Respondents' Response to Application for Temporary Injunction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November 2014 Al-Malih Shaqed Kh

Salem Zabubah Ram-Onn Rummanah The West Bank Ta'nak Ga-Taybah Um al-Fahm Jalameh / Mqeibleh G Silat 'Arabunah Settlements and the Separation Barrier al-Harithiya al-Jalameh 'Anin a-Sa'aidah Bet She'an 'Arrana G 66 Deir Ghazala Faqqu'a Kh. Suruj 6 kh. Abu 'Anqar G Um a-Rihan al-Yamun ! Dahiyat Sabah Hinnanit al-Kheir Kh. 'Abdallah Dhaher Shahak I.Z Kfar Dan Mashru' Beit Qad Barghasha al-Yunis G November 2014 al-Malih Shaqed Kh. a-Sheikh al-'Araqah Barta'ah Sa'eed Tura / Dhaher al-Jamilat Um Qabub Turah al-Malih Beit Qad a-Sharqiyah Rehan al-Gharbiyah al-Hashimiyah Turah Arab al-Hamdun Kh. al-Muntar a-Sharqiyah Jenin a-Sharqiyah Nazlat a-Tarem Jalbun Kh. al-Muntar Kh. Mas'ud a-Sheikh Jenin R.C. A'ba al-Gharbiyah Um Dar Zeid Kafr Qud 'Wadi a-Dabi Deir Abu Da'if al-Khuljan Birqin Lebanon Dhaher G G Zabdah לבנון al-'Abed Zabdah/ QeiqisU Ya'bad G Akkabah Barta'ah/ Arab a-Suweitat The Rihan Kufeirit רמת Golan n 60 הגולן Heights Hadera Qaffin Kh. Sab'ein Um a-Tut n Imreihah Ya'bad/ a-Shuhada a a G e Mevo Dotan (Ganzour) n Maoz Zvi ! Jalqamus a Baka al-Gharbiyah r Hermesh Bir al-Basha al-Mutilla r e Mevo Dotan al-Mughayir e t GNazlat 'Isa Tannin i a-Nazlah G d Baqah al-Hafira e The a-Sharqiya Baka al-Gharbiyah/ a-Sharqiyah M n a-Nazlah Araba Nazlat ‘Isa Nazlat Qabatiya הגדה Westהמערבית e al-Wusta Kh. -

Avoiding Last Period Defection Within Israeli-Palestinian Final

Breaking the Stalemate: Avoiding Last Period Defection within Israeli-Palestinian Final Status Negotiations through Statistical Modeling John J. Villa Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a B.A. with Honors From the Political Science Department at Duke University March 31, 2017 1 Forward: --First, I must thank the phenomenal Political Science Department at Duke University and my thesis advisor Dr. Michael C. Munger for their tremendous support while I developed my thesis and during my general education. Dr. Munger’s leadership, creativity, and generosity provided the foundation upon which I write to you, and his impact upon this publication was critical. --To Dr. Abdeslam E. M. Maghraoui, thank you for instructing me in three tremendous Middle East Studies courses and helping me establish the foundational aspects of this publication. Your mentorship and sharing of knowledge provided an entry point into subject matter far beyond anything I ever thought I would reach. -- To Dr. Mbaye Lo, thank you for your unwavering support, challenging materials, and educated discussions. Our long debates in your office are some of my fondest memories of my time in Durham. --To the staff of the Data Visualization Lab staff at Duke University consisting of Mark Thomas, Angela Zoss, John Little, and Jena Happ, your expertise, patience, and assistance in ArcGIS, Open Refine, and general data manipulation were extremely helpful during the computational portion of this publication and for that I thank you. --To Ryan Denniston, your assistance in Microsoft Excel functions and ArcGIS modeling was impeccable. This is, of course, in addition to your generosity, patience, and creatively which I’m sure were tested day after day coding together in the lab as you guided me through the ever-more complex ArcGIS models. -

The Israeli Colonization Activities in the Palestinian Territories During the 3Rd Quarter of 2015-2016

