Identifying Key Habitat Features for Managing Breeding Southwestern Willow Flycatchers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southwestern Willow Flycatcher (Empidonax Traillii Extimus) Overview

Southwestern Willow Flycatcher (Empidonax traillii extimus) Overview Predicted Impacts Habitat Change 2030 48-50% Loss 2060 54-62% Loss 2090 62-71% Loss Adaptive capacity Very Low Fire Response Negative Status: The Southwestern willow flycatcher has been on the federal endangered species list since 1995. Range and Habitat: The Southwestern Willow flycatcher inhabits riparian areas in the southwestern U.S. (Figure 1). It winters in southern Mexico, Central America and northern South America (Sedgwick 2000). In the Middle Rio Grande, the Southwestern willow flycatcher migrates through willow, cottonwood and saltcedar stands (Hunter 1988; Cartron et al. 2008). It is common in New Mexico during migration in the spring and fall, but also breeds in a few areas along the Middle Rio Grande. This species is associated with dense shrubby and wet habitats and typically nests in flooded areas with willow dominated habitat (Sedgwick 2000). Generally, the Southwestern willow flycatcher does not occupy areas dominated by exotics (Skoggs and Marshall 2000), but can successfully nest in saltcedar-dominated habitats (Skoggs et al. 2006). Figure 1. Distribution of Empidonax traillii subspecies. From Sogge et al. 2010, USGS. Southwestern Willow Flycatcher (Empidonax traillii extimus) Climate Impacts and Adaptive Capacity Adaptive capacity score = 2.5 (very low) There are a number of indications for potential negative impacts for the flycatcher under changing climate (Table 1). The Southwestern willow flycatcher uses shrubs and small trees for nesting substrates. Increased shrub cover is associated with reproductive success of the Southwestern willow flycatcher (Bombay et al. 2003). Additionally, willow flycatchers will not nest if water is not flowing (Johnson et al. -

The Prosopis Juliflora - Prosopis Pallida Complex: a Monograph

DFID DFID Natural Resources Systems Programme The Prosopis juliflora - Prosopis pallida Complex: A Monograph NM Pasiecznik With contributions from P Felker, PJC Harris, LN Harsh, G Cruz JC Tewari, K Cadoret and LJ Maldonado HDRA - the organic organisation The Prosopis juliflora - Prosopis pallida Complex: A Monograph NM Pasiecznik With contributions from P Felker, PJC Harris, LN Harsh, G Cruz JC Tewari, K Cadoret and LJ Maldonado HDRA Coventry UK 2001 organic organisation i The Prosopis juliflora - Prosopis pallida Complex: A Monograph Correct citation Pasiecznik, N.M., Felker, P., Harris, P.J.C., Harsh, L.N., Cruz, G., Tewari, J.C., Cadoret, K. and Maldonado, L.J. (2001) The Prosopis juliflora - Prosopis pallida Complex: A Monograph. HDRA, Coventry, UK. pp.172. ISBN: 0 905343 30 1 Associated publications Cadoret, K., Pasiecznik, N.M. and Harris, P.J.C. (2000) The Genus Prosopis: A Reference Database (Version 1.0): CD ROM. HDRA, Coventry, UK. ISBN 0 905343 28 X. Tewari, J.C., Harris, P.J.C, Harsh, L.N., Cadoret, K. and Pasiecznik, N.M. (2000) Managing Prosopis juliflora (Vilayati babul): A Technical Manual. CAZRI, Jodhpur, India and HDRA, Coventry, UK. 96p. ISBN 0 905343 27 1. This publication is an output from a research project funded by the United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID) for the benefit of developing countries. The views expressed are not necessarily those of DFID. (R7295) Forestry Research Programme. Copies of this, and associated publications are available free to people and organisations in countries eligible for UK aid, and at cost price to others. Copyright restrictions exist on the reproduction of all or part of the monograph. -

Final Recovery Plan Southwestern Willow Flycatcher (Empidonax Traillii Extimus)

Final Recovery Plan Southwestern Willow Flycatcher (Empidonax traillii extimus) August 2002 Prepared By Southwestern Willow Flycatcher Recovery Team Technical Subgroup For Region 2 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Albuquerque, New Mexico 87103 Approved: Date: Disclaimer Recovery Plans delineate reasonable actions that are believed to be required to recover and/or protect listed species. Plans are published by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, sometimes prepared with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, State agencies, and others. Objectives will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views nor the official positions or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. They represent the official position of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service only after they have been signed by the Regional Director or Director as approved. Approved Recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery tasks. Some of the techniques outlined for recovery efforts in this plan are completely new regarding this subspecies. Therefore, the cost and time estimates are approximations. Citations This document should be cited as follows: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2002. Southwestern Willow Flycatcher Recovery Plan. Albuquerque, New Mexico. i-ix + 210 pp., Appendices A-O Additional copies may be purchased from: Fish and Wildlife Service Reference Service 5430 Governor Lane, Suite 110 Bethesda, Maryland 20814 301/492-6403 or 1-800-582-3421 i This Recovery Plan was prepared by the Southwestern Willow Flycatcher Recovery Team, Technical Subgroup: Deborah M. -

