(2017) 'Places and Spaces : Some

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bishop Press, Press, January May 30Th, 9Th, 2010.2009 Page 1 BURNS NIGHT EVENT TRAIN STATION SET for Bishop Auckland Town Hall Band

Issue No. 21 Holdforth Interiors Holdforth Crest, B.A. Tel: 01388 664777 Fax: 01388 665982 Soft Furnishings, Your local Curtains, Alterations Community Newspaper (both clothing & soft furnishings) Bishop Auckland, Saturday, January 9th, 2010. Telephone/Fax: 01388 775896 www.bishoppress.com Free Estimates Email: [email protected] - Duty journalist 0790 999 2731 No job too small Published at 3-4 First Floor Offices, Shildon Town Council, Civic Hall Square, Shildon, DL4 1AH. Competitive Rates PUBLIC CONSULTATION TO BE FREE LIFE HELD ON BRIDGE CLOSURE SKILLS COURSE A week-long People in Bishop Auckland part of the session, which will public exhibition are being offered the chance to involve a DIY lesson, where will provide join in free basic skills classes experts from Gentoo will show information to help them get the most out participants how to build flat- on an essential of life. pack furniture. scheme to repair Anyone can sign up for the Course co-ordinator, Damian a busy road half-day courses and go home Pearson, said, “We have had a bridge in Bishop with a piece of furniture they really positive response from Auckland. built themselves. the people who have done our Cockton Hill The courses have been held course so far. Railway Bridge regularly for the past year by “It is aimed at anyone in the will be closed to housing management company area and participants get to vehicles for up to Dale & Valley Homes and have keep what they build.” five weeks while proved popular with those who The next course will take Durham County have signed up. -

Escomb Saxon Church

Escomb Saxon Church The church was built around 675 AD with stone probably from the Roman Fort at Binchester. It was originally thought that the church was an offshoot of one of the local monasteries for example Whitby or Hartlepool, but this is only one of several possibilities as there are no known written records until 990 AD. Escomb is situated two miles west of Bishop Auckland in the Wear Valley. The church is one of five parishes grouped with Etherley, Hamsterley, Witton Park and Witton-le-Wear. Our church is on the national register of the Small Pilgrim Places Network. These places are small, spiritual oases, offering an atmosphere that encourages stillness, prayer and reflection for people of all faiths or none. Guides available by arrangement if required. Please contact us or visit our website for details of services. When is it on? Time of day Morning Afternoon Evening Session Day time and evening. information Who to contact Contact name Elisheva Mechanic Contact Vicar position Telephone 01388 768 898 E-mail [email protected] Website escombsaxonchurch.co.uk Where to go Name Escomb Church Address Escomb Green Escomb County Durham Postcode DL14 7SY Local Offer Local Offer Interior not accessible by wheelchair. description Disclaimer Durham County Council's Families Information Service does not promote nor endorse the services advertised on this website. Anyone seeking to use/access such services does so at their own risk and may make all appropriate enquiries about fitness for purpose and suitability to meet their needs. Call the Families Information Service: 03000 269 995 or email: [email protected] Disclaimer: Durham County Council's Families Information Service encourages and promotes the use of plain English. -

Drjonespodiatryleaflet.Pdf

DARLINGTON NHS Foundation Trust Hundens Rehabilitation Centre Building A Hundens Willington Health Centre DERWENTSIDE EASINGTON Chapel Street, Willington DL15 0EQ Service Lane Darlington DL1 1JE Shotley Bridge Community Hospital Murton Clinic delivered by County Durham & Darlington NHS Service delivered by County Durham & Consett DH8 0NB 21 Woods Terrace, Murton SR7 9AG Foundation Trust. Darlington NHS Foundation Trust. Service delivered by County Durham & Service by NHS City Hospitals Sunderland Darlington NHS Foundation Trust CDDFT provide assessment and ongoing care at CDDFT provide assessment and ongoing care Peterlee Community Hospital O’Neill Drive, the clinics indicated above, they also provide at the clinics indicated above, they also Stanley Primary Care Centre Clifford Road, Peterlee SR8 5UQ Service by North Tees & following an initial assessment clinics at the provide following an initial assessment clinics Stanley DH9 0AB Service delivered by County Hartlepool NHS Foundation Trust following venues:- at the following venues:- Durham & Darlington NHS Foundation Trust. Cockfield GP Surgery Peterlee Health Centre Gainford GP Surgery Flemming Place, Peterlee SR8 1AD Evenwood GP Surgery CDDFT provide assessment and ongoing care at Whinfield Medical Practice Whinbush Way, Service by Minor Ops Limited Middleton-in-Teasdale GP Surgery the clinics indicated above, they also provide Darlington DL1 3RT Service by Minor Ops Limited following an initial assessment clinics at the Seaham Primary Care Centre following venues:- DURHAM DALES -

