What's Happened to the "Free" in Floor Exercise? Page 1 of 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AGE GROUP DEVELOPMENT and COMPETITION PROGRAM

FÉDÉRATION INTERNATIONALE DE GYMNASTIQUE Fondée en 1881 AGE GROUP DEVELOPMENT and COMPETITION PROGRAM for Women’s Artistic Gymnastics Principal Authors H a r d y F I N K Lilia ORTIZ LÓPEZ Dieter HOFMANN E d i t i o n 1 - 2 0 2 1 AVENUE DE LA GARE 12A, CASE POSTALE 630, 1001 LAUSANNE, SWITZERLAND TÉL. (+41) 21 321 55 10 – FAX (+41) 21 321 55 19 www.gymnastics.sport – [email protected] Page 2 de 127 Table of Contents 1 Acknowledgements Page 4 2 Overview and Philosophy of FIG Age Group Development Program Page 5 3 Overview of Long-Term Gymnast Development Page 9 4 Competition Program – Compulsory Exercises and Optional Rules Page 15 5 Compulsory Exercises Page 33 6 Physical and Technical Ability Testing Program Page 83 7 Music & Rhythm & Ballet Development and Testing Program Page 111 8 Skill Acquisition Profiles Page 121 Where there is a difference among the languages, the English text shall be considered correct. Copyright Fédération Internationale de Gymnastique (FIG) – 2015 Avenue de la Gare 12A, 1003 Lausanne, Switzerland Tf: +41 21 321 55 10 – Fx: +41 21 321 55 19 – [email protected] Page 3 de 127 Acknowledgements Many persons have contributed to the full content, development and preparation of this FIG Age Group Program. The project was initiated and encouraged by FIG President, Prof. Bruno GRANDI to serve as an effective program for the safe and systematic long-term development of gymnasts. The development and implementation of this FIG Age Group Program is partially funded by the International Olympic Committee (IOC). -

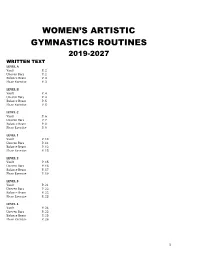

Women's Artistic Gymnastics Routines

WOMEN’S ARTISTIC GYMNASTICS ROUTINES 2019-2027 WRITTEN TEXT LEVEL A Vault P. 2 Uneven Bars P. 2 Balance Beam P. 3 Floor Exercise P. 3 LEVEL B Vault P. 4 Uneven Bars P. 4 Balance Beam P. 5 Floor Exercise P. 5 LEVEL C Vault P. 6 Uneven Bars P. 7 Balance Beam P. 8 Floor Exercise P. 9 LEVEL 1 Vault P. 10 Uneven Bars P. 11 Balance Beam P. 12 Floor Exercise P. 13 LEVEL 2 Vault P. 15 Uneven Bars P. 16 Balance Beam P. 17 Floor Exercise P. 19 LEVEL 3 Vault P. 21 Uneven Bars P. 22 Balance Beam P. 22 Floor Exercise P. 23 LEVEL 4 Vault P. 24 Uneven Bars P. 25 Balance Beam P. 25 Floor Exercise P. 26 1 LEVEL A VAULT (Level A) The video is the official version. This written text is merely an additional teaching tool. * Spotter required May be performed in a wheelchair or with a walker (or other assistance) Value Element 2.0 Salute to judge 2.0 Move to a designated point 2.0 “Stick” landing 2.0 Salute to judge Difficulty 8.0 Execution 2.0 Max. score 10.0 UNEVEN BARS (Level A) The video is the official version of the routine. This written text is merely an additional teaching tool. * Spotter required Performed seated, either with a hand held single bar or the low bar of the uneven bars Value Element 1.0 Salute at beginning of the routine 2.0 Grasp the bar in an overgrip (either simultaneously or one hand at a time) 1.0 Change 1 hand to an undergrip. -

