Australian Coal Alliance Submission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gosford City Centre Masterplan the Gosford Challenge Gosford City Centre Masterplan

City, Our destiny Gosford City Centre Masterplan The Gosford ChallenGe Gosford City Centre Masterplan r City, u O destiny a World Class reGional Waterfront City r City, iii u O destiny The Gosford ChallenGe Gosford City Centre Masterplan acknowledgments JOINT PROJeCt SPONSORS DESIGn TEAM Gosford City Council land and property Gosford Challenge team Clr Chris Holstein Management authority Colleen Worthy-Jennings Mayor Hon Tony Kelly MHR Stephen Fairnham Clr Craig Doyle Warwick Watkins Duncan Clarke Deputy Mayor Graham Harding Helen Polkinghorne Clr Chris Burke Brett Phillips John Tilston Clr Peter Freewater Stewart Veitch Barbara Cruise Clr Amy Houston Robert Eyre Clr Terri Latella Scott Burton Clr Jim Macfadyen Steve Green Clr Laurie Maher Sue Verhoek Clr Vicki Scott Kerr Partnering Clr Jeff Strickson Cox Architects and Planners Peter Wilson Patrick Condon Stephen Glen Rob Lane Gary Chestnut Aurecon Rod Williams Arup Nic Pasternatsky Oculus Terry Thirlwell teaming with ideas r City, u O destiny Contents 1 GROWING A REGIONAL CITY 2 4 MAKING IT HAPPEN 92 1.1 gosford as a regional city 3 4.1 implementation plan 93 1.2 greater metropolitan context 4 4.2 the beginning - two priority areas 96 1.3 regional context 5 APPENDICES 1.4 local context 6 appendix 1 sustainability 102 1.5 attributes of a regional city 8 appendix 2 regional benchmarks 110 1.6 purpose of a masterplan 10 appendix 3 retail and commercial market 114 1.7 the journey 12 appendix 4 participants 116 1.8 planning context 14 1.9 key strategic opportunities 15 2 SPATIAL FRAMEWORK 16 2.1 the city framework 16 2.2 the masterplan 18 2.3 five precincts of activity 20 3 MASTERPLAN ELEMENTS 48 3.1 connecting places 50 3.2 activate the city 56 3.3 responsive built form 60 3.4 generate jobs and new enterprises 64 3.5 living in the city 72 3.6 access and movement 76 3.7 sustaining the city (enhancing the natural environment) 86 note: diagrams of future development are concept only. -

Environment and Communications Legislation Committee Answers to Questions on Notice Environment Portfolio

Senate Standing Committee on Environment and Communications Legislation Committee Answers to questions on notice Environment portfolio Question No: 3 Hearing: Additional Estimates Outcome: Outcome 1 Programme: Biodiversity Conservation Division (BCD) Topic: Threatened Species Commissioner Hansard Page: N/A Question Date: 24 February 2016 Question Type: Written Senator Waters asked: The department has noted that more than $131 million has been committed to projects in support of threatened species – identifying 273 Green Army Projects, 88 20 Million Trees projects, 92 Landcare Grants (http://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/3be28db4-0b66-4aef-9991- 2a2f83d4ab22/files/tsc-report-dec2015.pdf) 1. Can the department provide an itemised list of these projects, including title, location, description and amount funded? Answer: Please refer to below table for itemised lists of projects addressing threatened species outcomes, including title, location, description and amount funded. INFORMATION ON PROJECTS WITH THREATENED SPECIES OUTCOMES The following projects were identified by the funding applicant as having threatened species outcomes and were assessed against the criteria for the respective programme round. Funding is for a broad range of activities, not only threatened species conservation activities. Figures provided for the Green Army are approximate and are calculated on the 2015-16 indexed figure of $176,732. Some of the funding is provided in partnership with State & Territory Governments. Additional projects may be approved under the Natinoal Environmental Science programme and the Nest to Ocean turtle Protection Programme up to the value of the programme allocation These project lists reflect projects and funding originally approved. Not all projects will proceed to completion. -