Applied Research Institute - Jerusalem (ARIJ) & Land Research Center – Jerusalem (LRC) [email protected] | http://www.arij.org [email protected] | http://www.lrcj.org The Israeli Colonization Activities in the Palestinian Territories during the 3rd Quarter of 2015-2016, (December 2015 – February 2016) December 2015 to February 2016 The Quarterly report highlights the chronology This report is prepared as part of of events concerning the Israeli Violations in the project entitled " Addressing Israeli Actions and its Land the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, the Polices int the oPT" which is confiscation and razing of lands, the uprooting financially supported by the EU and destruction of fruit trees, the expansion of and SDC. However, the content settlements and erection of outposts, the of this report is the sole brutality of the Israeli Occupation Army, the responsibility of ARIJ and do not Israeli settlers violence against Palestinian necessarily reflect those of the civilians and properties, the erection of donors checkpoints, the construction of the Israeli segregation wall and the issuance of military orders for the various Israeli purposes. 1 1 Applied Research Institute - Jerusalem (ARIJ) & Land Research Center – Jerusalem (LRC) [email protected] | http://www.arij.org [email protected] | http://www.lrcj.org Map 1: The Israeli Segregation Plan in the occupied Palestinian Territory 2 Applied Research Institute - Jerusalem (ARIJ) & Land Research Center – Jerusalem (LRC) [email protected] | http://www.arij.org [email protected] | http://www.lrcj.org Bethlehem Governorate (December 2015 - February 2016) The Israeli Violations in Bethlehem Governorate during the month of December 2015 • Israeli Occupation Army (IOA) stationed near Gilo settlement opened fire at Palestinian houses and land at Beir ‘Una and Al Jadawel areas in Beit Jala town, west of Bethlehem city. -

Israeli Population in the West Bank and East Jerusalem

Name Population East Jerusalem Afula Ramot Allon 46,140 Pisgat Ze'ev 41,930 Gillo 30,900 Israeli Population in the West Bank Neve Ya'akov 22,350 Har Homa 20,660 East Talpiyyot 17,202 and East Jerusalem Ramat Shlomo 14,770 Um French Hill 8,620 el-Fahm Giv'at Ha-Mivtar 6,744 Maalot Dafna 4,000 Beit She'an Jewish Quarter 3,020 Total (East Jerusalem) 216,336 Hinanit Jenin West Bank Modi'in Illit 70,081 Beitar Illit 54,557 Ma'ale Adumim 37,817 Ariel 19,626 Giv'at Ze'ev 17,323 Efrata 9,116 Oranit 8,655 Alfei Menashe 7,801 Kochav Ya'akov 7,687 Karnei Shomron 7,369 Kiryat Arba 7,339 Beit El 6,101 Sha'arei Tikva 5,921 Geva Binyamin 5,409 Mediterranean Netanya Tulkarm Beit Arie 4,955 Kedumim 4,481 Kfar Adumim 4,381 Sea Avnei Hefetz West Bank Eli 4,281 Talmon 4,058 Har Adar 4,058 Shilo 3,988 Sal'it Elkana 3,884 Nablus Elon More Tko'a 3,750 Ofra 3,607 Kedumim Immanuel 3,440 Tzofim Alon Shvut 3,213 Bracha Hashmonaim 2,820 Herzliya Kfar Saba Qalqiliya Kefar Haoranim 2,708 Alfei Menashe Yitzhar Mevo Horon 2,589 Immanuel Itamar El`azar 2,571 Ma'ale Shomron Yakir Bracha 2,468 Ganne Modi'in 2,445 Oranit Mizpe Yericho 2,394 Etz Efraim Revava Kfar Tapuah Revava 2,389 Sha'arei Tikva Neve Daniel 2,370 Elkana Barqan Ariel Etz Efraim 2,204 Tzofim 2,188 Petakh Tikva Nokdim 2,160 Alei Zahav Eli Ma'ale Efraim Alei Zahav 2,133 Tel Aviv Padu'el Yakir 2,056 Shilo Kochav Ha'shachar 2,053 Beit Arie Elon More 1,912 Psagot 1,848 Avnei Hefetz 1,836 Halamish Barqan 1,825 Na'ale 1,804 Padu'el 1,746 Rishon le-Tsiyon Nili 1,597 Nili Keidar 1,590 Lod Kochav Ha'shachar Har Gilo -

Israel's Religious Right and the Question Of

ISRAEL’S RELIGIOUS RIGHT AND THE QUESTION OF SETTLEMENTS Middle East Report N°89 – 20 July 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. NATIONAL-RELIGIOUS FRAGMENTATION AND RADICALISATION............ 3 III. THE TIME OF THE ULTRA-ORTHODOX............................................................... 12 IV. JEWISH ACTIVIST TOOLS ........................................................................................ 17 A. RHETORIC OR REALITY? ............................................................................................................17 B. INSTITUTIONAL LEVERAGE ........................................................................................................17 1. Political representation...............................................................................................................17 2. The military................................................................................................................................20 3. Education ...................................................................................................................................24 C. A PARALLEL SYSTEM ................................................................................................................25 V. FROM CIVIL DISOBEDIENCE TO VIOLENCE .................................................... -

