Michael Lewis the Blind Side More Praise for the BLIND SIDE “Yet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brian Mccrea Brmccrea@Ufl

IDH 2930 Section 1D18 HNR Read Moneyball Tuesday 3 (9:35-10:25 a. m.) Little Hall 0117 Brian McCrea brmccrea@ufl. edu (352) 478-9687 Moneyball includes twelve chapters, an epilogue, and a (for me) important postscript. We will read and discuss one chapter a week, then finish with a week devoted to the epilogue and to the postscript. At our first meeting we will introduce ourselves to each other and figure out who amongst us are baseball fans, who not. (One need not have an interest in baseball to enjoy Lewis or to enjoy Moneyball; indeed, the course benefits greatly from disinterested business and math majors.) I will ask you to write informally every class session about the reading. I will not grade your responses, but I will keep a word count. At the end of the semester, we will have an Awards Ceremony for our most prolific writers. While this is not a prerequisite, I hope that everyone has looked at Moneyball the movie (starring Brad Pitt as Billy Beane) before we begin to work with the book. Moneyball first was published—to great acclaim—in 2003. So the book is fifteen-year’s old, and the “new” method of evaluating baseball players pioneered by Billy Beane has been widely adopted. Beane’s Oakland A’s no longer are as successful as they were in the early 2000s. What Lewis refers to as “sabremetrics”—the statistical analysis of baseball performance—has expanded greatly. Baseball now has statistics totally different from those in place as Lewis wrote: WAR (Wins against replacement), WHIP (Walks and hits per inning pitched) among them. -

Baltimore Ravens Press Release Under Armour Performance Center 1 Winning Drive Owings Mills, Md 21117 Ph: 410-701-4000 Baltimoreravens.Com Twitter: @Ravens

BALTIMORE RAVENS PRESS RELEASE UNDER ARMOUR PERFORMANCE CENTER 1 WINNING DRIVE OWINGS MILLS, MD 21117 PH: 410-701-4000 BALTIMORERAVENS.COM TWITTER: @RAVENS TWO-TIME WORLD CHAMPIONS: SUPER BOWL XXXV (2000) & SUPER BOWL XLVII (2012) PITTSBURGH STEELERS HARBS SAYS VS. BALTIMORE RAVENS JOHN HARBAUGH ON THE RAVENS’ APPROACH ENTERING WEEK 9: “You get right back in the lab, you get right back on the practice field, (4-2-1) WEEK 9 – SUNDAY, NOV. 4, 2018 (4-4) weight room, meeting room, JUGS machine, whatever it might be for 1 P.M. ET – M&T BANK STADIUM (71,008) your position, and you go back to work. You don’t lament it. Yes, [losing] stings. It hurts. Every time you think about it, it bothers you, because JUST THE FACTS nobody wants to lose a football game. You have an opportunity, and then it’s lost. But you have to make it up now. You have to go win more • After playing four of their past five on the road, the Baltimore games in the future than you would have had to previously. So, you go Ravens (4-4) return home to face the rival Pittsburgh Steelers back to work, and all of our players look at it that way.” (4-2-1) in a Week 9 battle at M&T Bank Stadium (1 p.m. kickoff). Pittsburgh has won three-straight games (and four of its last five), Kevin Byrne - Senior Vice President of Public/Community Relations while the Ravens look to bounce back from two-consecutive defeats. INJURY UPDATEChad Steele - Vice President of Public Relations v Patrick Gleason - Director of Public Relations - Public Relations Manager v - Publications/Public Relations Specialist • Last Sunday at Carolina, things started well in the Ravens’ 36-21 Three Ravens starters have missed theTom past Valente two games: CB Marlon Marisol Renner loss to the Panthers. -