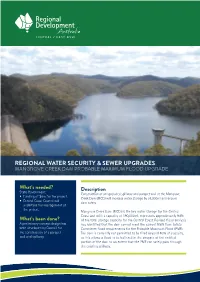

Mangrove Creek Dam Probable Maximum Flood Upgrade

REGIONAL WATER SECURITY & SEWER UPGRADES MANGROVE CREEK DAM PROBABLE MAXIMUM FLOOD UPGRADE What’s needed? State Government: Description Construction of an upgraded spillway and parapet wall at the Mangrove • Funding of $6m for the project. Creek Dam (MCD) will increase water storage by 38,000ml and ensure • Central Coast Council will dam safety. undertake the management of the project. Mangrove Creek Dam (MCD) is the key water storage for the Central Coast and with a capacity of 190,000ml, represents approximately 94% What’s been done? of the total storage capacity for the Central Coast. Revised flood analysis A preliminary concept design has has identified that the dam cannot meet the current NSW Dam Safety been developed by Council for Committee flood requirements for the Probable Maximum Flood (PMF). the construction of a parapet The dam is currently not permitted to be filled beyond 80% of capacity, wall and spillway. as this allows a flood to be buffered in the airspace of the unfilled portion of the dam to an extent that the PMF can safely pass through the existing spillway. Description (cont.) Benefits Construction of a parapet wall and spillway improvements will • Increase water storage capacity of the Central Coast (15 allow the PMF to pass and increase capability storage to 100%. months additional supply at current demand). This will ensure the safety of the dam and the downstream • Increase the ability to supply water to the Hunter under community and provide an additional 38,000ml of storage, the the Hunter Central Coast Pipeline agreement which is equivalent of 15 months water supply. -

Settlement of the Tuggerah Lakes

Settlement of the Tuggerah Lakes The ecological history of the Tuggerah Lakes over the last 200 years is closely linked to the pattern of European settlement both around the lakes and within the upper catchment. As settlement spread throughout the district, activities such as the clearing of land, logging, fishing and urban development have all had impacts on the ecology of the lakes. To understand when each of these impacts occurred, the settlement of the Tuggerah Lakes and its catchment has been divided into four broad time periods. These are; • Aboriginal settlement • The first European settlers (1820s – 1870s) • Settlement after the opening of the railway (1880s – 1950s) • Urban Development (1960s – 1990s) Historical documents which provide an insight into the rates of settlement and associated activities during each of these time periods, are presented in the following sections. Table 1 provides a summary of some key dates in the development of the region. Table 1. Significant events in the development of the Tuggerah Lakes and its catchment Date Activity 1825 First settlers arrived. Early 1830s Logging commenced in the upper catchment, principally for cedar. Early 1830s Felton Mathews surveyed the district. 1832 The Great North Road was opened, principally as a means of providing access to the Hunter District from Sydney. There were two branches from this road into Wyong. 1830s Cabbage Tree Harbour provided a shipping point for cedar from the 1830s onwards. Gosford was another such departure point. Early1850s Hargraves residence at Noraville constructed using cedar from the valleys behind Wyong. 1854 Jane Taylor acquired all the land of what is now The Entrance. -

NSW Department of Industry Publication

LOWER HUNTER WATER PLAN Monitoring, Evaluation, Reporting and Improvement 2019 Annual Evaluation December 2019 VERSION 0.2 NSW Department of Planning, Industry & Environment | dpie.nsw.gov.au Published by NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment dpie.nsw.gov.au Title: Monitoring, Evaluation, Reporting and Improvement 2019 Annual Evaluation More information Erin Toner, Sogol Ghobad and Bridie Halse Lower Hunter Water Plan Project Team / Newcastle Acknowledgements The Lower Hunter Water Plan Project Team at Department of Planning, Industry and Environment thank Hunter Water and Central Coast Council for their continued cooperation during the collation of the Monitoring, Evaluation, Reporting and Improvement process. © State of New South Wales through Department of Planning, Industry and Environment 2019. You may copy, distribute, display, download and otherwise freely deal with this publication for any purpose, provided that you attribute the Department of Planning, Industry and Environment as the owner. However, you must obtain permission if you wish to charge others for access to the publication (other than at cost); include the publication in advertising or a product for sale; modify the publication; or republish the publication on a website. You may freely link to the publication on a departmental website. Disclaimer: The information contained in this publication is based on knowledge and understanding at the time of writing (November 2019) and may not be accurate, current or complete. The State of New South Wales (including the NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment), the author and the publisher take no responsibility, and will accept no liability, for the accuracy, currency, reliability or correctness of any information included in the document (including material provided by third parties). -