Chihuahuan Raven)

REGION 2 SENSITIVE SPECIES EVALUATION FORM Species: (Corvus cryptoleucus/Chihuahuan Raven) Criteria Rank Rationale Literature Citations • Andrews & Righter 1 A High. The Chihuahuan Raven is limited in breeding distribution to the great plains of southeastern Colorado • Kingery Distribution and extreme southwestern Kansas. • Busby & Zimmerman within R2 • Ehrlich et al. 2 C High. This species breeds from southeastern Colorado, south through western Texas, southern Arizona • National Geographic Society Distribution and New Mexico to southern Mexico. outside R2 • Andrews & Righter 3 C High. Population expansions and contractions have been documented over the past 150 years. This • Busby & Zimmerman Dispersal species is relatively mobile. They tend to move in roving flocks after the nesting season. • Kingery Capability • Andrews & Righter 4 A High. Small, relatively isolated populations are confined primarily to southeastern Colorado and • Carter et al. Abundance in southwestern Kansas. In southwestern Kansas only 12 known nest sites have been located and several of • Busby & Zimmerman R2 those are on or near the Cimarron National Grasslands. A significant percentage of the population in Colorado occurs on the Comanche National Grasslands. • Carter et al. 5 A Low. The breeding bird survey shows nearly an eight percent decline from 1966 to 1999. However the • Kingery Population amount of data is seriously lacking to provide accurate projections. One report observed a decline of 10 • Breeding Bird Survey Trend in R2 active nests in a colony to only one active nest in Colorado from 1990 to 1995. The Partners In Flight analysis shows a moderate decline for this species in R2. • Carter et al. 6 C High. -

A Case Study on the Potential of the Multipurpose Prosopis Tree

23 Underutilised crops for famine and poverty alleviation: a case study on the potential of the multipurpose Prosopis tree N.M. Pasiecznik, S.K. Choge, A.B. Rosenfeld and P.J.C. Harris In its native Latin America, the Prosopis tree (also known as Mesquite) has multiple uses as a fuel wood, timber, charcoal, animal fodder and human food. It is also highly drought-resistant, growing under conditions where little else will survive. For this reason, it has been introduced as a pioneer species into the drylands of Africa and Asia over the last two centuries as a means of reclaiming desert lands. However, the knowledge of its uses was not transferred with it, and left in an unmanaged state it has developed into a highly invasive species, where it encroaches on farm land as an impenetrable, thorny thicket. Attempts to eradicate it are proving costly and largely unsuccessful. In 2006, the problem of Prosopis was hitting the headlines on an almost weekly basis in Kenya. Yet amidst calls for its eradication, a pioneering team from the Kenya Forestry Research Institute (KEFRI) and HDRA’s International Programme set out to demonstrate its positive uses. Through a pilot training and capacity building programme in two villages in Baringo District, people living with this tree learned for the first time how to manage and use it to their benefit, both for food security and income generation. Results showed that the pods, milled to flour, would provide a crucial, nutritious food supplement in these famine-prone desert margins. The pods were also used or sold as animal fodder, with the first international order coming from South Africa by the end of the year. -

Life History Account for Lesser Nighthawk

California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Interagency Wildlife Task Group LESSER NIGHTHAWK Chordeiles acutipennis Family: CAPRIMULGIDAE Order: CAPRIMULGIFORMES Class: AVES B275 Written by: M. Green Reviewed by: L. Mewaldt Edited by: D. Winkler, R. Duke DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND SEASONALITY An uncommon summer resident in arid lowlands, primarily in desert scrub, desert succulent shrub, desert wash, and alkali desert scrub habitats. Also forages over grasslands, desert riparian, and other habitats with high densities of flying insects. Occurs north in the Sacramento Valley to Tehama Co. (Grinnell and Miller 1944) and southern Shasta Co., and to lower Mono Co. east of the Sierra Nevada (McCaskie et al. 1979). More common in desert areas of southeastern California. Casual in winter mostly in southeastern deserts. Transients sometimes noted on the Channel Islands in spring and summer, and rare in spring on Farallon Islands (DeSante and Ainley 1980). SPECIFIC HABITAT REQUIREMENTS Feeding: Feeds on insects, which it hawks on long, low flights over open areas. Also makes short flights from the ground in the manner of a common poorwill (Bent 1940). Cover: Nests and roosts on bare sand and gravel surfaces; desert floor, along washes; sometimes uses levees and dikes for nesting. Forages over grasslands, open riparian areas, agricultural lands, and similar open habitats where insects thrive. Reproduction: Nests in the open on gravelly or sandy substrate. Also uses dikes and levees for nesting. Water: May drink while skimming over water surface (Bent 1940). Pattern: Undisturbed gravel or sand surface for roosting and nesting; open lowlands, riparian areas, agricultural fields, or other insect-rich areas for foraging. -