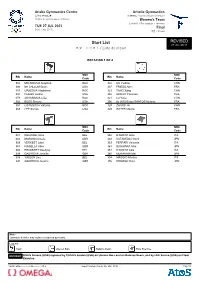

Start List REVISED 27 JUL 20:41 スタートリスト / Liste De Départ

Ariake Gymnastics Centre Artistic Gymnastics 有明体操競技場 体操競技 / Gymnastique artistique Centre de gymnastique d'Ariake Women's Team 女子団体 / Par équipes - femmes TUE 27 JUL 2021 Final Start Time 19:45 決勝 / Finale Start List REVISED 27 JUL 20:41 スタートリスト / Liste de départ ROTATION 1 OF 4 NOC NOC Bib Name Bib Name Code Code 382 MELNIKOVA Angelina ROC 322 OU Yushan CHN 396 Mc CALLUM Grace USA 337 FRIESS Aline FRA 383 URAZOVA Vladislava ROC 323 TANG Xijing CHN 394 CHILES Jordan USA 338 HEDUIT Carolann FRA 378 AKHAIMOVA Liliia ROC 321 LU Yufei CHN 392 BILES Simone USA 336 de JESUS dos SANTOS Melanie FRA 381 LISTUNOVA Viktoriia ROC 324 ZHANG Jin CHN 395 LEE Sunisa USA 335 BOYER Marine FRA NOC NOC Bib Name Bib Name Code Code 307 DERWAEL Nina BEL 352 D'AMATO Alice ITA 342 MORGAN Amelie GBR 358 HATAKEDA Hitomi JPN 309 VERKEST Jutta BEL 353 FERRARI Vanessa ITA 341 KINSELLA Alice GBR 361 SUGIHARA Aiko JPN 306 BRASSART Maellyse BEL 351 D'AMATO Asia ITA 339 GADIROVA Jennifer GBR 360 MURAKAMI Mai JPN 308 VAELEN Lisa BEL 354 MAGGIO Martina ITA 340 GADIROVA Jessica GBR 359 HIRAIWA Yuna JPN Note: Gymnasts in Italics may replace competing gymnasts. Legend: Vault Uneven Bars Balance Beam Floor Exercise REVISED BILES Simone (USA) replaced by CHILES Jordan (USA) on Uneven Bars and on Balance Beam, and by LEE Sunisa (USA) on Floor Exercise. GARWTEAM--------------FNL---------_51D 2 Report Created TUE 27 JUL 2021 20:41 Page 1/4 Ariake Gymnastics Centre Artistic Gymnastics 有明体操競技場 体操競技 / Gymnastique artistique Centre de gymnastique d'Ariake Women's Team 女子団体 / Par équipes -

Report of the Independent Investigation

Report of the Independent Investigation The Constellation of Factors Underlying Larry Nassar’s Abuse of Athletes Joan McPhee | James P. Dowden December 10, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................1 INVESTIGATIVE INDEPENDENCE, SCOPE AND METHODOLOGY .................................12 A. Independence .........................................................................................................13 B. Scope ......................................................................................................................14 C. Methodology ..........................................................................................................14 1. Witness Interviews .....................................................................................16 2. Document Review ......................................................................................17 I. WHAT HAPPENED ..........................................................................................................19 A. Nassar’s Abuse.......................................................................................................20 B. Efforts to Bring Nassar to Justice ..........................................................................24 C. Legal Proceedings ..................................................................................................30 1. Criminal Proceedings .................................................................................30 -

Gymnastics Games

This -or- That Gymnastics Edition Circle or highlight the one in each row that you like better BARS BEAM PRACTICE MEETS GRIPS NO GRIPS VAULT FLOOR SIMONE BILES GABBY DOUGLAS STICK IT FULL OUT NCAA OLYMPICS COMPULSORIES OPTIONALS HAIR TIES HEADBANDS SPARKLY LEO PLAIN LEO DOUBLE BACK DOUBLE FULL DONUTS ICE CREAM WEAR SHORTS OVER WEAR ONLY LEO LEO TO PRACTICE TO PRACTICE what's in your gymnastics bag? Circle the things that are in your gym bag m fate... Event: Skill to do: Skill to watch: Gymnast: Gymnastics Movie: Leotard I own: GYMNASTICS BINGO To Play Gymnastics Bingo: 1.Cut out the pictures from the Answer Key on the next page and put them in a hat or bowl. 2.Give every Bingo player her own card (there are 8 different versions for up to 8 players). 3. (Optional) If you don't have Bingo markers, print out the Gymnastics Bingo Markers page for each player and have her cut out the squares. She will use these to cover the squares on her Bingo board as each picture is called. For best results, print the Bingo cards and Bingo markers on heavyweight paper. Have fun! Be sure to tag us on Instagram @gymnasticshq if you play! GYMNASTICS BINGO Cut out each of these pictures and place them in a hat or bowl to randomly pick from. Answer Key GYMNASTICS BINGO MARKERS Optional: If you don't have Bingo markers at home you can use these instead. Each player would get her own sheet to cut out and use. GYMNASTICS BINGO FREE SPACE GYMNASTICS BINGO FREE SPACE GYMNASTICS BINGO FREE SPACE GYMNASTICS BINGO FREE SPACE GYMNASTICS BINGO FREE SPACE GYMNASTICS BINGO FREE SPACE GYMNASTICS BINGO FREE SPACE GYMNASTICS BINGO FREE SPACE. -

