ph.D.4; Michael Sateia, M.D.5 1Penn Sleep Centers, Philadelphia, PA; 2Good Samaritan Hospital, Suffern, NY; 3UPMC Sleep Medicine Center, Pittsburgh, PA; 4SleepHealth Centers, Bedford, MA; 5Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, NH Insomnia is the most prevalent sleep disorder in the general popula- and disease management of chronic adult insomnia, using existing tion, and is commonly encountered in medical practices. Insomnia is evidence-based insomnia practice parameters where available, and defined as the subjective perception of difficulty with sleep initiation, consensus-based recommendations to bridge areas where such pa- duration, consolidation, or quality that occurs despite adequate oppor- rameters do not exist. -

Nonbenzodiazepine Sedatives

24. Haller C, Thai D, Jacob P, Dyer JE: GHB urine concentrations after single-dose adminis- CHAPTER Nonbenzodiazepine tration in humans. J Anal Toxicol 30: 360, 2006. [PMID: 16872565] 25. Wong CG, Gibson KM, Snead O: From the street to the brain: neurobiology of the rec- Sedatives reational drug gamma-hydroxybutyric acid. Trends Pharmacol Sci 25: 29, 2004. [PMID: 184 14723976] Frank LoVecchio 26. White CM: Pharmacologic, pharmacokinetic, and clinical assessment of illicitly used γ-hydroxybutyrate. J Clin Pharmacol 57: 33, 2017. [PMID: 27198055] 27. Liakoni E, Walther F, Nickel CH, Liechti ME: Presentations to an urban emergency department in Switzerland due to acute γ-hydroxybutyrate toxicity. Scand J Trauma REFERENCES Resusc Emerg Med 24: 107, 2016. [PMID: 27581664] 28. Thai D, Dyer JE, Benowitz NL, Haller CA: Gamma-hydroxybutyrate and ethanol effects 1. Richey SM, Krystal AD: Pharmacological advances in the treatment of insomnia. Curr and interactions in humans. J Clin Psychopharm 26: 549, 2006. [PMID: 16974199] Pharm Des 17: 1471, 2011. [PMID: 21476952] 29. Miró Ò, Galicia M, Dargan P, et al: Intoxication by gamma hydroxybutyrate and related 2. http://www.digitalcitizensalliance.org/cac/alliance/content.aspx?page=Darknet. (Digital analogues: clinical characteristics and comparison between pure intoxication and that Citizens Alliance: Darknet Marketplace Watch: monitoring sales of illegal drugs on the combined with other substances of abuse. Toxicol Lett 277: 84, 2017. [PMID: 28579487] Darknet.) Accessed December 15, 2014. 30. Dietze P, Horyniak D, Agius P, et al: Effect of Intubation for gamma-hydroxybutyric acid 3. Loane C, Politis M: Buspirone: what is it all about? Brain Res 1461: 111, 2012. -

METHAQUALONE Latest Revision: February 15, 1999

METHAQUALONE Latest Revision: February 15, 1999 1. SYNONYMS CFR: Methaqualone CAS #: Base: 72-44-6 Hydrochloride: 340-56-7 Other Names: 2-Methyl-3-(2-methylphenyl)-4-(3H)-quinazolinone 2-Methyl-3-o-tolyl-4-(3H)-quinazolinone Dormogen Metolquizolone Mandrax MAOA Motolon Quaalude Sopor 2. CHEMICAL AND PHYSICAL DATA 2.1. CHEMICAL DATA Form Chemical Formula Molecular Weight Melting Point (°C) Base C16H14N2O 250.3 114-116 Hydrochloride C16H15N2OCl 286.8 255-265 2.2. SOLUBILITY Form A C E H M W Base *** S P *** PS I Hydrochloride S S I *** S PS A = acetone, C = chloroform, E = ether, H = hexane, M = methanol and W = water, VS = very soluble, FS = freely soluble, S = soluble, PS = sparingly soluble, SS = slightly soluble, VSS = very slightly soluble and I = insoluble 3. SCREENING TECHNIQUES 3.1. COLOR TESTS REAGENT COLOR PRODUCED Acidified cobalt thiocyanate Blue Fischer-Morris Pink 3.2. CRYSTAL TESTS REAGENT CRYSTALS FORMED Potassium permanganate solution Plates Sodium carbonate solution Needles 3.3. THIN-LAYER CHROMATOGRAPHY Visualization Acidified iodoplatinate solution Brown-violet Dragendorff spray Yellow-orange RELATIVE R1 COMPOUND System System System TLC6 TLC5 TLC7 mecloqualone 0.8 1.0 1.0 methaqualone 1.0 1.0 1.0 o-toluidine 1.3 1.6 1.6 3.4. GAS CHROMATOGRAPHY Methaqualone is a thermally stable compound well suited for gas chromatography. It may however, have a similar retention time with cocaine in certain temperature programs. Method MEQ-GCS1 Instrument: Gas chromatograph operated in split mode with FID Column: 5% phenyl/95% methyl silicone 12 m x 0.2 mm x 0.33 µm film thickness Carrier gas: Helium at 1.0 mL/min Temperatures: Injector: 270°C Detector: 280°C Oven program: 1) 175°C initial temperature for 1.0 min 2) Ramp to 275°C at 15°C/min 3) Hold final temperature for 3.0 min Injection Parameters: Split Ratio = 60:1, 1 µL injected Samples are to be dissolved in chloroform and filtered. -