Palestinian Economy and the Prospects for Its Recovery

40462 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized .UMBER $ECEMBER %CONOMIC-ONITORING2EPORTTOTHE!D(OC,IAISON#OMMITTEE ANDTHE0ROSPECTSFORITS2ECOVERY 4HE0ALESTINIAN%CONOMY 7EST"ANKAND'AZA 4HE7ORLD"ANK Contents FOREWORD – THE CONTEXT FOR THIS REPORT…………………………….……….i 1 – SUMMARY ASSESSMENT AND RECOMMENDATIONS………………………………1 I – THE NEED FOR RAPID ECONOMIC GROWTH…………………………………….1 II – GROWTH IN 2005 – ENCOURAGING BUT INCONCLUSIVE………………………..1 III – CREATING THE PRECONDITIONS FOR ECONOMIC RECOVERY: A PROGRESS REPORT………………………………………………..………….………….....2 IV – NEXT STEPS……………………………………………………………………5 2 – THE STATE OF THE PALESTINIAN ECONOMY: JANUARY THROUGH SEPTEMBER 2005……………………………………………6 I – OVERVIEW............................................................................................................................6 II – ECONOMIC OUTPUT…………………………………………………………….6 III – FISCAL AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS………………………………………7 IV – LABOR MARKET TRENDS……………………………………………………….9 3 – ECONOMIC RECOVERY: PRECONDITIONS AND PROSPECTS……………………10 I – MOVEMENT AND ACCESS………………………………………………………10 II – PALESTINIAN GOVERNANCE…………………………………………………..16 III – GROWTH PROSPECTS AND THE ROLE OF THE DONORS……………………….22 MAPS – GAZA, WEST BANK…………………………………………………………..24 ANNEX 1 – ECONOMIC SCENARIOS………………………………………………….26 ANNEX 2 – INDICATORS OF ECONOMIC REVIVAL…………………………………..29 ANNEX 3 – “TURNING THE CORNER” .……………………………………………..35 ANNEX 4 – AGREEMENT ON MOVEMENT AND ACCESS…………………………….39 ENDNOTES………………...………………………………………………………...44 -

Pdf | 509.42 Kb

Northern West Bank Disengagement: Zububa Settler Evacuation Roads Closures erected Access for the Disengagement Affected Area & Access for Palestinian Communities Rummana Evacuation Road Ti'innik (Military Zone) ‚ Checkpoints 'Arabbuna As Sa'aida Silat al Harithiya Al Jalama 'Anin Alternative 'Arrana Evacuation Road Deir Ghazala ") Roadblocks Dahiyat Sabah al Kheir Faqqu'a Khirbet Suruj Al Yamun Khirbet Abu 'Anqar Umm ar Rihan Hannanit Umm Qabub Open Road Kafr Dan Khirbet 'Abdallah al Yunis Barta'a ash Sharqiya Shaked Mashru' Beit Qad Khirbet ash Sheikh Sa'eed Al 'Araqa Jenin City Al Jameelat Beit Qad Affected Palestinian communities Reikhan Tura al Gharbiya Al Hashimiya Khirbet al Muntar al Gharbiya Tura ash Sharqiya At Tarem Khirbet al Muntar ash Sharqiya Jalbun Nazlat ash Sheikh Zeid (pop. 36,800) 'Aba Affected Palestinian communities are Umm Dar Kafr Qud Birqin WEST BANK Al Khuljan WadadDabi' Deir Abu Da'if Most affected towns or villages with a risk to be exposed Dhaher al 'Abed 'Akkaba Zabda to curfews, closures, clashes with the IDF Masqufet al 'Arab as Suweitat Palestinian communities Hajj Mas'ud Ya'bad Kufeirit and to settler violence. Imreiha Khirbet Sab'ein Qaffin Umm at Tut Ash Shuhada Affected Palestinian Affected Area Khermesh Jalqamus communities Mevo Dotan Al Mutilla Gaza JORDAN Bir al Basha Nazlat 'Isa Ad Damayra Qabatiya Baqa ash Sharqiya An Nazla ash Sharqiya Tannin Nazlat Abu Nar An Nazla al Wusta Arraba Al Hafira Khirbet Marah ar Raha Telfit ISRAEL An Nazla al Gharbiya Wadi EGYPT Khirbet Kharruba Du'oq Mirka Fahma -