2017 – 2020 CODE of POINTS Women's Artistic Gymnastics

FÉDÉRATION INTERNATIONALE DE GYMNASTIQUE 2017 – 2020 CODE OF POINTS Women’s Artistic Gymnastics Approved by the FIG Executive Committee For Women’s Artistic Gymnastics competitions at Olympic Games Youth Olympic Games World Championships Regional and Intercontinental Competitions Events with international participants In competitions for nations with lower level of gymnastics development, as well as for Junior Competitions, modified competition rules should be appropriately designed by continental or regional technical authorities, as indicated by the age and level of development (see the FIG Age Group Development Program) The Code of Points is the property of the FIG. Translation and copying are prohibited without prior written approval by FIG. In case any statement contained herein is in conflict with the Technical Regulations, the Technical Regulations shall take precedence. Where there is a difference among the languages, the English text shall be considered correct. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS FIG CODE UPDATES President Nellie Kim BLR After the Official FIG Competitions the FIG/WTC publishes a WAG 1st Vice-President Donatella Sacchi ITA Newsletter which includes: 2nd Vice-President Naomi Valenzo MEX – all new elements and variations with a number and illustration Secretary Kym Dowdell AUS – new connections Member Qiurui Zhou CHN Member Yoshie Harinishi JPN The Code Update will be sent by the FIG Secretary General to all affiliated Member Loubov Burda-Andrianova RUS federations, including the effective date, from which time it is valid for all Athlete representative Beth Tweddle GBR further FIG competitions. James Stephenson & USA Illustrations Koichi Endo JPN Original illustrations Ingrid Nicklaus GER HELP DESK Original Symbols Margot Dietz GER For additional examples, descriptions, definitions, updates and clarifications can be found at the FIG website under WAG Help Desk. -

2021 CGA Awards Program

2021 College Gymnastics Association Awards Program CGA AWARDS PROGRAM 2021 1 Statement from CGA President Mike Burns Last year at this time we were just at the start of a year that some would prefer to forget altogether. We lost the last part of our season which was devastating to us all. No conference and national champions were crowned, no All-Americans were determined, no epic battles were fought on the competition floor. And that was a bitter pill to swallow. Every one of us was impacted in a negative way. Something we always expected to happen was taken away and that started the process of self reflection and trying to manage the tidal wave of emotions that washed over us all. It was a time we'd all like to forget indeed. However, if we decided to forget this crazy year, think about all of the awesome things we'd be purging from our memories. All the Zoom meetings with our teams that helped strengthen the bonds within our teams; all the ways you found to stay in shape; all the injuries that actually had a chance to heal a little further; all the positive energy you were forced to find in the face of adversity to just find a way. Adversity is an interesting thing. At first it seems impenetrable, a problem without a solution. But then, what happens? Our collective creative juices start to flow and solutions are discovered. We enter the 'Lewis & Clark' phase of discovery. We drive into unknown territory and while it seems daunting at first, lo and behold, we adjust to a new way of thinking and acting that never would have occurred if not for the original adversity we encountered. -

