M U Kshidabad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Banians in the Bengal Economy (18Th and 19Th Centuries): Historical Perspective

Banians in the Bengal Economy (18th and 19th Centuries): Historical Perspective Murshida Bintey Rahman Registration No: 45 Session: 2008-09 Academic Supervisor Dr. Sharif uddin Ahmed Supernumerary Professor Department of History University of Dhaka This Thesis Submitted to the Department of History University of Dhaka for the Degree of Master of Philosophy (M.Phil) December, 2013 Declaration This is to certify that Murshida Bintey Rahman has written the thesis titled ‘Banians in the Bengal Economy (18th & 19th Centuries): Historical Perspective’ under my supervision. She has written the thesis for the M.Phil degree in History. I further affirm that the work reported in this thesis is original and no part or the whole of the dissertation has been submitted to, any form in any other University or institution for any degree. Dr. Sharif uddin Ahmed Supernumerary Professor Department of History Dated: University of Dhaka 2 Declaration I do declare that, I have written the thesis titled ‘Banians in the Bengal Economy (18th & 19th Centuries): Historical Perspective’ for the M.Phil degree in History. I affirm that the work reported in this thesis is original and no part or the whole of the dissertation has been submitted to, any form in any other University or institution for any degree. Murshida Bintey Rahman Registration No: 45 Dated: Session: 2008-09 Department of History University of Dhaka 3 Banians in the Bengal Economy (18th and 19th Centuries): Historical Perspective Abstract Banians or merchants’ bankers were the first Bengali collaborators or cross cultural brokers for the foreign merchants from the seventeenth century until well into the mid-nineteenth century Bengal. -

Multi- Hazard District Disaster Management Plan

MULTI –HAZARD DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN, BIRBHUM 2018-2019 MULTI – HAZARD DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN BIRBHUM - DISTRICT 2018 – 2019 Prepared By District Disaster Management Section Birbhum 1 MULTI –HAZARD DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN, BIRBHUM 2018-2019 2 MULTI –HAZARD DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN, BIRBHUM 2018-2019 INDEX INFORMATION 1 District Profile (As per Census data) 8 2 District Overview 9 3 Some Urgent/Importat Contact No. of the District 13 4 Important Name and Telephone Numbers of Disaster 14 Management Deptt. 5 List of Hon'ble M.L.A.s under District District 15 6 BDO's Important Contact No. 16 7 Contact Number of D.D.M.O./S.D.M.O./B.D.M.O. 17 8 Staff of District Magistrate & Collector (DMD Sec.) 18 9 List of the Helipads in District Birbhum 18 10 Air Dropping Sites of Birbhum District 18 11 Irrigation & Waterways Department 21 12 Food & Supply Department 29 13 Health & Family Welfare Department 34 14 Animal Resources Development Deptt. 42 15 P.H.E. Deptt. Birbhum Division 44 16 Electricity Department, Suri, Birbhum 46 17 Fire & Emergency Services, Suri, Birbhum 48 18 Police Department, Suri, Birbhum 49 19 Civil Defence Department, Birbhum 51 20 Divers requirement, Barrckpur (Asansol) 52 21 National Disaster Response Force, Haringahata, Nadia 52 22 Army Requirement, Barrackpur, 52 23 Department of Agriculture 53 24 Horticulture 55 25 Sericulture 56 26 Fisheries 57 27 P.W. Directorate (Roads) 1 59 28 P.W. Directorate (Roads) 2 61 3 MULTI –HAZARD DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN, BIRBHUM 2018-2019 29 Labpur -

