SIGNIFICANT PARALLELS Ln THEODORE DREISER's AN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Extra)ORDINARY MEN

(Extra)ORDINARY MEN: African-American Lawyers and Civil Rights in Arkansas Before 1950 Judith Kilpatrick* “The remarkable thing is not that black men attempted to regain their stolen civic rights, but that they tried over and over again, using a wide va- riety of techniques.”1 I. INTRODUCTION Arkansas has a tradition, beginning in 1865, of African- American attorneys who were active in civil rights. During the eighty years following the Emancipation Proclamation, at least sixty-nine African-American men were admitted to practice law in the state.2 They were all men of their times, frequently hold- * Associate Professor, University of Arkansas School of Law; J.S.D. 1999, LL.M. 1992, Columbia University, J.D. 1975, B.A. 1972, University of California-Berkeley. The author would like to thank the following: the historians whose work is cited here; em- ployees of The Arkansas History Commission, The Butler Center of the Little Rock Public Library, the Pine Bluff Public Library and the Helena Public Library for patience and help in locating additional resources; Patricia Cline Cohen, Professor of American History at the University of California, Santa Barbara, for reviewing the draft and providing comments; and Jon Porter (UA 1999) and Mickie Tucker (UA 2001) for their excellent research assis- tance. Much appreciation for summer research grants from the University of Arkansas School of Law in 1998 and 1999. Special thanks to Elizabeth Motherwell, of the Universi- ty of Arkansas Press, for starting me in this research direction. No claim is made as to the completeness of this record. Gaps exist and the author would appreciated receiving any information that might help to fill them. -

Download File

The Outward Turn: Personality, Blankness, and Allure in American Modernism Anne Claire Diebel Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Anne Claire Diebel All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Outward Turn: Personality, Blankness, and Allure in American Modernism Anne Claire Diebel The history of personality in American literature has surprisingly little to do with the differentiating individuality we now tend to associate with the term. Scholars of nineteenth- and twentieth-century American culture have defined personality either as the morally vacuous successor to the Protestant ideal of character or as the equivalent of mass-media celebrity. In both accounts, personality is deliberately constructed and displayed. However, hiding in American writings of the long modernist period (1880s–1940s) is a conception of personality as the innate capacity, possessed by few, to attract attention and elicit projection. Skeptical of the great American myth of self-making, such writers as Henry James, Theodore Dreiser, Gertrude Stein, Nathanael West, and Langston Hughes invented ways of representing individuals not by stable inner qualities but by their fascinating—and, often, gendered and racialized—blankness. For these writers, this sense of personality was not only an important theme and formal principle of their fiction and non-fiction writing; it was also a professional concern made especially salient by the rise of authorial celebrity. This dissertation both offers an alternative history of personality in American literature and culture and challenges the common critical assumption that modernist writers took the interior life to be their primary site of exploration and representation. -

WILL HE >JUSTIFY= the HYPE?

SATURDAY, APRIL 7, 2018 BLUE GRASS COULD BE WHITE OUT WILL HE >JUSTIFY= Assuming a potential snowstorm Friday night doesn=t put a THE HYPE? damper on things, a full field is set to go postward in Saturday=s GII Toyota Blue Grass S. The conversation about contenders must start with $1-million KEESEP yearling Good Magic (Curlin), who broke his maiden emphatically in the GI Breeders= Cup Juvenile at Del Mar en route to Eclipse Award honors. Heavily favored in the GII Xpressbet Fountain of Youth on seasonal debut at Gulfstream Mar. 3, he settled for a non-threatening third with no obvious excuse. Flameaway (Scat Daddy), second in the Mar. 10 GII Tampa Bay Derby behind expected scratch Quip (Distorted Humor) after annexing the GIII Sam F. Davis S. there in February, took a rained-off renewal of the GIII Bourbon S. in the Keeneland slop last October. Cont. p3 Justify | Benoit Photo IN TDN EUROPE TODAY ASTUTE AGENT HAS GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE >TDN Rising Star= Justify (Scat Daddy), almost certainly the Kelsey Riley sat down with Australia based Frenchman most highly regarded horse in the world to have not yet taken Louis Le Metayer to get his thoughts on various aspects of on stakes company, will get his class test on Saturday when he the Australian racing scene. Click or tap here to go straight faces the likes of MGISW Bolt d=Oro (Medaglia d=Oro) in the to TDN Europe. GI Santa Anita Derby. A 9 1/2-length jaw-dropping debut winner going seven panels here Feb. -