2010-2011 Missouri Gymnastics

2010-2011 Missouri Gymnastics MISSOURI INFORMATION Beauty and the Beast History 5th Annual Last year’s Beauty and the Beast meet saw the Tigers Location ..................................................Columbia, Mo. Beauty and the Beast hosting New Hampshire, while wrestling matched up Founded .................................................................. 1839 vs. against Oklahoma. The Tigers came out on top with a Enrollment ........................................................... 31,314 195.125-192.975 victory. Shire earned her third all-around Nickname ..............................................................Tigers Southeast Missouri State Colors ..............................................Old Gold and Black Saturday, Jan. 15, 2011 title of the season, the 16th of her career, and Mary Burke Chancellor ...................................... Dr. Brady S. Deaton 2 p.m. took the bars title while finishing second in the all-around. Athletic Director ..................................... Michael Alden Lauren Swankoski took the third place spot. SWA ...................................................... Sarah Reesman Hearnes Center; Columbia, Mo. Conference ........................................................... Big 12 Last Time vs. SEMO Affiliation ...........................................NCAA Division I Missouri traveled to Cape Girardeu last season to face the Home Arena ........................................... Hearnes Center Redhawks and the Alaska-Anchorage Seawolves. The Capacity .............................................................. -

Olympic GYMNASTICS

Olympic Greats pic olym GYMNASTICS LEGENDS MARTIN GITLIN ThisBolt is World published Book by Blackedition Rabbit of WorldBooks Soccer Records isP.O. published Box 3263, byMankato, agreement Minnesota, between 56002. www.blackrabbitbooks.com CopyrightBlack Rabbit © 2021 Books Black Rabbitand World Books Book, Inc. © 2018 Black Rabbit Books, 2140Jen Besel, Howard editor; Dr. Catherine West, Cates, designer; Omay Ayres, photo researcher North Mankato, MN 56003 U.S.A. WorldAll rights Book, reserved. Inc., No part of this book may be reproduced, 180stored North in a retrieval LaSalle system St., Suite or transmitted 900, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission fromChicago, the publisher. IL 60601 U.S.A. AllLibrary rights of Congress reserved. Cataloging-in-Publication No part of this book Data may be reproduced in any Names: Gitlin, Marty, author. Title:form Olympic without gymnastics written permission legends / by fromMartin theGitlin. publisher. Other titles: Bolt (North Mankato, Minn.) MarysaDescription: Storm, Mankato, editor; Minnesota Michael : Bolt Sellner, is published designer; by Black Omay Rabbit Ayres, Books, photo2021. | Series: researcher Bolt. Olympic greats | Audience: Ages: 8-12 years. | EN Audience: Grades: 4-6. Identifiers: LCCN 2019027607 (print) | ISBN 9781623102661 NT T (Hardcover) | ISBN 9781644663622 (Paperback) | ISBN 9781623103606 (eBook) O S LibrarySubjects: ofLCSH: Congress Gymnasts—Juvenile Control Number: literature. 2016049979 | Gymnastics—Records. | C Olympics—Juvenile literature. Classification: LCC GV461.3 .G58 2021 (print) | LCC GV461.3 (ebook) | DDCISBN: 796.44—dc23 978-0-7166-9346-8 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019027607 CHAPTER 1 PrintedLC ebook in record the Unitedavailable States at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019027608 at CG Book Printers, PrintedNorth Mankato,in Malaysia. -