THE RURAL ECONOMY of NORTH EAST of ENGLAND M Whitby Et Al

THE RURAL ECONOMY OF NORTH EAST OF ENGLAND M Whitby et al Centre for Rural Economy Research Report THE RURAL ECONOMY OF NORTH EAST ENGLAND Martin Whitby, Alan Townsend1 Matthew Gorton and David Parsisson With additional contributions by Mike Coombes2, David Charles2 and Paul Benneworth2 Edited by Philip Lowe December 1999 1 Department of Geography, University of Durham 2 Centre for Urban and Regional Development Studies, University of Newcastle upon Tyne Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Scope of the Study 1 1.2 The Regional Context 3 1.3 The Shape of the Report 8 2. THE NATURAL RESOURCES OF THE REGION 2.1 Land 9 2.2 Water Resources 11 2.3 Environment and Heritage 11 3. THE RURAL WORKFORCE 3.1 Long Term Trends in Employment 13 3.2 Recent Employment Trends 15 3.3 The Pattern of Labour Supply 18 3.4 Aggregate Output per Head 23 4 SOCIAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL DYNAMICS 4.1 Distribution of Employment by Gender and Employment Status 25 4.2 Differential Trends in the Remoter Areas and the Coalfield Districts 28 4.3 Commuting Patterns in the North East 29 5 BUSINESS PERFORMANCE AND INFRASTRUCTURE 5.1 Formation and Turnover of Firms 39 5.2 Inward investment 44 5.3 Business Development and Support 46 5.4 Developing infrastructure 49 5.5 Skills Gaps 53 6. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 55 References Appendices 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 The scope of the study This report is on the rural economy of the North East of England1. It seeks to establish the major trends in rural employment and the pattern of labour supply. -

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society Unwanted

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society baptism birth marriage No Gsurname Gforename Bsurname Bforename dayMonth year place death No Bsurname Bforename Gsurname Gforename dayMonth year place all No surname forename dayMonth year place Marriage 933ABBOT Mary ROBINSON James 18Oct1851 Windermere Westmorland Marriage 588ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul1869 Tynemouth Marriage 935ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 Jul1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland Marriage1561ABBS Maria FORDER James 21May1861 Brooke, Norfolk Marriage 1442 ABELL Thirza GUTTERIDGE Amos 3 Aug 1874 Eston Yorks Death 229 ADAM Ellen 9 Feb 1967 Newcastle upon Tyne Death 406 ADAMS Matilda 11 Oct 1931 Lanchester Co Durham Marriage 2326ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth SOMERSET Ernest Edward 26 Dec 1901 Heaton, Newcastle upon Tyne Marriage1768ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16Oct1849 Coughton Northampton Death 1556 ADAMS Thomas 15 Jan 1908 Brackley, Norhants,Oxford Bucks Birth 3605 ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth 18 May 1876 Stockton Co Durham Marriage 568 ADAMSON Annabell HADAWAY Thomas William 30 Sep 1885 Tynemouth Death 1999 ADAMSON Bryan 13 Aug 1972 Newcastle upon Tyne Birth 835 ADAMSON Constance 18 Oct 1850 Tynemouth Birth 3289ADAMSON Emma Jane 19Jun 1867Hamsterley Co Durham Marriage 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth Marriage1292ADAMSON Jane HARTBURN John 2Sep1839 Stockton & Sedgefield Co Durham Birth 3654 ADAMSON Julie Kristina 16 Dec 1971 Tynemouth, Northumberland Marriage 2357ADAMSON June PORTER William Sidney 1May 1980 North Tyneside East Death 747 ADAMSON -

