Petitioners, V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Axos Financial, Inc. Form 8-K Current Event Report Filed 2021-05-05

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM 8-K Current report filing Filing Date: 2021-05-05 | Period of Report: 2021-05-04 SEC Accession No. 0001299709-21-000106 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER Axos Financial, Inc. Mailing Address Business Address 9205 WEST RUSSELL ROAD 9205 WEST RUSSELL ROAD CIK:1299709| IRS No.: 330867444 | State of Incorp.:DE | Fiscal Year End: 0630 SUITE #400 SUITE #400 Type: 8-K | Act: 34 | File No.: 001-37709 | Film No.: 21890447 LAS VEGAS NV 89148 LAS VEGAS NV 89148 SIC: 6035 Savings institution, federally chartered (858) 649-2218 Copyright © 2021 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported): May 4, 2021 Axos Financial, Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 001-37709 33-0867444 (State or other jurisdiction of (IRS Employer Identification incorporation) (Commission File Number) Number) 9205 West Russell Road, STE 400, Las Vegas, NV 89148 (Address of principal executive offices) (zip code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (858) 649-2218 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Trading Symbol(s) Name of each exchange on which registered Common stock, $.01 par value AX New York Stock Exchange Not Applicable (Former name or former address, if changed since last report.) Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions (see General Instruction A.2. -

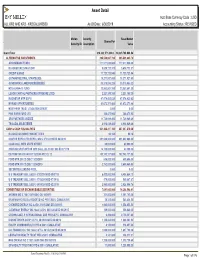

Asset Detail Acct Base Currency Code : USD ALL KR2 and KR3 - KR2GALLKRS00 As of Date : 6/30/2019 Accounting Status : REVISED

Asset Detail Acct Base Currency Code : USD ALL KR2 AND KR3 - KR2GALLKRS00 As Of Date : 6/30/2019 Accounting Status : REVISED Mellon Security Base Market . Shares/Par Security ID Description Value Grand Total 214,322,571,803.0.. 18,225,768,088.54 ALTERNATIVE INVESTMENTS 395,539,667.780 395,539,665.78 ARROWMARK FUND I 177,577,920.000 177,577,920.00 BLACKSTONE STRAT OPP 5,629,722.370 5,629,722.37 CREDIT SUISSE 11,723,723.940 11,723,723.94 GOTHAM NEUTRAL STRATEGIES 18,271,927.600 18,271,927.60 GOVERNORS LANE FUNDÉÉÉÉÉÉÉÉ 30,370,085.220 30,370,085.22 H2O ALPHA-10 FUND 23,983,801.350 23,983,801.35 LUXOR CAPITAL PARTNERS OFFSHORE LTDD 2,221,195.350 2,221,195.35 MAGNETAR MTP EOF II 47,074,425.620 47,074,425.62 MYRIAD OPPORTUNITIES 61,672,371.480 61,672,371.48 NORTHERN TRUST LITIGATION CREDIT 2.000 0.00 PINE RIVER FUND LTD 366,473.900 366,473.90 SRS PARTNERS USÉÉÉÉ 11,729,989.490 11,729,989.49 TRICADIA SELECTÉÉÉÉ 4,918,029.460 4,918,029.46 CASH & CASH EQUIVALENTS 901,268,217.160 887,047,810.08 BLACKROCK MONEY MARKET FD B 90.160 90.16 CANTOR REPO A TRI REPO 2.450% 07/01/2019 DD 06/28/19 691,600,000.000 691,600,000.00 CASH COLL WITH STATE STREET 60,000.000 60,000.00 CNH/USD SPOT OPTION 2019 CALL JUL 19 007.000 ED 071119 14,130,000.000 42,390.00 EB TEMP IVN FD VAR RT 12/31/49 FEE CL 12 182,143,127.000 182,143,127.00 FORD MTR CR CO DISC 11/25/2019 636,000.000 609,606.00 FORD MTR CR CO DISC 12/04/2019 2,762,000.000 2,685,469.58 SECURITIES LENDING POOL 0.000 0.00 U S TREASURY BILL 0.000% 07/02/2019 DD 05/07/19 6,422,000.000 6,408,684.73 U S TREASURY -