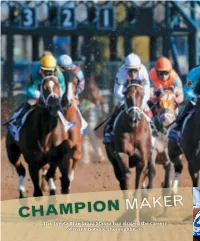

Champion Maker

MAKER CHAMPION The Toyota Blue Grass Stakes has shaped the careers of many notable Thoroughbreds 48 SPRING 2016 K KEENELAND.COM Below, the field breaks for the 2015 Toyota Blue Grass Stakes; bottom, Street Sense (center) loses a close 2007 running. MAKER Caption for photo goes here CHAMPION KEENELAND.COM K SPRING 2016 49 RICK SAMUELS (BREAK), ANNE M. EBERHARDT CHAMPION MAKER 1979 TOBY MILT Spectacular Bid dominated in the 1979 Blue Grass Stakes before taking the Kentucky Derby and Preakness Stakes. By Jennie Rees arl Nafzger’s short list of races he most send the Keeneland yearling sales into the stratosphere. But to passionately wanted to win during his Hall show the depth of the Blue Grass, consider the dozen 3-year- of Fame training career included Keeneland’s olds that lost the Blue Grass before wearing the roses: Nafzger’s Toyota Blue Grass Stakes. two champions are joined by the likes of 1941 Triple Crown C winner Whirlaway and former record-money earner Alysheba Instead, with his active trainer days winding down, he has had to (disqualified from first to third in the 1987 Blue Grass). settle for a pair of Kentucky Derby victories launched by the Toyota Then there are the Blue Grass winners that were tripped Blue Grass. Three weeks before they entrenched their names in his- up in the Derby for their legendary owners but are ensconced tory at Churchill Downs, Unbridled finished third in the 1990 Derby in racing lore and as stallions, including Calumet Farm’s Bull prep race, and in 2007 Street Sense lost it by a nose. -

Kentucky Derby, Flamingo Stakes, Florida Derby, Blue Grass Stakes, Preakness, Queen’S Plate 3RD Belmont Stakes

Northern Dancer 90th May 2, 1964 THE WINNER’S PEDIGREE AND CAREER HIGHLIGHTS Pharos Nearco Nogara Nearctic *Lady Angela Hyperion NORTHERN DANCER Sister Sarah Polynesian Bay Colt Native Dancer Geisha Natalma Almahmoud *Mahmoud Arbitrator YEAR AGE STS. 1ST 2ND 3RD EARNINGS 1963 2 9 7 2 0 $ 90,635 1964 3 9 7 0 2 $490,012 TOTALS 18 14 2 2 $580,647 At 2 Years WON Summer Stakes, Coronation Futurity, Carleton Stakes, Remsen Stakes 2ND Vandal Stakes, Cup and Saucer Stakes At 3 Years WON Kentucky Derby, Flamingo Stakes, Florida Derby, Blue Grass Stakes, Preakness, Queen’s Plate 3RD Belmont Stakes Horse Eq. Wt. PP 1/4 1/2 3/4 MILE STR. FIN. Jockey Owner Odds To $1 Northern Dancer b 126 7 7 2-1/2 6 hd 6 2 1 hd 1 2 1 nk W. Hartack Windfields Farm 3.40 Hill Rise 126 11 6 1-1/2 7 2-1/2 8 hd 4 hd 2 1-1/2 2 3-1/4 W. Shoemaker El Peco Ranch 1.40 The Scoundrel b 126 6 3 1/2 4 hd 3 1 2 1 3 2 3 no M. Ycaza R. C. Ellsworth 6.00 Roman Brother 126 12 9 2 9 1/2 9 2 6 2 4 1/2 4 nk W. Chambers Harbor View Farm 30.60 Quadrangle b 126 2 5 1 5 1-1/2 4 hd 5 1-1/2 5 1 5 3 R. Ussery Rokeby Stables 5.30 Mr. Brick 126 1 2 3 1 1/2 1 1/2 3 1 6 3 6 3/4 I. -

In Cold Blood, Half a Century On

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2009/nov/16/truman-capote-in-cold-blood In Cold Blood, half a century on Fifty years ago, Holcomb, Kansas was devastated by the slaughter of a local family. And then Truman Capote arrived in town . Truman Capote in the living room of the Clutter ranch. Photograph: AP Ed Pilkington @edpilkington Sunday 15 November 2009 River Valley farm stands at the end of an earth road leading out of Holcomb, a small town on the western edge of Kansas. You can see its pretty white gabled roof floating above a sea of corn stubble. The house is famous for the elm trees which line the drive, giving it the tranquil air of a French country lane. The trees are in poor shape though, and desperately in need of pruning; their branches, leafless now, protrude at wild angles. There's something else not quite right about the setting. There is a large "stop" sign at the entrance to the road, backed up by a metal barrier and a hand-written poster in red paint proclaiming: "No Trespassing. Private Drive." The warnings seem belligerent for such a peaceful spot. The explanation for these warnings lies about half a mile away in Holcomb's local park. A memorial plaque was unveiled there two months ago in honour of the former occupants of River Valley farm: the Clutter family, who lived in that house at the end of the elm drive until one tragic night half a century ago. The plaque carries a lengthy eulogy to the family, recording the many accomplishments of the father, Herb Clutter, and telling us that the family's leisure activities included "entertaining friends, enjoying picnics in the summer and participating in school and church events". -