Slowly Down the Ganges March 6 – 19, 2018

Slowly Down the Ganges March 6 – 19, 2018 OVERVIEW The name Ganges conjures notions of India’s exoticism and mystery. Considered a living goddess in the Hindu religion, the Ganges is also the daily lifeblood that provides food, water, and transportation to millions who live along its banks. While small boats have plied the Ganges for millennia, new technologies and improvements to the river’s navigation mean it is now also possible to travel the length of this extraordinary river in considerable comfort. We have exclusively chartered the RV Bengal Ganga for this very special voyage. Based on a traditional 19th century British design, our ship blends beautifully with the timeless landscape. Over eight leisurely days and 650 kilometres, we will experience the vibrant, complex tapestry of diverse architectural expressions, historical narratives, religious beliefs, and fascinating cultural traditions that thrive along the banks of the Ganges. Daily presentations by our expert study leaders will add to our understanding of the soul of Indian civilization. We begin our journey in colourful Varanasi for a first look at the Ganges at one of its holiest places. And then by ship we explore the ancient Bengali temples, splendid garden-tombs, and vestiges of India’s rich colonial past and experience the enduring rituals of daily life along ‘Mother Ganga’. Our river journey concludes in Kolkatta (formerly Calcutta) to view the poignant reminders of past glories of the Raj. Conclude your trip with an immersion into the lush tropical landscapes of Tamil Nadu to visit grand temples, testaments to the great cultural opulence left behind by vanished ancient dynasties and take in the French colonial vibe of Pondicherry. -

The Garden of India; Or, Chapters on Oudh History and Affairs

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES ^ AMSTIROAM THE GARDEN OF INDIA. THE GARDEN or INDIA; OR CHAPTERS ON ODDH HISTORY AND AFFAIRS. BY H. C. IHWIN, B.A. OxoN., B.C.S. LOHf D N: VV. H. ALLEN <t CO., 13 WATERLOO TLACE. PUBLISH KUS TO THK INDIA OKKICK. 1880. Mil rtg/ito reMrvedij LONDON : PRINTP.D BT W. H. ALLKN AND CO , 13 iVATERLOO PLACK, S.W. D5 7a TO MI BROTHER OFFICERS OF THE OUDH COMMISSION I BEG LEAVE TO INSCRIBE THIS LITTLE BOOK WITH A PROFOUND SENSE OF ITS MANY DEFICIENCIES BUT IN THE HOPE THAT HOWEVER WIDELY SOME OP THEM MAY DISSENT FROM NOT A FEW OF THE OPINIONS I HAVE VENTURED TO EXPRESS THEY WILL AT LEAST BELIEVE THAT THESE ARE INSPIRED BY A SINCERE LOVE OF THE PROVINCE AND THE PEOPLE WHOSE WELFARE WE HAVE ALL ALIKE AT HEART. a 3 : ' GHrden of India I t'adinjj flower ! Withers thy bosom fair ; State, upstart, usurer devour What frost, flood, famine spare." A. H. H. "Ce que [nous voulonsj c'est que le pauvre, releve de sa longue decheance, cesse de trainer avec douleur ses chaines hereditaires, d'etre an pur instrument de travail, uue simple matiere exploitable Tout effort qui ne produirait pas ce resultat serait sterile ; toute reforme dans les choses presentes qui n'aboutirait point a cette reforme fonda- meutale serait derisoire et vaine." Lamennais. " " Malheur aux resignes d'aujourd'hui ! George Sand. " The dumb dread people that sat All night without screen for the night. All day mthout food for the day, They shall give not their harvest away, They shall eat of its frtiit and wax fat They shall see the desire of their sight, Though the ways of the seasons be steep, They shall climb mth face to the light, Put in the sickles and reap." A. -