Concorde Securities Ltd. Hereby Certifies This to Be a True Copy of the Original

Concorde Securities Ltd. hereby certifies this to be a true copy of the original. ________________________ Zsuzsanna Kovács Chief Accountant Concorde Securities Ltd. Concorde Securities Ltd. Annual Report and Independent Auditor’s Report 31 December 2018 Deloitte Auditing and Consulting Ltd. H-1068 Budapest, Dózsa György út 84/C, Hungary Postal address: H-1438 Budapest, Pf. 471 Phone:+36 (1) 428-6800 Fax: +36 (1) 428-6801 www.deloitte.hu Incorporated: Company Registry Court of Budapest-Capital Regional Court Company registration number: 01- 09-071057 INDEPENDENT AUDITOR’S REPORT For the shareholders of Concorde Securities Ltd. Opinion We have audited the annual report of Concorde Securities Ltd. (hereinafter: the ‘Company’) for the year 2018, which comprise the balance sheet as at 31 December 2018—showing total assets and liabilities of HUF 60,556,394 thousand and profit after taxes of HUF 1,015,984 thousand—, income statement for the same period as well as notes to the annual report including a summary of significant accounting policies. In our opinion, the annual report provides a true and fair view of the financial position of the Company as at 31 December 2018 and of its financial performance for the business year then ended, in accordance with Act C of 2000 on Accounting (hereinafter: Accounting Act) effective in Hungary. Basis for the Opinion We conducted our audit in accordance with the Hungarian National Standards on Auditing and the effective Hungarian laws and other regulations regarding audits. Our responsibilities under these standards are described in more detail in ‘The auditor’s responsibility for the audit of the annual report’ section of our report. -

Axos Financial, Inc. Form 8-K Current Event Report Filed 2018-10-01

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM 8-K Current report filing Filing Date: 2018-10-01 | Period of Report: 2018-09-28 SEC Accession No. 0001299709-18-000122 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER Axos Financial, Inc. Mailing Address Business Address 4350 LA JOLLA VILLAGE DR. 4350 LA JOLLA VILLAGE DR. CIK:1299709| IRS No.: 330867444 | State of Incorp.:DE | Fiscal Year End: 0630 SUITE #140 MAILSTOP 801 SUITE #140 MAILSTOP 801 Type: 8-K | Act: 34 | File No.: 001-37709 | Film No.: 181095958 SAN DIEGO CA 92122 SAN DIEGO CA 92122 SIC: 6035 Savings institution, federally chartered (858) 350-6200 Copyright © 2018 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported): September 28, 2018 AXOS FINANCIAL, INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 000-51201 33-0867444 (State or other jurisdiction of (IRS Employer Identification incorporation) (Commission File Number) Number) 4350 La Jolla Village Drive, Suite 140, San Diego, CA 92122 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (858) 350-6200 Not Applicable (Former name or former address, if changed since last report.) Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant -

Axos Financial, Inc. 2019 Annual Report

AXOS FINANCIAL,AXOS INC FINANCIAL,AXOS INC 92059205 WestWest RussellRussell RoadRoad SuiteSuite 400400 LasLas Vegas,Vegas, NVNV 8914889148 . 2019 ANNUAL REPORT . 2019 ANNUAL REPORT . 2019 www.axosfinancial.comwww.axosfinancial.com AXOS FINANCIAL, INC. 2019 ANNUAL REPORT EXECUTIVE OFFICERS BOARD OF DIRECTORS Gregory Garrabrants Paul J. Grinberg AXOS OFFICE LOCATIONS President and Chairman Chief Executive Officer Nicholas A. Mosich Eshel Bar-Adon Vice Chairman Executive Vice President James S. Argalas Specialty Finance and J. Brandon Black Chief Legal Officer Tamara Bohlig Jill Bauer James J. Court Executive Vice President Uzair Dada Trustee and Fiduciary Services Gregory Garrabrants Mary Ellen Ciafardini Edward J. Ratinoff Executive Vice President Human Resources CORPORATE HEADQUARTERS Thomas Constantine Axos Financial, Inc. Executive Vice President 9205 West Russell Road Chief Credit Officer Suite 400 Las Vegas, NV 89148 New York, NY* Jan Durrans Omaha, NE www.axosfinancial.com (Axos Clearing) Executive Vice President Salt Lake City, UT Chief of Staff and INVESTOR RELATIONS Columbus, OH Chief Performance Officer Kansas City, KS* Johnny Lai James Fraser Vice President, Corporate Development Los Angeles, CA* Las Vegas, NV Executive Vice President and Investor Relations Orange County, CA* Specialty Real Estate, C&I Lending (858) 649-2218 [email protected] San Diego, CA Raymond Matsumoto Executive Vice President CORPORATE SECRETARY Chief Operating Officer Angela Lopez Andrew J. Micheletti Corporate Secretary, Executive Vice President -