Israel's Religious Right and the Question of Settlements

ISRAEL’S RELIGIOUS RIGHT AND THE QUESTION OF SETTLEMENTS Middle East Report N°89 – 20 July 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. NATIONAL-RELIGIOUS FRAGMENTATION AND RADICALISATION............ 3 III. THE TIME OF THE ULTRA-ORTHODOX............................................................... 12 IV. JEWISH ACTIVIST TOOLS ........................................................................................ 17 A. RHETORIC OR REALITY? ............................................................................................................17 B. INSTITUTIONAL LEVERAGE ........................................................................................................17 1. Political representation...............................................................................................................17 2. The military................................................................................................................................20 3. Education ...................................................................................................................................24 C. A PARALLEL SYSTEM ................................................................................................................25 V. FROM CIVIL DISOBEDIENCE TO VIOLENCE .................................................... -

An Update on Palestinian Movement, Access and Trade in the West Bank and Gaza

World Bank Technical Team Report, August 15, 2006 40461 An Update on Palestinian Movement, Access and Trade in the West Bank and Gaza Summary Public Disclosure Authorized Background This paper provides an updated assessment of movement and access for goods and people in WBG1, which was initiated by the World Bank after the December 2004 Ad Hoc Liaison Committee Meeting when all parties (including the Government of Israel and the Palestinian Authority) agreed that Palestinian economic revival was essential, that it required a major dismantling of today’s closure regime and that closure needed to be addressed from several perspectives at once. In today’s environment of confrontation and heightened risk, movement and access controls have increased and earlier relaxations have been reversed. However, the relationship between Palestinian economic revival and stability and Israeli security remain unarguable and of fundamental importance to both societies’ well-being. Recent initiatives by US-security advisor General Dayton to significantly enhance the security of the Karni crossing between Gaza and Israel in order to ensure an efficient and predicable corridor for trade recognizes this relationship. Public Disclosure Authorized Movement of goods Between Gaza and Israel Growth prospects for the West Bank and Gaza depend critically on its openness to trade. Prior to the Intifada, the flow of cargo into and out of Gaza was largely determined by market demand, with most cargo moving in convoys or through the (then) relatively simple Erez crossing. Today, all cargo flows between Israel and Gaza must be channeled through the Karni crossing point. From a low base of only 43 export trucks per day in the six months prior to the Israeli disengagement from Gaza, actual daily export numbers through mid-June 2006 have fallen to less than 25 trucks a day. -

Report on the Attacks of the Occupation Army and Settlers on Palestinian Agricultural Sector in the West Bank and Gaza Strip October 2020

Report on the Attacks of the Occupation Army and Settlers on Palestinian Agricultural Sector in the West Bank and Gaza Strip October 2020 The attacks of the occupation army and settlers during October, which coincides with the commencement of the olive harvest season in the Palestinian territories, led to burning, uprooting and destruction of more than 1,600 olive trees, in addition to confiscation and expulsion of shepherds from their lands. October also recorded dozens of shootings at fishermen and agricultural lands in the Gaza Strip. In this report, the agricultural committees monitored attacks committed in October. Military Orders, Confiscations and Demolition of Facilities Confiscation of a Bulldozer in Furush Beit Dajan / Nablus. • On 5/10/2020, Israeli occupation forces confiscated a bulldozer while it was digging a water reservoir for irrigation of crops in the village of Furush Beit Dajan in the Nablus District. • On 8/10/2020, Israeli occupation forces confiscated a tractor and a 4 Cubic Meters water tanker it was pulling, in the Al-Jiftlik area, north of Jericho. • On 8/10/2020, the occupation forces confiscated a bulldozer that was working on rehabilitating an agricultural road in the village of Ain Al-Baida in the northern Jordan Valley. 1 • On 10/13/2020, Israeli occupation forces confiscated a bulldozer in the municipality of Al- Zawiya, west of Salfit, detained its driver, while working to facilitate a dirt road, to allow citizens to reach their lands to pick the olive harvest, and released him at approximately 11:30 pm. • On 13/10/2020, Israeli occupation authorities issued a notification to stop construction four agricultural rooms in the town of Al-Khader, south of Bethlehem, under the pretext that the builders do not have construction permits. -