SIGNED by YOUR FAVORITE RAVENS PLAYERS on Saturday

For Immediate Release Sarah Hund-Brown Rape Crisis Invention Service of Carroll County (410)-857-0900 [email protected] WIN AUTOGRAPHED HIGH HEELS - SIGNED BY YOUR FAVORITE RAVENS PLAYERS On Saturday April 9, 2011 Rape Crisis Invention Service of Carroll County (RCIS) will hold its 3rd Annual Walk a Mile in Her Shoes event. In honor of the event, RCIS is raffling a pair of high heels autographed by popular Ravens players. Raffle tickets are currently available for purchase online and at the RCIS office. Tickets are $5.00 each or 3 for $10.00 and the winner will be announced at the event on April 9th, you do not however need to be present to win. This is your chance to get a one of a kind keepsake and support a great cause! Signatures include….. Coach John Harbaugh Coach Jim Zorn #74 Michael Oher #77 Matt Birk #27 Ray Rice #92 Haloti Ngata #60 Digger Bujnoch #62 Terrence Cody #46 Morgan Cox #86 Todd Heap #58 Jason Phillips #54 Prescott Burgess Qadry “the Missile” Ismail, member of the 2000 Baltimore Ravens Super Bowl team With Bonus Signature: Jeremy Guthrie, Oriole Pitcher Why a pair of high heels? Because Walk a Mile in Her shoes asks men to literally walk a mile in women's high-heeled shoes to show their support for ending violence against women. While it's not easy walking in these shoes, it gets the community talking about the important issues that surround sexual violence. Rape Crisis Intervention Service of Carroll County (RCIS) is a private, non-profit agency serving Carroll County, Maryland, since 1978. -

All-Nfc North Team

ALL-NFC NORTH TEAM By Bob McGinn Posted: Dec. 31, 2005 Scouts from each of the NFC North teams were asked last week to rank the top three players in the division at each position. They were not permitted to vote for their own players, and none of the comments that follow in the position-by-position rundown was made by a scout about a player on his own team. A first-place vote was worth three points, a second-place vote was worth two and a third-place vote was worth one. Asterisks denote unanimous selections. OFFENSE NO. 1 WIDE RECEIVER: *Muhsin Muhammad (Chi.), 9 points. Others: Donald Driver (GB), 7; Roy Williams (Det.), 5; Travis Taylor (Minn.), 3. Comments: Muhammad dropped 11 passes and cost the Bears $12 million in signing bonus, but he was light years better than the No. 1 from '94, David Terrell. "It's a bad group," one scout said. "If (Rex) Grossman had been the quarterback it'd have been easier to determine where Muhammad is at in his career." Driver had one of his finest seasons. "He's still a better 2 than he is a 1," one scout said. Williams ranks as a two-year disappointment. "He has to understand the difference between being hurt and being injured," one scout said. LEFT TACKLE: Chad Clifton (GB), 8. Others: Jeff Backus (Det.) and John Tait (Chi.), 6; Bryant McKinnie (Minn.), 4. Comments: Clifton had too many penalties but made first team for the third year in a row. "He's close to elite," one scout said. -

Book Title Author / Publisher Year

Parker Career Management Collection BOOK TITLE AUTHOR / PUBLISHER YEAR 10 Insider Secrets to a Winning Job Search Todd Bermont 2004 100 Best Nonprofits To Work For Leslie Hamilton & Robert Tragert 2000 100 Greatest Ideas For Building the Business of Your Dreams Ken Langdon 2003 100 Top Internet Job Sites Kristina Ackley 2000 101 Great Answers to the Toughest Interview Questions Ron Fry 2000 175 High-Impact Cover Letters Richard H. Beatty 2002 175 High-Impact Cover Resumes Richard H. Beatty 2002 201 Best Questions to Ask on Your Interview John Kador 2002 25 Top Financial Firms Wetfeet 2004 9 Ways of Working Michael J. Goldberg 1999 A Blueprint For Success Joe Weller 2005 A Message from Garcia Charles Patrick Garcia 2003 A New Brand World Scot Bedbury with Stephen Fenichell 2002 A.T. Kearney Vault 2006 Accenture Vault 2006 Accenture Vault 2006 Accounting Vault 2006 Accounting Wetfeet 2006 Ace Your Case II: Fifteen More Consulting Cases WetFeet 2006 Ace Your Case IV: The Latest and Greatest WetFeet 2006 Ace Your Case VI: Mastering the Case WetFeet 2006 Ace your Case! Consulting Interviews WetFeet 2006 Ace Your Cases III: Practice Makes Perfect WetFeet 2006 Ace Your Interview! (2 copies) WetFeet 2004 Advertising Vault 2006 All About Hedge Funds Robert A. Jaeger 2003 All You Need to Know About the Movie and TV Business Gail Resnik and Scott Trost 1996 All You Need to Know About the Music Business Donald S. Passman 2003 American Management Systems Vault 2002 Ask the Headhunter Nick A. Corcodilos 1997 Asset Management & Retail Brokerage Wetfeet -