Nsw Estuary and River Water Levels Annual Summary 2015-2016

NSW ESTUARY AND RIVER WATER LEVELS ANNUAL SUMMARY 2015–2016 Report MHL2474 November 2016 prepared for NSW Office of Environment and Heritage This page intentionally blank NSW ESTUARY AND RIVER WATER LEVELS ANNUAL SUMMARY 2015–2016 Report MHL2474 November 2016 Peter Leszczynski 110b King Street Manly Vale NSW 2093 T: 02 9949 0200 E: [email protected] W: www.mhl.nsw.gov.au Cover photograph: Coraki photo from the web camera, Richmond River Document control Issue/ Approved for issue Author Reviewer Revision Name Date Draft 21/10/2016 B Tse, MHL S Dakin, MHL A Joyner 26/10/2016 Final 04/11/2016 M Fitzhenry, OEH A Joyner 04/11/2016 © Crown in right of NSW through the Department of Finance, Services and Innovation 2016 The data contained in this report is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 licence. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 Manly Hydraulics Laboratory and the NSW Office of Environment and Heritage permit this material to be reproduced, for educational or non-commercial use, in whole or in part, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. While this report has been formulated with all due care, the State of New South Wales does not warrant or represent that the report is free from errors or omissions, or that it is exhaustive. The State of NSW disclaims, to the extent permitted by law, all warranties, representations or endorsements, express or implied, with regard to the report including but not limited to, all implied warranties of merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, or non-infringement. -

Central Coast Plateau Tourism Plan – Calais Consultants 2 Executive Summary

Central Coast Plateau Tourism Plan October 2006 Calais Consultants Central Coast Plateau Tourism Plan October 2006 Prepared by Satwant Calais Calais Consultants DISCLAIMER The statements, information, opinions, schedules and forecasts expressed and detailed in this Plan are intended as a guide only. Every care has been taken to ensure that data and analysis are as accurate as possible. The consultants take no responsibility for any errors or omissions in fact or interpretation. Further detailed internal evaluation is recommended before implementation, especially where results are separated from dependencies or newly combined into other alternatives. Such actions will require the new outcomes to be adapted, revised and verified, by the individual(s) administering or implementing the variation. The document is collaboration between the client and the consultant. All information is based on the best and most recent information collected. But as this document involves various forecasts, which can be affected by a number of unforeseen or unpredictable variables, then should more than 6 months pass it would be good business practice to revise the forecasts in light of seasonality or known changes in the working environment. Even so no warranty can or is given that the results will in fact occur. Neither Calais Consultants nor any person involved in the preparation of this document give any warranties as to the contents nor accept any contractual, tortuous or other form of liability for any consequences, loss or damage which may arise as a result of any person acting upon or using the document.” This study was supported by the Department of State and Regional Development Central Coast Plateau Tourism Plan – Calais Consultants 2 Executive Summary Central Coast Plateau Inc. -

Central Coast Drinking Water Source Documents for HSC Chemistry (Module 9.4: Chemical Monitoring and Management)