An Analysis of Online Discursive Battle of Shahbag Protest 2013 in Bangladesh

SEXISM IN ‘ONLINE WAR’: AN ANALYSIS OF ONLINE DISCURSIVE BATTLE OF SHAHBAG PROTEST 2013 IN BANGLADESH By Nasrin Khandoker Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment for the degree of Master of Arts in Gender Studies. Supervisor: Professor Elissa Helms Budapest, Hungary 2014 CEU eTD Collection I Abstract This research is about the discursive battle between radical Bengali nationalists and the Islamist supporters of accused and convicted war criminals in Bangladesh where the gendered issues are used as weapons. In Bangladesh, the online discursive frontier emerged from 2005 as a continuing battle extending from the 1971 Liberation War when the punishment of war criminals and war rapists became one of the central issues of political and public discourse. This online community emerged with debate about identity contest between the Bengali nationalist ‘pro-Liberation War’ and the ‘Islamist’ supporters of the accused war criminals. These online discourses created the background of Shahbag protest 2013 demanding the capital punishment of one convicted criminal and at the time of the protest, the online community played a significant role in that protest. In this research as a past participant of Shahbag protest, I examined this online discourse and there gendered and masculine expression. To do that I problematized the idea of Bengali and/or Muslim women which is related to the identity contest. I examined that, to protest the misogynist propaganda of Islamist fundamentalists in Bangladesh, feminists and women’s organizations are aligning themselves with Bengali nationalism and thus cannot be critical about the gendered notions of nationalism. I therefore, tried to make a feminist scholarly attempt to be critical of the misogynist and gendered notion of both the Islamists and Bengali nationalists to contribute not only a critical examination of masculine nationalist rhetoric, but will also to problematize that developmentalist feminist approach. -

Patna –Azimabad As Socio-Cultural Centre (Part-2) M.A.(History) Sem-2 Paper Cc:7

PATNA –AZIMABAD AS SOCIO-CULTURAL CENTRE (PART-2) M.A.(HISTORY) SEM-2 PAPER CC:7 DR. MD. NEYAZ HUSSAIN ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR & HOD PG DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY MAHARAJA COLLEGE, VKSU ARA (BIHAR) PATNA –AZIMABAD AS SOCIO-CULTURAL CENTRE The town got a new name-Azimabad- and increased eminence towards the end of Mughal emperor Aurangzeb’s reign (1658-1707), and during the subahdari of his favourite grandson Prince Azim (d. 1712). The prince got the emperor’s permission to rename the town after himself, around 1704. It may be clarified here that the new name was after the Prince’s personal name, Azim, not his title, ‘Azimu’s Shan’, which he got later in the reign of his father Bahadur Shah (1707-12). The pargan a was also re-named Azimabad , as was the name of the mint. Coins bearing the now mint town, Azimabad, are still available from the year 1705-06 onwards. PATNA –AZIMABAD AS SOCIO-CULTURAL CENTRE The Prince got many public buildings constructed or renovated , established charitable institutions and sarais (inns), and encouraged eminent scholars and skilled persons to come and settle in the town. He is said to have made administrative arrangements from the division of the town into different wards, named after the people of different racial groups living there, such as Lodikatra, Mughalpura, etc. or the professional groups settled there, such as Zargartola (embroidery workers’ quarters), Mir Shikar Toli (Bird-Hunters, Falconers, etc.). The Prince wanted to make Azimabad ‘a second Delhi’ . Due to the political upheavals (1707-22) and the blood-bath PATNA –AZIMABAD AS SOCIO-CULTURAL CENTRE at Delhi(1738-39 , Nadir Shah’s sack of Delhi), there was exodus from there, and part of it flowed down to Azimabad. -