Week 14 Injury Report - Friday

FOR USE AS DESIRED NFL-PER-14 12/9/05 WEEK 14 INJURY REPORT - FRIDAY Following is a list of quarterback injuries for Week 14 Games (December 11-12): Jacksonville Jaguars Out Byron Leftwich (ankle) New York Jets Out Jay Fiedler (right shoulder) St. Louis Rams Out Marc Bulger (right shoulder) Tennessee Titans Questionable Steve McNair (back) Cleveland Browns Probable Trent Dilfer (knee) Green Bay Packers Probable Brett Favre (right hand) New England Patriots Probable Tom Brady (right shoulder) Pittsburgh Steelers Probable Ben Roethlisberger (right thumb) Pittsburgh Steelers Probable Charlie Batch (right hand) Following is a list of injured players for Week 14 Games (December 11-12): HOUSTON TEXANS (1-11) AT TENNESSEE TITANS (3-9) Houston Texans OUT DE Junior Ioane (calf) QUESTIONABLE LB Frank Chamberlin (hamstring); WR Jabar Gaffney (ankle); CB Lewis Sanders (hip) PROBABLE RB Domanick Davis (knee); DE Robaire Smith (neck); DE Gary Walker (knee) Listed players who did not participate in "team" practice: (Defined as missing any portion of 11-on-11 team work) LB Frank Chamberlin; RB Domanick Davis; WR Jabar Gaffney; WED DE Junior Ioane; CB Lewis Sanders; DE Robaire Smith; DE Gary Walker THURS RB Domanick Davis; DE Junior Ioane; CB Lewis Sanders FRI DE Junior Ioane; CB Lewis Sanders Tennessee Titans OUT TE Erron Kinney (knee); WR Roydell Williams (wrist) QUESTIONABLE WR Drew Bennett (knee); RB Chris Brown (ankle); DE Travis LaBoy (elbow); QB Steve McNair (back/ankle); WR Sloan Thomas (groin) Listed players who did not participate in "team" practice: (Defined as missing any portion of 11-on-11 team work) WR Drew Bennett; RB Chris Brown; TE Erron Kinney; DE Travis WED LaBoy; QB Steve McNair; WR Sloan Thomas; WR Roydell Williams RB Chris Brown; TE Erron Kinney; DE Travis LaBoy; QB Steve THURS McNair; WR Sloan Thomas; WR Roydell Williams RB Chris Brown; TE Erron Kinney; QB Steve McNair; WR Sloan FRI Thomas; WR Roydell Williams ST. -

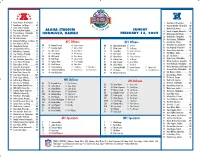

NFC Defense ALOHA STADIUM HONOLULU, HAWAII AFC Offense

4 Adam Vinatieri, New England. K 2 David Akers, Philadelphia. K 9 Drew Brees, San Diego . QB 5 Donovan McNabb, Philadelphia . QB 9 Shane Lechler, Oakland . P 7 Michael Vick, Atlanta . QB 12 Tom Brady, New England. QB ALOHA STADIUM SUNDAY 11 Daunte Culpepper, Minnesota. QB 18 Peyton Manning, Indianapolis . QB HONOLULU, HAWAII FEBRUARY 13, 2005 17 Mitch Berger, New Orleans . P 20 Tory James, Cincinnati . CB 20 Ronde Barber, Tampa Bay . CB 20 Ed Reed, Baltimore . SS 20 Brian Dawkins, Philadelphia . FS 21 LaDainian Tomlinson, San Diego . RB AFC Offense 20 Allen Rossum, Atlanta. KR 22 Nate Clements, Buffalo . CB NFC Offense 21 Tiki Barber, New York Giants . RB 24 Champ Bailey, Denver . CB WR 88 Marvin Harrison 80 Andre Johnson WR 87 Muhsin Muhammad 87 Joe Horn 26 Lito Sheppard, Philadelphia . CB 24 Terrence McGee, Buffalo . CB LT 75 Jonathan Ogden 77 Marvel Smith LT 71 Walter Jones 72 Tra Thomas 30 Ahman Green, Green Bay. RB 32 Rudi Johnson, Cincinnati . RB LG 66 Alan Faneca 54 Brian Waters LG 73 Larry Allen 76 Steve Hutchinson 43 Troy Polamalu, Pittsburgh . SS C 68 Kevin Mawae 64 Jeff Hartings C 57 Olin Kreutz 78 Matt Birk 31 Roy Williams, Dallas . SS 47 John Lynch, Denver . FS RG 68 Will Shields 54 Brian Waters RG 62 Marco Rivera 76 Steve Hutchinson 32 Dre’ Bly, Detroit . CB 49 Tony Richardson, Kansas City . FB RT 78 Tarik Glenn 77 Marvel Smith RT 76 Orlando Pace 72 Tra Thomas 32 Michael Lewis, Philadelphia. SS 51 James Farrior, Pittsburgh . ILB TE 85 Antonio Gates 88 Tony Gonzalez TE 83 Alge Crumpler 82 Jason Witten 33 William Henderson, Green Bay . -