Anxiety Disorders, Insomnia, PTSD, OCD

2/3/2020 Anxiety Disorders, Insomnia, PTSD, OCD Steven L. Dubovsky, M.D. 1 2/3/2020 Basic Benzodiazepine Structure R1 R2 N C R7 C R3 C=N R4 R2′ Benzodiazepine R1 R2 R3 R7 R2′ Alprazolam Fused triazolo ring -H -Cl -H Chlordiazepoxide - -NHCH3 -H -Cl -H Clonazepam -H =O -H NO2 -Cl Diazepam -CH3 =O -H -Cl -H 2 2/3/2020 GABA-Benzodiazepine Receptor Complex GABA BZD Cl- 3 2/3/2020 Benzodiazepine Action GABA Cl- + + BZD - Cl- Inverse agonist Flumazenil • Benzodiazepine receptor antagonist R1 R2 • Therapeutic uses: C N – Benzodiazepine overdose R3 C R7 N C – Reversal of conscious sedation R4 = – Reversal of hepatic encephalopathy symptoms R2′ – Facilitation of benzodiazepine withdrawal • Can provoke withdrawal and induce anxiety 4 2/3/2020 BZD Receptor Subtypes • Type 1: Limbic system, locus coeruleus – Anxiolytic • Type 2: Cortex, pyramidal cells – Muscle relaxation, anticonvulsant, CNS depression, sedation, psychomotor impairment • Type 3: Mitochondria, periphery – Dependence, withdrawal BZD Features • Potency – High potency: Midazolam (Versed), alprazolam (Xanax), triazolam (Halcion) – Low potency: Chlordiazepoxide (Librium), flurazepam (Dalmane) • Lipid solubility – High solubility: Alprazolam, diazepam (Valium) – Low solubility: Lorazepam (Ativan), chlordiazepoxide (Librium) • Elimination half-life – Long half-life: Diazepam, chlordiazepoxide – Short half-life: Alprazolam, midazolam 5 2/3/2020 Potency • High potency – Smaller dose to produce same effect – More receptor occupancy – More intense withdrawal • Low potency – Higher doses used -

Report on the Deliberation Results February 5, 2010 Evaluation And

Report on the Deliberation Results February 5, 2010 Evaluation and Licensing Division, Pharmaceutical and Food Safety Bureau Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare [Brand name] Rozerem Tablets 8 mg [Non-proprietary name] Ramelteon (JAN*) [Applicant] Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited [Date of application] February 29, 2008 [Results of deliberation] In the meeting held on January 29, 2010, the First Committee on New Drugs concluded that the product may be approved and that this result should be presented to the Pharmaceutical Affairs Department of the Pharmaceutical Affairs and Food Sanitation Council. The product is not classified as a biological product or a specified biological product, the re-examination period is 8 years, and the drug substance is classified as a powerful drug and the drug product is not classified as a poisonous drug or a powerful drug. *Japanese Accepted Name (modified INN) This English version of the Japanese review report is intended to be a reference material to provide convenience for users. In the event of inconsistency between the Japanese original and this English translation, the former shall prevail. The PMDA will not be responsible for any consequence resulting from the use of this English version. Review Report January 15, 2010 Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency The results of a regulatory review conducted by the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency on the following pharmaceutical product submitted for registration are as follows. [Brand name] Rozerem Tablets 8 mg [Non-proprietary name]