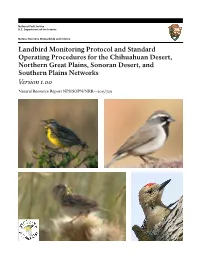

Landbird Monitoring Protocol and Standard Operating

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Landbird Monitoring Protocol and Standard Operating Procedures for the Chihuahuan Desert, Northern Great Plains, Sonoran Desert, and Southern Plains Networks Version 1.00 Natural Resource Report NPS/SOPN/NRR—2013/729 ON THE COVER Upper left: Western Meadowlark (Sturnella neglecta)1, one of the most common species for SOPN. Upper right: Black-throated Sparrow (Amphispiza bilineata)2, one of the most common species for CHDN. Lower left: Grasshopper Sparrow (Ammodramus savannarum)3, one of the most common species for NGPN. Lower right: Gila Woodpecker (Melanerpes uropygialis)2, one of the most common species for SODN. 1Photo © John and Karen Hollingsworth 2Photo © Robert Shantz 3Photographer Dan Licht - NPS. Landbird Monitoring Protocol and Standard Operating Procedures for the Chihuahuan Desert, Northern Great Plains, Sonoran Desert, and Southern Plains Networks Version 1.00 Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SOPN/NRTR—2013/729 Authors (listed alphabetically) 4National Park Service Kristen Beaupré1 Chihuahuan Desert Network Robert E. Bennetts2 New Mexico State University Jennifer A. Blakesley3 3655 Research Dr., Genesis Building D Kirsten Gallo4 Las Cruces, NM 88003 David Hanni3 Andy Hubbard1 5USGS Southwest Biological Science Center Ross Lock3 Sonoran Desert Research Station Brian F. Powell5 School of Natural Resources Heidi Sosinski2 University of Arizona Patricia Valentine-Darby6 Tucson, Arizona 85721 Chris White3 Marcia Wilson7 6University of West Florida Department of Biology 11000 University Parkway 1National Park Service Pensacola, Florida 32514 Sonoran Desert Network 7660 E. Broadway Blvd., Suite #303 7National Park Service Tucson, Arizona 85710 Northern Great Plains Network 231 East St. -

The Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Bird Conservation Plan

The Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Bird Conservation Plan A Strategy for Protecting and Managing Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Habitats and Associated Birds in California A Project of California Partners in Flight and PRBO Conservation Science The Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Bird Conservation Plan A Strategy for Protecting and Managing Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Habitats and Associated Birds in California Version 2.0 2004 Conservation Plan Authors Grant Ballard, PRBO Conservation Science Mary K. Chase, PRBO Conservation Science Tom Gardali, PRBO Conservation Science Geoffrey R. Geupel, PRBO Conservation Science Tonya Haff, PRBO Conservation Science (Currently at Museum of Natural History Collections, Environmental Studies Dept., University of CA) Aaron Holmes, PRBO Conservation Science Diana Humple, PRBO Conservation Science John C. Lovio, Naval Facilities Engineering Command, U.S. Navy (Currently at TAIC, San Diego) Mike Lynes, PRBO Conservation Science (Currently at Hastings University) Sandy Scoggin, PRBO Conservation Science (Currently at San Francisco Bay Joint Venture) Christopher Solek, Cal Poly Ponoma (Currently at UC Berkeley) Diana Stralberg, PRBO Conservation Science Species Account Authors Completed Accounts Mountain Quail - Kirsten Winter, Cleveland National Forest. Greater Roadrunner - Pete Famolaro, Sweetwater Authority Water District. Coastal Cactus Wren - Laszlo Szijj and Chris Solek, Cal Poly Pomona. Wrentit - Geoff Geupel, Grant Ballard, and Mary K. Chase, PRBO Conservation Science. Gray Vireo - Kirsten Winter, Cleveland National Forest. Black-chinned Sparrow - Kirsten Winter, Cleveland National Forest. Costa's Hummingbird (coastal) - Kirsten Winter, Cleveland National Forest. Sage Sparrow - Barbara A. Carlson, UC-Riverside Reserve System, and Mary K. Chase. California Gnatcatcher - Patrick Mock, URS Consultants (San Diego). Accounts in Progress Rufous-crowned Sparrow - Scott Morrison, The Nature Conservancy (San Diego). -