Cavanal Hill Funds Form NPORT-P Filed 2021-01-25

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM NPORT-P Filing Date: 2021-01-25 | Period of Report: 2020-11-30 SEC Accession No. 0001752724-21-010231 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER Cavanal Hill Funds Mailing Address Business Address 4400 EASTON COMMONS 4400 EASTON COMMONS CIK:864508| IRS No.: 000000000 | State of Incorp.:OH #200 #200 Type: NPORT-P | Act: 40 | File No.: 811-06114 | Film No.: 21549553 COLUMBUS OH 43219 COLUMBUS OH 43219 800-762-7085 Copyright © 2021 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document CAVANAL HILL FUNDS Limited Duration Fund Schedule of Portfolio Investments November 30, 2020 (Unaudited) Shares or Principal Security Description Value Amount Asset Backed Securities (18.2%) $ 1,143,192 Asset Backed Securities Corp. Home Equity Loan Trust, Series 2006-HE1, Class A4, 0.75% (US0001M + 30 bps), $ 1,131,168 1/25/36, Callable 12/25/20 @ 100* 1,377,093 Bayview Financial Mortgage Pass-Through Trust, Series 2005-C, Class M3, 1.13% (US0001M + 65 bps), 6/28/44, 1,373,464 Callable 12/28/20 @ 100* 460,038 Cazenovia Creek Funding II LLC, Series 2018-1A, Class A, 3.56%, 7/15/30(a) 461,927 1,296,220 CDC Mortgage Capital Trust, Series 2002-HE1, Class A, 0.77% (US0001M + 62 bps), 1/25/33, Callable 12/25/20 @ 1,284,744 100* 1,503,541 CIT Mortgage Loan Trust, Series 2007-1, Class 1A, 1.50% (US0001M + 135 bps), 10/25/37, Callable 6/25/25 @ 1,509,496 100*(b) 586 Citigroup Mortgage Loan Trust, Inc., Series 2005-WF1, Class A5, 5.01%, 11/25/34, Callable 12/25/20 @ 100*(c) 588 241 -

Bofi Holding, Inc. Form 8-K Current Event Report Filed 2018-09-12

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM 8-K Current report filing Filing Date: 2018-09-12 | Period of Report: 2018-09-11 SEC Accession No. 0001299709-18-000113 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER BofI Holding, Inc. Mailing Address Business Address 4350 LA JOLLA VILLAGE DR. 4350 LA JOLLA VILLAGE DR. CIK:1299709| IRS No.: 330867444 | State of Incorp.:DE | Fiscal Year End: 0630 SUITE #140 MAILSTOP 801 SUITE #140 MAILSTOP 801 Type: 8-K | Act: 34 | File No.: 001-37709 | Film No.: 181065964 SAN DIEGO CA 92122 SAN DIEGO CA 92122 SIC: 6035 Savings institution, federally chartered (858) 350-6200 Copyright © 2018 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported): September 11, 2018 AXOS FINANCIAL, INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 000-51201 33-0867444 (State or other jurisdiction of (IRS Employer Identification incorporation) (Commission File Number) Number) 4350 La Jolla Village Drive, Suite 140, San Diego, CA 92122 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (858) 350-6200 BofI Holding, Inc. (Former name or former address, if changed since last report.) Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions (see General Instruction A.2. -

Axos Financial Annual Report 2020

Axos Financial Annual Report 2020 Form 10-K (NYSE:AX) Published: August 26th, 2020 PDF generated by stocklight.com UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 __________________________________________________________________________________________ FORM 10-K ☒ ANNUAL REPORT UNDER SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended June 30, 2020 ☐ TRANSITION REPORT UNDER SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission file number: 001-37709 __________________________________________________________________________________________ AXOS FINANCIAL, INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 33-0867444 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 9205 West Russell Road, STE 400, Las Vegas, NV 89148 (Address of principal executive offices) (zip code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (858) 649-2218 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Trading Symbol(s) Name of each exchange on which registered Common stock, $.01 par value AX New York Stock Exchange 6.25% Subordinated Notes Due 2026 AXO New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None __________________________________________________________________________________________ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes o No ☒ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant: (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports); and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Third Quarter Report