Level 8 Regionals Rotation Schedule

Page: 1 Level 8 Regionals Printed: 3/28/2017 11:06:30 A M Rotation Schedule Apr 21-23, 2017 Session: 1 -- Junior A Friday, April 21, 2017 Open Warmup 8:00 AM Timed Warmup 8:35 AM March In 8:20 AM Awards 11:45 AM Flight: A Squad A Adrenaline, HGA, Jenks Gymnastics, Love Gymnastics Squad B Aspire, Bcga, EGA, Pearland Elite Squad C Dynamo, WOGA Gymnastics Squad D 5280, Gold Cup Num Gymnasts: 27 Squad: A 6 Squad: B 7 Vault 134 8 Chloe Womeldorph Love Gymnastics Bars 124 8 Piper Seltmann EGA Bars 126 8 Camryn Richardson HGA 136 8 Nina Laurito Pearland Elite Beam 110 8 Sarah Horne Adrenaline Beam 112 8 Amy Doyle Aspire Floor 132 8 Olivia Cupp Jenks Gymnastics 113 8 Maggie Ball Bcga 133 8 Jaylyn Pomager Love Gymnastics Floor 114 8 Parker Cobb Bcga 109 8 Claire Coddington Adrenaline 115 8 Allisondra Pope Bcga Vault 116 8 Addisyn Snow Bcga Squad: C 7 Squad: D 7 Beam 146 8 Baylie Belman WOGA Gymnastics Floor 105 8 Analiah Solorio 5280 147 8 Alyson Chu WOGA Gymnastics 102 8 Isabella Gee 5280 Floor 123 8 Haley Mustari Dynamo Vault 103 8 Haley Pieroni 5280 151 8 Alexa (Lexi) Weis WOGA Gymnastics 125 8 Samantha O' Gorman Gold Cup Vault 150 8 Ashlee Sullivan WOGA Gymnastics Bars 106 8 Samantha Streeter 5280 148 8 Mallory Johnson WOGA Gymnastics 104 8 Kristina Shchennikova 5280 Bars 149 8 Avery King WOGA Gymnastics Beam 101 8 Jordan Blankenship 5280 ProScore v 5.4.1 - C opy right 1993-2016 A uburn Electronics Group - Licensed to: Premier Gy mnastics - C O Page: 2 Level 8 Regionals Printed: 3/28/2017 11:06:30 A M Rotation Schedule Apr 21-23, 2017 Session: -

The Ukrainian Weekly, 2017

ХРИСТОС НАРОДИВСЯ! CHRIST IS BORN! THEPublished U by theKRAINIAN Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profitW associationEEKLY Vol. LXXXV No. 52-53 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, DECEMBER 24-31, 2017 $2.00 U.S. special envoy says 2017 was deadliest year in Ukraine conflict Anti-government protests end in violence and warns of spiking violence Donbas war RFE/RL heats up The U.S. special envoy for the Ukraine con- flict has said 2017 was the deadliest year in the by Mark Raczkiewycz region since the outbreak of violence three KYIV – Tensions between Ukrainian years ago, and warned that hostilities are again politician Mikheil Saakashvili and erst- ratcheting up. while ally Ukrainian President Petro Kurt Volker’s comments on December 19 Poroshenko were further strained after came as international monitors reported the former Georgian leader called on the intense shelling overnight near the town of president to resign in an open letter he Novoluhanske, part of the eastern Ukrainian published on his Facebook page on region known as the Donbas. December 19. United Nations officials reported eight civil- “Admit to yourself and the nation that ians injured and dozens of homes damaged, you and your associates aren’t capable with winter temperatures complicating mat- of and don’t wish to change Ukraine for ters. the better,” he wrote his former universi- “A lot of people think that this has somehow ty friend. “Your voluntary resignation is Defense Ministry of Ukraine turned into a sleepy, frozen conflict and it’s sta- one of the last chances to quell the polit- Russian shelling from occupied Horlivka damaged a kindergarten in ble and now we have.. -

Returning Biles Helps Carey 'Kill' the Floor After Olympic Flop

Established 1961 13 Sports Tuesday, August 3, 2021 Returning Biles helps Carey ‘kill’ the floor after Olympic flop TOKYO: American Jade Carey singled kill floor’, and that’s what I did.” tears, said: “I have been doing gym- out Simone Biles’ role in helping her to Carey, who succeeds Biles as nastics for over 20 years, so I have a sweep her rivals off the floor for Olympic champion, spoke of her pride lot of emotions.” Olympic gold yesterday, 24 hours after at putting the vault nightmare behind The third gold medal on offer was trailing in a tearful last on the vault. As her to produce “probably the best floor claimed by South Korea’s Shin Jea- the second night of gymnastics appara- routine I’ve ever done in my life”. There hwan, who won the men’s vault on a tus finals got under way in Tokyo, con- was a rare dead-heat for bronze tiebreak from Russian Denis Abliazin. firmation filtered through that Biles will between Japan’s Mai Murakami and The pair both ended with 14.783 points, return to the Olympic arena for today’s Angelina Melnikova, who led the Shin taking the title after outscoring closing beam final. Russians to team gold last week. Abliazin on both his two jumps. “It feels Ahead of her eagerly awaited come- like I am dreaming, it doesn’t feel like back she was at the Ariake Gymnastics Ring-master Liu it’s real. I prepared for this competition Centre to cheer on Carey, the 21-year- Carey’s heroics on the floor were fol- for a long time,” said Shin.