Postal Code Locality Name Comments

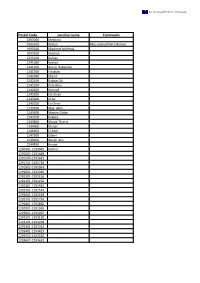

Postal Code Locality name Comments 1093000 Mechola 1093100 Rotem Also named Nahal Rotem 1093200 Shadmot Mechola 1093500 Maskiot 1225100 Banias 1241000 Keshet 1241200 Alonei Habashan 1241500 Yonatan 1242000 Sha'al 1242100 Kidmat Zvi 1242200 Kela Alon 1242400 Nimrod 1242600 Ein-Zivan 1243000 Ortal 1243200 Ein Kinia 1243500 Mas' adeh 1243600 Merom Golan 1243700 Bukata 1243800 Majdal Shams 1244000 Ghajar 1246600 El-Rom 1247300 Odem 1249300 Neveh Ativ 1249500 Aniam 1290101-1290945 Katzrin 1291001-1291448 1291504-1291642 1291701-1291739 1291802-1291954 1292001-1292040 1292101-1292156 1292201-1292256 1292301-1292462 1292501-1292542 1292601-1292638 1292701-1292730 1292801-1292860 1292901-1292926 1293001-1293065 1293101-1293130 1293201-1293208 1293301-1293352 1293401-1293423 1293502-1293550 1293601-1293632 1293701-1293767 1293802-1293920 1294001-1294156 1294201-1294342 1294402-1294575 1294601-1294728 1294801-1294835 1291500 Natur 1291700 Ramat Magshimim 1292000 Hispin 1292100 Nov 1292500 Avnei Eitan 1292700 Eli'ad 1293000 Kanaf 1293200 Kfar Haruv 1293400 Mevo Hama 1293600 Metzar 1293800 Afik 1294000 Ne'ot Golan 1294200 Gshur 1294400 Bnei Yehuda 1294600 Givat Yoav 1294800 Ramot 1294900 Ma'aleh Gamla 1295000 Had-Nes 1290503 Ta'asiot Golan A factory 3786200 Shaked 3786700 Hinanit 3787000 Rehan 4070202-4079316 Ariel 4481000 Sha'arei Tikva 4481300 Oranit 4481400 Elkana 4481500 Kiryat Netafim 4481600 Etz Efraim 4482000 Barkan 4482100 Barkan I.Z. 4482500 Ma'aleh Levonah 4482700 Rehelim 4482800 Eli 4482900 Kfar Tapuach 4483000 Shilo 4483100 Yitzhar 4483200 Shvut Rachel 4483300 Elon Moreh 4483400 Itamar 4483500 Bracha 4483900 Revava 4484100 Nofim 4484300 Yakir 4484500 Emanu'el 4485100 Alfei Menasheh 4485200 Ma'aleh Shomron 4485500 Karnei Shomron 4485600 Kdumim 4485700 Enav 4485800 Shavei Shomron 4486100 Avnei Hefetz 4486500 Zufim 4489000 Mevo Dotan 4489500 Hermesh 4584800 Nitzanei Shalom I.Z. -

An Unjust Settlement

A U S 1 )e Ecumenical Accompaniment Programme in Palestine and Israel (EAPPI) brings internationals to the West Bank to experience life under occupation. Ecumenical Accompaniers (EAs) provide protective presence to vulnerable communities, monitor and report human rights abuses and support Palestinians and Israelis working together for peace. When they return home, EAs campaign for a just and peaceful resolution to the Israeli/ Palestinian conflict through an end to the occupation, respect for international law and implementation of UN resolutions. Ecumenical Accompaniment Programme in Palestine and Israel (EAPPI) www.eappi.org )e EAPPI is a World Council of Churches programme Published by: EAPPI Editors: Nader Muaddi, Kimberly Meinecke, Gearóid Fitzgibbon, Michael Barnes, Karen Chalk Printer: Emerezian Est. [email protected] ISBN 978-2-8254-1552-8 September 2010 2 A U S )e Ecumenical Accompaniment Programme in Palestine and Israel (EAPPI) 3 F by Manuel Quintero EAPPI International Programme Coordinator From “living with them” to dispossession: a tale of Israeli settlements )e image of settlers - at least in some parts heeded the Pope’s call, and Indians continued of the world - has been greatly magnified by being treated as animals and deprived of their Hollywood films. In Hollywood’s characteristic livelihood for a long time. Resistance to colonial Manichean perspective of villains and heroes, oppression and exploitation was met with harsh settlers were the good guys who brought and exemplary repression: in Chile, the leader of civilization to the backward, dark-skinned the Mapuche people, Caupolican, was impaled; savage natives. Real history shows a very in India, sepoys were tied to the muzzles of different picture.