Natore Raj - Its Rise, Stability and Estate Management

96 Chapter-HI Natore Raj - Its Rise, Stability and Estate Management Natore is situated near the main road leading to Dhaka from Rajshahi. It is 30 miles east of Rajshahi. Natore town stands on the Narad river at the degree of latitude 24-6" north and 89-1 "east'. Natore was an important administrative central point during the reign of the Nawabs of Bengal. At the time of the British regime Natore was an important town of Rajshahi district. Natore had great importance as a business center. A great number of Europeans lived at Natore. In 1825 the district head quarter was shifted from Natore to Rampur-Boalia(Rajshahi) because the river Narod was silted up and dieses like malaria and dengu prevailed terribly^ . To realize the historical importance of Natore, it was made a subdivision in 1829 \ This historical Natore was the capital of Natore Raj family Natore and Natore Raj family were related inseparably. The glory of this place faded since the time of the downfall of the Natore Raj Family. Kamdev Moitra (Ray) was the ancestor of Natore Raj Family. At the beginning of tenth century, the Hindu Raja Adisur of Chandra family brought five well versed Brahmins in Bengal from Kanyakubja. This five persons were Narayan of Sandilya lineage, Dharadhar of Batsa lineage, Gautam of Bharadwaj lineage, and Parasar of Sadhan lineage and Susenmani of Kasyapa lineage. Kamdev Moitra was a member of the later generation of Susenmani of Kasyapa lineage". Kamdev Moitra was the tahsilder at Baruihati- Pargana under Raja Naranarayan Thakur of Puthia\ His dwelling place was at the village Amhati situated near Natore town. -

Udânavarga: a Collection of Verses from the Buddhist Canon

V-Z.^^ LIBRARY OF THE THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY PRINCETON, N. J. ' Division XjXrrS^ I Section .\Xj.rX: l\ I vJ i g,Cv — — TRUBNER'8 ORIENTAL SERIES. " A knowledge of the commonplace, at least, of Oriental literature, philo- sojihy, and religion is as necessary to the general reader of the present daj' as an acquaintance with the Latin and Gi-eek classics was a generation or so ago. Immense strides have been made within the present century in tliese branches of learning; Sanskrit has been brought within the range of accurate philology, and its invaluable ancient literature thoroughly investigated ; the language and sacred books of the Zoi'oastrians have been laid bare ; Egyptian, Assyrian, and other records of the remote past have been deciphered, and a group of scholars speak of still more recondite Accadian and Hittite monu- ments ; but the results of all the scliolarship that has been devoted to these subjects have been almost inaccessible to the public because they were con- tained for the most part in learned or expensive works, or scattered through- out the numbers of scientific periodicals. Messrs. Tkubneu & Co., in a spirit of enterpiise wliich does them infinite credit, have determined to supply the constantly-increasing want, and to give in a popular, or, at least, a compre- hensive form, all this mass of knowledge to the world." Times. NOW BEADY, Post 8vo, lip. 568, with Map, cloth, price 16s. THE INDIAN EMPIRE : ITS HISTORY, PEOPLE, AND PRODUCTS. Being a revised form of the article "India," in the "Imperial Gazetteer," remodelled into chapters, brought up to date, and incorporating the general results of the Census of 1881. -

District Handbook Murshidabad

CENSUS 1951 W.EST BENGAL DISTRICT HANDBOOKS MURSHIDABAD A. MITRA of the Indian Civil Service, Superintendent ot Census OPerations and Joint Development Commissioner, West Bengal ~ted by S. N. Guha Ray, at Sree Saraswaty Press Ltd., 32, Upper Circular Road, Calcutta-9 1953 Price-Indian, Rs. 30; English, £2 6s. 6<1. THE CENSUS PUBLICATIONS The Census Publications for West Bengal, Sikkim and tribes by Sudhansu Kumar Ray, an article by and Chandernagore will consist of the following Professor Kshitishprasad Chattopadhyay, an article volumes. All volumes will be of uniform size, demy on Dbarmapuja by Sri Asutosh Bhattacharyya. quarto 8i" x II!,' :- Appendices of Selections from old authorities like Sherring, Dalton,' Risley, Gait and O'Malley. An Part lA-General Report by A. Mitra, containing the Introduction. 410 pages and eighteen plates. first five chapters of the Report in addition to a Preface, an Introduction, and a bibliography. An Account of Land Management in West Bengal, 609 pages. 1872-1952, by A. Mitra, contajning extracts, ac counts and statistics over the SO-year period and Part IB-Vital Statistics, West Bengal, 1941-50 by agricultural statistics compiled at the Census of A. Mitra and P. G. Choudhury, containing a Pre 1951, with an Introduction. About 250 pages. face, 60 tables, and several appendices. 75 pages. Fairs and Festivals in West Bengal by A. Mitra, con Part IC-Gener.al Report by A. Mitra, containing the taining an account of fairs and festivals classified SubSidiary tables of 1951 and the sixth chapter of by villages, unions, thanas and districts. With a the Report and a note on a Fertility Inquiry con foreword and extracts from the laws on the regula ducted in 1950. -