Newton Wrestling

NEWTON WRESTLING 10 REASONS WHY FOOTBALL PLAYERS SHOULD WRESTLE 1. Agility--The ability of one to change the position of his body efficiently and easily. 2. Quickness--The ability to make a series of movements in a very short period of time. 3. Balance--The maintenance of body equilibrium through muscular control. 4. Flexibility--The ability to make a wide range of muscular movements. 5. Coordination--The ability to put together a combination of movements in a flowing rhythm. 6. Endurance--The development of muscular and cardiovascular-respiratory stamina. 7. Muscular Power (explosiveness)--The ability to use strength and speed simultaneously. 8. Aggressiveness--The willingness to keep on trying or pushing your adversary at all times. 9. Discipline--The desire to make the sacrifices necessary to become a better athlete and person. 10. A Winning Attitude--The inner knowledge that you will do your best - win or lose. NFL FOOTBALL PLAYERS WHO HAVE WRESTLED "I would have all my offensive linemen wrestle if I could." -John Madden - Hall of Fame NFL Coach I'm a huge wrestling fan. Wrestlers have so many great qualities that athletes need to have." - Bob Stoops - Oklahoma Sooners Head Football Coach Ray Lewis*, Baltimore Ravens – 2x FL State Champ - Bo Jackson*, RB, Oakland Raiders - Tedy Bruschi*, ILB, New England Patriots - Willie Roaf*, OT, New Orleans Saints - Warren Sapp*, DT Tampa Bay Buccaneers – FL State Champ Roger Craig*, RB, San Francisco 49’ers - Larry Czonka**, RB, Miami Dolphins - Tony Siragusa*, DT, Baltimore Ravens NJ State Champ - Ricky Williams*, RB, Miami Dolphins -Dahanie Jones, LB, New York Giants - Ronnie Lott**, DB, San Francisco 49’ers - Jim Nance, FB, New England Patriots NCAA Champ - Dan Dierdorff**, OT, St. -

WHO DO YOU THINK YOU ARE? BJORN NITTMO? Kicker Bjorn Nittmo Chased His NFL Dream for More Than a Decade, Including a Stop in Training Camp with the Buffalo Bills

WHO DO YOU THINK YOU ARE? BJORN NITTMO? Kicker Bjorn Nittmo chased his NFL dream for more than a decade, including a stop in training camp with the Buffalo Bills. He became a recurring character on 'Late Night with David Letterman.' A head injury left Nittmo so shattered that he walked out on his wife and four children. Years later, he continues to drop in, unannounced and unkempt, before taking off again. His estranged family wants him to get help before it's too late. By Tim Graham / News Sports Reporter Illustration by Daniel Zakroczemski / Buffalo News Published Sept. 1, 2016 Bjorn Nittmo is somewhere out there, presumably in the Arizona mountains, maybe installing home-satellite systems but almost certainly running from himself. Eleven years ago he stopped coming home to his wife and four children. The youngest was 6 months old. He had lost part of his memory and still complains about the constant howling in his head from a concussive whomp. He has filed for bankruptcy and faced at least six civil judgments or liens. At some point he began using a different name. There might be a sinister reason to take on an alias, or perhaps he simply grew tired of people asking if he was that Bjorn Nittmo. Yes, he’s the same guy David Letterman introduced in 1989 as “the only Bjorn Nittmo in the New Jersey phonebook.” In actuality he’s the only Bjorn Nittmo in the world, though he is more peculiar than even that. Nittmo was the left-footed, southern-drawled, Swedish placekicker the media treated like a geegaw from a Cracker Barrel store. -