Exploring the River Wear-Part 1

Armchair Adventurers Explore The River Wear G eog rap Part 1 from the Pennines to the outskirts of Durham hy A period. On the sea bed a limy ooze full of the rch y aeo eolog log G decaying skeletons of sea creatures built up. y Rivers washed down sand and gravel building His up deltas, and forests flourished on the deltas tory and swampy margins. Periodically the seas rose, drowned the deltas and forests and more Geology ooze was deposited; then sea levels dropped The River Wear rises in the North Pennines and and the deltas and forests returned. This cycle flows in an easterly direction to empty in the with compression gave rise to sedimentary North Sea at Sunderland. Weardale is in an rocks. The oozes became limestone, the sands, gravels and muds became shale and sandstone, and the forests became coal. Limestone and sandstone are resistant to erosion, whereas the softer shales wear away more easily. This contrast has produced the terraced hillsides which are characteristic of the whole area and the hard limestone outcrops form waterfalls created by the erosion. area designated for it’s Outstanding Natural Beauty. It is also a UNESCO Global Geopark. A Geopark is a place of outstanding geological heritage which is used to support sustainable development through conservation, education, interpretation and nature tourism. High Force Waterfall Limestone is the dominant rock in Upper The landscape has evolved over 500 million Weardale. Its main constituent, calcium years. During that time the valley has been carbonate, is soluble in rainwater which is liquid molten rock, desert,tropical sea,swamps, acidic and has eroded it to form sink holes, and an ice sheet. -

The Way of Life Route Gainford To

Northern Saints Trails The Way of Life Gainford to Durham Introduction This guide gives directions for travelling The Way of Life from Gainford to Durham. All the Northern Saints Trails use the same waymark shown on the left. The total distance is 47 kilometres or 29 miles. I have divided the route into 4 sections between 11 and 14 kilometres. This pilgrimage route, along with the Ways of Love, Light and Learning, all lead to the shrine of St Cuthbert in Durham. This route would have been the closest to St Cuthbert’s final journey in his coffin from Ripon to Durham in 995. He had died over 300 years earlier, but the monks who carried that coffin believed that by his spirit he continued to be alive and to guide them. This is why this route is called the Way of Life. Water is a symbol of life, so it is appropriate that the route begins by a well and a river. Section 1 Gainford to West Auckland – 11km Gainford Gainford is an ancient site. There was a Saxon church here in the 8th century. The presence of St Mary’s Well on the south side of the present church facing the river is significant, because the early Christians often chose and cleansed sites formerly associated with pagan devotion, which often centred on springs or water courses. Fragments of Anglo-Saxon sculpture found inside and around the church are further evidence that an ancient Christian community existed on this site, whilst sculpture combining Northumbrian and Norse motifs reflects subsequent Scandinavian settlement in the region. -

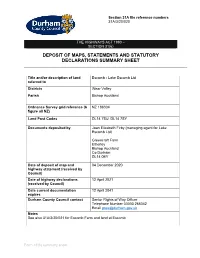

Escomb Farm and Land at Es

Section 31A file reference numbers 31A/3/20/021 THE HIGHWAYS ACT 1980 – SECTION 31(6) DEPOSIT OF MAPS, STATEMENTS AND STATUTORY DECLARATIONS SUMMARY SHEET Title and/or description of land Escomb Farm and land at Escomb referred to Districts Wear Valley Parish Bishop Auckland Ordnance Survey grid reference (6 NZ 183305, NZ 187305, NZ 189303 figure all NZ) Land Post Codes DL15 8AU, DL14 7SU, DL14 7SY, DL14 7SZ Documents deposited by Colin Michael Firby and Joan Elizabeth Firby Greencroft Farm Etherley Bishop Auckland Co Durham DL14 0EY Date of deposit of map and 04 December 2020 highway statement (received by Council) Date of highway declarations 12 April 2021 (received by Council) Date current documentation 12 April 2041 expires Durham County Council contact Senior Rights of Way Officer Telephone Number 03000 265342 Email [email protected] Notes See also 31A/3/20/020 for Escomb – Lake Escomb Ltd Form 31(6) summary sheet 1. Name of appropriate authority to which the application is addressed: Durham County Council 2. Name and full address (including postcode) of applicant Colin Michael Firby and Joan Elizabeth Firby Greencroft Farm Ethertey Bishop Auckland Co Durham DL14OEY 3. Status of applicant (tick relevant box or boxes): lam (a) X the owner of the land(s) described in paragraph 4. (b) making this application and the statementsldeclarations it contains on behalf of 4. Insert description ofthe land(s) to which the application relates (including full address and postcode): The land that the applicant owns is registered under three titles at Land Registry: (i) Title number DU360932 is Land at Escomb, Bishop Auckland, DL14 7SX. -