Chris Mccarron Joins Team Valor International, Starts

May 1, 2018 CHRIS MCCARRON JOINS TEAM VALOR INTERNATIONAL, STARTS THIS WEEK HALL OF FAME RIDER JOINS EXECUTIVE TEAM AT KENTUCKY HOME BASE HIRE PART OF RESHAPING AND REFOCUSING AS STABLE REINVENTS ITSELF Chris McCarron has joined Team Valor International and will be part of the executive team of the far- flung organization. He starts this week and will be involved at Churchill Downs, where the operation races three runners (two in stakes) this week in Louisville. “As a Hall of Fame inductee and as the rider of such legendary racehorses as Alysheba and John Henry, Chris is one of the most recognizable people in racing,” CEO Barry Irwin said. “But it is for his abilities as a communicator, his horsemanship and his drive as an organizer that he has been brought aboard. “I have worked alongside Chris as part of the initiative to introduce Federal legislation to rein in the use of legal and illegal drugs in our sport and I have been very impressed with his communication skills and his passion for the best aspects of our game.” McCarron’s most recent major career achievement in racing came when he realized a nearly life-long dream of establishing and nurturing America’s first school for jockeys. Named the North American Racing Academy, it is the only school where aspiring jockeys can earn a college degree. McCarron started NARA in 2005 and left it in safe hands in 2014. He continues to be an overseer of NARA. After retiring from a record-breaking and storied career as a jockey, McCarron served a stint as general manager at Santa Anita. -

Lookbook a CAT CALLED SAM & a DOG NAMED DUKE

AW21 A CAT CALLED SAM & A DOG NAMED DUKE click here to VIEW OUR Lookbook VIDEO thebonniemob.com AW21 AW21 S STAINABLE A CAT CALLED SAM & RECYCLE ORG NIC A DOG NAMED DUKE This is the story of a cat called Sam and a dog named Duke. Everyone said that they couldn’t be friends, because cats and dogs aren’t allowed to like each other!!! But Sam and Duke were different, they were the best of friends and loved each other very much, they liked to hang out together with their owner, a famous artist called Andy Warhol. They threw parties for all the coolest cats and dogs of New York, where they would dance the night away looking up at the city skyline, when they spotted a shooting star they’d make wishes for a world filled with art and colour and fun and kindness.......... click here click here click here to for to VIEW COLLECTION VIEW OUR INSPIRATION runthrough VIDEO Video Video CULTURE T shirt click click here CAMPBELL here for Hareem pants to order line sheets online CANDY dress THUMPER #welovebonniemob tights 2 3 thebonniemob.com AW21 LIZ A Hat G NI R C LIBERTY O ABOUT US Playsuit C LEGEND We are The bonnie mob, a multi-award winning sustainable baby and O N childrenswear brand, we are a family business, based in Brighton, on the sunny T T O Blanket South Coast of England. We are committed to doing things differently, there are no differences between what we want for our family and what we ask from our brand. -

A Theological Reading of the Gideon-Abimelech Narrative

YAHWEH vERsus BAALISM A THEOLOGICAL READING OF THE GIDEON-ABIMELECH NARRATIVE WOLFGANG BLUEDORN A thesis submitted to Cheltenham and Gloucester College of Higher Education in accordance with the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts & Humanities April 1999 ABSTRACT This study attemptsto describethe contribution of the Abimelech narrative for the theologyof Judges.It is claimedthat the Gideonnarrative and the Abimelechnarrative need to be viewed as one narrative that focuseson the demonstrationof YHWH'S superiority over Baalism, and that the deliverance from the Midianites in the Gideon narrative, Abimelech's kingship, and the theme of retribution in the Abimelech narrative serve as the tangible matter by which the abstracttheological theme becomesnarratable. The introduction to the Gideon narrative, which focuses on Israel's idolatry in a previously unparalleled way in Judges,anticipates a theological narrative to demonstrate that YHWH is god. YHwH's prophet defines the general theological background and theme for the narrative by accusing Israel of having abandonedYHwH despite his deeds in their history and having worshipped foreign gods instead. YHWH calls Gideon to demolish the idolatrous objects of Baalism in response, so that Baalism becomes an example of any idolatrous cult. Joash as the representativeof Baalism specifies the defined theme by proposing that whichever god demonstrateshis divine power shall be recognised as god. The following episodesof the battle against the Midianites contrast Gideon's inadequateresources with his selfish attempt to be honoured for the victory, assignthe victory to YHWH,who remains in control and who thus demonstrateshis divine power, and show that Baal is not presentin the narrative. -