Affliated Madaris

MULHAQA MADARIS DARUL ULOOM NADWATUL ULAMA, LUCKNOW (21-09-2020) 1- DARUL ULOOM TAJUL MASAJID x‰ ZgZ Š 13- MA'HAD ANWARUL ULOOM x‰ ZgZ âZm BHOPAL . PIN: 462 001 (M.P.) w*0ÈÔ.]R `Z *@ NAGINA MASJID, NAWAB PURA Š*!W-8 Zzg Distt: AURANGABAD . PIN: 431 001 (M.H.) 2- JAMIA ISLAMIA, JAMIA AABAD ðsZeY P.O.BOX NO: 10-Town: BHATKA L, gzZg »ÔF 14- DARUT TALEEM WAS SANAT gz» .9 E Distt: KARWAR . PIN: 581 320 (U.KARNATAK) 129-C , JAJMAU , ð0 EY ÔÏ Ô921B ïGš3{ÅzZ ³ ZgZ Š Distt: KANPUR. PIN: 208 010 (U.P. ) 8- 3- JAMIA ISLAMIA KASHIFUL ULOOM JAMA MASJID , BADDI LANE, P.BOX NO: 91 15- MA'AHAD SYEDNA ABI BAKR SIDDIQ ;& Distt: AURANGABAD . PIN: 431 001 (M.H.) Vill: MAHPAT MAU, P.O. KAKORI g~ »Ã Ô¸ïGF3X Distt: LUCKNOW. PIN: 227 107 (U.P.) ~ 4- JAMIA ISLAMIA |Ô /¥W gÔZ 7¡ÔðsZeY P.O. MUZAFFAR PUR (GAMBHIRPUR) 16- MADRASA MAZHARUL ISLAM xsÑZ1 Distt: AZAMGARH . PIN: 276 302 (U.P.) BILLOCH PURA, P.O. RAJENDAR NAGAR Distt: LUCKNOW. PIN: 226 004 (U.P.) ~ 5- DARUL ULOOM NOORUL ISLAM wC{ JALPAPUR, P.O.BOX: NO-1, INARUA BAZAR 17- JAMIA-TUL IMAM WALIULLAH AL- ( Distt: SUNSARI. (NEPAL) g7F5é E7Ò ÔxsÑgZ âx‰ ZgZ Š ISLAMIA, Vill: & P.O. PHULAT 8-Ôô¡ÔïGÒ£F Distt: MUZAFFAR NAGR . PIN: 251 201 U.P 6- JAMIA ISALAMIA ARABIA GULZAR-E- -HUSAINIA,Town: AJRARA FgggZZZgZ111ÔÔÔ²²²ðððsssZZZeeeYYY 18- MADRASA MADINATUL ULOOM (Anjuman) Distt: MEERUT : 245 20 6 (U.P.) J÷I Zh{Ô `Z DEEPA SARAE iÔñZu6ŠÔ³xZ ‰ZîGE0 G"ægæ Distt: SAMBHAL. -