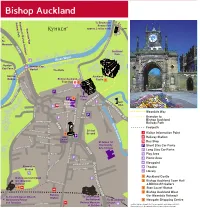

Bishop Auckland Map to Your Phone

Scan to download Bishop Auckland map to your phone: Brandon to Bishop Auckland Railway Path To Binchester Roman Fort Weardale Way approx. 2 miles north 6 L L I H To B O T Weardale S A689 L A I D Auckland Park River Wear Newton Newton Cap W Cap Farm Viaduct E The Batts A R C H A Skirlaw R Auckland E Bridge Bishop Auckland Castle 1 B N R Town Hall 2 I E D W G T E O S E N T AT DG C R ON E B A TH D P E OR A T N B O A R N Y E K Market A G 5 W ID Place S A R G 6 B N ST. Newgate N 8 Golf CLAYTO Shopping I 9 K GIB CHARE D Club T H U D . Centre ST ER t A L E SADD 9 R e O W 8 H e R T r I ET RE 6 H L A 1 T t T S Weardale Way Visitor Information Point Auckland Castle S L TER E M N S O S TE A D E W e E te S R 2 W Railway Station Bishop Auckland Town Hall & Mining Art Gallery VIC L Brandon to a TORIA A VE. L D g . Bishop Auckland 3 EDWARD STREET w Bus Stop Stan Laurel Statue A ewg E R Railway Path N . 6 N i 4 A T Short Stay Car Parks L 8 v Bishop Auckland West (for Weardale Railway) S e Y E 9 WESTGATE ROAD Footpath L N r R Long Stay Car Parks 5 Newgate Shopping Centre E O G H SUR TEES S Cricket T STRE a E ET B I 1 4 3 Ground Weardaleu Way Visitor Information Point Play AreaAuckland Castle 8 G n 2 G 6 PR l R INC B E’S ST Stan e Railway Station Picnic 2AreaBishop Auckland Town Hall & Mining Art Gallery E REE Brandon to T s E Laurel N Bishop Aucklands 3 Statue Bus Stop Stan Laurel Statue L DU St James 1st Viewpoint N RH AM STR . -

Deposit of Maps, Statements and Statutory Declarations Summary Sheet

Section 31A file reference numbers 31A/3/20/020 THE HIGHWAYS ACT 1980 – SECTION 31(6) DEPOSIT OF MAPS, STATEMENTS AND STATUTORY DECLARATIONS SUMMARY SHEET Title and/or description of land Escomb - Lake Escomb Ltd referred to Districts Wear Valley Parish Bishop Auckland Ordnance Survey grid reference (6 NZ 186304 figure all NZ) Land Post Codes DL14 7SU, DL14 7SY Documents deposited by Joan Elizabeth Firby (managing agent for Lake Escomb Ltd) Greencroft Farm Etherley Bishop Auckland Co Durham DL14 0EY Date of deposit of map and 04 December 2020 highway statement (received by Council) Date of highway declarations 12 April 2021 (received by Council) Date current documentation 12 April 2041 expires Durham County Council contact Senior Rights of Way Officer Telephone Number 03000 265342 Email [email protected] Notes See also 31A/3/20/021 for Escomb Farm and land at Escomb Form 31(6) summary sheet 1. Name ofappropriate authority to which the application is addressed: Durham County Council 2. Name and full address (including postcode) of applicant: Joan Elizabeth Firby Greencroft Farm Etherley Bishop Auckland Co Durham DL14OEY 3. Status of applicant (tick relevant box or boxes): lam (a) the owner of the land(s) described in paragraph 4. (b) X making this application and the statements/declarations it contains on behalf of Lake Escomb Limited who is the owner of the land(s) described in paragraph 4 and in my capacity as occupier and managing agent of that land. 4. Insert description ofthe land(s) to which the application relates (including full address and postcode): The land that Lake Escomb Limited owns is registered at Land Registry under title number DU309166 and is described as Land on the west side of Escomb Farm, Bishop Auckland, DL 14 7SX. -