The College News, 1952-06-03, Vol. 38, No. 25 (Bryn Mawr, PA: Bryn Mawr College, 1952)

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Bryn Mawr College Publications, Special Bryn Mawr College News Collections, Digitized Books 1952 The olC lege News, 1952-06-03, Vol. 38, No. 25 Students of Bryn Mawr College Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/bmc_collegenews Custom Citation Students of Bryn Mawr College, The College News, 1952-06-03, Vol. 38, No. 25 (Bryn Mawr, PA: Bryn Mawr College, 1952). This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/bmc_collegenews/872 For more information, please contact [email protected]. " c:J " • - 'l'rut.. of 25 "WIld 1952 CoP)'rlabt. 20 VOL, XLVIII-NO, ARDMORE BRYN MAWR, PA" TUESDAY, JUNE 3, Bryn .hwr Collere, 1952 PRICE CENTS Bryn Mawr Winner Semel & Benedict a o Fosdick Avers M" Thomas Prize Of "Prix de Paris" Dividt: Fellowship T yl r Defends Urges Participation For Coming ear Seniors' .For Joyce Essay ' The moat important thing that Y Ll"ngul"stl"C Uses ( wi'ah to do is to urge all jun o Need The M. Carey Thomas Ellay i l:S The Bryn Mawr European Fe!. who are Jnte�ted to tr Prize, a warded annually to a mem at all y lowahlp haa this year been split, ouL lor the stated Ka- and awarded ,to two members Faith ber ot the Senior clal8 for the 'Prix. .. 01 Present Day Vital CherMlett.eIT,. .tec8l.t beat paper written in t.he courae ot Lushka '02, the graduating clasa. -

1 Breakfast at Tiffany's Truman Capote, 1958 I Am Always Drawn Back To

1 Breakfast at Tiffany's surrounded by photographs of ice-hockey stars, there is always a large bowl of fresh Truman Capote, 1958 flowers that Joe Bell himself arranges with matronly care. That is what he was doing when I came in. I am always drawn back to places where I have lived, the houses and their "Naturally," he said, rooting a gladiola deep into the bowl, "naturally I wouldn't have neighborhoods. For instance, there is a brownstone in the East Seventies where, got you over here if it wasn't I wanted your opinion. It's peculiar. A very peculiar thing during the early years of the war, I had my first New York apartment. It was one room has happened." crowded with attic furniture, a sofa and fat chairs upholstered in that itchy, particular red "You heard from Holly?" velvet that one associates with hot days on a tram. The walls were stucco, and a color He fingered a leaf, as though uncertain of how to answer. A small man with a fine rather like tobacco-spit. Everywhere, in the bathroom too, there were prints of Roman head of coarse white hair, he has a bony, sloping face better suited to someone far ruins freckled brown with age. The single window looked out on a fire escape. Even so, taller; his complexion seems permanently sunburned: now it grew even redder. "I can't my spirits heightened whenever I felt in my pocket the key to this apartment; with all its say exactly heard from her. I mean, I don't know. -

Annie Hall: Screenplay Pdf, Epub, Ebook

ANNIE HALL: SCREENPLAY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Woody Allen,Marshall Brickman | 128 pages | 21 Feb 2000 | FABER & FABER | 9780571202140 | English | London, United Kingdom Annie Hall: Screenplay PDF Book Photo Gallery. And I thought of that old joke, you know. Archived from the original on January 20, Director Library of Congress, Washington, D. According to Brickman, this draft centered on a man in his forties, someone whose life consisted "of several strands. Vanity Fair. Retrieved January 29, The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 10, All the accolades and praise encouraged me to pick up this script. Archived from the original on December 30, Rotten Tomatoes. And I'm amazed at how epic the characters can be even when nothing blockbuster-ish happens. Annie and Alvy, in a line for The Sorrow and the Pity , overhear another man deriding the work of Federico Fellini and Marshall McLuhan ; Alvy imagines McLuhan himself stepping in at his invitation to criticize the man's comprehension. Retrieved March 23, How we actually wrote the script is a matter of some conjecture, even to one who was intimately involved in its preparation. It was fine, but didn't live up to the hype, although that may be the hype's fault more than the script's. And I thought, we have to use this. It was a delicious and crunchy treat for its realistic take on modern-day relationships and of course, the adorable neurotic-paranoid Alvy. The Paris Review. Even in a popular art form like film, in the U. That was not what I cared about Woody Allen and the women in his work.