Central Coast Drinking Water Source Documents for HSC Chemistry (Module 9.4: Chemical monitoring and management) 1. Introduction This PDF document, Central Coast Drinking Water , addresses the following statement on page 61 of the NSW HSC Chemistry Syllabus: “gather, process and present information on the features of the local town water supply in terms of - catchment area - possible sources of contamination in this catchment - chemical tests available to determine levels and types of contaminants - physical and chemical processes used to purify water - chemical additives in the water and the reasons for the presence of these additives ” (Source: NSW HSC Chemistry Syllabus, Section 9.4 Chemical Monitoring and Management). Its purpose is to complement the excellent teaching/learning module 'Water Quality: HSC Chemistry ' produced by the Sydney Catchment Authority (see SCA at http://hsc.sca.nsw.gov.au/chemistry/introduction ). Specifically, this document presents information for students and teachers on the Central Coast of NSW; information about the local water supply that will enable students to address the Chemistry Syllabus dot points in familiar terms and with relevant examples. This document does not attempt to deal with the broader issues of water testing purposes and methodology prescribed in the Syllabus. These issues are already well treated in the SCA module. Rather, the materials here are selected secondary sources that will assist Central Coast students to better understand the particular features of their Water Supply system and the regimes in place to monitor and ensure that high quality drinking water is available for all residents. These secondary sources should enable Central Coast students to complete the kind of assessment task suggested on the SCA webpage http://hsc.sca.nsw.gov.au/chemistry/drinking_water/report . -

Mangrove Creek Dam the Central Coast Has the Third Largest Urban Water Supply System in New South Wales

Mangrove Creek Dam The Central Coast has the third largest urban water supply system in New South Wales. The water supply system serves the region’s population of almost 300,000 people, delivering water to about 125,000 homes and businesses. The system currently incorporates three dams, three weirs, three water treatment plants, over 50 reservoirs, and more than 2,000 kilometres of pipelines. Mangrove Creek Dam 2 /DNH0DFTXDULH&LW\ Hunter Connection Mangrove Creek Dam Boomerang Creek Tunnel Mardi-Mangrove Link Lower Wyong Kanwal River Weir Reservoir Mardi Water Mardi Dam Treatment Plant Mardi Groundwater Bore Ourimbah Creek Weir Mangrove Creek Weir Tuggerah Reservoir Mangrove Creek Ourimbah Groundwater Bores Mangrove Mooney Mooney Dam Groundwater Creek Bore Fields Pipeline Narara Groundwater Bores Somersby Western Connection Groundwater Bore Coastal Kariong Connection Reservoir Somersby Water Treatment Plant Woy Woy Groundwater Bore Fields Woy Woy Water Treatment Plant Hornsby Shire Water Dam Tunnel Into the water Treatment supply system Plant Weir Reservoir Pipeline Groundwater Bore Mangrove Creek Wyong River Mardi Dam Mangrove Creek Dam Catchment Catchment Catchment Weir Catchment Ourimbah Creek Porters Creek Mooney Mooney Dam Catchment Catchment Catchment 3 Mangrove Creek Dam is the Central Coast’s largest dam, located 50km north-west of Gosford in a narrow valley. Constructed between 1978 and 1982, Mangrove Creek Dam is a concrete the dam provides 93 percent of the faced rockfill dam that provides region’s water storage with a maximum on-stream storage of water. The dam capacity of 190,000 million litres has a catchment area of 101 square of water. kilometres and provides water to both Gosford City and Wyong Shire. -