Willow Flycatcher (Empidonax Traillii) Robert B

Willow Flycatcher (Empidonax traillii) Robert B. Payne (Click to view a comparison of Atlas I to II) © Jerry Jourdan Distribution Willow Flycatchers are widespread in late Willow Flycatchers are common summer spring and summer in northeastern North residents in southern Michigan and are sparsely America and in much of the northern plains and distributed in northern Michigan. In Michigan in the west. The species was known in earlier they are generally more southern than Alder records in Michigan as "Alder Flycatcher" and Flycatchers, but the two species overlap in their "Traill's Flycatcher" (Barrows 1912, Wood breeding range throughout the SLP and NLP. 1951), and the early records did not distinguish Willow Flycatchers live in a variety of habitats between two distinct species, Willow Flycatcher of upland brush and lowland swamps, in and Alder Flycatcher. Only about 80-90% of overgrown uplands, dry marsh with unplowed birds of the two species can be distinguished in brushy grassy fields, old pasture land and morphology, but their behavior is distinct. thickets, shrubs along the edges of streams, and Willow Flycatchers give two song themes in wet thickets of willow, alder and buckthorn. In irregular alternation, "FITZ-bew!" and "FEE- southern Michigan most birds arrive from 7 to BEOO!" As they sing, Willow Flycatchers toss 17 May. The birds remain on their breeding back their heads further for the first note (in grounds from May through August and some "FITZ-bew!") or the same distance for the first birds are seen there in early September and second notes (in "FEE-BEOO!"). The (Walkinshaw 1966). -

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with Birds Observed Off-Campus During BIOL3400 Field Course

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with birds observed off-campus during BIOL3400 Field course Photo Credit: Talton Cooper Species Descriptions and Photos by students of BIOL3400 Edited by Troy A. Ladine Photo Credit: Kenneth Anding Links to Tables, Figures, and Species accounts for birds observed during May-term course or winter bird counts. Figure 1. Location of Environmental Studies Area Table. 1. Number of species and number of days observing birds during the field course from 2005 to 2016 and annual statistics. Table 2. Compilation of species observed during May 2005 - 2016 on campus and off-campus. Table 3. Number of days, by year, species have been observed on the campus of ETBU. Table 4. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during the off-campus trips. Table 5. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during a winter count of birds on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Table 6. Species observed from 1 September to 1 October 2009 on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Alphabetical Listing of Birds with authors of accounts and photographers . A Acadian Flycatcher B Anhinga B Belted Kingfisher Alder Flycatcher Bald Eagle Travis W. Sammons American Bittern Shane Kelehan Bewick's Wren Lynlea Hansen Rusty Collier Black Phoebe American Coot Leslie Fletcher Black-throated Blue Warbler Jordan Bartlett Jovana Nieto Jacob Stone American Crow Baltimore Oriole Black Vulture Zane Gruznina Pete Fitzsimmons Jeremy Alexander Darius Roberts George Plumlee Blair Brown Rachel Hastie Janae Wineland Brent Lewis American Goldfinch Barn Swallow Keely Schlabs Kathleen Santanello Katy Gifford Black-and-white Warbler Matthew Armendarez Jordan Brewer Sheridan A. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Zootaxa, a New Genus for Three Species of Tyrant Flycatchers (Passeriformes: Tyrannidae)

Zootaxa 2290: 36–40 (2009) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2009 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) A new genus for three species of tyrant flycatchers (Passeriformes: Tyrannidae), formerly placed in Myiophobus JAN I. OHLSON1, JON FJELDSÅ2 & PER G. P. ERICSON3 1) Department of Vertebrate Zoology, Swedish Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 50007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden. Email: [email protected] 2) Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen, Universitetsparken 15, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark. Email: [email protected] 3) Director of Science, Swedish Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 50007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden. Email: [email protected] Abstract A new genus, Nephelomyias, is erected for three species of Andean tyrant flycatchers (Aves: Passeriformes: Tyrannidae) traditionally placed in the genus Myiophobus. An extensive study based on molecular data has shown that they form a well supported clade that is not closely related to other Myiophobus species. Instead, they form a small independent lineage in Tyrannidae, together with Pyrrhomyias, Hirundinea and Myiotriccus. Key words: Nephelomyias lintoni, Nephelomyias ochraceiventris, Nephelomyias pulcher, Tyrannidae, taxonomy, phylogeny Introduction Recent phylogenetic studies, based on extensive molecular data (e.g. Ohlson et al. 2008; Tello et al. 2009), have greatly improved our knowledge of the relationships and evolution of the tyrant flycatchers (Tyrannidae). Several unexpected relationships have been revealed and a number of traditional genera have proven to be non-monophyletic, prompting taxonomic rearrangements. Here we erect a new generic name for three species traditionally placed in the genus Myiophobus, which were found by Ohlson et al.