Or Enon I Thursdoy Jon 25 1990 HUNTINGTON

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar The Parthenon University Archives Spring 1-25-1990 The Parthenon, January 25, 1990 Marshall University Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon Recommended Citation Marshall University, "The Parthenon, January 25, 1990" (1990). The Parthenon. 2757. https://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon/2757 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Parthenon by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Marshall University or enon I Thursdoy Jon 25 1990 HUNTINGTON . V/. VA. Vol 90. No 55 1 Students lose use of computers By Mary Beth Torlone ing is still available. the center. Dr. Dery} R. Leaming said the Report• •0ur budget request to the College of center shouldn't have to struggle for exis Liberal Arts last semester hasn't been re tence, but underfunding is a problem. sponded to: Hatfield said. "There is no Leaming said he was going to talk with It may be back to pen and paper for money forthcoming, so with no money, we administrators Wednesday about the students hoping to use the Writing Center's have no choice.• center's financial problems. word proce8801'8 this semester. · The COLA subsidizes the center, and the Dr. Robert S. Gerke, chairman of the A lack of funding has caused the College had Department of English made a large initial Department of English, said money :-:•:::::::::::::::::::::.:,:;:::::::::,:::::)i(=f i:::::,::•:•:•:•:::::::::::':::;:;::~ · ········ ··· of Liberal Arts and the Department of investment, according to Hatfield. -

Special Edition

The Patriot Special Issue January 21, 2005 Senior Directed Cabaret takes center stage Jamie Valentine ‘05 direct, and this year’s directors are Meghan Mucciarelli and Mike The Senior Directed Cabaret is a DiMatessa. tradition begun ten years ago with the When she found out, Mucciarelli class of 1996. It was started as a said, “I jumped up and down and fundraiser for Project Graduation, screamed like a little girl, honestly.” which was also founded that same year. DiMatessa said, “I’ve wanted to In the past decade, this show has do this since freshman year. I want to earned a reputation as an off-the-wall be a director, so this is a great chance funny and very relatable production. to get some experience. And I was In ’96, then-seniors Beth excited to work with Meghan.” Wodnick and Brian Nocella were the Directing a show like this one is first directors. Since then, two seniors no easy task. The Senior Directed who are dedicated to theater at Cabaret is made up of several skits, all Township have been chosen by the selected, cast, and directed by previous year’s cast and crew as co- Mucciarelli and DiMatessa. Over the directors every year. summer, they read through dozens of It is an honor to be chosen to plays and episodes of TV shows to decide which ones would work best. Jamie Valentine / The Patriot The chosen skits range Directors Mike DiMatessa (left) and Meghan Mucciarelli from serious to romantic (center) work on a scene with actor, Carl Jewell ‘07. -

The Blind Side

The Blind Side by Gwil Harris Page : 1 The Blind Side Contents Chapter 1 2 Chapter 2 2 Chapter 3 2 Chapter 4 3 Chapter 5 4 Page : 2 The Blind Side Chapter 1 Rough Beginnings 17-year-old Michael Oher has been in foster care with different families in Memphis, Tennessee, due to his mother's drug addiction. Every time he is placed in a new home, he runs away. His friend's father, on whose couch Mike has been sleeping, asks Burt Cotton, the coach of Wingate Christian School, to help enrol his son and Mike. Impressed by Mike's size and athleticism, Cotton gets him admitted despite a poor academic record. Michael walks out of school when he says hi to some children and they leave. Soon Michael is befriended by a boy named S.J. He suggests that Michael smiles at the children knowing that he is trying to be friendly to them. S.J.'s mother Leigh Anne Tuohy is a strong-minded interior designer and the wife of wealthy businessman Sean Tuohy. Leigh Anne notices Michael and asks S.J. who he is and is told he is Big Mike. Chapter 2 Misery After school staff tell Michael that his father passed away, leaving Michael homeless, Michael seeks shelter at a when she learns he intends to spend the night huddled outside laundrette. the school gym. When they drive away, Leigh Anne tells Sean to turn the car around and she sees and tells Michael that the gym Later, Leigh Anne, S.J. and Sean watch is closed.