National Recovery Plan Magenta Lilly Pilly Syzygium Paniculatum

National Recovery Plan Magenta Lilly Pilly Syzygium paniculatum June 2012 © Copyright State of NSW and the Office of Environment and Heritage, Department of Premier and Cabinet. With the exception of illustrations, the Office of Environment and Heritage, Department of Premier and Cabinet and State of NSW are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial use, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specific permission is required for the reproduction of illustrations. Published by: Office of Environment and Heritage NSW 59 Goulburn Street, Sydney NSW 2000 PO Box A290, Sydney South NSW 1232 Phone: (02) 9995 5000 (switchboard) Phone: 131 555 (environment information and publications requests) Phone: 1300 361 967 (national parks, climate change and energy efficiency information, and publications requests) Fax: (02) 9995 5999 TTY: (02) 9211 4723 Email: [email protected] Website: www.environment.nsw.gov.au Report pollution and environmental incidents Environment Line: 131 555 (NSW only) or [email protected] See also www.environment.nsw.gov.au Requests for information or comments regarding the recovery program for Magenta Lilly Pilly are best directed to: The Magenta Lilly Pilly Coordinator Biodiversity Assessment and Conservation Section, North East Branch Conservation and Regulation Division Office of Environment and Heritage Department of Premier and Cabinet Locked Bag 914 Coffs Harbour NSW 2450 Phone: 02 6651 5946 Cover illustrator: Lesley Elkan © Botanic Gardens Trust ISBN 978 1 74122 786 4 June 2012 DECC 2011/0259 Recovery Plan Magenta Lilly Pilly Recovery Plan for Magenta Lilly Pilly Syzygium paniculatum Foreword This document constitutes the national recovery plan for Magenta Lilly Pilly (Syzygium paniculatum) and, as such, considers the conservation requirements of the species across its known range. -

Tuggerah Estuary Management Study

Management Status 2.2.7 Sewerage Management The reticulated sewerage system of Wyong Shire is generally confined to the urban areas, with septic systems being used in the rural areas. The reticulated system has built-in failure points where sewage can overflow in case of pump failure, or similar problems. Generally, the overflow points will be adjacent to stormwater systems or a waterway. Given that sewage is high in nutrients and turbid, it can have a significant impact on downstream environments. Septic systems, if well contained and frequently serviced, do not necessarily increase sediment and nutrient loads. However, poorly maintained systems can overflow or fracture, leaching nutrients and sediment into surface and groundwater flows. The reticulated system overflows relatively infrequently. However, it should be remembered that the reticulated system is composed of both a domestic sewerage line and trade waste line. Both lines have an overflow capacity, which allows discharge into the stormwater system. A significant overflow to Tumbi Creek occurred in May 2003, which saw 72,000L of effluent discharged following a combined pump/power failure at a pumping station (WSC, 2003a). Although unintentional and quickly rectified, this kind of discharge can have significant nutrient impacts on downstream environments. Four non-significant sewage overflows occurred in the Wyong system during 2001/02. Two were due to blockages of mains and two due to power failure at pump stations (WSC, 2002). The overflow points are sometimes located adjacent to sensitive environmental areas. For example, the overflow at Fishburn Drain can discharge sewage and trade waste to the Porters Creek wetland. -

THE BENTHIC FAUNA of the TUGGERAH LAKES B. J. Powis

THE BENTHIC FAUNA OF THE TUGGERAH LAKES B. J. Powis This thesis is submitted for the Degree of Master of Science at University of New South Wales JULY, 1975. UNIVERSITY CF N.3.W.,, 55701 1 3. JAN. 7 6 LIBRARY This is to certify that this thesis has not been submitted for a higher degree to any other university or institution. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. R.J. MacIntyre for his continued guidance and advice throughout this project. This study was financed by the Electricity Commission of N.S.W. and the Wyong Council. I would like to thank them for this assistance. I would also like to thank the Electricity Commission for their cooperation and assistance in the collection of field material. I am grateful to the following people for their assistance in the identification of the various taxonomic groups: Dr. Pat Hutchings (polychaetes), Cathy Drummond (crustaceans) and Dr. Winston Ponder (molluscs). I am also very grateful to Leon Collett who has given a great deal of assistance in many areas of this study, especially with the computer analysis. With regard to the use of computer programs I would like to thank Alan Collins who has given a great deal of assistance with the computer analysis. Thanks are also due to Professor Stephenson for his advice on statistical procedures. Considerable assistance has been given in the collection of samples by Bill Jefferson, Stephen Sparkes, Gary Bebbington, Bruce Hodgson and Ray Wallis. For proof reading and grammatical correction of the text I would like to thank Helen Stoddart, Charles Pregenzer, Harry Booth and Paul Kloedon.