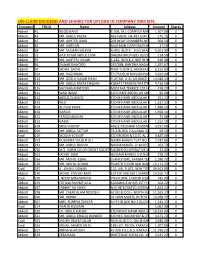

Un-Claim Dividend and Shares for Upload in Company Web Site

UN-CLAIM DIVIDEND AND SHARES FOR UPLOAD IN COMPANY WEB SITE. Company FOLIO Name Address Amount Shares Abbott 41 BILQIS BANO C-306, M.L.COMPLEX MIRZA KHALEEJ1,507.00 BEG ROAD,0 PARSI COLONY KARACHI Abbott 43 MR. ABDUL RAZAK RUFI VIEW, JM-497,FLAT NO-103175.75 JIGGAR MOORADABADI0 ROAD NEAR ALLAMA IQBAL LIBRARY KARACHI-74800 Abbott 47 MR. AKHTER JAMIL 203 INSAF CHAMBERS NEAR PICTURE600.50 HOUSE0 M.A.JINNAH ROAD KARACHI Abbott 62 MR. HAROON RAHEMAN CORPORATION 26 COCHINWALA27.50 0 MARKET KARACHI Abbott 68 MR. SALMAN SALEEM A-450, BLOCK - 3 GULSHAN-E-IQBAL6,503.00 KARACHI.0 Abbott 72 HAJI TAYUB ABDUL LATIF DHEDHI BROTHERS 20/21 GORDHANDAS714.50 MARKET0 KARACHI Abbott 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD616.00 KARACHI0 Abbott 96 ZAINAB DAWOOD 267/268, BANTWA NAGAR LIAQUATABAD1,397.67 KARACHI-190 267/268, BANTWA NAGAR LIAQUATABAD KARACHI-19 Abbott 97 MOHD. SADIQ FIRST FLOOR 2, MADINA MANZIL6,155.83 RAMTLA ROAD0 ARAMBAG KARACHI Abbott 104 MR. RIAZUDDIN 7/173 DELHI MUSLIM HOUSING4,262.00 SOCIETY SHAHEED-E-MILLAT0 OFF SIRAJUDULLAH ROAD KARACHI. Abbott 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE14,040.44 APARTMENT0 PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. Abbott 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND4,716.50 KARACHI-74000.0 Abbott 135 SAYVARA KHATOON MUSTAFA TERRECE 1ST FLOOR BEHIND778.27 TOOSO0 SNACK BAR BAHADURABAD KARACHI. Abbott 141 WASI IMAM C/O HANIF ABDULLAH MOTIWALA95.00 MUSTUFA0 TERRECE IST FLOOR BEHIND UBL BAHUDARABAD BRANCH BAHEDURABAD KARACHI Abbott 142 ABDUL QUDDOS C/O M HANIF ABDULLAH MOTIWALA252.22 MUSTUFA0 TERRECE 1ST FLOOR BEHIND UBL BAHEDURABAD BRANCH BAHDURABAD KARACHI. -

Yunas Khan* Ashfaq Ali**

PAKISTAN–Bi-annual Research Journal Vol. No 56, January- June 2020 ISKANDER MIRZA: A PROFILE Yunas Khan* Ashfaq Ali** Abstract This study aims to descriptively analyze the profile of Iskander Mirza in the light of available information to give a clear picture about the subject matter at hand. Iskander Mirza was a West Bengali politician with rich experience in bureaucracy in British India and witnessed the partition. He was the person who lent support to the cause of the Muslim League and won the confidence of a cantankerous leader like Mr Jinnah in united India. With the passage of time and changing environment, he became a political elite and a power monger. He played havoc with democracy in Pakistan by pulling the military in Politics in Pakistan, particularly General Ayub Khan, who banished democracy for long. The role of Mirza Iskander was simply that of a "lord creator" who played the round of 'find the stowaway' with the popular government of Pakistan in collusion with different lawmakers, which later on destroyed democratic culture in Pakistan perpetually and praetorian rule turned into fait accompli. Mirza detested politicians and democratic governments in Pakistan and instead, preferred military rule in synchronization with civil administration, as the panacea for all the maladies of Pakistan, in order to remain intact in politics and spare his position. Iskander was not only physically overthrown from Pakistan but was permanently banished from the psyches of Pakistanis, too. Despite the fact, Mirza was the guru of Pakistan’s politics he grabbed no academic eye. On dismissal from Presidency Mirza fell from favours and was deported from Pakistan despicably and was not permitted internment.