VOLUME I (—), 1822. `Donations to the Society', Archaeol. Aeliana, Ser

VOLUME I (—), 1822. `Donations to the Society', Archaeol. Aeliana, ser. 1, I, 6 (—), 1833. `Runic gravestones found at Hartlepool', Gentleman's Mag., CIII, pt. 2, 218–20 (—), 1837. `Antiquities of Hexham abbey church', ibid., n. ser., VIII, 473–6 (—), 1838. `Sepulchral stones at Hartlepool', ibid., X, 536 (—), 1844. `Sepulchral stones found at Hartlepool', ibid., XXI, 187–8 (—), 1855a. `Donations to the Society', Archaeol. Aeliana, ser. 1, IV, 5 (—), 1855b. `Donations to the Society', ibid., 14 (—), 1855–7a. `Proceedings ..., 1855, no. 8', Proc. Soc. Antiq. Newcastle, ser. 1, I, 45–53 (—), 1855–7b. `Proceedings ..., 1856, no. 13', ibid., 89–107 (—), 1855–7c. `Proceedings ..., 1856, no. 14', ibid., 109–18 (—), 1855–7d. `Proceedings ..., 1856, no. 21', ibid., 179–85 (—), 1855–7e. `Proceedings ..., 1857, no. 30', ibid., 269–82 (—), 1860. `Exhibition 4th Jan. 1860', Archaeol. Aeliana, n. ser., IV, 254 (—), 1862–8a. `Meeting 18th May 1868', Trans. Architect. Archaeol. Soc. Durham Northumberland, I, xliv–vi (—), 1862–8b. `The church of St. Lawrence, Warkworth', ibid., 82–7 (—), 1862–8c. `St. Peter's, Monkwearmouth', ibid., 141–4 (—), 1862–8d. `Church reports, III: St. Peter's, Monkwearmouth', ibid., appendix, 1–8 (—), 1865a. `Chester-le-Street church', Archaeol. Aeliana, n. ser., VI, 188–9 (—), 1865b. `Runic legend from Monkwearmouth', ibid., 196 (—), 1865c. `Monthly Meeting 6th April 1864', ibid., 214 (—), 1869–79a. `Meetings 1868', Trans. Architect. Archaeol. Soc. Durham Northumberland, II, i–ii (—), 1869–79b. `Meeting 24th June 1869', ibid., v–vii (—), 1869–79c. `Meeting 28th–29th June 1869', ibid., vii–x (—), 1869–79d. `Meeting 4th Aug. 1871', ibid., xxx–xxxiv (—), 1869–79e. `Meeting 28th June 1872', ibid., xliv–xlvii (—), 1869–79f. -

Mead-Halls of the Oiscingas: a New Kentish Perspective on the Anglo-Saxon Great Hall Complex Phenomenon

Mead-halls of the Oiscingas: a new Kentish perspective on the Anglo-Saxon great hall complex phenomenon Article Published Version Creative Commons: Attribution 4.0 (CC-BY) Open Access Thomas, G. (2018) Mead-halls of the Oiscingas: a new Kentish perspective on the Anglo-Saxon great hall complex phenomenon. Medieval Archaeology, 62 (2). pp. 262-303. ISSN 0076-6097 doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00766097.2018.1535386 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/76215/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00766097.2018.1535386 Publisher: Maney Publishing All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Medieval Archaeology ISSN: 0076-6097 (Print) 1745-817X (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ymed20 Mead-Halls of the Oiscingas: A New Kentish Perspective on the Anglo-Saxon Great Hall Complex Phenomenon GABOR THOMAS To cite this article: GABOR THOMAS (2018) Mead-Halls of the Oiscingas: A New Kentish Perspective on the Anglo-Saxon Great Hall Complex Phenomenon, Medieval Archaeology, 62:2, 262-303, DOI: 10.1080/00766097.2018.1535386 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00766097.2018.1535386 © 2018 The Author(s).