APRIL 30, 2021 2021 Quarterly Report (Unaudited) iShares U.S. ETF Trust Table of Contents Page iShares Evolved U.S. Consumer Staples ETF . ............................................................................................................................ 3 iShares Evolved U.S. Discretionary Spending ETF . ......................................................................................................................... 6 iShares Evolved U.S. Financials ETF ....................................................................................................................................... 10 iShares Evolved U.S. Healthcare Staples ETF .............................................................................................................................. 14 iShares Evolved U.S. Innovative Healthcare ETF ............................................................................................................................ 17 iShares Evolved U.S. Media and Entertainment ETF ........................................................................................................................ 21 iShares Evolved U.S. Technology ETF ...................................................................................................................................... 23 2 Schedule of Investments (unaudited) iShares Evolved U.S. Consumer Staples ETF April 30, 2021 (Percentages shown are based on Net Assets) SecurityShares Value SecurityShares Value Common Stocks Food (continued) Calavo Growers Inc. ....................................... -

2021-Proxy.Pdf

Client: LendingClub Corporation Date: 04/20/2021 3:17 PM Trim Size: 8.5" x 11" Project: 2021 Proxy Statement Version: 9 Color: CMYK Job Number: 21-155 Page 1 of 77 Revisions: Clean UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 SCHEDULE 14A Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Filed by the Registrant Filed by a Party other than the Registrant Check the appropriate box: Preliminary Proxy Statement Confidential, for Use of the Commission Only (as permitted by Rule 14a-6(e)(2)) Definitive Proxy Statement Definitive Additional Materials Soliciting Material under §240.14a-12 LendingClub Corporation (Name of Registrant as Specified in Its Charter) Payment of Filing Fee (Check the appropriate box): No fee required. Fee computed on table below per Exchange Act Rules 14a-6(i)(1) and 0-11. 1) Title of each class of securities to which transaction applies: 2) Aggregate number of securities to which transaction applies: 3) Per unit price or other underlying value of transaction computed pursuant to Exchange Act Rule 0-11 (set forth the amount on which the filing fee is calculated and state how it was determined): 4) Proposed maximum aggregate value of transaction: 5) Total fee paid: Fee paid previously with preliminary materials. Check box if any part of the fee is offset as provided by Exchange Act Rule 0-11(a)(2) and identify the filing for which the offsetting fee was paid previously. Identify the previous filing by registration statement number, or the Form or Schedule and the date of its filing. -

CRA Evaluation Charter No. 716456

PUBLIC DISCLOSURE March 4, 2019 COMMUNITY REINVESTMENT ACT PERFORMANCE EVALUATION Axos Bank Charter Number: 716456 4350 La Jolla Village Drive, Suite 140 San Diego, CA 92122 Office of the Comptroller of the Currency 1551 North Tustin Ave., Suite 1050 Santa Ana, CA 92705 NOTE: This document is an evaluation of this institution's record of meeting the credit needs of its entire community, including low- and moderate-income neighborhoods, consistent with safe and sound operation of the institution. This evaluation is not, and should not be construed as, an assessment of the financial condition of this institution. The rating assigned to this institution does not represent an analysis, conclusion, or opinion of the federal financial supervisory agency concerning the safety and soundness of this financial institution. Charter Number: 716456 Table of Contents OVERALL CRA RATING ....................................................................................................................... 2 DEFINITIONS AND COMMON ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................... 3 DESCRIPTION OF INSTITUTION ........................................................................................................ 7 SCOPE OF THE EVALUATION ............................................................................................................ 9 DISCRIMINATORY OR OTHER ILLEGAL CREDIT PRACTICES REVIEW .............................. 11 STATE RATING .................................................................................................................................... -

Vanguard Russell 2000 Index Funds Annual Report August 31, 2020

Annual Report | August 31, 2020 Vanguard Russell 2000 Index Funds Vanguard Russell 2000 Index Fund Vanguard Russell 2000 Value Index Fund Vanguard Russell 2000 Growth Index Fund See the inside front cover for important information about access to your fund’s annual and semiannual shareholder reports. Important information about access to shareholder reports Beginning on January 1, 2021, as permitted by regulations adopted by the Securities and Exchange Commission, paper copies of your fund’s annual and semiannual shareholder reports will no longer be sent to you by mail, unless you specifically request them. Instead, you will be notified by mail each time a report is posted on the website and will be provided with a link to access the report. If you have already elected to receive shareholder reports electronically, you will not be affected by this change and do not need to take any action. You may elect to receive shareholder reports and other communications from the fund electronically by contacting your financial intermediary (such as a broker-dealer or bank) or, if you invest directly with the fund, by calling Vanguard at one of the phone numbers on the back cover of this report or by logging on to vanguard.com. You may elect to receive paper copies of all future shareholder reports free of charge. If you invest through a financial intermediary, you can contact the intermediary to request that you continue to receive paper copies. If you invest directly with the fund, you can call Vanguard at one of the phone numbers on the back cover of this report or log on to vanguard.com.